Bad Night on Caledon Mountain

On a cold, dark November night in 1941, just when the war news from Europe was bleaker than ever, a fatal plane crash in Caledon Township showed that even training for war was perilous.

The noise over Canada began in earnest in the spring of 1940. That was when the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan kicked into high gear. It was a plan that turned Canada into a worldwide training camp for Allied air crews. For the next five years the country echoed from coast to coast with the powerful drone of unmuffled engines overhead.

The skies above Caledon Township were busier than most. Situated as it was with Camp Borden to the northeast, Malton on its southern edge and the Mount Hope training school to the west at Hamilton, Caledon was criss-crossed night and day by hundreds of warplanes and trainers.

In a rural township where the sound of a single aircraft had once brought whole families running out of houses and barns to gaze in fascination, the sound of multiple engines soon became so ordinary, so much a part of life during “The War,” that as early as 1941 entire formations could pass over and barely attract an upward glance.

Strange Noises at Midnight

What did make people sit up and take notice was when something about the noise changed – and that was precisely what twigged the attention of Marjorie and Helen Cluff on the night of November 12, 1941. Just before midnight they heard the twin engines of an Avro Anson bomber pass over their farm off Highway 10 south of Caledon Village.

They might not have been able to identify it as an Anson. That kind of recognition was something thirteen-year-old boys like Fred Bull were good at, but Fred was at home over on the 2nd Line East, sound asleep.

Had he been home, Art Bracken, a man in his late twenties, probably could have distinguished the sound of an Anson from, say, a Halifax or a Stirling or certainly a Harvard Trainer, but Art had dropped into the Sutton House in Caledon and did not hear the plane pass over.

Both Art and Fred would become part of the drama later on, but for the moment the Cluff sisters were among the first on the ground to realize the Anson was in trouble.

For one thing, it was flying way too low. Although night training flights were common, they usually took place at higher altitudes, especially, for obvious reasons, over the Niagara Escarpment.

“It was circling,” Marjorie told the Toronto Star the next day, something unusual enough to prompt the sisters to get up for a look. But they didn’t even make it outside. “I was standing right by the door when the plane came swooping over,” she said.

It must have been an agonizing moment for the Cluffs because they had lived much of their lives by the escarpment and knew that at such low altitude in the direction it was heading, the aircraft was doomed unless it could make an instant, steep climb.

According to Fred Bull who visited the crash site in daylight the following morning, “a steep climb” was indeed attempted by the pilot at the last moment, but it was too late.

From her doorway Marjorie Cluff saw the flash of the plane between the trees as it headed toward Caledon Mountain. “Seconds later it crashed,” she said. “It must have happened about 12:15.” (The official inquiry gave the crash time as 12:10.)

A Search Party Goes Out

It’s possible that other families near the northeast corner of the present-day intersection of Willoughby Road and Escarpment Sideroad in Caledon saw the plane or heard the crash, but the Cluffs had a telephone, so were able to raise an alarm.

“It was after three in the morning before we got up there and found them,” remembers Art Bracken, now ninety-five years old. “Speers came into the hotel in Caledon – he was the nighttime telephone operator – and said the Cluff girls told him they saw a plane go down somewhere over by 10 Sideroad. He said he had trouble getting people on the telephone at that time of night to organize a search party. That’s probably why he came to the hotel. So we got some lanterns, a couple had flashlights, and away we went.”

Art was the first to arrive at the site, even though the search party had expanded by that time to include men like Russ Forbes, the township road foreman, and Syd Walders, who worked for the CPR. Peel County’s High Constable, Ray Hodgson had come in from Brampton and by then, local farmers too had joined in. Still, the downed aircraft was not easy to find.

“You have to realize, the bush was thicker in those days,” Art Bracken recounts, “and it was pitch black up there, just as dark as it can be. From the top of the mountain you could see the Toronto lights but they didn’t help any. And there was no hydro then on a lot of the farms. Believe me, it was real dark.”

And Fred Bull notes that the roads in the area were nothing like today’s thoroughfares. “You sure couldn’t speed along,” he says. “Sometimes the sideroads weren’t much more than a track, especially near the mountain. If you lived in that part of Caledon then it was easy to understand why it took those fellows a while to get to the plane.”

By three a.m. the search party had focussed in on the property of bachelor farmer Frank Johnston, and worked its way up the Caledon Mountain. Once there, it was a voice that led Art Bracken to the scene.

“I heard someone calling out,” Art remembers, “and some banging and a few minutes later there it was. The first man I came upon was this poor fellow about fifty or sixty feet from the plane. He must have been thrown clear, or else he crawled out, but I don’t think so for he was hurt so bad. He died there in my arms.”

