Places to Grow turns 10

The Growth Plan was an attempt to rein in the low-density sprawl that was a signature of development in the 1980s and 1990s.

Childhood of a Galactic Metropolis

As Places to Grow turns 10, the Neptis Foundation checks in with some disturbing questions.

Geographer Peirce Lewis coined the term “galactic metropolis” to define a region with a number of developing edge nodes, where urban centres are widely dispersed like stars, often without a single, obvious core or centre.

In a nutshell, that’s what the Ontario government was aiming for in 2006, when it released Places to Grow: Growth Plan for the Greater Golden Horseshoe, a framework for handling development over the next 25 years.

The Growth Plan

The Growth Plan was an attempt to rein in the low-density sprawl that was a signature of development in the 1980s and 1990s. It sets out policies governing infrastructure and the environment, as well as where and how development can occur. Most notably, it establishes population and employment growth projections, and allocates this growth chunk by chunk to the 21 upper- and single-tier municipalities in the Greater Golden Horseshoe.

The numbers are eye-popping. The original projections in Places to Grow suggested the population of the Greater Golden Horseshoe would swell to 11.5 million in 2031 from 8.1 million in 2006, an increase of 3.4 million. Then, in 2013, the province extended the planning horizon by a decade to 2041 and added 2 million people, bringing the current projected total to 13.5 million.

This amounts to building a city bigger than Oshawa every year for 35 years. Put another way, it means more than 420 new people – the student body of an average elementary school – must be housed and fed, and kept healthy, educated and employed every single day for the next three and a half decades.

