Once a Village

The 19th century saw tiny villages spring up all over these hills, bearing sturdy names like Lockton and Elder, unusual names like Biggles and Shrigley, and pretty names like Camilla and Silver Creek. They faded away, but left a legacy that helped create the hills we know today.

In some cases the memory of those early villages – hamlets really – is reinforced by a building that still stands, a one-room school, for example, more often a church. In Silver Creek, on Kennedy Road north of The Grange Sideroad in Caledon, red brick St. Cornelius, built in 1886, rises proudly against the horizon. The United Church (originally Presbyterian) in Camilla, an 1880 structure, also still stands, just west of Highway 10 on Mono’s 15 Sideroad. There never was a school in Lockton at the junction of The Gore Road and Patterson Sideroad in Caledon, and a wood frame church that stood farther west is long gone, but in what became a thriving village in the 1880s, two of the original houses, one built before 1840, still grace the intersection.

For the majority of the once-upon-a-time communities, however, places like Earnscliffe on the 5th line of Mulmur, or Tarbert just north of Grand Valley, or Shrigley in the northwest reaches of Melancthon, no such structures are left to tell their story. Even for a busy place like Craigsholme, where a hotel, store, school and post office once serviced the area at the junction of Dufferin Road 3 and the East-West Garafraxa Town Line, the village is preserved only in archival records and historical memory.

A shrewd observer

One of the most interesting archival records is a report on the state of local communities written in 1878 by John Foley, founder of the Orangeville Sun. It was the result of a week-long, unofficial inspection tour by horse and buggy.

Travelling along what is now Highway 10, after pausing in the hamlet of Biggles (at Mono’s 5 Sideroad), Foley made his first overnight stop at Camilla, population c. 100. There he listed a hotel, general store, a gristmill, sawmill, shingle factory, wagonmaker, blacksmith and two resident ministers (Presbyterian and Methodist). He stayed at the hotel and described himself “kindly treated,” but observed, without explaining why, Camilla “has ceased to be what it once was – quite a little business place.”

The next day took him east through nearby Mono Centre, where he noted the retail and service offerings were similar to those in Camilla – and expressed surprise the general store actually seemed busy. He then continued east to Relessey at Mono’s 5th Line. By now it was clear Foley’s trip was devoted to evaluating the commercial potential of each community, for here he noted again that Relessey’s commerce was just like that in nearby Mono Centre and Camilla. (At the 4th Line he could have gone north one sideroad to Elder, population 50, where the retail and service enterprises were also similar.)

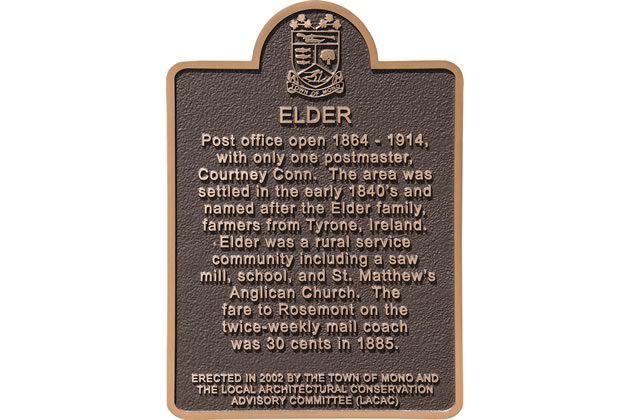

Elder is now a sleepy wooded intersection marked by a plaque. Photo by Pete Paterson.

Relessey’s two churches, wagonmaker, blacksmith shop and general store left Foley unimpressed for he pronounced the hamlet “not likely to become a place of any importance,” and he turned northeast to Rosemont. There he commented that even though Rosemont “once gave promise of becoming a smart business place,” the community had been bypassed by the railroads and now was limited to local trade. He underlined this observation during a stay in fast-growing Alliston. At one time smaller than Rosemont, with the new Hamilton and Northwestern Railway line the community was now guaranteed “a bright and prosperous future.”

Foley’s return journey took him through Sheldon, population c. 80 (commercially identical to the other small communities but distinguished by an excellent water-powered gristmill), and on to Hockley. Although it “gently slumbers in the Valley of the Nottawa,” he felt there was prospect of the village becoming a lively business centre one day. Regrettably, he did not explain why, perhaps because he was focussed on his final stop, Mono Mills.

