The Red River Rebellion: The Hills Get Indignant!

There was the button that always cranked these hills beyond reason – the hint of anything Fenian.

The Red River Rebellion (1869-70) was over a thousand miles away and rather tame as rebellions go, but it stirred the citizens of our hills to hold “indignation meetings,” a uniquely 19th-century style of protest.

A dent in Canada’s story

Canadians revel in the claim that this nation was born without a shot being fired. Well, not quite. Our fifth province, Manitoba, joined Confederation in 1870 amid armed conflict and gunfire. The situation flared up in 1869 in the Red River Colony, an area settled by Métis, the descendants of Scottish and (mostly) French-Canadian voyageurs who had married Aboriginal women.

Although it was a British colony, Red River was administered by the Hudson’s Bay Company because it lay in Rupert’s Land, the vast territory controlled by the giant fur trader. What got things going was the biggest land transaction in world history. In late 1869 Canada acquired Rupert’s Land, one-quarter of the entire North American continent, for $1.5 million.

During the negotiations, neither the Canadian government nor Hudson’s Bay paid the slightest heed to the Métis and whether they owned the farms they had been working for half a century.

To force the Canadian government to recognize them and negotiate, the Métis seized Fort Garry (site of the Hudson’s Bay Company’s headquarters in what is now downtown Winnipeg), and set up a provisional government led by Louis Riel. They then promptly raised the bar by refusing to let Canada’s newly appointed lieutenant-governor enter the territory. By January 1870 the situation had become an armed standoff.

Why the fuss here in the hills?

At first glance, the Red River Rebellion seemed utterly irrelevant to, say, a farmer in Mono or a storekeeper in Erin, but Louis Riel and the Métis had pushed some hot buttons. To begin with, Ontario in 1870 was British, Protestant and Orange, and these hills were solidly ensconced in that spectrum. Riel was French-Canadian and profoundly, even mystically, Roman Catholic. And it didn’t help that his statements regularly referenced the authority of Quebec bishops. This at a time when at least one MP in these hills, T. R. Ferguson of the Cardwell riding, was known to drop the derogatory term “papist” into his speeches with impunity.

Religious tension was not the only button. The Orangeville Sun, in a January 1870 editorial, summed up a widespread Canadian anxiety with an editorial beginning, “The ruling passion of the United States is thirst for Empire.” It went on to articulate what many Canadians feared – that Riel’s rebellion was an opportunity for the U.S. to seize the great northwest.

As the Brampton Conservator pointed out, Canada needed only to reflect on how the U.S. treated Mexico to see what might happen here. The threat was real, for the British army had been almost entirely withdrawn from Canada following Confederation in 1867, and although militia regiments like the 36th Peel were being trained and strengthened, they were no match for the huge army south of the border.

Finally, there was the button that always cranked these hills beyond reason – the hint of anything Fenian. Riel was actually opposed to the Irish nationalists and their objectives, but there were Fenians in Red River, and when rumours reached Ontario that a contingent was organizing in Minnesota for a push north, it inflamed the situation even more.

Riel lights the fuse

Thomas Scott (1842-1870) apparently did himself no favours with his obstreperous behaviour and foul mouth. In jail at Fort Garry even his fellow prisoners petitioned to have him moved elsewhere. Speakers at indignation meetings, on the other hand, called him “intrepid, determined, and outspoken.”

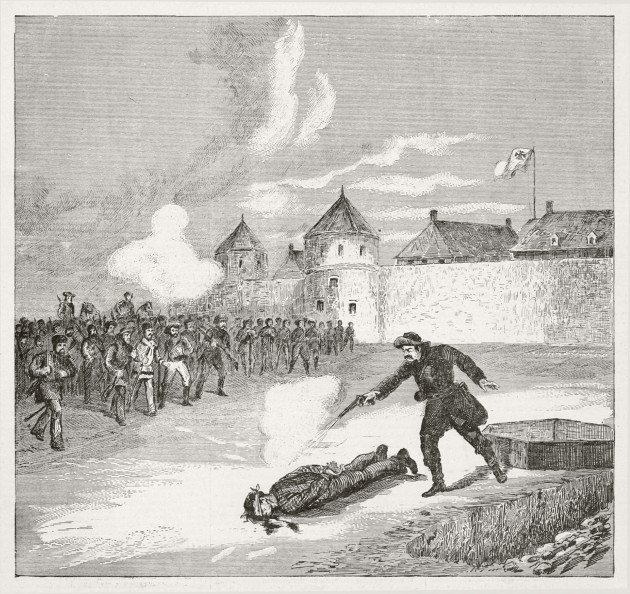

On March 4, 1870, Louis Riel authorized the execution by firing squad of Thomas Scott, who had been captured in a failed opposition attack on Fort Garry. To the Métis, Scott was a symbol of the Canadian government’s messy takeover of Rupert’s Land for he was a surveyor, one of the men laying out plots on farms the Métis believed they owned.