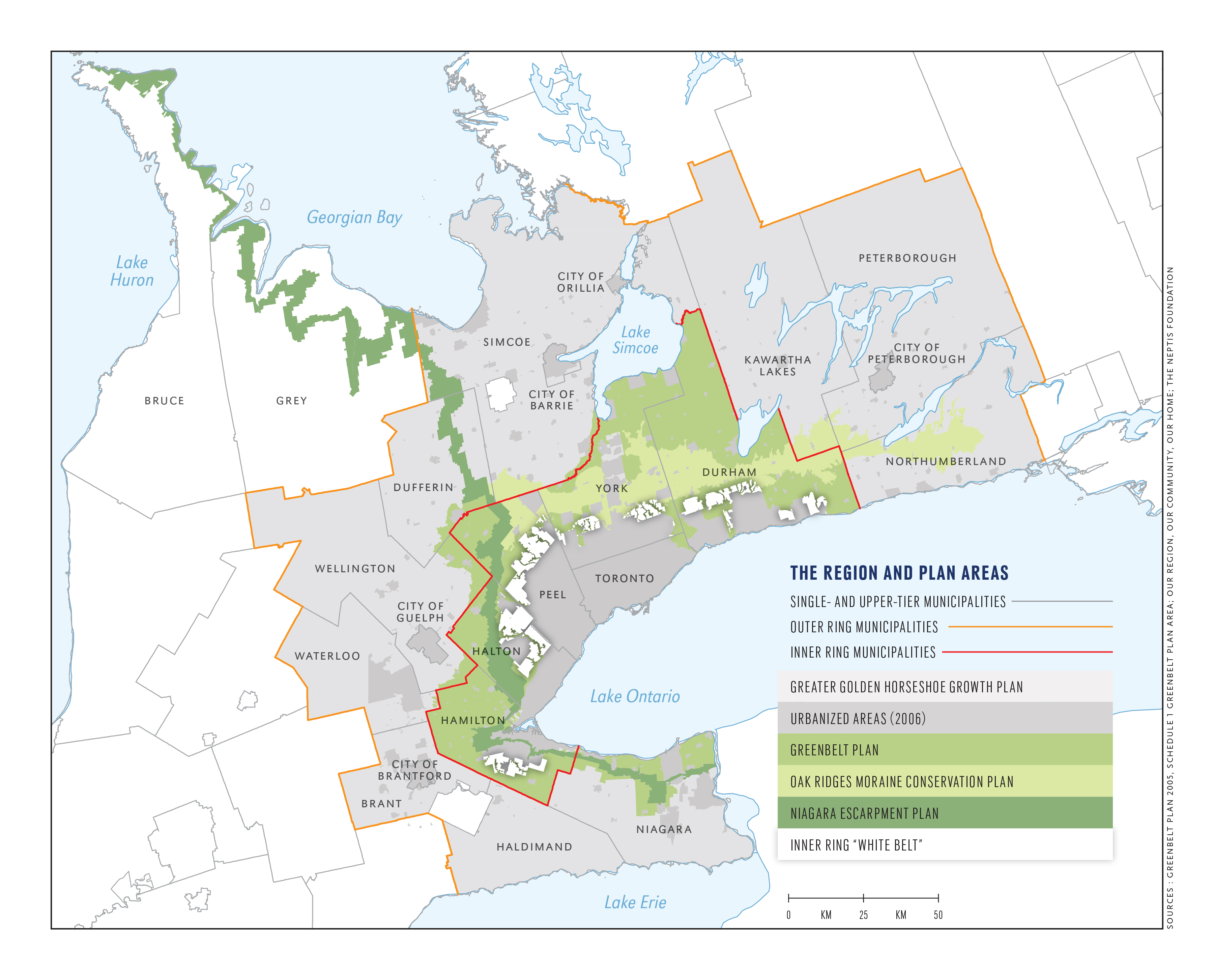

Though Places to Grow speaks to growth, it was developed to work in concert with the Niagara Escarpment Plan, the Oak Ridges Moraine Conservation Plan, and the Greenbelt Plan, which deal with conservation. Places to Grow and the Greenbelt Plan are now approaching their 10th anniversaries, the point at which both are slated for significant review. As a result, the province announced the Co-ordinated Land Use Planning Review, which will look at all four plans over the course of 2015 and make recommendations.

With an advisory panel chaired by former federal cabinet minister and Toronto mayor David Crombie, the review has gathered input at public meetings across the region. A second round of meetings will take place in the fall, when draft changes will be presented.

The Neptis Foundation is a Toronto think tank that focuses specifically on growth. The privately capitalized charitable organization conducts and disseminates nonpartisan research, analysis and mapping related to the design and function of Canadian urban regions.

Neptis participated extensively in the initial development of both Places to Grow and the Greenbelt Plan, so the foundation’s perspective is particularly valuable to the 10-year review. In March this year, the group released a discussion paper titled Understanding the Fundamentals of the Growth Plan. It examines the challenges and opportunities for improvement as Places to Grow enters its second decade.

The document raises some disturbing questions about the effectiveness of Places to Grow. In particular, it notes the scope for creative interpretation and rule-bending at the municipal level that undermines the grand plan to stem sprawl.

But first, Neptis executive director Marcy Burchfield stresses it’s important to place these concerns in context: “The Growth Plan was really the first approach to growth management for the Greater Golden Horseshoe, a very large, very fast-growing region. Prior to the Growth Plan, all municipalities were doing their own thing, often in isolation. So the real success is just having the Growth Plan to begin with, so that there are a set of rules and an approach and a framework for a broad regional vision.

“One of the primary things to get across is that it’s a good thing to have the Growth Plan.”

Although the plan’s concept is commendable, Burchfield says, “the point of the Neptis report was to take the reader through where the Growth Plan had its challenges, and those are truly in the implementation. Even though there was this wide regional vision … everything went back down to the municipalities in terms of allocating the population and employment projections. The upper-tier municipalities were responsible for allocating that growth across their lower-tier municipalities and in doing so, there was judgement within the municipality, but not necessarily in consideration of the Greater Golden Horseshoe as a whole, of who gets how much where.”

The Region and Area Plans. Click to view larger image. Sources: Greenbelt Plan 2005, Schedule 1 Greenbelt plan area; Our region, Our community, Our home; The Neptis Foundation

A few hundred houses

for you, an industrial

park for you.

And you

get an expressway!

Places to Grow employs two main levers to control sprawl. The first is intensification. The plan requires at least 40 per cent of all residential development occurs within areas that were already urbanized in 2006.

The second lever is density. New development lands, often known as “greenfield” lands, must accommodate a combined total of at least 50 residents and jobs per hectare, averaged over each single- or upper-tier municipality.

Though the province established these broad goals, municipalities were not provided with any clear rules on how to achieve them. Burchfield says, “There’s always this tension between local autonomy and the big, heavy hand of the province, but when you have a plan for the whole Greater Golden Horseshoe, there needs to be a bit more direction to matching future growth to where the infrastructure is. Lack of guidelines in the implementation of the plan led to all sorts of problems.”

