Clara Brett Martin: Canada’s First Woman Lawyer

A Modest pioneer, Clara Brett Martin, the daughter of a Mono Township pioneer family, became a pioneer of a different sort when she challenged the Law Society of Upper Canada to become the first woman lawyer in the British Empire.

At the Martin family homestead settled in 1832 near Blount in Mono Township, books were a valued commodity. Reading was a prized skill; creative writing in legible penmanship was a requirement; and forays into the mysteries of calculus and Euclidean geometry were not only frequent but expected of the children: all twelve of them.

Because the Martins of Mono were highly literate, it is reasonable to assume they were familiar with Principles of Biology by the renowned scientist, Herbert Spencer. It was the gold standard of biological science in the nineteenth century. However, it is equally reasonable to assume that Clara, the youngest Martin, would have read this highly regarded publication with eyebrows arched, especially its “principle” that women are intellectually inferior to men and incapable of logical reasoning.

Spencer was merely lending authoritative expertise to what most men and women in the nineteenth century accepted as truth. But he also went on to reinforce a common response to this perceived deficiency in females: namely that educating them beyond the basics of reading and writing, with perhaps a nod to the gentler arts like music, was not only futile but counterproductive.

According to Spencer, advanced learning for women put the human race at risk because the “mental labour” required could make them infertile, a fact evident, he wrote, “not only in the earlier cessation of child bearing” among educated women, but also in the number of “flat-chested girls who survive their high-pressure education and are incompetent to [nurse babies].”

Clara was not intimidated

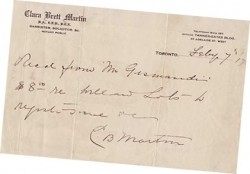

Clara Brett Martin, 1899. She described enduring “annoyances too petty to be put on record, but none the less real … the thousand ways that men can make a woman suffer who stands among them alone.” Image Courtesy Law Society of Upper Canada Archives (P291)

Whether or not Clara Brett Martin ever objected aloud to this conventional wisdom we will never know, for throughout her life she kept her opinions to herself. Her actions, however, spoke clearly. In 1888 she applied to Trinity College in Toronto, passed the entrance exams in the top percentiles, and two years later, on June 27, 1890, graduated with a Bachelor of Arts with high honours. She had just turned sixteen.

It could not have been an easy time for her. Trinity had only admitted its first female students in 1885, to profound hostility from male students and professorial staff. At the time Clara enrolled, Trinity’s syllabus actually advised female students that their attendance at lectures was not required! Those like Clara who ignored the hint were asked to sit apart in the classrooms.

Clara no doubt gave in to those prejudicial seating requirements. Although she was unwilling to accept an inferior role, symbolic disobedience was never her style. Instead she quietly took the paths that her intelligence and fierce determination laid out for her. At Trinity for example, she majored in mathematics, something practically unheard of for a female student, and her success must have shocked medical experts of the day.

Canada Lancet, the nation’s main medical journal, had long argued that the physical reality of blood flow to the brain militated against the possibility of females doing math because in women, “the blood supply is directed toward portions of the brain concerned with sensory functions.”

Yet here was young Clara Brett, a dramatic contradiction to the claim. Perhaps it was coincidence, but right around the time Clara graduated, an editorial in the Lancet offered the hope that these “withered, shrunken-shanked girls [who pursue further education] will always be a poor minority.”

Intelligent and courageous or just ‘a queer duck’?

Clara was anything but withered or shrunken-shanked, but she was certainly seen as different, even eccentric. “A queer duck” (often code for “feminist”), one of her fellow students called her; “a very odd sort of woman” was the phrase of another. That she must have seemed exceptional to those around her is a given, for with a math degree she had flown full in the face of accepted beliefs about women’s intellectual capacity. But Clara’s idiosyncrasies went even further. She rode a bicycle!

By 1900 what became known as the great “bicycle craze” was so solidly established that the sight of women “wheeling” was quite ordinary. But in the 1880s, even at a university, riding a bike made Clara unique. Adding to the fuss was that in order to ride a bicycle, women like Clara had to flout proper fashion, discarding the mandatory corset in favour of bloomers or the newly popular shirtwaist (a dress with a bodice tailored like a man’s shirt).

