Life Is in the Details

Bolton author Glenn Carley reveals glory in the ordinary.

The day of the week is irrelevant – if it is past 5:30 in the morning, Glenn Carley is writing. Short stories, librettos, novellas, memoirs, and children’s fiction all take shape before a typical workday begins, brought into being in the busy writing nook of Carley’s spacious front living room in Bolton. Carley, a retired social worker and prolific author, types carefully but steadily, filling one virtual page after another on the screen of his sturdy desktop computer. He rests occasionally, settling his eyes on various curiosities assembled like stage props around his keyboard and on the upper shelves of his polished wooden writing desk: framed pictures of his wife, Mary, adult children, Nick and Adriana, and one-year-old granddaughter; a stack of jazz and opera CDs; and two sets of figures of Don Quixote with his steed, Rocinante, and squire, Sancho Panza.

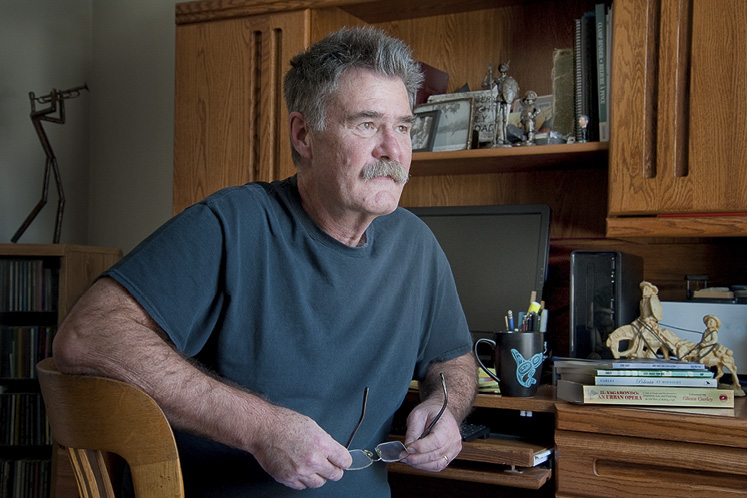

When I joined Carley to hear about his life and work at 9:15 on a Tuesday morning last summer, the author had finished writing for the day. He met me at the door, dressed casually in shorts, sandals and a faded salt-and-pepper T-shirt advertising a local construction company. His hair, caught in intermediate stages of greying, stuck up in an orderly, rectangular mass above his evenly lined forehead; a dense mustache squatted atop his upper lip.

As I followed him up a few steps into a homey kitchen, the author gave no indication of having been out of bed – much less working vigorously – for hours. “Coffee?” he asked brightly, clasping large, kindly hands.

Author and retired social worker Glenn Carley at his writing desk in Bolton: “Finishing is everything. I don’t want to be haunted by half stories or quarter stories.”

We settled at the kitchen table with our mugs, where Carley listened and spoke attentively. From the outset, his thoughts about writing, childhood and art poured forth in earnest, lyrical effusions. Later, when he performed the opening address from his auto-fictional libretto, Il Vagabondo: An Urban Opera, about marrying into an Italian family, that lyric quality became literally musical.

“Come with me,” he sang,

to Garibaldi’s Court and I will tell you

tales of gusto and enchantment.

We will sing, dance, laugh, cry, and eat polenta

at midnight, al fresco…

We will work hard, and then we will rest.

Our conversation centred on Carley’s own hard work. The author took a sabbatical in 2007 to write and publish his first novel, Polenta at Midnight. Between his retirement in 2016 and the morning we met, Carley signed contracts to publish an astonishing 11 books (two of which, Il Vagabondo and Good Enough From Here, the author’s memoir of the two summers he spent in his early 20s at Canadian Forces Station Alert on Ellesmere Island, are already in print). He also published ten short stories in Accenti Magazine.

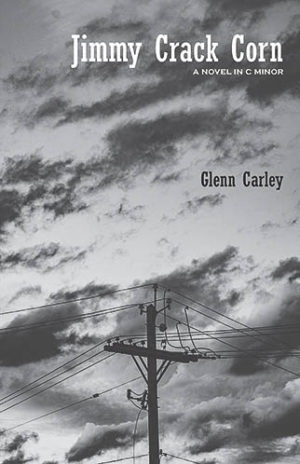

Many of these works preview themes – grief, care, the passage of time – taken up in his latest book, published in October 2022. Most of the three-part, auto-fictional Jimmy Crack Corn, A Novel in C Minor unfolds through memories, recalling the narrator Jimmy’s childhood in the fictional town of Oncewuz during, in a phrase that echoes through the book, “the days before apps, when boys walk the earth.” Dedicated to Mary and “all those souls who protect innocence,” the novel also traces Jimmy’s subsequent career as a social worker. It portrays a man navigating the loss of his own innocence even as he dedicates his life to preserving the fragile capacity for joy and play in others. As such, Jimmy begets admiration not only for Carley’s considerable skills as a writer, but the deep, determined drive toward understanding and compassion the author has sustained over his lifetime.