Using a planning tool known as land budgeting, planners in each municipality made a variety of assumptions that have a dramatic impact on the amount of land finally set aside for urbanization.

As an example, Neptis researchers point out that Halton and York regions set aside land on the assumption that demand for single-family homes would remain strong. Waterloo, meanwhile, forecast greater demand for medium- and high-density housing, assuming that, as baby-boomer owners age and downsize, much of the demand for single-family homes would be met by existing units.

In Halton and York this meant slating large tracts of land for development, while in Waterloo, the amount was relatively little. Yet all three will accommodate their population targets. (It’s worth noting that developers took Waterloo Region to the Ontario Municipal Board over the issue and won. The decision is currently under appeal.)

The alchemy of figuring out how much land is enough is critical because billions of dollars must be invested in infrastructure – and these investments are made based on getting the projections right. In addition, municipal budgets rely heavily on property taxes. If estimates don’t materialize or there’s a big shift in the economy, projections for future municipal revenues could be off by miles.

The rule directing 40 per cent of all new residential development to already urbanized areas is itself problematic. Both Neptis and Gord Miller, Ontario’s former environmental commissioner, have pointed out that nine of the 15 outer-ring municipalities – those outside the Greenbelt – have received exemptions from the intensification target. In Brant County, the target was lowered to just 15 per cent. Peel Region proposes to exceed the target, gradually increasing to 50 per cent by 2026.

As for greenfield development, the plan’s fungible requirement for a combined average density of 50 people and jobs per hectare is ill-defined. For starters, adding jobs to the mix makes the whole thing a wild guess at best, because very little is known about existing employment densities or how these will change if Ontario’s economy continues to shift from manufacturing to a more knowledge-based economy. And just as with the intensification targets, several outer-ring municipalities have been granted lower average densities. Though Peel plans to meet the target, Dufferin’s was lowered to 44 combined people and jobs per hectare.

“We could find no hard evidence as to why these municipalities got lower targets,” says Burchfield. “There was just a request and the request was granted, essentially.” She adds, “Lowering the intensification and density targets while leaving the population forecasts unchanged results in using more land to accommodate the same number of people.”

Going for takeout

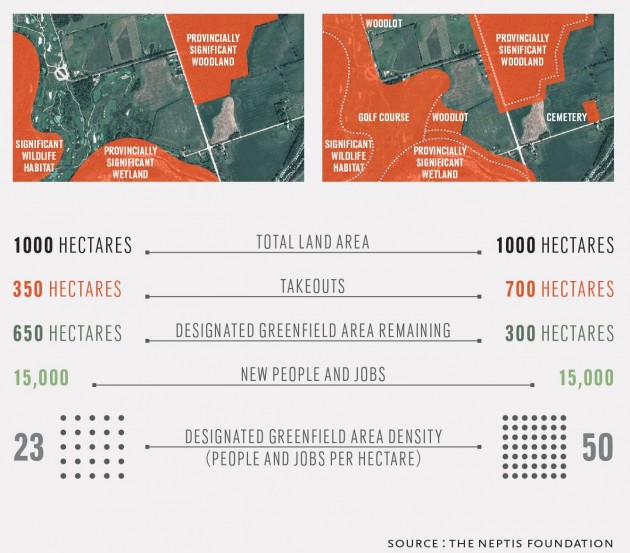

Neptis researchers also demonstrate how density targets are easily manipulated through what are known as “takeouts.”

The Growth Plan allows environmentally sensitive land – wetlands, woodlands, valleys and the like – to be taken out of land budget calculations. But each municipality made its own assumptions about what land was unavailable for development. Some included things like road and hydro corridors, golf courses and cemeteries; others didn’t. Some drew generous boundaries around features, while others were more precise.

Though all this may sound like an administrative detail or mapping exercise, takeouts throw the whole notion of calculating density into doubt.

The greater the area of takeouts, the higher the density of people and jobs per hectare a municipality can claim. Using one method, Neptis researchers calculated a combined density of 23 people and jobs per hectare. Using another method results in a combined total of more than 50 people. Yet in both cases, the same number of people occupy the same amount of land – only the way density is calculated has changed. (See graphic, below.)

The impact of takeouts on greenfield density

Municipalities that exclude – “take out” – more land from the density calculation (below right) may appear to meet the density target while developing greenfields at lower densities than municipalities that exclude only the areas and features specified in the Growth Plan (below left).

