The Greenbelt: Finding a Balance

The greenbelt is only one part of a gutsy and massive initiative by Dalton McGuinty’s new Liberal govern-ment to overhaul land-use planning in the province.

A proposed greenbelt through Caledon is part of a massive overhaul of provincial land-use policies. The goal is to curb urban sprawl and protect farmland and the environment. What does it mean for our hills?

The Metcalfes have an impressive farm southeast of Inglewood. From their elegant heritage home, 49-year-old Joe, his wife, Liz, their son and two daughters gaze out over lush and orderly corn and soybean fields on the Peel Plain. It’s the land Joe’s father farmed before him. Asked if he’d sell it to a developer, Joe responds, “In a heartbeat.”

When he was young, recalls a frustrated Joe, there were dozens of kids ready to “step up to the plate” and take over the family farm. “Now,” he says, “there’s only one or two.”

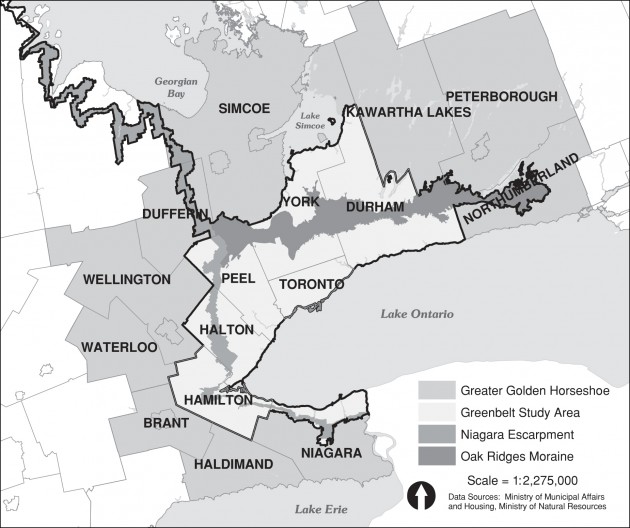

Joe Metcalfe is one of many local farmers who oppose the provincial government’s efforts to create a greenbelt in southern Ontario. The proposed legislation would restrict development on agricultural and environmentally significant lands in Peel, York, Durham, Halton, Toronto and Hamilton, as well as the Niagara Escarpment and Oak Ridges Moraine plan areas, and Niagara’s tender fruit and grape lands. In Dufferin, only the Niagara Escarpment area is affected. Erin falls outside the study boundaries.

John Gerretsen, minister of municipal affairs and housing, says the government’s goal is to “put the brakes on runaway urban sprawl.”

The government predicts the population of Central Ontario, which stood at 7.5 million in 2001, could swell by another four million by 2031. And, according to the discussion paper of the greenbelt task force, “Studies have shown that if current trends persist, in the next 30 years … development will consume another 1,069 square kilometres of mainly prime agricultural land, an area nearly twice the size of the City of Toronto.”

Both British Columbia and Quebec have legislation that strictly limits what can be done with prime agricultural land. In Ontario, however, agriculture is still a relatively unregulated land use (residential and industrial lands, even aggregate resource lands, are subject to stricter regulations). In response to resistance from the agricultural community, successive governments have settled for “guidelines” rather than legislation in their agricultural planning policies.

In its response to the Greenbelt Task Force Discussion Paper, the Ontario Federation of Agriculture expressed concerns that the proposed greenbelt could “destroy the economic viability of farmers in the Greenbelt area.” The OFA suggested the legislation could take away farmer equity, increase trespass by the public and predation by wildlife, and put more cars on the roads by encouraging leapfrog development into areas beyond the greenbelt.

Several local farmers expressed a much more visceral response at a heated public meeting in Caledon East in May, accusing the government of expropriation without compensation.

Caledon councillor Nancy Stewart, whose family has been farming in Caledon for 150 years, is one of those who is “not delighted” with the greenbelt proposal. “Aging farmers need to cash out their pension plans,” she argues. “They must sell their farms.” Because family members can’t or won’t buy them, she says farmers need the option to sell out to developers. She adds, “We should be helping the farmers get the hell out of it and get their money.”

Few would argue that Canadian agriculture doesn’t have problems. According to a recent Statistics Canada report, farm incomes are at their lowest level in 25 years. But for many, allowing farmers on the urban fringe to cash in on inflated real estate prices isn’t the best way to deal with the industry’s chronic woes. But, or so Caledon mayor Marolyn Morrison argues, neither is freezing agricultural land.