Interestingly, among the male students who thought her odd was one who noticed Clara had “the ability to wear a shirtwaist with distinction.”

Later when she had become a practising lawyer, newspapers often reported positively on her appearance. Clara was not unattractive, but if any man ever expressed a romantic interest there is no evidence of response from her, another possible reason for the view of her as “a queer duck.” Yet nothing in Clara Brett Martin’s pioneering journey stirred the flames of male chauvinism more than her decision to become a lawyer.

No women allowed

There is a deep irony in Clara’s 1891 letter to the Law Society of Upper Canada, expressing her wish to join its ranks. Quite naturally she assumed such a body would be the very guardian of equality and justice, so her letter appealed to the “broad spirit of liberality and fairness that characterizes members of the legal profession.” What she got from the keepers of liberality and fairness was a flat “no” – followed by a wave of gender bigotry in the legal press.

“It is rather a surprise,” mewed the Canada Law Journal, “to see a woman seeking a profession where she is bound to meet much that would offend the natural modesty of her sex.” The Western Law Times “shuddered to contemplate the results” if women became lawyers for soon they’d want to be judges or even sit on juries! Not to worry, assured prominent lawyer William Meredith, leader of the opposition in the Ontario legislature. Women, he told the House, would avoid the legal profession because their obsession with fashion meant they would be unwilling to wear the same official robes as men.

Over the six years it took Clara to become a lawyer, such comments were continually dumped in her direction. None of them ever dealt with her gifted mind, her achievements or her determination. Even on the day she made history by being called to the bar, the Toronto Telegram simply noted that she “wore a black gown over a black dress … and bore her honours modestly.” Only the Montreal Witness that day paid tribute to her “strong sincerity, indomitable perseverance, and splendid brain.”

Had the august leaders of the Law Society paid more attention to those characteristics six years before, they might have avoided an embarrassing defeat.

Power, persistence, and the pulling of strings

Clara Brett Martin was not the daughter of simple farmer folk who settled in Mono Township. The Martins had influence and connections. Clara’s mother’s family, the Bretts, had even more. Thus Clara was unabashed about seeking help when she needed it, and she was not shy about knocking on doors that she knew would be opened. So when the Law Society first turned her down, she promptly recruited Ontario’s premier Oliver Mowat to her cause.

Clara Brett Martin was not the daughter of simple farmer folk who settled in Mono Township. The Martins had influence and connections. Clara’s mother’s family, the Bretts, had even more. Thus Clara was unabashed about seeking help when she needed it, and she was not shy about knocking on doors that she knew would be opened. So when the Law Society first turned her down, she promptly recruited Ontario’s premier Oliver Mowat to her cause.

Mowat was no feminist – he once said publicly that, “In most cases a woman has no history apart from her husband” – but he was a consummate politician and in the “New Woman Era” of the 1890s, he could feel the winds of change. Pulled into the fray by Clara, he became her champion and in 1892 convinced the legislature to pass a bill that gave the Law Society the right, but not the obligation, to admit women as solicitors.

When the society responded that it was “inexpedient” to do so, Mowat pushed again; the lawyers relented and in 1893, Clara registered as a student-at-law. She landed a plum articling position with a firm headed by Sir William Mulock (his daughter was Clara’s close friend), but was so harassed by male students she had to switch firms.

After bringing some of the most powerful figures in Canada to her side in taking on the hidebound Law Society of Upper Canada – and she was still just nineteen – this must have been a low point for Clara. In a rare interview given years later she described enduring “annoyances too petty to be put on the record, but none the less real … the thousand ways that men can make a woman suffer who stands among them alone.”

Nevertheless, Clara completed her articling and quite possibly enjoyed a touch of vengeful satisfaction when she beat every single male student in the annual examinations. Still, success was not complete. She was eligible to be a solicitor now, but to appear in court she had to become a barrister as well, a designation controlled by the Law Society and an issue not included in Mowat’s legislation five years before. Clara duly applied and – no surprise – the Law Society again said “no.”

So Clara pulled some more strings. She turned to the newly formed Council of Women, got enthusiastic support from Lady Aberdeen, the activist wife of Canada’s Governor General, rounded up other successful trailblazers, such as Dr. Emily Stowe (the first Canadian woman to attain a medical degree), and re-enlisted Oliver Mowat.