Sheldon’s once thriving mill property is now a private estate. Dufferin County Museum & Archives P-068A.

In 1878, John Foley would have been well aware that less than a decade before, the Toronto Grey and Bruce Railway had bypassed Mono Mills and made Orangeville its central hub, providing a mighty impetus to the town. The original plan had been to make Mono Mills the hub, but when rumour of an impending railroad route sent property values soaring, the TG&B ran the tracks on less expensive land farther west.

In his report Foley echoed the accepted opinion about Mono Mills’ commercial future – “the trade of the village must always be limited to the current trade” because the railroads were “diverted into other channels.”

Keys to development

The coming of railway determined the fate of many early communities. Those on the rail route, like Orangeville, thrived; but those that were bypassed often went into decline. Pictured is a train on the trestle bridge at Forks of the Credit, c.1886. Region of Peel Archives / PAMA PN2009.

There is no question that in the late 19th century railroads brought progress. On the TG&B’s route Bolton grew dramatically after the trains first arrived in 1869. Shelburne, once little Jelly’s Corners, was another beneficiary. But other factors also contributed to the development of a community in the mid-1800s, and significant among those was flowing water. Silver Creek was a good example.

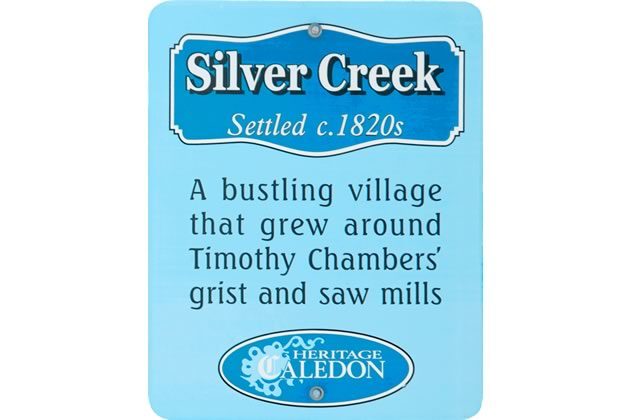

Silver Creek, the stream, is a tributary of the Credit River and in the mid-1820s Timothy Chambers used its flow to power a gristmill he built on its banks. Next up, as so often happened, there grew Silver Creek, the village. By mid-century it had, inevitably, a general store, a blacksmith and a wagonmaker. A post office was granted in 1858 (officially changing the community’s name to Caldwell, a designation most local residents studiously ignored), and by 1877 the population reached 150. There was a school and St. Cornelius church. In 1886 the church became the most prominent building in Silver Creek when it was reconstructed with red brick. There had been two earlier wooden versions, the first built in 1834 (ironically giving predominantly Protestant Caledon Township a parish before the adjoining predominantly Catholic Albion Township got one).

Silver Creek was further distinguished by having three hotels. Before railroads ran north from Lake Ontario through these hills, the little community was stop number two on the oxcart trail from Port Credit to Owen Sound, so hotels were crucial. The coming of the railroad, or perhaps the not coming of the railroad, to Silver Creek meant its growth levelled off, declined and ultimately faded. Had the village been located at a crucial intersection, Silver Creek as a settlement might have hung on a bit longer, because intersections also mattered.

In Silver Creek, St Cornelius Church and the schoolhouse, since converted to a residence, are all that remain of the bustling village.

Silver Creek, Settled c. 1920s – A bustling village that grew around Timothy Chambers’ grist and saw mills.

Where the roads cross

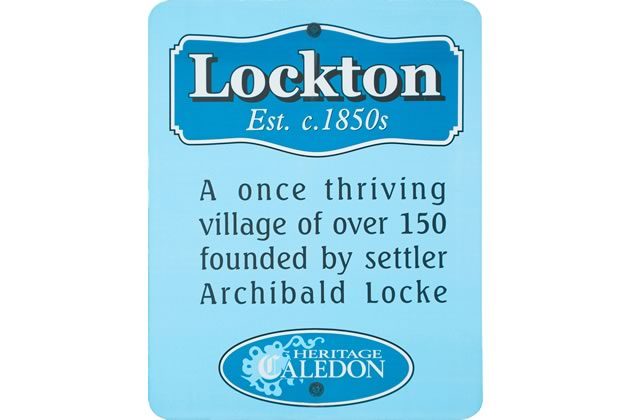

In the early days of these hills, where a reasonably maintained north-south road crossed one of similar quality running east-west, it was not unusual for a tiny urban node, a service node, to develop even if significant water power was nowhere nearby. In the era of horse and foot power these nodes were particularly successful if larger commercial centres were inconveniently distant. Lockton was located in one such circumstance.