Councillor Stewart says she’s not worried about losing agricultural land in Caledon, “because with increased productivity and the low cost of food we can grow it elsewhere.” But Mayor Morrison has another idea. She explains, “I’ve been saying to the minister of municipal affairs that if they would just look at Caledon’s policies and look at how we have protected our land and look at the flexibility that will let farmers survive, they could use them.”

Caledon’s new agricultural area and rural area policies permit diversification of on-farm income, within limits. Caledon now encourages on-farm enterprises such as Bailey’s Country Market on King Street, and Broadway Market and Downey’s Farm Market on busy Heart Lake Road. (Downey’s has extended the farm market idea into a kind of farm theme park that features farm-related rides, games and special events.) Farmers in Caledon who need extra income can now earn it without necessarily having to leave the farm. However, the town does not permit amusement parks and rendering plants in prime agricultural areas.

Anne Livingston is a good example. Her sons run the family farm on Heart Lake Road. “I wasn’t born a farmer, but I like the life,” says Anne. “The thing that I would hate is to see all the farmers get out. I don’t want to become part of Brampton.”

But Anne knew that if farming was to survive in Caledon, things had to change. So, a few years ago her family tore down their milking parlour and built Broadway Market. It sells meat, cheese and other farm products. She admits, “The market made more money in July than all the rest of the farming that we do.”

Anne, who ran Marolyn Morrison’s successful election campaign last November, praises Caledon’s municipal government for its efforts to give agriculture a future.

Municipal policies in Caledon are helping less traditional farmers too. The area around The Grange and Creditview Road was recently designated an equestrian neighbourhood, complete with special signage and promises of reduced road speeds. Residents with horse farms in the area pitched the idea to council in order to keep their roads horse-friendly by exempting them from paving.

A recent report by the Dufferin-Caledon Life Science Innovation Team, sponsored by the ministry of municipal affairs, further examines the idea of mixing agriculture and commerce. One of the report’s 18 recommendations suggests Caledon should establish an equine business park that provides office space for horse-industry trade associations and related equine businesses. Another recommends building an ethanol plant near Shelburne that would use culled potatoes as its raw material, and a third describes the designation of organic production zones in Mono.

Perhaps more controversially, the report also suggests the region could be prime territory for developing opportunities in biotechnology and “molecular farming” – the report describes the latter as a way of making pharmaceuticals by introducing foreign genes into agricultural organisms, such as livestock and crops. Noting that some people have “strong, emotionally charged opinions” about such industries, the report warns that the municipalities would require good policing, security and fire protection services.

Opening up the countryside for business, as Caledon is doing and the life science report recommends, is an experiment. Until Caledon passed its agricultural polices last year, many rural enterprises were technically illegal.

Some fear that these business options could be taken away by the government’s greenbelt proposal. In its response to the greenbelt task force, Caledon said, “The Paper proposes protecting agricultural lands by restricting severance activity. Uses would also be limited to secondary agriculture, and agricultural-related uses are directed to settlement areas.” This “has the unfortunate effect of severely limiting the use of these lands and also the farmer’s viability.”

Rob Brindley, Caledon’s director of economic development, observes, “We don’t disagree with the intent of the greenbelt legislation. We’re already doing it. But the details don’t back up the intent.” He fears that under it, “all those subtle ways of economic development, like small B&Bs or Downey’s or many of the recommendations in the life sciences report, would not be allowed.”

Admittedly, getting all the details right won’t be easy. The greenbelt is only one part of a gutsy and massive initiative by Dalton McGuinty’s new Liberal government to overhaul land-use planning in the province.

With its “Grand Plan,” as the far-reaching initiatives might be dubbed, the provincial government is simultaneously:

- Reviewing and aligning the Provincial Policy Statement, the Ontario Municipal Board and the Planning Act

- Developing policies that will govern transportation and infrastructure

- Coming up with a separate plan for rural communities

- Asking municipalities to implement watershed-based source-protection plans and farmers to switch to new nutrient (manure) management plans to ensure clean drinking water

- Introducing Bill 60, the proposed Ontario Heritage Amendment Act, that will give the province and municipalities new powers to stop the demolition of heritage sites

- Designating urban areas where growth, preferably compact growth, will occur.

If the government gets the details right – and that’s a big if – the Grand Plan could reduce the number of times infrastructure policy conflicts with environmental legislation. It could prevent the Ontario Municipal Board from overruling municipal official plans that comply with the Provincial Policy Statement. And it could preserve agricultural land without bankrupting the farming community.

