No Easy Way to the Promised Land

Getting to Upper Canada took determination – and good luck.

The first pioneers to seek free land in these hills knew that crossing the Atlantic would be difficult. What they didn’t know was that securing a decent piece of property, and then finding it, could be another big challenge.

The misery on sailing ships bound for Canada during the early 19th century is captured in diaries. James Rintoul, whose final destination in 1850 was Amaranth Township, offers an example. “22nd Saturday. Wet and stormy, a child died in steerage. 7th the Sabbath. Corpse of a lady and child put overboard this morning. 9th Tuesday. Wet and cold. Quarrelling in the galley over a fire. Child died in steerage. Another born.”

In 1836, Benjamin Freure, en route with his family to what would become Wellington County, could afford a cabin but their journey was no more pleasant. “Thursday, 19 May. Alas! Sick, sick, sick, very sick today. Friday 20th. Still sick, all of us. Tuesday 7th. Rainy, unpleasant. Buried child in the deep, Died of small pox. Saturday 28th. Sea still rough and weather colder. Cannot get well. Feel I will never be warm again.”

So, whether they were in steerage or on deck, after six weeks or more cramped together on a tossing, disease-ridden ship, passengers must have been relieved to see the heights of Quebec, even if they were disembarking to face more obstacles.

Get to Upper Canada

The key was getting to Kingston on Lake Ontario where, for a fee, ships could provide transport deeper into the country. To do this required an arduous trip up the St. Lawrence against the current, through rapids and around portages. And that was only after a period of quarantine on Grosse Île. Because James Rintoul and the Freures had the good fortune to land when cholera and typhus were temporarily under control, it took them just weeks rather than months to get to Upper Canada. Not so for Donald and Christian Cameron.

Although the Camerons’ arrival in 1818 predated the establishment of quarantine on Grosse Île, it took them 17 months to reach their land near present-day Caledon East. Donald got “lake fever” (malaria), so they had to winter at Montreal. Their journey to Kingston the next spring was disrupted by bad weather and missed connections. And then finally on the Great Lakes their ship sank! Getting to Upper Canada took determination – and good luck.

Then to the land office

The newcomers came to these hills to secure a piece of the seemingly unlimited supply of free colonial land. By the early 1820s, all but a few of the townships had been surveyed with the land divided into thousands of lots – 100 acres was a typical size – along more or less straight lines called concessions. At a government land office, newcomers were readily granted a lot, but to own it, that is, to get a Crown Patent, they had to clear five acres, erect a dwelling 16 x 20 feet and clear roadway along the concession, all within two years.

For the settler, the transaction was very much an act of faith. Lots were awarded by lottery, by negotiation, and sometimes by the arbitrary decision of a government agent. Because the land was remote and utterly unknown, few new arrivals had any knowledge of what they had actually been granted. (In their diaries, both Rintoul and Freure acknowledge their good fortune, but for others there was disappointment. An area of land now contained in Mono Cliffs Provincial Park is an example of the harsh terrain settlers abandoned within a generation or two.)

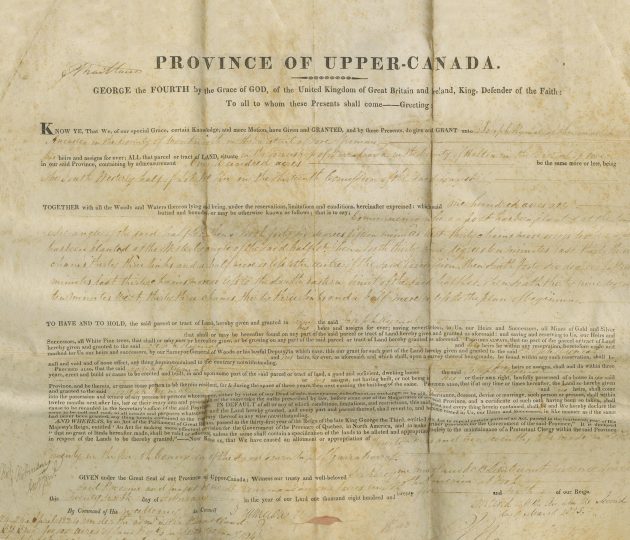

This deed was granted in 1925 to yeoman (farmer) Joseph Rymal, a United Empire Loyalist, for 100 acres on the 19th Concession of Garafraxa. He performed the settlement duties, but did not remain on the property. Courtesy MUSEUM OF DUFFERIN AR-2428-995.

Nor was every lot “free”

For those who actually had a specific property or area in mind, there were often limitations. Before the first land seekers even got here, hundreds of lots were already gone, granted to United Empire Loyalists and British army veterans. Other lots were in the hands of land companies that used their government connections to grab huge tracts to hold for sale. The infamous Clergy Reserves – one-seventh of every township set aside for clergy – pulled still more land out of the system. (Reserves in Erin Township, for example, swallowed up nearly 10,000 acres.)

Even the surveyors themselves owned swaths of land, for they were usually paid in acreage. In Mulmur Township, for example, 3,572 acres were used to reimburse surveyor Alan Robinet, while Albion surveyor James Chewitt finished the job owning 2,635 acres.

Despite the side deals, there were still hundreds of lots in these hills awaiting eager new settlers, and in 1819 one of these was granted to William Downey from Yorkshire, England. At the land office in York he was given a Ticket of Location for Lot 18 on the 8th Concession of Albion Township. The ticket confirmed a provisional grant of his lot. All he had to do was meet the building and clearing obligations, and the property would be his. First, however, he had to find it.