The impact of takeouts on greenfield density. Click to view larger image. Source : The Neptis Foundation

The back fifty

Examining the official plans of municipalities across the Greater Golden Horseshoe, Neptis calculates that about 107,000 hectares (1,071 square kilometres) have been designated for future development in this area. By way of comparison, the current city of Toronto measures about 63,000 hectares (630 square kilometres).

About 88,000 of those 107,000 hectares had been designated for development before the Growth Plan came into existence, with the remainder added as part of the land budgeting process. Nearly half (50,900 hectares) lies in the outer ring. But because of the lowered targets, outer-ring municipalities are expected to attract only one-third as many new people and only one-quarter as many jobs as inner-ring municipalities.

Many outer-ring municipalities offer little in the way of public transit or municipal infrastructure such as sewers, and the reduced outer-ring density and intensification targets make provision of that infrastructure impractical. This suggests the type of development that takes place in the outer ring is likely to be exactly the sort of low-density, car-oriented sprawl the Growth Plan was intended to prevent.

“There’s still an over-allocation or an over-designation of land out there, given the number of people who will be accommodated,” says Burchfield.

Tick… tock… tick… tock…

There are few places where the gears move more slowly than land development, and stretches of more than a decade between urban designation and ultimate development are common. Even if a municipality designates land, many official plans are appealed to the Ontario Municipal Board, where they can sit in limbo for years.

Though Dufferin, Peel and Wellington have put in place Growth Plan provisions (Dufferin had to create its first official plan to do this), Neptis research points out that even a decade after Places to Grow was enacted, there are still many municipalities where the Growth Plan is not yet in effect.

In the meantime, local planning decisions in those places must be made based on outdated official plans. Because most of these old plans set maximum densities, not minimum, nothing stops developers from downzoning projects – going from apartment blocks to townhomes, for example – further eroding progress on increasing density.

S-t-r-e-t-c-h-i-n-g it out

Though the volume of land designated for development seems huge, perhaps the more relevant concern is how long it will last.

Data show how much inner-ring land was developed between 2006 and 2011, but figures are not yet available for the outer ring.

Neptis calculates that about 5,200 hectares, or about 9 per cent, of the 56,200 hectares designated for development within the inner ring, were built on during this period.

Places to Grow was envisioned as a response to the development trends of the 1980s and 1990s, but those trends were changing. Neptis research demonstrates that the rate at which new land was being consumed began slowing down after 2001, five years before Places to Grow came into effect. If developers were already creating more compact communities before the Growth Plan, Neptis says, “This finding raises questions about whether the Growth Plan could have been more ambitious with its targets for intensification and new development on greenfields.”

Though the rate of land consumption may be declining, the composition of housing stock is not changing along with it. Even if developments are more compact and lot sizes smaller, the single-family detached dwelling remains king. But there is significant demand for more affordable accommodation, usually found in higher density development such as townhomes and midrise apartments.

As Neptis points out, by building affordable smaller units, municipalities might be able to kill two birds with one stone: make the land supply last longer and increase affordability.

Neptis research from 2013 concluded that “in fact, sufficient land has been set aside to accommodate population and employment at average densities similar to those that are typical today.”

So it appears that if municipalities carry on business more or less as usual, there’s room for everyone until at least 2031 – even while most municipalities adopted intensification and density targets that were either at or below the minimum. If that were to change, the current land supply would last even longer, helping to accommodate at least some of the additional two million people forecast to swell the population in the decade after 2031.

For the record

“Another real challenge in understanding the success of the plan is that there was no framework for monitoring how the policies were being implemented along the way,” says Burchfield. “So you have no indication of whether your plan is working or not.”

Even though the plan has been in place for a decade, much of the data the province presents in the documentation for the 10-year review is baseline, so there are few comparisons to be made.

“If you go to other jurisdictions,” says Burchfield, “that baseline information is one of the key things they collect at the very beginning of the implementation of a plan, or even prior to a plan, so that you can benchmark how your plan is doing along the way. In some cases, maybe policies have to be tweaked or changed completely because they’re not working. But if you haven’t measured, you’re not going to know.”

Hit the road, Jack

Another wrinkle in implementing the Growth Plan came in 2008, when the province released its regional transportation plan called The Big Move.

