Two Little Railways Made North American History

The Toronto Grey & Bruce and the Toronto & Nipissing Railways were the first of their kind on the continent.

When he retired as chief engineer at the Pickering ‘A’ Nuclear Station, Rod Clarke decided to put a lifelong fascination with narrow gauge railways and fifteen years of research into a book. Narrow Gauge Through the Bush was the impressive result. Like so many boys, Rod Clarke always wanted to be an engineer. His first inspiration was a wind-up model train engine that his parents gave him when he was four. What’s more, he lived in a mining village in England’s industrial South Yorkshire and was never far from the heavy metal sounds and power of steam trains. But unlike most other boys, he took the next step.

At the age of 16, Clarke applied at British Railways in Doncaster to begin the training that would allow him to sit up high in the engine with one elbow out the open window and a hand on the throttle, in control of fire and steam. Unfortunately, however, the starting pay of three pounds a week would not even cover his room and board. So he decided to stay in school.

When Clarke and his wife Marie arrived in Canada in 1966, he was an engineer – but of a totally different sort. He had graduated as a trade instrument and control engineer and his work in Great Britain covered a broad spectrum from nuclear generator control room gauges to cockpit instruments in the Concorde SST.

In Canada, Clarke worked for Ontario Hydro and on his frequent trips from head office in Toronto to the Bruce nuclear generating station on Lake Huron, he would drive through Caledon and Dufferin. “I made the trip so often, I’d try to find different ways of going,” he says. One trip was an experience many will find familiar.

It took about an hour to get to Orangeville from Toronto one cold, clear winter’s night. But the trip to Arthur took three more hours because the northwest wind was hurling snow across the highway. Not every trip was so frightening. “I saw a huge amount of the country that the Toronto Grey & Bruce rail lines travelled through.”

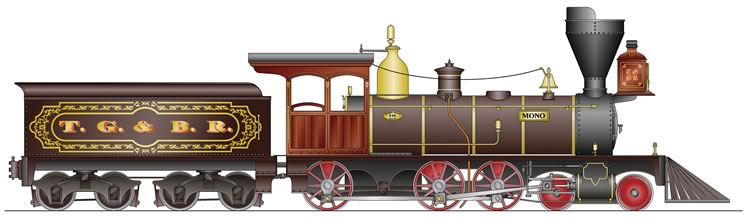

A scale drawing of the “Mono” by author Rod Clarke, who included several such drawings of locomotives in his book.

Clarke’s interest in railways had never waned. In his teens he had discovered the Lynton and Barnstaple Railway, a narrow gauge line in southwestern England and he liked the Lilliputian trains. The tracks on this line are just two feet apart, compared to today’s standard in North America, which is more than twice that wide.

In Canada, another narrow gauge railway caught his attention. He discovered a book by the chief archivist of the Canadian Pacific Railway – Omer Lavallée – and found a short reference to the Toronto Grey & Bruce and the Toronto & Nipissing railways, the very first narrow gauge railways in North America.

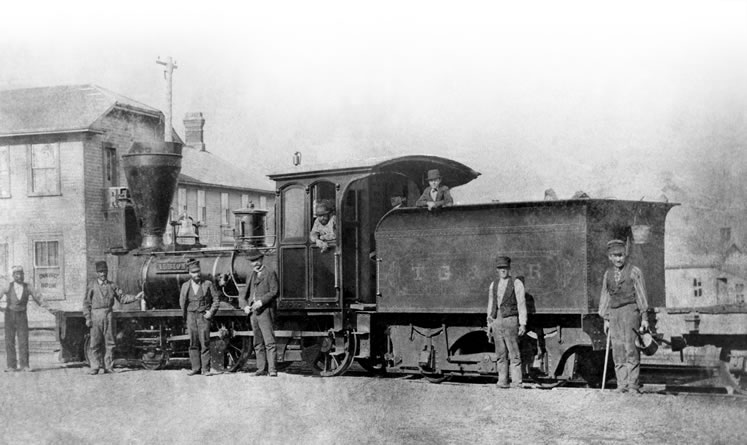

The TG&BR “Albion” was a diminutive, 15-ton locomotive that ran 19,840 miles in 1880. She is shown here at Orangeville in the mid-1870s, with several yard staff. The railways named their locomotives for directors and shareholders, as well as for the townships that contributed to building the railways: along with the “Albion” and “Mono” there were also the “Orangeville” and “Caledon.”

The trigger for his book was a visit to a hobby shop in Peterborough, Ontario. He was looking at the model trains and asked about scale drawings of narrow gauge engines. The proprietor knew about the White Pass Line in the Yukon and another that is still running in Colorado, but he had never heard of the Toronto & Nipissing that once chugged right through the Peterborough area. These two little railways had changed the face of Ontario in the late nineteenth century, yet few people knew they ever existed. Clarke decided the stories needed to be told.