Scott was also a loud voice in the local opposition to the rebellion, a force made up mostly of former Ontarians who had gone west because Crown land in areas like these hills had been pretty much taken up. Though small in number, they added a civil war component to the rebellion, mild in comparison to more famous conflicts, but enough to generate several armed confrontations.

Although Scott’s was not the first death in the struggle, he was from Ontario and he was British, Protestant and Orange. And so, what had been for several months a disturbing but far-off situation was now a full-blown crisis.

Taking out the frustration

How indignation meetings developed as a form of peaceful protest is uncertain, but they were a well established practice by 1870. Remarkably democratic – anybody could organize one – they were also quite structured. The meeting on April 19 at Orangeville’s Middleton Hall was typical. A secretary (W.R. Raines) took notes while chairman F.C. Stewart kept order as speakers in turn denounced Riel, decried the government’s slipshod handling of the crisis, and otherwise expressed outrage. At the end of the meeting a unanimous vote called on the government to crush the rebellion.

The meeting secretary was instructed to transmit the results of this vote to J. Ross, MP for Centre Wellington, and then everyone, depending on their attitude toward temperance, went to a tavern or home, warmed by the satisfaction that they had made their point – the very reason for holding an indignation meeting.

Such meetings varied from nearly a hundred people in Orangeville’s gathering, to a rowdy 10,000 at an open air affair in Toronto, to the average dozen or so in the Orange Lodges of the hills. A meeting in tiny Sandhill prepared for over 300 participants in expectation of a delegation from Brampton where, curiously, there is no record a meeting was ever held, despite the high-tension editorials in the Conservator. Even more interesting, there is no record of a meeting in Bolton where, according to James Bolton’s history of the town (published in 1931), Thomas Scott’s brother Hugh was a bookkeeper at the mill owned by J. Gardhouse. But it could be the momentum for indignation meetings was sidelined by rapid government action.

No more need for indignation

Maybe the indignation meetings did the job or maybe it was smart politics, but after dithering for months, the government in Ottawa acted in days. By the end of April 1870 an armed expedition of 800 militia and 400 British regulars was organized to put down the rebellion. (They reached Fort Garry in August, long after the dust had settled.)

In May, the new province of Manitoba was created, effectively ending the rebellion, even though the Métis were still not satisfied. And early in June – a fortuitous gift perhaps – the Fenians were solidly defeated by Canadian militia (in Vermont) in what would be their last ever attempt to invade Canada.

Only two months after the hills got indignant, the Sun was waxing eloquent about a bumper wheat crop while the Conservator found space for a half page on a ball game between the Brampton Mechanics and the Acton Pastimers. Red River had disappeared from the news and indignation had melted away. Summer in the hills, it seemed, was going to be warm and peaceful.

Ontario’s indignation was fired by this woodcut, “The Tragedy at Fort Garry, March 4, 1870,” an artist’s conception of the Scott execution at Fort Garry. The anger was made even worse by rumours that Scott was buried alive and was heard screaming in the coffin at his burial. Library and Archives Canada, C-048776

More Info

Hanging Riel in Caledon East

Louis Riel was charged with treason and hanged on November 16, 1885 in Regina, following the second Métis rebellion he led, this time in Saskatchewan. On November 5, 1886, just shy of the first anniversary of that hanging, one Pat Riel, a labourer for Silas Roadhouse, was drinking in a hotel in Caledon East and when asked by other patrons to introduce himself, dutifully gave his name. In what began as a prank, several patrons, apparently in their cups, held a mock trial of Pat Riel, secured a rope and began a simulated hanging from a hook in the ceiling. The rope stuck in the hook and Riel was nearly strangled. He was saved by the quick work of Richard Evans, a magistrate from Sleswick who urged Riel to press charges, but he declined.

“The very model of a modern major general”

The aria from The Pirates of Penzance is arguably the most famous in the Gilbert and Sullivan operetta repertoire. It is a spoof of Field Marshall Sir Garnet Wolseley, among the best-known British generals in the Victorian era. While still a colonel, Wolseley was stationed in Canada and in April 1870 was given command of the Red River Expedition.

The expedition (which included teamsters from these hills but no militia) sailed from Collingwood to present-day Thunder Bay and then traversed miles and miles of trackless wilderness (towing cannon) to present-day Winnipeg, arriving on August 24. The rebellion was long over and Louis Riel had fled to the U.S., but Wolseley was quite rightly celebrated for his peaceful takeover of Fort Garry, and especially for getting there through the impossible terrain. Little known is that he hired Métis guides to accomplish the latter task.

The Patrick Riel in this story is a relative of mine. He was the son of John Riel, my great-great grandfather. As I have been researching my family history in Ontario I would be interested in finding out where the material for this article came from and if there are any more details to the tale.

Kerry Banks on Jan 1, 2017 at 4:49 pm |