So Clara pulled some more strings. She turned to the newly formed Council of Women, got enthusiastic support from Lady Aberdeen, the activist wife of Canada’s Governor General, rounded up other successful trailblazers, such as Dr. Emily Stowe (the first Canadian woman to attain a medical degree), and re-enlisted Oliver Mowat.

Once again, the premier pushed a bill through the legislature and once again the Law Society resisted. Eventually, after a last minute hissy fit over what women lawyers should wear in court, the society backed down and, on February 2, 1897, Clara Brett Martin became a fully fledged solicitor and barrister, and the first woman lawyer in Canada, indeed the first woman lawyer in the British Empire.

Worth the struggle?

On February 3, 1897, the day following her call to the bar, a tiny ad appeared in the Toronto Telegram: “Miss Clara Brett Martin desires a position in a law firm where experience can be had in practical work, that being the object rather than salary.”

There were no ads from graduating male students that day. Neither of the firms where she had articled would hire her, but a small two-man firm took her on and, by 1901, the name “Martin” was added to that firm’s letterhead. In 1906 Clara established her own firm on Toronto’s Bay Street which she ran successfully until, sadly, she died of a heart attack on October 30, 1923, at age 49.

Because she was intensely private and very much a subscriber to the Victorian notion that overt public displays were vulgar, Clara’s deep-down thoughts were never revealed. Not by her, nor by her sister, Fanny, with whom she lived quietly for years.

Clara was active in the National Council of Women and worked hard against the many double standards pertaining to sexuality in law, but whether she chose to become a lawyer solely to champion the feminist cause is doubtful. It is far more likely she pursued her career because her brilliant mind welcomed the challenge and her determined spirit was willing to persist in the face of overwhelming resistance. Certainly she considered public duty a necessary and honourable responsibility – Clara was the first, and for ten years the only woman trustee on the Toronto Board of Education – but even this role she performed quietly.

In 1913, the Star Weekly interviewed her for a lengthy feature about Canada’s “pioneer woman lawyer.” The article noted that Clara had no hard feelings about her battles with the Law Society and went on to observe that despite her success in the legal profession, Clara Brett Martin had not become “masculinized.” Moreover, the article pointed out, “she is proof that a handsome woman can participate in public affairs without sacrificing the graces of a kindly nature.”

Though the accolades still carried the whiff of old prejudices, it was clear that the tone had changed. Clara must have been pleased.

More Info

Literacy in Mono Township

In 1842, Mono Township had ten one-room schools, more than double the number in similar rural townships. This was likely because Mono took in significant numbers from what is often called the “Sligo migration wave”: educated Ulster Irish who came to Canada after the defeat of Napoleon (1815), but well before the potato famine (from c.1845). Abraham Martin was one of these arrivals, taking up land in the 6th Concession in 1832. He married Elizabeth Brett, daughter of James Brett who owned the neighbouring property. The Bretts had English connections and were quite well-to-do. Commentators describe the Martin/Brett families as “well-bred.”

All twelve Martin children were tutored at home – interesting given that Abraham was once Mono’s Superintendent of Schools – and all received some university education. After forty years in Mono the family moved to Toronto where Clara was born.

An Unfortunate Footnote to a Remarkable Achievement

In the 1980s, as the number of women law graduates came close to equalling the number of men, Clara Brett Martin was “rediscovered” by second-wave feminist scholars. A couple of laudatory articles shot her into the limelight. Chief among the many tributes that followed was the decision by then-Attorney General Ian Scott to name his ministry’s impressive new headquarters the Clara Brett Martin Building.

The glory was short-lived, however. Within a year, an article appeared in The Globe and Mail documenting a 1915 letter turned up by a researcher. In it Clara had written about the forging of property registrations. She repeatedly laid the blame for the unscrupulous activities on the “Jews.”

The charges of anti-Semitism were swift and damning. In particular, an article by prominent lawyer Clayton Ruby declared he was “affronted” and “humiliated” that this “vicious anti-Semite” had been honoured with her name on the Attorney-General’s building. Although Clara also had defenders who argued her attitudes were typical of her times and who noted that some buildings almost certainly bore the name of racist men, she was summarily dropped by those who had glorified her as an icon of women’s achievements and, in 1994, her name was quietly removed from the ministry building.

Comments

1 Comment