Rosemary Kilbourn: Light, Line & Lyricism

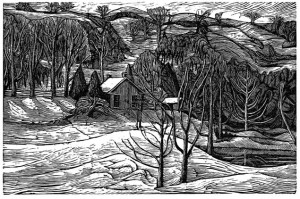

From the moment she moved into her rural hideaway, Rosemary Kilbourn began to interpret the landscape right outside her door and windows.

The “Dingle Schoolhouse,” home and studio of Rosemary Kilbourn, one of Caledon’s most thoughtful and talented artists, is set in a wooded valley surrounded by conservation lands along a moraine that forms part of the Niagara Escarpment.

At the Dingle Schoolhouse, in the shelter of the escarpment, wood engraver Rosemary Kilbourn has found a lifetime of inspiration.

Kilbourn first saw the schoolhouse in 1957 in the company of painter and war artist Will Ogilvie, who had a sketching cabin nearby. The derelict school was “boarded up, and covered in tarpaper, with a frost-heaved floor and no hydro,” she says, “but it looked like the answer to my long-held dream of living in the country… The fact that it was a mile and half from the road was an added bonus.”

The school had been constructed in 1872 on the former Second Line Albion, but the road had never been more than a rough carriage route for the school’s students and families picnicking in the nearby dell, or “dingle,” and had long since been closed off.

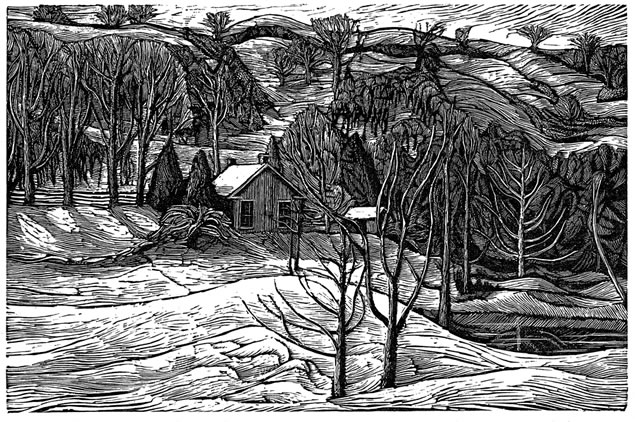

From the moment she moved into her rural hideaway, Rosemary began to interpret the landscape right outside her door and windows. The schoolhouse was perfectly placed for her to describe her close and continuing relationship to the land. It was sheltered by the escarpment on one side, with long views across gently rolling countryside on the other. Over the years, those views have been slowly closed off by reforestation and natural regeneration, and the row of maples planted by long-ago school children beside a long-gone road are now gnarly giants, guarding her kept gardens from the wild wood beyond.

Each time I walk or drive along the long road to the schoolhouse, I feel as if I am being transported to a different dimension altogether – as if the meandering lane is an avenue to earlier times.

On my first visit to Rosemary, she cautioned me to be careful because a recent snowy rain could have flooded the lane where it skirts a low-lying pond. I had to be aware of the weather as much as the elaborate and detailed directions she had given me in order not to get lost on the wending trail.

The road, I discovered, was passable and safe, following the lay of the land as it brushes by rocky outcrops and streams. By travelling along it, I began to appreciate the lines and rhythms of the landscape that inspire Rosemary’s work.

Rosemary’s studio is in a large addition that hugs the original building. From its westerly floor-to-ceiling window, she looks out on a landscape that is lined by the gestures and caresses of ancient geological events. As she pointed out various features of the landscape, her gentle commentary mixed fact and anecdote, personal history with elaborations on those ancient events that formed the hills and valleys we gazed upon.

She drew my eye to the dramatic interplay of the planes and folds of the hills, and the furrows and creases that meander along in the distance. It was not difficult to imagine the land as a living presence with the Dingle at its heart.