The Big Move sets out a long-term framework for developing the transportation network in the Greater Toronto and Hamilton Area. It’s supported by $11.5 billion in committed funding and calls for a total of $50 billion in funding over 25 years. Among other things, the funds will go toward building and upgrading roads, as well as 1,200 kilometres of new rapid transit – more than triple what now exists – so eventually more than 80 per cent of residents of the GTHA will live within two kilometres of rapid transit.

The problem is that the transportation plan didn’t exist when Places to Grow was developed, so the Growth Plan makes no attempt to direct development toward planned transit and transportation routes. As Burchfield says, “It needs to be aligned with The Big Move.”

Dad, can I borrow the car?

As our galactic metropolis heads into its tumultuous teen years, it is experiencing its share of gawky inco-ordination, the acne of strip malls, and some unfortunate fashion choices in the latest architectural trends. But the plan has also begun to show signs of maturity and achieved some goals.

“The biggest success would be that the Growth Plan has cemented in people’s minds – the planners’ minds, and in municipal politicians’ minds as well – that we need to plan at the broad regional level,” says Burchfield.

“Also, 80 per cent of the land designated for urbanization was already designated before the Growth Plan. Only 20 per cent more was added to that. So at least it stopped that process of over-designation of land. Or if not stopped it, kept it in check. I think that’s a success in its own right.”

Where will it end?

When residents of these hills talk about population growth, one question comes up again and again: When does it stop?

The short answer? Maybe never.

The United Nations estimates humanity expands by about 75 million people a year. The world’s population ticked past 7 billion in 2011 and is expected to peak at 10.1 billion in 2100.

It’s probably not possible to build a wall around the Greater Golden Horseshoe to keep the world at bay, but even if it were, the theory is that Canada needs immigration and young workers to support the social services, health care and pensions of the aging population.

So, as Burchfield says, “The Greater Golden Horseshoe has been adding about 100,000 people every year for the last 15 or 20 years. That’s just the reality. To have a plan in place to accommodate that growth in a way that makes sense is extremely important. If the growth doesn’t come … well, the growth doesn’t come. But this is a very attractive region … It’s a historical fact that this is a region people want to come to, to immigrate and settle here. The best thing we can do is plan for that.”

Achieving the vision of the growth plan in Orangeville

Nancy Tuckett, Orangeville’s director of economic development, planning and innovation, has a front-row seat on how Places to Grow is playing out in the real world.

Tuckett took over as head of planning in Orangeville two years ago, after a long career in rapidly developing Simcoe County. She believes Orangeville is developing into a good example of the sort of urban centre the Growth Plan envisions. “I think it works in Orangeville,” Tuckett says. “This community is very much a mixed-use, livable, workable, walkable community. Whether that’s a result of the Growth Plan, or it happened on its own, I think it has really worked. On my lunch hour, I can walk from the town hall to almost anywhere in town and back again. That’s a walkable community.”

Right now, Orangeville’s population is about 29,000. Surrounded by the Greenbelt, the town is hemmed in and can only grow so much. The projected built-out population is currently 36,490.

Orangeville’s planning department has long been working to accommodate growth, and Tuckett says, “A lot had been done developing policies for the official plan, to set the stage for where intensification should happen, and also looking at the greenfield areas [developable land within the town limit, but beyond the current built boundary], and where that development can occur. I think we’re seeing the effects of it now.”

Dufferin County will meet Growth Plan requirements that upper-tier municipalities achieve an intensification target of 40 per cent of new development within existing built urban boundaries, averaged over the county. With an intensification target of 50 per cent, Orangeville is expected to exceed that. Orangeville’s density target, which sets the number of people and jobs combined per hectare on greenfield development, will come in at 46, slightly less than the provincial requirement of 50 but still the highest in the county. Combined, the two factors mean Orangeville is taking some of the development pressure off the rural municipalities.

Echoing findings of the Neptis Foundation, Tuckett says trends have changed since the days when developers focused nearly exclusively on building single-family detached homes in town. Pointing to 150 new townhouses approved since she was appointed, and a stack of applications for more townhouses and condo units in the works, she says, “We’ve seen mostly medium-density development.”

Like other communities identified by Neptis, Orangeville has also struggled with implementation issues stemming from the Growth Plan. Part of Island Lake Conservation Area is within the town’s urban settlement area, but it is outside the “built boundary,” which means that land counts toward Orangeville’s greenfield area calculation. Tuckett, however, calls this area “a false greenfield” because it can never be developed. If it were not included in the calculations, Orangeville’s density would be even higher.

