The Grand River – When Your Neighbour is a River

Not only does the Grand River lay out nature’s beauty, it also offers opportunities for recreation, commerce and development. Yet all this comes at a cost, for the Grand can be both friend and foe.

As March 1929 blended into April, the residents of Grand Valley were breathing easy for a change. In springtime, keeping a wary eye on the Grand River as it loops through town is a long-ingrained community habit. But that year the snow had melted evenly, and most important, the ice cover had floated away without creating a dam. It seemed that ’29 was going to be a no-flood year. Until the afternoon of Friday, April 5.

On that day, the clouds opened with a force no one could recall seeing before. By early evening, town constable Stuckey was visiting village homes along the flood plain urging families to evacuate. By midnight, three feet of water covered the south end of town with a fierce, swirling current. And the level kept rising, for north of the village the normally placid Black Creek was pouring the waters of Luther Marsh into the Grand. By three a.m., water on the road south of the village approached the height of an adult. Power went out. Telephones didn’t work, roads were closed and trains were halted by washouts. Grand Valley was in a crisis and on its own.

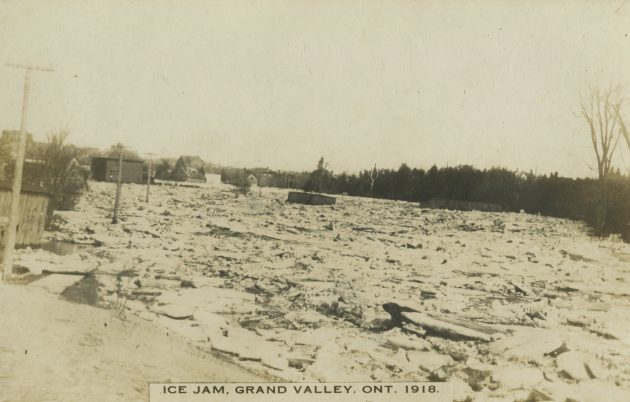

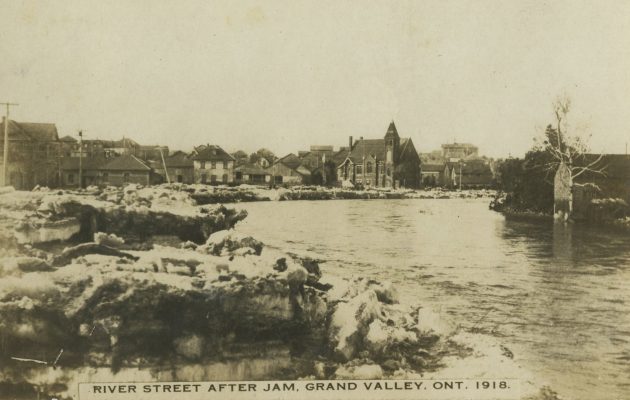

Before (and even after) the Luther dam was built, Grand Valley was accustomed to annual spring flooding, but some years were worse than others. Although the village escaped much of the damage its neighbours experienced in the great flood of 1929, the flood of 1918, shown here, made for one of the bad years. Dufferin County Museum and Archives P-3841-007.

Nothing new about a flood

Yet as dawn broke it was evident the people of this town were used to life on the river. Boats were on the streets moving some residents to higher ground, delivering supplies to others. John Reith was rowed from his home, literally on an island, to his business on Main Street. (He opened at noon.) George Maxwell, the village blacksmith, had moved his horses to the second floor of his shop at midnight and was already refiring his hearth. The mailman picked up the day’s mailbags at the railway station and rowed along Main Street making deliveries – on a Saturday! Even the village livestock seemed to know what to do. Mary Small had lost her chickens, but most villagers reported that flocks simply stayed up on roosts until the water receded.

And recede it did. The flood that had risen with such speed went down the same way, so that by late Saturday afternoon the river, although greatly swollen, had pretty much returned to its natural course. In the great flood of ’29, Grand Valley had gotten off easy. Nearby Waldemar, well above the riverbank, had also escaped. But farther down the Grand – indeed throughout Southern Ontario – there was utter devastation.

The flood of the century?

It was not until several days had passed and services were restored that Grand Valley learned just how bad and how big the storm had been. Downriver, the water’s fury had caused enormous damage in Fergus and Elora. In Guelph, where the Grand added the Speed River to its flow, a dam collapsed, inundating that city and then Kitchener, Galt and Brantford, causing damage in the millions.

Elsewhere, rivers smaller than the Grand had gone on a rampage too. Just north of these hills in Grey County, one township alone lost more than 50 bridges. Owen Sound was isolated for two days. Oshawa became a refugee centre as trains from all directions had to back up into the city because of washouts. Orangeville, as it turned out, was one of the few communities left relatively untouched, though a number of residents had to abandon their cars in the unpaved mud of Highway 10.

Arguably, this flood had more serious consequences in Ontario than Hurricane Hazel, 25 years later. Though there were fewer fatalities – eight compared with 81 in Hazel – the damage geographically was far more widespread. Either way, the impact for neighbours of the Grand River after the flood of ’29 was similar to that for neighbours of the Humber River after Hazel. Everyone agreed that flood control in the watershed was necessary and urgent.

Managing the Grand River

The idea of flood control was not new; it had been bandied about for years, a crescendo rising with the annual spring floods and then fading with the – also annual – drying up of the Grand River to a mere trickle in summer. But the flood of ’29 coincided with the beginning of the Great Depression and the cry for public works, so that by 1942 the Shand Dam was completed just upstream from Fergus, dramatically enlarging Belwood Lake. Then 1954 saw the completion of the Luther Dam, effectively creating Luther Lake in the great Luther Marsh.

