Pure Tranquility. Sheer Glory.

In Amy Stewart’s Caledon garden, the soul of garden and gardener are one.

There are many ways to admire a garden and its gardener. But some gardens are so essentially themselves, strike such a perfect note of harmony, that mere admiration comes only upon later reflection.

In such gardens, it is not the rare exotic, the triumph of will over nature, that inspires awe. It isn’t the bold flourish or the tiny perfection. Nor even the sheer labour of it all. Moments spent in such gardens are moments of pure tranquility. Moments of sheer glory.

Amy Stewart’s garden in Caledon is such a garden. Though it is a large garden, it is filled with elements of secret and surprise. It is approached by a long driveway that winds from the main road past a tangle of sumach, descends over a low bridge where daffodils and bluebells bloom amid the marsh grass, then climbs again under a dark canopy of tall pines where it appears to end at a long, high stone wall. At the midpoint of that stern wall is a single wooden door. Beyond that door is another world.

The door in the wall opens into a foyer at the top of the Stewarts’ home. Beyond it, through the southern glass walls, Amy’s garden cascades down a sun-washed hillside, spilling into a wild meadow valley and a gleaming network of ponds before the forested hills rise in the distance.

Daffodils add a note of gaiety to the stone wall that forms the northern exposure of the Stewarts’ home. Photo by Rosemary Hasner / Black Dog Creative Arts.

When Clair and Amy Stewart conceived the north wall of their house, they were fully aware of the intriguing mystery that the long stone face would present to visitors. But that was not their only consideration. When they first purchased the large acreage in the 1950s, the only trees were in the steep ravines cut by a tributary of the Humber River. The rest of the high, cattle-grazed land was all but bald. The thick, windowless stone wall was a practical defence against the gale-force winds that swooped across the bare hills. It was a blend of inspired design and pragmatism that is characteristic of both Amy and Clair.

In those early days, Amy wasn’t interested in having a garden in the country. Although she was already a gardener, her attentions were lavished on her garden in Toronto. The Caledon farm was a weekend retreat for the Stewarts and their six children. They built a modest cottage and determined that wild nature would be allowed to flourish – though they helped the process along by planting thousands of trees. These included 100,000 red and white pine seedlings purchased for a cent apiece through the Ministry of Natural Resources and the Credit Valley Conservation Authority.

Those trees – pines, spruce, maples, oaks and larch – are now deep green forests that surround and protect the Stewarts’ home and garden.

It was not until 1975, when Amy and Clair were in their sixties and their children grown, that they sold their Toronto house and hired architect William Fleury to help them expand the Caledon cottage into a full-time residence. The result is a long, glass, wood and stone home that cups elegantly into the top of the hill.

It was not the inspiration of the flourishing trees or even the new house that launched Amy’s garden, but a small concession to a lawn. Because the hillside was so steep, Clair built a retaining wall to provide some flat land next to the house. He designed the wall with a prow pointing out to the valley. It would become the central axis of all that followed.

By Amy’s account that small patch of tended nature proved irresistible: “I thought, I’ll just plant a few flowers.” Asked about the evolution of her garden from that first small bed, her response is always the same, and always contains the same mix of modest self-amazement and absolute certainty: “It just grew.”

Peonies and irises are among the English garden favourites that flourish on the sunny and protected hillside. Photo by Rosemary Hasner / Black Dog Creative Arts.

It is the assessment of a gardener who is at one with her garden. For her there is no contradiction between the notion that the garden “just grew” and the hours, days and years that she has spent nurturing it. In the springs and summers from dawn to dusk. And likewise through the winters, which she spent in her greenhouse cultivating thousands of seeds.

Neither does her assessment belie the volumes of reading and the horticultural lectures that made her, among other things, easily fluent in botanical Latin. These are simply the tools of a master gardener. As is the knowledge she mined from other expert gardeners, among whom she especially credits local gardeners Liz Knowles, Brian Bixley and Jean deGruchy.

“I knew nothing when I started,” she insists. Except that she was a gardener.

“When I left home and planted my first petunia, I turned into a gardener.” (And was it really a humble petunia. “Oh, I’m sure it was,” she laughs.)

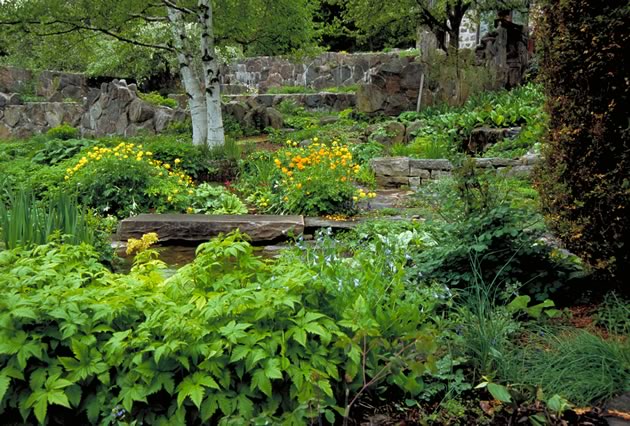

Clair has been her closest ally through all. He owned an industrial design company before his retirement and he is an avid artist. His strong æsthetic sense is revealed in the bones of the garden. After building the retaining wall, he went on to design the stone walls, the rock paths and stepping stones, the placement of boulders collected from the old farm fence lines, as well as the little rill that burbles from beneath one of those boulders, trips down the hill and pools in a small wetland where cultivated marsh plants thrive before the garden cedes fully back to meadow. (The water is actually piped under the house from the farm pond some 1,500 feet to the north.) All together, these elements provide the secure underpinnings for a riotous diversity of plant life.