He started with a booklet of scale drawings of the TG&B and T&N trains. Clarke had studied drafting and enjoyed building scale models, “I have always been interested in small mechanisms… but the first step is a scale drawing and I couldn’t find any.”

The curious engine on the cover of Narrow Gauge Through the Bush is no fanciful artists’ rendering. The T&N’s two-way Fairlie “Shedden” (and TG&B’s very similar “Caledon”) was a feat of marvellous engineering. The six drive wheels were powered by a long single boiler with two fires. Not only was it powerful, the engine’s two undercarriages were articulated. They could swivel under the boiler so the engine could get around sharp turns. The ball joints used in the original design are used in similar engines built today, despite the fact that the technology is 150 years old. They are cheaper and just as effective as modern high-pressure hoses.

His on-line research took him to places one would hardly expect to find anything about Ontario trains, including the Smithsonian, Southern Methodist University, and the Institute of Mechanical Engineers in England.

In Norway, he found a reprint of the diary of Carl Abraham Pihl, an engineer who had helped build narrow gauge railways in Norway and who provided technical advice for the Ontario projects as well.

Pihl’s diary of his 1871 trip to Canada to attend the opening of the narrow gauge lines was written in English and Norwegian.

“I picked up a Norwegian dictionary and learned a bit of grammar to translate it,” Clarke says. He also learned to decipher the microfiche of handwritten notes from English engineer Edmund Wragge who was another guiding light in the design and construction of the two lines.

Narrow gauge railways have some significant advantages, particularly in rough and hilly or mountainous countryside. The tracks of the TG&B were just three feet six inches apart, compared to the standard four feet eight-and-one-half inches. They’re cheaper to build. Not only is the right of way narrower, the trains can negotiate much sharper turns, which makes them easier to manoeuver around obstructions and negotiate steep grades.

The engines are marvels of engineering. The “Shedden,” the T&N double-ended engine that appears on the cover of Clarke’s book, is of a type that is still being built by a narrow gauge tourist line in Wales. The TG&B had a very similar engine called the “Caledon.” Today’s models, however, are oil fired rather than wood to prevent sparks. The cone shaped stack on wood-burning engines housed a screen to keep burning bits from floating into the nearby woods.

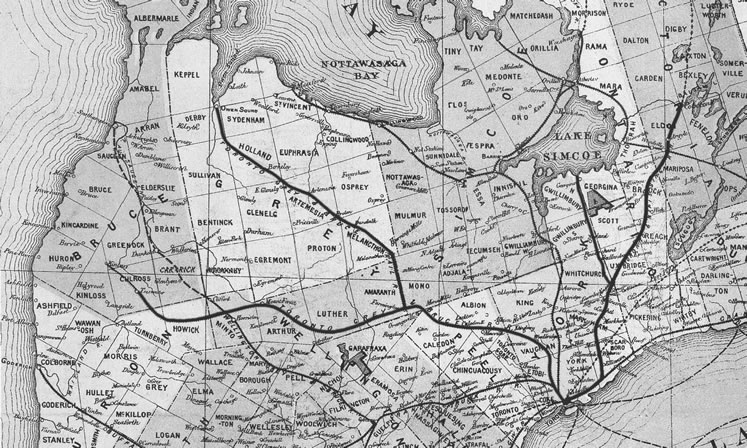

The Toronto Grey & Bruce connected Toronto to Owen Sound with a branch that headed toward Lake Huron but made it only as far as Teeswater. The Toronto & Nipissing line went from Toronto to Coboconk with a connection from Stouffville to Sutton. They carried passengers, freight, timber, farm produce and mail to and from Toronto.

The Toronto Grey and Bruce, Toronto and Nipissing, and Lake Simcoe Junction Railways as built, 1877. Adapted from a map of the Province of Ontario by James Campbell & Son of Toronto, 1874. Note that the original map shows a TG&BR extension from Teeswater to Kinloss which was never built. (Archives of Ontario)

The 392-page, coffee-table-format book includes an extraordinary breadth of detail aimed straight at what Clarke affectionately calls “railway nerds” (he counts himself among them), but it is also a social history about the people who financed and ran the railways, the trials of construction that saw many workers killed, the townspeople who welcomed or decried the train’s arrival, and the farmers whose wooded back lots were cleared to make way. Their stories are told not only in words but also through extensive photographs, maps, advertisements, and other archival documents of the times, as well as scale drawings.

Now that the book is finished, Rod Clarke will be able to focus more attention on his scale models. He thinks sometime soon he may set aside the electric-powered engines and try building one with a working steam engine.