Coincidentally, war affected the building of both dams. A shortage of materials at the beginning of World War II delayed the Shand, while the onset of the Korean War raised fears of another shortage – and this spurred the building of the Luther Dam.

The two dams turned the Grand River into a more amenable neighbour. Both established flood control along the river’s length, but the flip side, “flow augmentation” – managing the annual summer trickle – may have been even more important. Communities need water to grow, and before the dams were built many of the Grand’s neighbours had reached the limit their wells could provide. Now with Belwood and Luther lakes reserving spring floodwaters for release in summer, decades of municipal prayers were answered.

The ultimate neighbourly statement?

In 1994 the Grand River was recognized as a heritage river, not for its size, even though it’s the largest located entirely in Southern Ontario, nor for its beauty, even though it’s among the province’s most scenic, but because of its “harmony with the human settlement around it.” A friendlier phrase to describe a neighbour is difficult to imagine – it’s almost possible to think of inviting the river for tea. Still, it is a river, one of Mother Nature’s creatures. This might explain why, in Grand Valley, keeping a wary eye on the river every spring is still a community habit.

Grand river, grand benefits

In the mid-19th century, when Grand Valley was known as Joice’s Corners – also Luther Village and Little Toronto for a while, acquiring its current name in the 1880s – the river was a commercial neighbour. In 1870, for example, more than 5,000 logs cut in Amaranth alone were floated down to Lake Erie.

Though this benefit was significant, it pales next to the value offered today by the regulated flow of the river with its two crucial reservoirs and dams. The water level in the Grand drops dramatically in summer – in 1936 it dried up completely between Dundalk and Fergus – and this once limited the growth of riverside communities through lack of sewage facilities and drinking water. The Luther and Shand dams became the solution. (An alternative proposal, considered briefly, was an irrigation canal from Georgian Bay through Luther Marsh to the Grand.) The water flow and capacity managed by the Grand River Conservation Authority today has once again made the river the commercial neighbour it was years ago.

Management of the Grand’s watershed also offers major recreation benefits. While life beside an Ontario river has always offered wonderfully simple pleasures, such as catching tadpoles in summer and skating in winter, the Grand today has even greater attractions. Wildlife in the Luther Marsh and boating on Belwood Lake are obvious examples. Downstream, especially below Elora and Fergus, canoeing and rafting are major tourism incentives, while upstream the Grand has been listed by Canadian Fly Fisher magazine as the top stream in the province for brown and rainbow trout. Entertainment on the river has come a long way from the days when children in Grand Valley were let out of school to watch ice dams being blown up with dynamite.

No way to treat a neighbour

In 1937 Maclean’s magazine called the Grand River an “open sewer.” The people of these hills must have winced at that, even though the criticism was directed mostly at downstream communities such as Kitchener, where a 1934 report described the sewage dumped into the Grand as the “strongest in Canada.”

Still, the neighbours of the Upper Grand were not innocent of environmental sin, for when the Grand Valley Conservation Authority was formed in 1948, its studies of the deforestation, agricultural runoff and “dumping” from Fergus to Dundalk shocked the entire province.

The gradual return of the Grand River to a pristine state is an environmental good news story. More than 28 million trees have been planted in the watershed, and 82 species of fish – nearly half the number of freshwater species found in Canada – now thrive in its waters. In Luther Marsh, more than 240 bird species have been recorded. Among these are once-absent ospreys and bald eagles, which have returned.

But a watchful eye must never close. In 2013, for example, a study by Environment Canada and the University of Waterloo found that, in the Grand, concentrations of artificial sweeteners, which pass unaltered through both the human body and sewage systems, are the highest found so far in any of the world’s surface water bodies.

More Info

Grand River Facts

- The Grand River watershed covers an area approximately the size of Prince Edward Island and is managed by the Grand River Conservation Authority, the oldest water management authority in Canada.

- Southern Ontario’s longest river stretches 280 km. It ranks No. 4 in the province behind the Ottawa, St. Lawrence and Albany.

- Farms today take up about 70 per cent of the watershed while cities, towns and villages occupy about 5 per cent. Twenty-one conservation areas are located in the watershed.

- The Grand River rises in the Dufferin Highlands near Dundalk at a height of 525 m above sea level and enters Lake Erie by Port Maitland at a height of 174 m. Along its route it acquires four major tributaries, the Speed, Conestoga, Nith and Eramosa rivers, each of which has a history of significant flooding.

Related Stories

Hurricane Hazel’s Place in Headwaters’ History

Sep 18, 2018 | | Historic HillsWhen Hurricane Hazel finally blew itself out in October 1954, the damage and casualties left behind made it Ontario’s biggest weather event of the century. The flood control plans that followed were even bigger.

Big Weather

Jun 18, 2009 | | EnvironmentHold on to your hats! The weather, she-is-a-changing. Global warming is exacerbating Canada’s gloriously variable weather, adding a growing current of concern to our favourite topic of conversation. It’s been more than two decades since the “big tornado” hit these hills in 1985, but in recent years the incidence of smaller tornadoes, high winds and violent storms has escalated.

Rivers Run Through Us

Jun 20, 2016 | | Editor’s DeskWater springs up all around us in the streams and rivers and marshes and pools of the four major watersheds that sculpt our landscape and feed three Great Lakes.