And there are other snags. Other parts of the greenfield area are now built out. Orangeville’s downtown is a heritage conservation district, so knocking down a few old buildings to put up a five- or six-storey apartment block isn’t an option. And, says Tuckett, “Orangeville doesn’t really have much brownfield land [sites that have had a previous use but are ripe for redevelopment].” So calculating and achieving density and intensification are tricky.

The town will also undertake a five-year review of its official plan this year. As part of this review, it will examine its employment and residential land needs to determine how best to develop its ultimate settlement area boundary.

Tuckett also calls for better guidelines from the province, in particular minimum standards for employment density. Of the requirement for a combined 50 people and jobs per hectare, she says, “I think they may need to be separated so they give a minimum density target for residential and also a minimum density target for employment.”

Has the Growth Plan been a success? “To the degree that for this community in particular, what it was supposed to achieve was development within the built boundary, a mixed range of housing, a live/work community, a walkable community, then yes, I think that has happened,” says Tuckett. “But again, is it a result of the Growth Plan, or has it happened because it was going to happen anyway?”

No more for Mono

While Orangeville is hard at work packing in people, things are more serene in the rural town of Mono. As Mono’s director of planning Mark Early says, “From a rural perspective, it’s a lot different from what Orangeville’s going through.”

“In Dufferin,” says Early, “the Growth Plan puts the onus on the serviced communities – Orangeville, Shelburne and Grand Valley – to take on the growth. There are no built boundaries in any of the rural areas, so all of the intensification requirements have to be accommodated in those three serviced areas. Our hamlets are defined in Mono’s official plan, and we do have fixed limits, unlike a lot of the other municipalities, so that sets out the limit of where they can grow. But all our hamlets are essentially built out.”

Several subdivisions outside Orangeville are technically within Mono, but they were already taken into account. “We had already designated those lands before the Growth Plan and the Greenbelt Plan came out,” says Early. “And they’re all on full services – in fact, all the developments we’ve done since 2000 have been on full services – meeting the intent of the Growth Plan.”

Between now and 2031, Mono’s population is forecast to grow by only 875 people, to 9,770 from 8,895. “From our perspective in Mono,” Early says, “the Growth Plan really had very little impact. With our more recent developments, we knew we had to increase density, and some residents complained about it, but high density in Mono is low density everywhere else. I mean, we’re talking 60- and 70-foot lots.”

Though there may be a tendency to think of the Growth Plan as sweeping change, Early says that, in fact, the plan came late to the party. “A lot of our policies were already in place,” he says. “Then it was, ‘Here’s the plan, now implement it.’ For us, there was not a lot to do because we were already there. We saw that with the Greenbelt Plan as well.”

Mono currently has only two small development areas remaining, and neither is proposed for full services. One in Hockley Village is a plan from 1990 that doesn’t have a sunset clause, and the other is just north of Orangeville in the vicinity of Robinson Road. It was designated in the 1970s.

Though Mono may be full, the same is not true of the rest of Dufferin County. “There is land throughout rural Dufferin where there is still some potential for growth, in some of the hamlets,” says Early.

Describing the Growth Plan as “more provincial rhetoric than anything tangible,” Early believes the plan needs to be more mindful of the rural areas of the outer ring. “What works in Mississauga is not going to work in Grand Valley, yet the plan applies the same everywhere,” he says. “That’s the shortcoming of the Growth Plan … there was no allowance in that regard. It’s one cookie cutter for everybody. There needs to be something put in there for rural Ontario.”

More Info

Understanding the fundamentals of the Growth Plan

The Neptis Foundation’s discussion paper (which can be accessed at neptis.org) examines three broad themes:

- the municipal land budgeting process, which is used to designate land to accommodate growth

- the amount of land already available, and whether the Greater Golden Horseshoe is running out of land for development

- whether the Growth Plan is reducing the rate of land consumption

Neptis on land budgeting

“It’s no wonder that people find this process difficult to understand and that the outcomes can vary widely. To summarize, the final land budget, which determines how much land gets designated, varies according to:

- assumptions about housing diversity (more or fewer detached houses or apartments)

- assumptions about expected types of employment and their land requirements

- variations in the intensification target in outer-ring municipalities

- variations in the amount of land considered undevelopable and omitted from the calculations (“takeouts”)

- variations in the greenfield density target in outer-ring municipalities.”