In 1845 Archibald Locke (Jr) developed a village plan of subdivision (this never happened in Silver Creek) and became a dry goods merchant, a postmaster and the innkeeper of the Rossney Hotel. By 1875 there were two more stores, a milliner, a soap and candlemaker, and as always, a shoemaker, blacksmith and wagonmaker, together serving the surrounding farms and a local population of about 150. Lockton even boasted three doctors (possibly of dubious certification).

This community served its fairly prosperous neighbourhood in a manner somewhat analogous to today’s convenience stores. Although not much different from other once-upon-a-time villages, Lockton’s location seemed to make it more successful and it lasted a little longer.

Only two houses remain in the former village of Lockton, including this one, built in 1840 or earlier. Photo by Pete Paterson.

One of two houses that remain in the former village of Lockton. Photo by Pete Paterson.

A decline both dramatic and subtle

Although railroads – there were three different systems in the hills by 1880 – pretty much halted development in the villages they bypassed, it didn’t doom them. Improved roads did that.

Even before the automobile, better roads – especially maintained roads – meant Lockton’s consumers could make return trips comfortably to larger centres such as Caledon East or Bolton. It was only natural that the more extensive retail array, professional services and entertainment these centres offered were more appealing. Roads had a further devastating impact on villages such as Camilla where homes and commercial buildings hugged the edges of the thoroughfare. Even though a general store and a gas station hung on in Camilla well into the 20th century, several widenings of Highway 10 not only physically split the village but sealed its fate because key buildings had to go.

Only Ebenezer Church (c.1870) and cemetery still stand in Relessey. Photo by Pete Paterson.

A more subtle harbinger of decline for some villages was the closing of local post offices. In places like Relessey, Elder and others, the post office was usually located in the general store, a major perk for the owner. Citizens coming to collect or post their mail ensured regular traffic, and a clever storekeeper would put out a few chairs next to a pot-bellied stove where customers could linger and gossip – often a major reason why patrons chose the village store over a larger centre to purchase goods. But by 1914, rural mail delivery was instituted and most small post offices in Ontario were closed (Camilla’s lasted till 1935; Mono Centre’s till 1969), removing another spoke in the wheel that helped keep tiny villages rolling along.

Local hotels, another gathering point, disappeared as well – they simply became uneconomical. (On his tour in 1878, John Foley had noted he was “kindly treated” at Hugh Currie’s hotel in Camilla. Local legend says that “kind treatment” once flowed to the hotel through underground pipes connected to a still in Currie’s barn. Foley was a known abstainer, but given Ontario’s long history with prohibition, perhaps he was subtly acknowledging an effective strategy.)

However, “spirit” meant much more than alcohol at places like Currie’s hotel. In those early villages a hotel was a community centre. Camilla’s Tweedsmuir History reports as many as 12 square dance sets (96 people) could twirl at once in Currie’s, with room along the walls for those in wait. The Rossney Hotel in Lockton offered what it called a dancing academy, where people gathered from miles around for social events.

Some have gone. Some remain.

Once a community’s hotel was gone, a lot of its vitality and spirit left too. Currie’s, after a number of ownership changes, was lost to Highway 10. Rossney’s burned down. According to historian Esther Heyes, once Rossney’s was gone and the Burrell family moved their general store to Caledon East in the early 1900s, Lockton’s fate as a community was sealed. (The general store is now one of the two private homes that mark the intersection where Lockton once grew.)

On the other hand, it may have been spirit alone that kept alive some of the small villages that, like Relessey, John Foley probably believed were doomed. Mono Centre, for example, where the general store (ready to close by 1950) has become a successful restaurant, never seemed to lose its spirit of community. Restaurants have also kept Rosemont alive and well. Although it continues to “gently slumber in the Valley of the Nottawa,” Hockley likewise continues to show the promise Foley observed in 1878.