The flier whom Art had tried to comfort was one of three men to die that night in a crew of five. According to Robert Johnson, a local farmer and member of the search party, the shouting Art Bracken had heard came from one of the two survivors. Both of them were inside the wreckage, one of them gravely injured and immobilized underneath one of his dead comrades.

The third victim, already dead when the searchers arrived, was on the ground outside the plane about twenty feet away. The two men who made it were the pilot and the wireless operator. Badly injured, both were moved with great difficulty down the mountain and on to Peel Memorial Hospital.

In a twist of sad irony, the three crewmen who died in this airplane that crashed because it had lost its way and was flying too low were all training to be navigators.

On Site the Next Day

Caledon farmer Art Bracken, now 95, was the first to arrive at the crash site on Lot 11, Conc 1 WHS on that tragic night in 1941. “It was after three in the morning before we got up there and found them,” he recalls. One of the crewmen died in his arms. Photo Courtesy Fay McCrea.

By dusk of that day, November 13, the accident scene was fenced off and the RAF had posted guards to keep curiosity seekers away. (Both the Anson and its crew were RAF out of the flying school at Mount Hope, not RCAF.) Before that could happen, however, a group of unusual and very observant witnesses had paid an unhindered visit to the site.

When Fred Bull and his schoolmates arrived at one-room S.S. #18 that morning, a few concessions east of the crash, they soon found themselves embarking on a field trip not many school kids have ever experienced. Their teacher, Miss Walker, loaded the entire school population – all eleven of them – into her car and drove over to the crash site. Her students were going to see history first hand.

For Fred Bull, now 80, the experience made a deep and indelible impression. “I can see it like it was almost yesterday,” he says. “Nobody said ‘stop’ or ‘don’t go there’; we just walked right up to it. There was blood on the ground, airplane parts and bits of metal everywhere, wings sheared right off …”

Fred’s recollection of the crash site and what must have been the sequence of events at the time of the disaster, confirms accounts offered by other key people in the story. He noted where the Anson had clipped the tops of trees (as did Art Bracken and others) before crashing farther up the mountain.

“You could see the poor guy was trying to pull up after hitting the trees because even though the plane hit into the brow of the hill, it was a kind of belly landing too, like he was trying to gain altitude. It’s sad really. He was so close to clearing that mountain. When you looked at things from the ground beside the plane, it seemed another ten-twenty feet higher and he’d have made it!”

How Did it Happen?

Thirteen aircraft took off from the Air Navigation School at Mount Hope around 11 p.m. on the night of November 12. One of them was the ill-fated Anson Mk I. The purpose was a routine night-training flight that was to take the planes southwest over Chatham, then north over Parkhill, and east back to Mount Hope again.

Thus, the inevitable question: With a flight plan entirely south and southwest of Mount Hope, what was the Anson doing over Caledon, which is not only northeast of Mount Hope but entirely in the opposite direction from the flight plan?

How had the pilot and crew had become so hopelessly lost? According to one newspaper report, there was snow and limited visibility that night, causing flights out of Malton (but not Mount Hope) to be cancelled. Yet Art Bracken remembers only that it was dry but cloudy, making the night very dark, and he said so in his witness testimony to the RAF inquiry.

The Cluff sisters’ testimony was similar, both emphasizing that there was neither rain nor snow, adding that from their farm at the foot of Caledon Mountain they could easily see the Anson as it approached the top.

Further, the commander at Mount Hope reported flying conditions as “fair” that night and that cloud over London at takeoff time was expected to clear. However, according to the testimony of the pilot, Flight Lieutenant McDowell, there was dense cloud cover (a condition attested to by other pilots in the air at the time, one of whom made an emergency landing at London) and it was because of the cloud that he became lost.

Once lost, the Anson flight underwent a tragic and relentless chain of circumstances. To begin with, the three trainee navigators were unable to come up with an emergency alternate flight plan. A former RCAF navigator, Bob Kensett, who trained at Malton before serving in Europe with Bomber Command and who remembers the Anson well, has studied reports of the crash. He notes that as trainees, the three navigators aboard had likely not yet been taught all the navigation aids. In any case, he adds, “on the Anson, the aids were woefully inadequate.”

Kensett says that normally the wireless operator would have radioed for homing bearings, and the official inquiry noted that LAC Higham, the wireless man on board, did so twice. Yet the fact the inquiry recommended closer co-operation between pilot and wireless operator suggests that in the case of the Anson crew that night, such co-operation may not have occurred.