Into the darkness of the forest

Downey is thought to be the first European landowner to sleep overnight in Albion Township. But that didn’t happen on Lot 18, Concession 8. After a storm-tossed Atlantic crossing and a months-long journey to the shores of Lake Ontario, followed by weeks in the trackless wilds of the new township, he simply could not find his property. Downey may not have known it, but at the time, three other Yorkshiremen, William Roadhouse and his two adult sons, were also searching in Albion with Tickets of Location in hand, but they couldn’t find their properties either. It was a common experience for first-in settlers.

To designate concessions and lot boundaries, surveyors chopped blazes on not-always-precisely-located trees. What with random clearings, treeless swamps, thick underbrush and the complete absence of signage, blazes were hard to interpret – or even see. And the Downey and Roadhouse quests may have been extra challenging – according to a history of Peel by Mary Fix, once a county warden, Albion’s survey had been carried out “largely with a chain, a tripod and a jug of whiskey.”

The Roadhouses finally found their property on the second try, but had to hire a surveyor to help. William Downey also found his lot on the second try, but not for another year. To deal with other complications, he first had to go back to England!

Was the promised land worth the struggle?

In The Backwoods of Canada (1836), Catherine Parr Traill wrote, “Canada is the land of hope; here everything is new; everything going forward…” We don’t know if any of our local pioneers ever read her words, but if the history they left us is any indication, they would have agreed with her. The Roadhouses, for one, not only settled but soon expanded their holdings. James Rintoul wrote regularly to his brother in Scotland, urging him to emigrate too (he did). Benjamin Freure’s diary frequently mentions the “benefits” of this new life. Even the memoirs of Donald Cameron, whose trials were many and hard, noted there was “always plenty to eat and drink and to spare.”

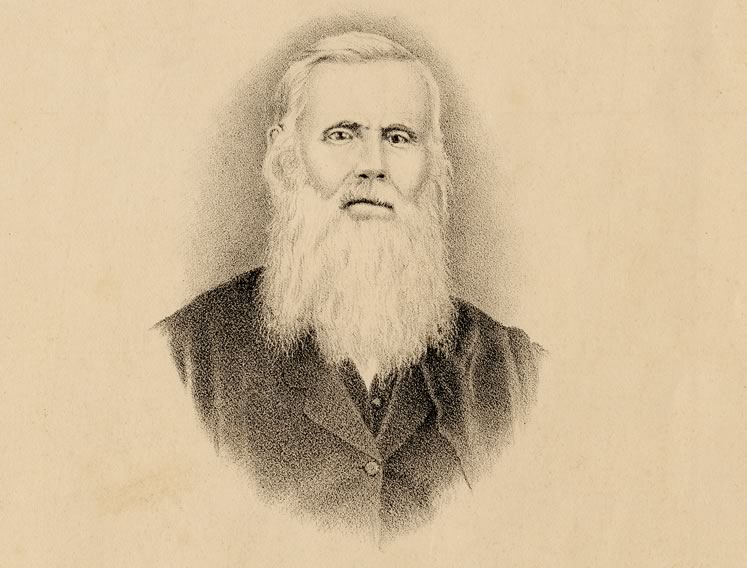

William Roadhouse Sr. (1774-1857) settled on 200 acres in Albion Township in 1819. On the 55,000 acres that made up the township, there were fewer than 100 other settlers that year. William’s son Joseph was a child when the family arrived. See his account of the experience in an excerpt from his 1892 memoir below. Courtesy Peel Art Gallery, Museum + Archives in Brampton.

Perhaps the most powerful affirmation comes from William Downey. Despite an impossibly difficult journey here in 1819, and a frustrating failure to pin down his property, and despite having to go back to England, he readily made the outbound journey again in 1820. This time his brother Henry came too, as did Henry’s wife Mary Ann and Henry Jr. Clearly they believed the land was worth it.

More Info

A gap in reality

Because so many lots in Upper Canada were granted (to veterans and others) well before the wave of settlement began after 1820, many townships were made to appear more populated than they really were. The Township of Garafraxa (today’s East and West) was opened for settlement in 1822, and by 1825 nearly half the lots were gone, making the township, at least on paper, nearly half settled at a time when its population was effectively zero. The first settlers arrived in 1826.

Settling on the wrong lot

It was not unusual for first-in pioneers to misread blazes and settle on the wrong lot. Others “squatted” and went on to fulfill the ownership requirements hoping to deal with legal aspects later. In 1868 in Amaranth Township, Thomas Davis squatted on Lot 21, Concession 8. It was undeveloped land that, unknown to him at first, had been granted to one George Palmer in 1854. Davis and his growing family developed the property, but once the true ownership was discovered it took eight years of petitioning before the Commissioner of Crown Lands allowed him to buy the lot from Palmer (in installments over four years at $1.47 per acre).

Joseph Roadhouse remembers

Joseph was a child when the William Roadhouse family arrived in Albion Township in 1819. A memoir he wrote in 1892 includes this memory of travels through the bush in the very early days.

“… to go through the wild woods with horses and wagons was a strange undertaking for men that had (not) been brought up in a country like this … Father and Mother and five children started on ahead of the wagons and proceeded on our way without any road save a mark on the trees and sometimes that hard to see. Father at times carrying my youngest sister on his back up some of the hills. The wagons then preceded on their way awhile and then came to a swamp and Mr. Hartman put his horses in. The horses went to near out of sight in the water and the mud. With great difficulty they got them out. That was the end of their journey. Then Mr. Hartman and my brother Wm. came to look for us and found us between sunset and dark but we was lost having missed the mark on the trees. Had they not come we likely would have had to lade in the woods supper less all night.”

The picture which you have is of William Roadhouse Jr. He dedicated part of his land to a church/school with cemetery. There is a photo of William Sr at Peel Archives and circulating throughout the Roadhouse descendants.

Bruce D. Roadhouse from Oshawa, Ontario on Apr 27, 2020 at 2:31 am |