Neptis Foundation: Understanding the Fundamentals of the Growth Plan

Pulling the levers

The province’s 10-year review is an opportunity to refine Places to Grow to better achieve its goals. It is also an opportunity to more closely integrate the plan with the province’s transit plan, known as The Big Move.

The Neptis brief raises eight key questions it says must be answered by the 10-year review:

- As municipalities begin to plan for the population and employment forecasts in the amended Growth Plan, is it necessary to designate more land for development, given evidence that outward expansion has already slowed down?

- How can we better integrate and align the region’s land use and transportation plans?

- Should municipalities that make their land supply last beyond 2031 be rewarded with priorities in transit investment? Linking infrastructure with the implementation of Growth Plan priorities was part of the early conversation around the Growth Plan.

- How can municipalities account for shifting demographic trends in their land budgets and make the process more transparent and understandable?

- Are the targets helping municipalities achieve the wider goals of the plan?

- How can policies encourage a greater diversity of housing forms, including those that may be more affordable than the current stock?

- What research is needed on the relationship between population and employment forecasting and municipal debt if Ontario is to continue its approach to planning for future growth in a fiscally responsible fashion?

- How will the province begin to monitor the implementation of the Growth Plan in future? Will a monitoring framework be one outcome of the Growth Plan review?

Related Stories

10 Years of the Greenbelt

Jun 16, 2015 | | EnvironmentOntario launched the Greenbelt Plan’s 10-year review, which is taking place concurrently with reviews of the Niagara Escarpment Plan, the Oak Ridges Moraine Conservation Plan & Places to Grow.

Finding Balance in Caledon: The Urban/Rural Divide

Jun 16, 2015 | | EnvironmentIn less than two decades Caledon’s population will be 75 per cent urban. Can its countryside values survive the shift?

I haven’t read through your entire report on the Places to Grow (et al.) planning led by our Ontario government. It’s too astonishing.

Caledon was a quiet region of farms and the Credit River. Not now, with a planned population of 113,000 wedged into tightly spaced houses among huge industrial and commercial plots. Some years ago I was appalled by a large empty space stretching from horizon to horizon, totally denuded of trees but covered with roads, curbs and street lights, just south of the headquarters of the Credit Valley Conservation.

Then there are the gravel pits that are now permanent ponds because pits that penetrate the water table are excused from mandatory reconstitution, and the new six-lane highway about to pierce Caledon’s forests. And all this in spite of the Greenbelt, Places to Grow, Niagara Escarpment and Oak Ridges Moraine restrictions. No wonder Caledon needs 15 planners.

The irony is that Caledon could go bankrupt trying to maintain this monster, whereas if they remained rural, they would now and in the future be quite comfortable.

Another appalling thought is that, despite one of the strictest tree-cutting bylaws in Ontario, Caledon is rapidly being scraped clear of mature tree cover because the Municipal Act exempts industry, commerce, gravel pits, power lines and housing developments from the restrictions. Only farmers, who maintain their woodlots out of self-interest, are controlled.

Meanwhile, towns like Atikokan and Thunder Bay are losing people.

Is there any limit to the stupidity of Queen’s Park “planners”?

Charles Hooker from East Garafraxa on Aug 10, 2015 at 7:03 am |

The trio of articles in the last issue, on the Greenbelt, the Growth Plan, and Caledon’s rural / urban divide, distilled a lot of excellent research and regional wisdom. The key perspective of long-term ecological integrity, however, begged greater attention. While conservation authorities are developing and implementing innovations to better protect natural heritage and water, they are not afforded the political respect nor the resources they need. In particular, while section 2.2.1 a of the Provincial Policy Statement requires planning authorities to protect, improve or restore the quality and quantity of water by “using the watershed as the ecologically meaningful scale for integrated and long-term planning, which can be a foundation for considering impacts of development”, watershed planning lacks teeth and consistency. Worse, monitoring and reporting are woefully inadequate: from individual conservation authorities, the Conservation Authorities Moraine Coalition, and the Province – a fact that is significantly hampering the on-going land use planning review. While some rules may irritate, ecological integrity is required for a healthy population and a vibrant economy, and must be protected for future generations.

Andrew McCammon, Executive Director

The Ontario Headwaters Institute

Oakville, Ontario

Andrew McCammon from Oakville on Jun 18, 2015 at 7:16 am |