WHEN MONO RACED ACROSS PROVINCE, BREAKING RECORD

Old Railroaders to This Day Talk of Great Run to Georgian Bay

— TRIP WAS SORT OF OFFICIAL SECRET —

Some People Disposed to Doubt Story, But Many Believe it True

WHY THE TRIP WAS MADE

Engine Ran Without Any Cars Behind and Took Wood Only Once

“It was in August 1876,” said the old driver, “that the superintendent came hurrying over to the roundhouse and said, Davy [probably Driver David B. Weekes] we’ve got to get these freight records through to Owen Sound by four o’clock. The ‘Africa’ (I think that was the vessel named) sails at four and she has got to have these papers or there is going to be a mix-up that the freight department can’t sort out in a century.”

“All right, sir,” said Davy, “I’m wooded up and she’s carrying 180 [psi], If I can get to Shelburne without wooding-up we’ll make it.”

In the picturesque language of the ‘road’ the old engineer went on to tell how David climbed up into the cab, caught the bundle of manifests tossed to him by the superintendent, opened the throttle, and started the greatest race against time in the history of the division.

Little by little the engineer opened the throttle wider and with each motion the ‘Mono’ leaped forward with a new speed impulse. As she tore along across the fields and through the forest cuttings the engine rocked from side to side, threatening every second to throw herself from the forty pound rails. The engineer’s face became tense and white as he fixed his eyes on the track ahead. Farmers stood in the fields and gaped in open-mouthed amazement for the locomotive and its driver looked like wild things bent on self-destruction. Near Woodbridge the ‘Mono’ dashed over the high wooden trestle with a clang and rumble of metal that could be heard for miles. Like a dart she sped to the foot of Caledon mountain and commenced her laboured climb up the grade. Gathering speed and with exhaust spitting fitfully she hit the horseshoe curve and, as the old engineer said quaintly, “Went around it on two wheels.” The run down the slope [sic] to Caledon and Orangeville was daring beyond credence. It was the supreme test of courage for a locomotive driver with a duty to perform. The snapping of a piston rod or the loosening of a bolt meant destruction and death.

The driver had supreme confidence in the ‘Mono’ and as for himself he never gave a thought.

North of Orangeville another nasty grade was climbed, but the engine was steaming splendidly and they pulled up to the woodpile at Shelburne on time. A dozen men were waiting to load the tender with selected well-dried maple. David, the engineer, and the fireman climbed back into the cab and waved goodbye. The cheers that came back to them were scarcely audible because of the noise of the exhaust. The ‘Mono’ was under way again. David glanced at his watch. It was 2:30 pm, but the worst half of the road had been covered. He had ninety minutes to make sixty miles and he believed he could do it. The fireman, stripped to the waist, was wet with perspiration, but his eyes danced with the spirit of the race.

Rail fences, poles, and patches of forest flashed by, and some of the curves were swung with a momentum that almost threw the driver from his seat. Men and women working in the fields waved their hands and shouted. Cattle and horses, with animal terror in their eyes, ran fast to escape the mysterious monster. At last the engine rose over the crest of the long straight downgrade that runs through Markdale. The station agent shoved back some people who had gathered on the platform, just in time, for the ‘Mono’ hurled herself through the place, some people declare, at seventy miles an hour. The suction might have drawn the people on the platform under the wheels. Holland Centre and Chatsworth, little hamlets in 1876 were passed so quickly that only the clatter of the switch points indicated the astonishing progress. The engineer glanced at his watch as the St. Vincent crossing flicked past. The time was 3:40 pm and he had twenty minutes to cover less than five miles.

Since that day no locomotive has sped down the grade at Murray’s Cut with such reckless speed. Even the engineer began to feel a thrill of uncertainty. Could he stop the engine before he reached the end of steel? Four hundred yards ahead was Boyd’s wharf and a hundred yards beyond that was the end of the line. Slowly David shoved over the throttle.

With the instinct of the trained engineer, he was conscious of a slight response, and it gave him confidence. Again the throttle moved and again speed slackened. Then he threw ‘her’ right over. The fireman rang the bell vigorously and great clouds of escaping steam almost enveloped the ‘Mono’ as she came to a standstill at her destination with a record that may never again be equaled on the division. The engineer looked at his watch. It was 3:48 pm and the distance, 122 miles, had been covered in two hours and forty-eight minutes. Out at the end of the wharf the steamer ‘Africa’ was waiting. The purser with a bundle of manifests hurried aboard, the lines were cast off, the captain sounded the engine room bells, and she sailed for the north ON TIME.

J.S.C.; ‘When ‘Mono’ raced across Province;’ The Star, Toronto; March 28th, 1914.