Even so, the crash still might have been avoided had just one of the doomed crew been an “Ontario boy.” It appears the pilot resorted to visual reckoning and made the fatal determination that the city lights he could see below belonged to Buffalo, when in fact they belonged to Toronto.

Someone local might have been able to correct the pilot, but four of the crewmen were fresh from England and the fifth, a Canadian (although reported to be British) was from Vancouver.

Having assumed Buffalo as his reference point, the pilot would naturally have thought he was over flat ground – or Lake Ontario – and deemed his altitude (1,200 feet) adequate. But the Anson was circling northwest of Toronto, not northeast of Buffalo, making a collision with Caledon Mountain (c.1,400 feet) almost inevitable.

Fred Bull didn’t go back to the site again. Nor did Art Bracken or Robert Johnson or Russ Forbes or any of the search party. With the area closed off there was no point. But while restricted access was to be expected, what is curious was the speed with which this serious air accident disappeared from public comment.

Both the Toronto Star and Globe carried a small follow-up the next day (including an erroneous report that one of the survivors had died; no correction was published even though the “dead” wireless operator was in hospital on Toronto’s Christie Street for more than two years). The Brampton Conservator ran no follow-up, although Peel’s coroner, Dr. W.H. Brydon, had much to say in the first spate of reporting. And the Orangeville Banner, which had a whole week to put the story together, did little more than repeat the Star’s account. Then, nothing.

Why the instant blackout, even in the local papers? One reason was that the Allies had their collective backs against the wall in 1941 and the media had their pages full with bigger – and gloomier – war news. Germany controlled the Atlantic with its submarines and much of Europe with its army. Rommel was still on top in Africa and Britain itself was bracing for invasion.

On November 14, the day after the crash, the War Ministry announced that a German sub had sunk HMS Ark Royal, the third British aircraft carrier to go down since 1939. And if that was not enough, a flotilla of 140 warships from potentially hostile Japan had been spotted near Singapore. In the face of continuing news like that, a plane crash in remote Caledon was unlikely to inspire much coverage.

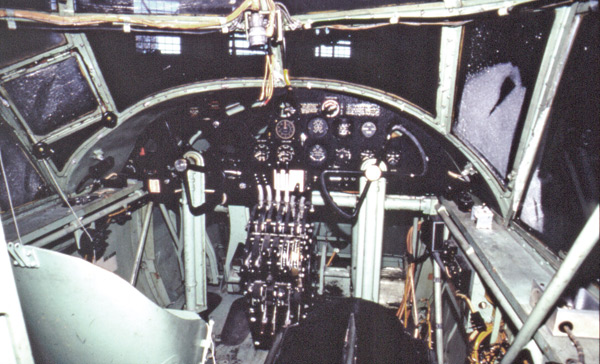

The Canadian-made Avro Anson as used almost exclusively for training during the World War II. Photo Courtesy Canada Aviation Museum Ottawa.

And that was just the global picture. At home, the news was also bad and far more personal. In the week the Anson hit Caledon Mountain, the RCAF released an updated casualty list. Three more Canadian airmen had died in Europe that week and four had been declared missing, bringing the combat total to 1,030 while three more died in training accidents in Canada. To an already war-weary readership, the sad death of three airmen who were not local, not even Canadian, didn’t seem to warrant a lot of ink.

Of course there was another powerful issue in play: the need to dilute any impression that the training of air crew in Canada, a wholesale, flat-out effort that regularly cut corners under pressure, had dangers all its own. (More than 800 airmen were killed in training here during the war.)

The fact that a flight out of the Mount Hope base got lost with three trainee navigators aboard, all of whom were killed in a crash in which human error factored heavily, was not likely to encourage enthusiasm for the Allies’ air training plan.

Caledon did not immediately turn its back on the victims, however. The township council instructed its clerk, Vernon Davison, to ask the Department of National Defence for permission to build a small cairn to commemorate the men who died. The Department replied that such recognition was officially in the hands of the War Graves Commission, but if the township wished to go ahead, there would be no objection.

There is no evidence though, either in local records or the public files in Ottawa, that further steps were taken. The cairn was never built. And so it was that the fatal end to a routine training flight over Caledon soon slipped from the public memory. In November, 1941, there was already enough sad remembrance to go around.

_________________________________

Ken Weber is grateful to Caledon historians, Margaret Foster and Fay McCrea, for their contribution to the research for this story.

The Crew

The three trainee navigators killed in the crash of the Avro Anson on Caledon Mountain were D. Donahue, D.A. Drayton and R.A. Gillman, all from England. They are buried in RAF plots in St. Paul’s Anglican Church cemetery in Mount Hope. (They rest in plots 1, 2, and 3, suggesting they may have been the first of Mount Hope’s fourteen training fatalities during the war.)