Although they are still small, these communities appear to have nurtured a core with a gravitational pull well beyond their own borders. For most of the tiny villages though, once their stores and services became redundant (or suffered a crisis, as was the case for Sheldon when fire destroyed its thriving mill in 1963), the end was inevitable. By the end of World War I, Silver Creek, for example, was almost empty. On the edge of Silver Creek it’s still possible to see traces of the gristmill that in 1866 produced 50 barrels of flour a day, but aside from the church, a few family homes and the school, now a private residence, little remains of the once bustling community.

In Relessey, which began as MacGuire’s Corners in 1840, a red brick church (built 1870) stands nostalgically beside a cemetery on the southeast corner, but there is nothing else there. Even the Orange Lodge which absorbed Sheldon’s lodge in the 1960s is represented only by a memorial plaque. Without its heritage sign Lockton would go unnoticed by anyone driving past. There is no store, no evidence of commerce and the buildings are gone. The blacksmith shop became a chicken coop before, like the wagonmaker’s shop, it was torn down.

In the tiny villages that disappeared, most of the first homes were log or frame and once commerce evaporated, the homes too were eventually torn down or abandoned to the elements, slowly decaying into “ghost villages.”

A legacy worth preserving

On open land that once touched the west edge of Camilla there is now a pleasant subdivision, though there is no store and there are no inviting chairs next to the community mailbox. Camilla, Silver Creek, Biggles and others like them will not rise again, but their legacy is worth preserving.

In 1886, when Roman Catholic parishioners undertook to rebuild St. Cornelius church, the members of Silver Creek’s all-Protestant Orange Lodge, L.O.L #185, drove their wagons to Orangeville to get the bricks. The Lodge and most of the other buildings are gone, but the church still stands on the hill and mass continues to be offered every Sunday. It is a rare and tangible testament to the generous spirit of a long-ago village that helped define the best of the community we cherish today.

More Info

Communities blend

By the beginning of the 20th century some of the hills’ tiny villages were being absorbed by larger, expanding communities. The 1877 Historical Atlas of Peel County, for example, shows subdivided village plans for Glasgow on the northwest edge of Bolton and for Nunnville on its southeast edge. Neither Glasgow nor Nunnville were ever incorporated and both became part of Bolton. On what is now the northeast edge of Bolton stood the tiny – and separate – village of Columbia. It had a post office from 1858 to 1913 which required changing its name to Coventry. Columbia-become-Coventry too is now part of Bolton.

A shifting population

In the early 1900s, the opening of the Canadian West was one of several factors along with economic depression that caused a severe decline in the population of Dufferin County and, to a lesser extent, present-day Caledon and Erin. This decline was particularly represented among the sons and daughters of settlers who first farmed the marginal land of the Niagara Escarpment and who saw little future in working a soil unfriendly to traditional agriculture. Some estimates state a population drop as high as 20 per cent in Orangeville and the immediately surrounding area. Losing people was yet another reason why the tiny villages of the hills gradually faded away.

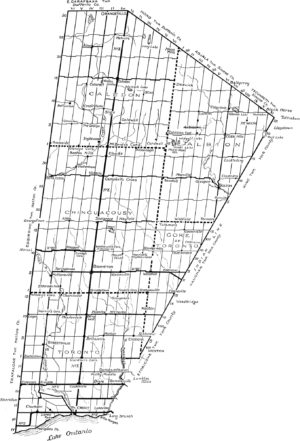

Maps – click for larger image

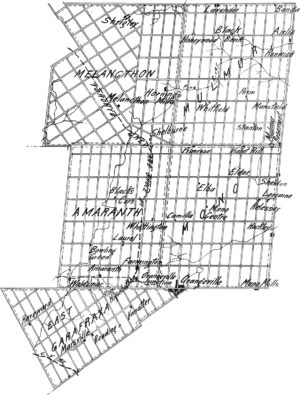

A 19th-century map of Dufferin County shows Elder, Relessey and Sheldon – little evidence of the formerly busy villages is visible today.

A 1933 map of Peel includes the names of early villages, many of which are today marked only by a heritage sign.

What a great article. Mono Mills is celebrating its 200th birthday this year and I am working to gain as much information about our village. So many photographs have been lost, misplaced, or in bins somewhere I’m sure. But one thing is prevalent here and that is that the railroad bypassed Mono Mills. Many stories are being told throughout our community, and we still have founding family members here with rich history. Once again, thank you for this great story of travelling through many of our small villages that were once bustling communities.

Charlene Buckley from Mono Mills, Caledon on May 23, 2019 at 10:57 am |