Glen Schnarr, a developer who spends a fair bit of time working in Caledon, compliments the town’s efforts: “I think Caledon has done an enviable job of staying green while respecting the rights of farmers and industrial landowners who have certain expectations.” But he’s dead set against the greenbelt legislation.

“I can see how the farmers could and should be justifiably bitter. I would also be bitter if I were a landowner who made an investment in land where certain uses are permitted in the official plan and the province comes along and says here’s the zoning order and nothing is permitted anymore.”

David Douglas, a professor in the University of Guelph’s School of Rural Planning, suggests that some of the farmers’ concerns might be resolved if Ontario adopted a European model of paying “environmental premiums.” These are paid to farmers who maintain “heritage landscapes,” by preserving wetlands and hedgerows, and for other forms of environmental protection, such as limiting or eliminating pesticide use. In some cases, he says, the premiums represent as much as 20 to 40 per cent of farm income. In Canada, he says, “We’re not debating [environmental premiums] yet, but we’re close.”

In fact, a similar idea was put forward by the Christian Farmers’ Federation of Ontario in its response to the proposed greenbelt. The federation recommends the creation of “a stewardship classification for lands in the urban shadow for assessment purposes. Landowners who engage in maintaining their lands so they contribute to clean water, fresh air and beautiful vistas should have their own classification and pay a lower level of property tax than farmland.” Recognizing the corresponding loss to municipal tax revenue, the federation adds, “A provincial rebate of the property taxes would be even better.”

Another possible means of compensating farmers for protecting their land is mentioned in the Greenbelt Consultation Paper. It involves use of easements. The newly launched Ontario Farmland Trust explains that easements are legal agreements that are permanently attached to land titles. While the farmer maintains ownership of the land, he or she sells or donates the development rights to an agency such as the Ontario Farmland Trust. In this way, farmers can continue to farm and be compensated financially for giving up the right to sell their property to, for example, a developer. Easements are regularly used to protect ecologically sensitive land in Canada, however, because there is no corresponding legal mechanism for farms, they are not currently an option for agricultural land. This would require changes to federal income tax laws, something the Ontario Farmland Trust is pursuing.

The effects of a greenbelt, though, would not be limited to farmers. Nor would a greenbelt only have an impact on the municipalities that fall within its boundaries. Communities next to the greenbelt could well fall victim to “leapfrog development,” as developers and home buyers jump over the greenbelt to the next closest community.

Orangeville mayor Drew Brown says the town is “concerned about being right on the border of the greenbelt. We’re worried about the growth pressure it will put on us.” He doesn’t think Orangeville should grow too big or too quickly. He’s convinced the majority of residents don’t want this small city of 26,800 to grow too fast, or to expand beyond its built-out population of 33,000.

In the mayor’s opinion, development in surrounding municipalities already puts tremendous strain on Orangeville’s services because non-residents expect to have access to facilities even though they are paid for by Orangeville tax-payers. “They think of themselves as living in Orangeville,” says Mayor Brown. “There-fore, there is a tremendous reaction when we attempt to implement a surcharge.” The town, for instance, is still dealing with angry fallout from its recent decision to charge non-residents a hefty annual fee of $145 for use of the town library.

Orangeville falls within Dufferin County and Mayor Brown faults the county’s lack of planning for the town’s woes. Dufferin is one of only two counties in Ontario that doesn’t have an official plan or a planning department. By contrast, although Caledon and Dufferin have roughly the same population, Caledon employs more than 30 people in its planning and development department. Among the eight lower-tier municipalities in Dufferin, only three employ planning staff: four in Orangeville, two in Mono and a part-timer in Shelburne.

In another of its Grand Plan consultation papers, Growing Strong Rural Communities, the province suggests that one way to improve “municipal fiscal capacity” in small towns is to encourage partnerships among municipalities to capitalize on economies of scale.

John Fitzgibbon, the director of the School of Rural Planning at the University of Guelph, concurs. He believes that service sharing is the way to go and that amalgamation may be the way to get there.

Amalgamation, though, is likely to be anathema to communities in Dufferin where wounds are not fully healed from the bitter struggle against the former Conservative government’s pressure to dissolve interior borders. Further south, Mississauga mayor Hazel McCallion says the Region of Peel, once the poster-child for amalgamation, has outlived its purpose. Over Caledon’s objections, she vigorously attempted to remove Mississauga from the region.

“I never did support the idea of forced amalgamation,” says Orangeville’s Drew Brown. In fact, he won office in large part because of his opposition to it. Still, he says, some form of service sharing makes sense. “It’s incumbent on us to sit down and discuss the possibilities… That silly little line [a municipal border] presents a huge barrier to sensible planning.”