John Higham, also from England, was the wireless operator. He was the most seriously injured and spent two and a half years under medical treatment; he was honourably discharged in August, 1944, and used crutches for the rest of his life. He died in 1987.

The pilot, Alexander McDowell, at the time reported to be British but actually a Canadian serving with the RAF, was the least injured and returned to duty not long after the crash. He became a Squadron Leader with Bomber Command and, on October 22, 1943, was shot down over Germany. He is buried in the Rheinberg War Cemetery.

The Avro Anson a.k.a.“Faithful Annie”

Pilots generally liked the Anson, hence the positive nickname. (The famous Harvard Trainer, on the other hand, was often dubbed “The Yellow Peril.”)

Of the more than 16,ooo airplanes Canada produced and delivered to the Allied forces in World War II, 2,882 were Avro Ansons, most of them manufactured in Montreal and in Amherst, Nova Scotia, although the Avro plant at Malton is also credited with some production (as is the Cockshutt Plow Company of Brantford).

The model made in Canada was the Mk II. Its fuselage was made of plywood because steel was in the highest possible demand and the majority of these aircraft would be staying in Canada.

The Anson which hit Caledon Mountain was a previous-generation Mk I. Although it was designed in Britain as a twin-engine light bomber, the plane was used almost exclusively as a trainer throughout World War II. An incident on the second day of the war may have contributed to that decision.

While on patrol along the Scottish coast, an Anson crew spotted a submarine on the surface and dove low to bomb it – but the bomb bounced off the water and exploded high in the air, hitting the Anson instead! The downed crewmen were rescued by the submarine. Somewhat reluctantly perhaps, for the sub they’d tried to bomb was British.

A Grandson Remembers

When wireless operator John Higham (right) left Canada in 1944 after more than two years of treatment at “Christie,” Toronto’s much maligned and dilapidated veterans’ hospital and predecessor of Sunnybrook, he wrote the Globe and Mail to thank Canadians for their kindness during his long rehabilitation. The “Christie” is long gone and Caledon Township’s proposed cairn was never built, but Caledon Mountain, where the Anson met its fate in 1941, still dominates the horizon.

Higham never saw Canada again, but last year, his grandson, Simon Noble of Lancashire, England, wrote town officials seeking information about the crash that spared his grandfather. In doing so, he reopened a remarkable and largely forgotten page of Caledon history.

With the support of Heritage Caledon, Noble planned to visit the crash site this month, in a gesture that demonstrates after all that the memory of individual sacrifice is never truly lost.

During the Second World War, my mother lived on a farm near Bond Head, Ontario. She passed away in 2012. She kept an old cigar box with artifacts that she labelled: “Souvenir pieces of Avro Ansen Plane Crash, March 13, 1941. 2 planes collided-7 killed. Bond Head”. She would have been 17 at the time and apparently went to the crash site and collected these few things..a plastic dial, a button, some canvas and wood, and a brass plate with the following information: A.V. Roe & Co.Manchester and Hamble. Avro Type: Anson DWG No. G999 Serial No. R3LW38224 Date: 2/10/39

I have looked for news records of this crash but have been unable to find anything. If this is of interest to you, please let me know. Perhaps you know more about this incident. It certainly made an impression on her at the time…

Thank you Dale Midwood on behalf of Mary Midwood (Scott)

Dale Midwood on Nov 13, 2016 at 9:39 am |

To Dale Midwood:

The British Commonwealth Air Training Plan (BCATP) was an urgent and initially haphazard program rushed into existence and accidents in 1941 were quite frequent. There was, understandably, a great reluctance on the part of officials to report these to the media which, in any case, were preoccupied with the larger and more dramatic events occurring on the war front itself. Only a few days either side of March 13/41, London endured its worst bombing yet as did Glasgow; there was significant convoy loss in the Atlantic and England was excited at the passing of the lend-lease program by the US Congress. An embarrassing crash like that near Bond Head may not have attracted much media response if any.

Nevertheless, given that the crash occurred in Simcoe County, you may find reference in county newspapers archived at Simcoe County archives in Midhurst Ontario. (For example, a training crash near Grand Valley, Ontario, in May, 1941 was comprehensively reported by a local paper, the Grand Valley Star so Simcoe papers may have information you seek.) A second avenue of information would be available via the BCATP Museum in Brandon, Manitoba which may have a copy of the required investigation and report.

I hope this is of some help.

Sincerely,

Ken Weber (author of the article in In the Hills magazine to which you refer)

Ken Weber on Nov 20, 2016 at 4:35 pm |