____________________

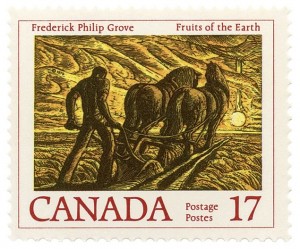

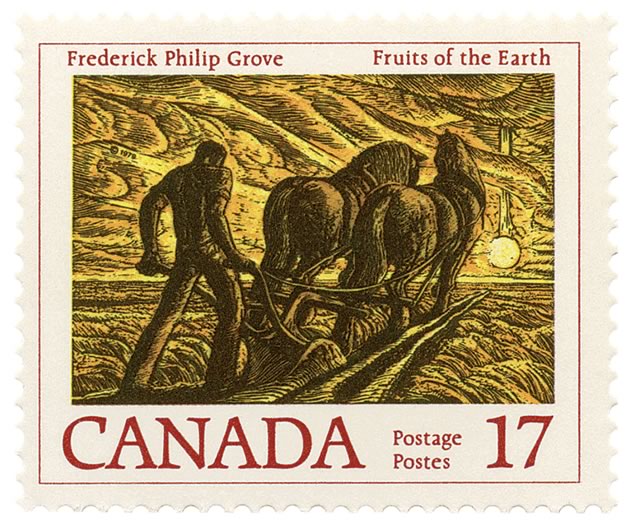

This image, commissioned by Canada Post as one of a series of stamps commemorating Canadian authors, illustrates the 1933 novel, Fruits of the Earth, by Frederick Philip Grove.

Over the course of a pleasant morning’s visit, lunchtime conversation, and time spent studying her work in her studio, I came to realize how deeply attuned Rosemary is to the personalities and tempers, moods and emotions of this corner of the Caledon hills. She knows this environment by the truths that observation supply to the senses, and she translates this knowledge into her art. As an artist she is a participant in a complex choreography among the natural elements.

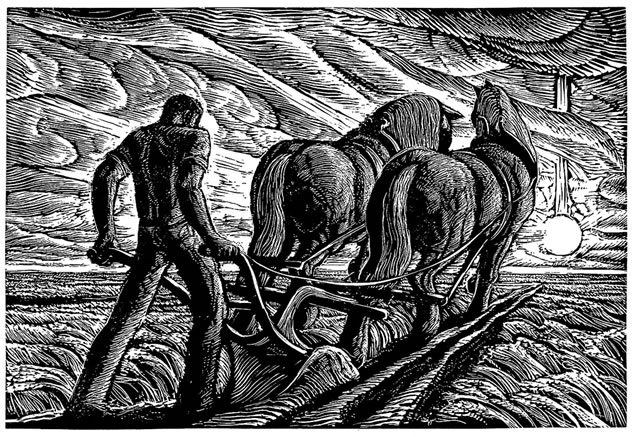

In a corner of her studio, Rosemary showed me where she carves the blocks of wood that are used to print her images. I became a student as she led me through this process-laden form of image-making that draws its inspiration from late-nineteenth and early twentieth-century English wood engravers.

Rosemary said she began painting “with serious intent” when she was just 11, and she painted virtually daily through her adolescence. As a student at the Ontario College of Art in the early 1950s, she had very little exposure to engraving, and it wasn’t until she arrived in London, England, that she received her brief and only instruction in the craft, from the engraver who sold her the tools. Nevertheless, she was captured by the medium and continued to refine her skills independently.

Her earliest efforts were illustrations for her brother, historian William Kilbourn’s first book – “A good way to make all one’s mistakes public!” she notes ruefully. She also illustrated a book by her neighbour, Farley Mowat.

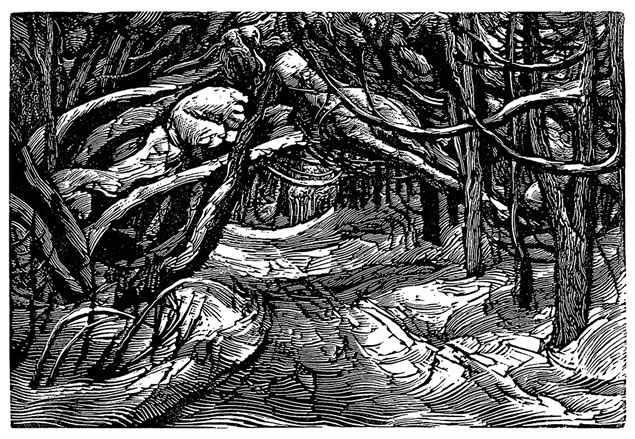

“Some of the elements that I most want to express in landscape are, to some extent, a given in engraving,” she says.