Ideally, both the greenbelt and rural community policies should complement proposed amendments to the Provincial Policy Statement. The PPS outlines overall policy direction on land-use planning and development in the province. The review of the PPS began under the Conservative government in 2001 with a series of public consultation meetings and a promise to implement changes that follow the principles of Smart Growth – a planning strategy that originated in the United States and focusses on compact urban development and environmental protection.

Long-time Caledon resident and environmentalist Debbe Crandall applauds the spirit of the proposed PPS amendments, but notes, “The policies don’t bear out the good intentions seen in the preamble.” For instance, although the government was advised to allow for regional variability, the PPS fails to recognize local and regionally significant natural heritage features, only protecting provincially significant ones.

Bill Wilson, a member of Caledon’s environmental advisory committee, adds his pet peeve. The introduction to the natural heritage section of the PPS stresses the importance of protecting the ecological function of “natural heritage systems.” However, in the details, rather than describe how “systems,” such as whole watersheds, can be protected, the PPS simply lists types of landscapes, such as wetlands or woodlands, that are exempt from development.

Despite concerns about the PPS, the environmental community generally favours the concept of a greenbelt. Ontario Nature (formerly the Federation of Ontario Naturalists) believes that the greenbelt, as it was described in the discussion paper, would give the province “the building blocks for creating a permanent continuous system of protected core natural areas, linked by natural corridors, with the Niagara Escarpment and the Oak Ridges Moraine as its anchors…”

Nancy Stewart is more sceptical of the government’s agenda. She quips, “Ontario’s most recent experience with a greenbelt is now Highway 407.” And she has a point. In Places to Grow, another building block in the Grand Plan, the government sets out its growth-management strategies for urban regions within the Greater Golden Horseshoe. Although it states that the greenbelt “should not be viewed as a land reserve for future infrastructure needs,” it points out that gridlock in the GTA is expected to increase by 45 per cent over the next 30 years. Furthermore, a map in the report shows a swath across Caledon’s prime agricultural land that is marked as an “economic corridor.”

Hazel McCallion’s Central Ontario Smart Growth Panel coined the phrase “economic corridor” and defined it as a “transportation corridor” that links an outlying region with an economic centre. Could this be doublespeak for a 400 series highway connecting the GTA with Waterloo and Kitchener, both priority urban centres, as well as Guelph, an emerging one as designated in Places to Grow?

Other sceptics argue that greenbelt development controls will depress land prices. It was the same argument made when the government introduced the Niagara Escarpment plan in 1973. A pair of studies, however, shows the opposite effect. A 1980 report found there was no negative impact on real estate values for agricultural, estate-residential or recreational properties in the Niagara Escarpment plan areas in Dufferin, Grey or Simcoe counties. A new study, released in 2003, discovered that Dufferin lots inside the plan area actually sold for prices that were 8 to 32 per cent higher than comparative properties outside the plan boundaries.

The findings would be no surprise to developer Glen Schnarr, but they wouldn’t put him at ease either. In fact, he fears the greenbelt will cause housing prices in Caledon to “skyrocket.”

Within the Grand Plan there is one small wording change, in particular, that will arguably have as profound an effect on municipal planning, and municipal coffers, as anything else the government is proposing. Mike Harris’s Conservative government amended the Provincial Policy Statement and the Planning Act to require that planning decisions made under the Act merely “have regard for” rather than “be consistent with” the principles set out in the Provincial Policy Statement. The move opened legal wiggle room for defining just how much “regard” was enough, and prompted Mark Dorfman, then president of the Federation of Ontario Naturalists, to declare, “The province has gotten out of the planning business.”

The result was that the Ontario Municipal Board, the independent tribunal that hears appeals on planning decisions, often overturned municipal decisions in favour of developers, effectively substituting its decisions for those of elected councils.

To ensure provincial interests are entrenched in land-use decisions, the Liberals propose to restore the more prescriptive direction that planning decisions must “be consistent with” the Provincial Policy Statement. Add this to the government’s promise that it will limit appeals to the OMB on applications to expand urban boundaries or establish new urban settlements, and municipalities can expect to spend less time defending their decisions in costly OMB hearings.

Work on the greenbelt and the other planning documents began soon after the Liberal government was elected last winter. With the exception of Places to Grow, the opportunity to submit comments on all the initiatives in the Grand Plan has already passed. Bureaucrats and legislators in Queen’s Park will continue to work on elements of the Grand Plan throughout the fall. In the winter, Ontario can expect to see final legislation and policies released, discussed and, presumably, passed into law.