For some thirty years, Amy and Clair have also been assisted in the garden by their farm manager, Jim Muir, and Theodore Henkenhaf. Jim has undertaken the heavier construction projects, acting as a kind of general contractor for the architecture of the garden. Theodore, an accomplished stonemason, has built most of the walls that enclose the garden.

But the plants have always been Amy’s. “I am the gardener,” she says. “I have had lots of expert help, but I am the gardener.” It is her spirit, labour and knowledge that infuse the garden with it unique vitality.

In her choice of plants, she has a bias toward the English cottage garden: peonies, irises, lilies, poppies, delphiniums and the like. And they bloom as abundantly on the Caledon hillside as in any Sussex lane.

Liz Knowles has been a frequent visitor to Amy’s garden over the past fifteen years. She describes Amy as a role model and generous mentor.

“The first few times I visited Amy’s garden, I must admit I came back depressed, wondering why I even bother,” Liz says. But that reaction was balanced by inspiration. “She allowed me to see what is possible here. You see all the pictures in the English gardening magazines and think we can’t do that. But there are things we can grow better here than in England, because we have the sunshine.” It was in Amy’s garden that Liz first realized that hellebores, that delightful staple of the English winter garden, can flourish quite happily in springtime Ontario.

For all the English influences, though, there is nothing of jealous colonial imitation about Amy’s garden. Among the distinctly Canadian granite boulders and escarpment limestone, Mediterranean plants rub shoulders amiably with their northern-bred neighbours.

“Rock paths and steps are softened with thymes, their scent mingling with the numbers of aromatic Mediterraneans which flourish,” wrote Allen Paterson, the director of Hamilton’s Royal Botanical Garden, in a 1985 article about the Stewart garden in the journal of Britain’s erudite Royal Horticultural Society. “Lavenders, santalinas, rues, winter savory. Local wisdom, splendidly disproved, says they won’t survive the winter.”

But the Mediterranean influence, too, has been absorbed and re-imagined in the distinctive context of the Caledon countryside. Native wildflowers, such as dame’s rocket, milkweed and goldenrod, mingle freely among the cultivated immigrants.

The charming garden ruin was constructed from materials moved from an ancient barn foundation elsewhere on the Stewart property. Photo by Rosemary Hasner / Black Dog Creative Arts.

Indeed, the garden’s most deliberate artifice has its roots deeps in rural Ontario culture. It is a ‘ruin,’ constructed after Amy and Clair visited a friend whose garden was enclosed in an old barn foundation. Smitten by the concept, Amy soon had her own barn foundation, designed by Clair and built with materials transported from an ancient barn elsewhere on the property.

At the time, Amy and Clair defended their fit of romantic whimsy by declaring that the structure would provide a protected enclosure for tender plants, and keep the groundhogs at bay. The foundation does offer a microclimate of sorts, but the groundhogs continued to feast happily. (It was the return of the coyotes that finally defeated them.)

Today the barn foundation needs no justification, swathed in clematis vines and dappled with lichens, it has settled firmly and naturally into the gardenscape.

Amy does admit to one failed attempt at cultural adaptation. On a trip to Japan, she became enamoured with the distinctive moss gardens of Kyoto. “I came home and I was determined to have a moss garden. I tried for years to get mosses to grow but, of course, you can’t grow moss in this climate. It grows where it wants to, and when it does grow I really encourage it, but you can’t force it.”

An accomplished plantswoman, Amy has experimented with thousands of plants, many of them tended from seed in her greenhouse. Still, she attributes much of her success to the garden’s protected southern exposure and well-drained soil. She insists that for all its diversity, her garden comprises only what will grow happily in it. She refuses to coddle her plants. “I’m not interested in things that are hard to grow, because they usually die. I’m not a specialized gardener. I’m interested in general effects. I just plant something and if I like it, I think, gosh, it would nice if there were a pool of it.”

And pools there are, and waves of colour and texture that yield to each other as seamlessly in their turn as the passing seasons.

The effect in sum is of a garden that is as truly unique as it is truly Canadian.

“It is not a showy garden,” Amy and Clair modestly wrote in Nicole Eaton’s and Hilary Weston’s book, In a Canadian Garden. “There are no perennial borders, nor, with the exceptions of May when the hills are yellow with daffodils and September when the goldenrod takes over, are there great drifts of colour to excite the imagination. This is a casual country garden with a collection of plants that interest us. Its beauty depends to a large extent on the natural contours of the valley embraced by the forest; its strength lies in the central axis that draw the eye to the distant ponds.”

A casual country garden it may appear, but Liz Knowles is in good company when she describes it as “one of the great Canadian gardens.”

Yellow and orange globe flowers (Trollius) cheerfully drop their petals among the stone paths. Photo by Rosemary Hasner / Black Dog Creative Arts.

Amy and Clair are now in their nineties. Over the past several years they have reduced the scope of the garden, returning far beds to meadow and woods. In the process the garden seems to have wrapped itself closer to the house as naturally as it once expanded.

Like the garden, Amy and Clair remain gracious, lively and welcoming. However, Amy’s eyesight has begun to fail. Though she can still make her way around the garden paths she knows so well, she can no longer fully enjoy the fruits of her labour.

Now, she looks to the future of her garden with the same pragmatism that has marked her life within it. “When I go the garden goes,” she says.

For her, garden and gardener are inseparable. Although she has shared it generously over the years, it has been, above all, an act of self-fulfillment. “I did it for myself totally,” she says. “I couldn’t stop gardening. There’s no explaining it.”