“The first is light. Brilliance comes from the contact of the rich black printed from the surface of the block while every cut into it remains white. The process is like drawing with light. The second is movement. The path of the eye and the direction of the shapes in the composition can be shown and felt by the thrust and flow of the engraver. It also keeps a sense of the spontaneous, even though the design has been redrawn many times. This is a necessity to condense and simplify without being seduced by the realism of the moment.”

Rosemary set aside her engraving tools during the 1980s to experiment with stained glass. Those compositions harnessed the radiance of light to imbue her figurative and Biblical subjects with a dynamic spiritual energy and her work resulted in what she describes as “a fairly steady supply of church commissions.” Even so, she says, she never really felt at home in the medium, and she eventually returned to wood engraving.

Along with her landscapes, mythical and spiritual imagery has been a recurring theme in Rosemary’s work, some emerging from her own reflections and others in response to commissions. There is a sharper, more angular quality to many of those images, compared to the supple, meditative lines of her pastoral work.

What struck me about the intricately detailed drawings and engravings I saw in her studio was the intensity of her artistic vision. The visual energy that flows in and through everything that my eye fell upon around the Dingle Schoolhouse is beautifully suggested in the rich orchestration of the sinuous lines of her wood engravings, as well as the paintings she continues to create. It is as if the land has an intelligence of its own that Rosemary interprets with a mind finely attuned to expressing its vitality and character.

As I made my way back down the roadway in the mid-afternoon light of an early spring day, I felt keenly aware of my surroundings. The intensely visual experience of visiting Rosemary’s studio and her engaging conversation gave me a deeper appreciation of the land and my own place in this small, beautiful corner of the world.

Through her work Rosemary allows us to experience the energy of nature and the sensuality of the land. Her art revealed to me the possibility for unity between viewer and subject – between me and the meandering road that I was on – that can be attained simply by surrendering to a deeply intuitive way of seeing.

Rosemary Kilbourn was one of my teachers in the early ’60s at The New School of Art in Toronto. She certainly made drawing approachable. So I decided to do a bit of research on her life and art. This article and others about Rosemary’s work took me immediately into her unique home, the countryside, her ideas and thoughts about printmaking and stained glass. It is almost like being there. What a treat!

Thank you, Tom Smart.

Caroline Wickham from West Vancouver, BC on Oct 21, 2020 at 10:10 am |

Just wondering whether Rosemary Kilbourn is still active in producing wood engravings? Is she represented by a gallery or how would you go about finding wood cuts. I have a few I picked up at auctions.

DAvid Wall from Morden, MB on Jul 5, 2016 at 12:37 pm |

I came across this article with great joy as it brought back fond memories for me! Back in the late sixties Rosemary hired me as a teenager to help maintain the old school and property painting ,replacing cedar shingles ,cutting grass, etc. Having only met Rosemary a few times before hand I was pleased to see how soon I became comfortable around her, that and the fact my Mother used to attend the old Dingle school made for a pleasant all round experience . Rosemary would make me stop and have lunch in the School house. Wandering around in the school amazed by the art work gave me a sense of who this soft spoken kind hearted lady was. I have often thought about those times and truly miss them ! Perhaps a look into the life of a person more thoughtful and talented than myself, helping me grow a little as a person. I thank her for that and you for this article. For me a lady and a time truly worth remembering !!

Terry Payne from greenstone ont. on May 7, 2014 at 10:26 pm |

When I read Tom Smart’s article about Rosemary Kilbourn’s wood engravings and stained-glass windows (Light, Line & Lyricism, autumn 2011), I was reminded of her exquisite stained-glass window in the chapel at Hart House, University of Toronto.

As you enter this tiny, non-denominational chapel, her strikingly beautiful window is directly before you. I occasionally give tours of the university to relatives, friends and students, and Rosemary’s window is one of my favourite stops.

Paul Aird from Inglewood on Nov 19, 2011 at 4:28 pm |