How, exactly, has he done it all?

When I posed that question to him, Carley explained with a smile that a 33-year social work career and full family life had taught him to make the most of whatever time he could carve out for “the privilege of creating.” His appreciation of that time manifests in the discipline he has applied to his writing since retirement, rising at four or five o’clock and working solidly for the next two-and-a-half or three hours, producing anywhere from three to six pages in a day. “If a writer does that every day, within a month he’s got the bulk of book,” said Carley. He added that “finishing is everything. I don’t want to be haunted by half stories or quarter stories.”

Carley developed his “awe for the majesty of storytelling” as a kid growing up in Trenton, Ontario in the 1960s and early ’70s. Encouraged by his aunt – who sent Christmas gift boxes packed with Hershey’s chocolate and picture books – and his parents, the author “inhaled” children’s stories and comics. When they were older, he and his brother, Dean, raced to the local library, where each would check out six volumes of the Hardy Boys (the maximum number allowed at a time) to speed-read and swap.

In retrospect, said the author, some part of him always wanted to write. But life compelled him toward a career in social work when, undertaking a two-year liberal arts degree at Bryn Athyn College near Philadelphia, Carley worked part-time for a professor promoting “reading recovery” (short-term, one-on-one literacy tutoring for struggling kids) at local elementary schools. After finishing the day’s program with one 10-year-old boy, the two would build Play-Doh figurines, draw, and chase each other around the school. The boy’s reading improved dramatically. Decades later, the experience provided the basis for the relationship between Jimmy’s narrator and the various boys he is trying to help, whom he collectively and affectionately refers to as “Stinky.” At the time, Carley’s boss informed the then-undergrad that he had a natural propensity not only for working with children, but for “therapeutic play” – a method of encouraging self-expression and engagement with repressed experiences through play-based activity.

“That was the first genuine feedback I’d ever gotten from another adult,” remembered the author. “It was the start of a whole social work career.”

The ensuing decades saw Carley embark on a rich set of adventures, many of which are fictionally replicated in Jimmy. He followed a girlfriend from Bryn Athyn to Ames, Iowa, where he volunteered with young offenders and seniors with dementia and pored over theories of therapeutic play in the Iowa State University’s extensive libraries. Carley enrolled in the King’s School of Social Work at Ontario’s Western University two years later and, following graduation, served for 10 months as a youth worker or “playleader” in high-density, low-income neighbourhoods in London, England. He subsequently spent two years as an intake protection worker with the Catholic Children’s Aid Society of Toronto, investigating the social, physical and sexual abuse of minors.

In 1985, while he was studying for his master’s in social work at the University of Toronto, Carley met his future wife, Mary, whose Italian background has supplied another vital mine of material for the writer’s work. The two married in 1986. They moved to Bolton to start a family and Carley settled into a job in the social work department of the Dufferin-Peel Catholic District School Board, where he served as chief from 1995 to 2016.

For Carley, the transition from social work to writing felt organic. His last major undertaking as a social worker was a storytelling endeavour called the Wisdom Project, through which older students recorded their experiences for future, potentially struggling students. And many of the skills and qualities which compelled Carley’s career – determination, a willingness to experiment, an ability to reconcile the particular and universal – translated into his current craft as a storyteller.

As in his career and personal life, in writing Carley is unafraid to experiment or seek out the unfamiliar, particularly where genre and style are concerned. He emphasizes the importance of a “willingness to just go to sea and write and see what happens,” adding that “form is everything.” The author has worked in and stretched the modalities of a number of forms of short and long writing. Such a devotion to craft compelled him to revisit the narrative underlying Polenta at Midnight, for instance, and transform it into his libretto, Il Vagabondo, replete with a “table of performances,” stage directions and intermissions.

Recently, a similar impulse moved him to combine his old recordings of “long stories” he had told Nick and Adriana on car trips or at bedtime with their childhood illustrations to create playful children’s adventure narratives including The Long Story of Mount Pester and The Long Story of Mount Pootzah, slated to come out this year. In Jimmy, his writing shifts fluidly from extended, almost disembodied dialogue to descriptive first-person narrative, weaving in lyric reflection and more immediate storytelling to place the past and present in near-constant communication.

Just as he did during therapeutic play sessions, Carley draws on other mediums to propel and guide his self-expression. A lifelong lover of music (“I grew up in a house with an eternally-playing German Telefunken stereo”), Carley selects a “jazz muse” for each of his writing projects, immersing himself in a musician’s work and attempting to embody their creative spirit. Polenta, for instance, was influenced by John Coltrane; Good Enough by Miles Davis. And Jimmy Crack Corn, of course, draws on the traditional American folk song.

Carley also pulls from the visual arts. His writing nook is cluttered with small miniatures of suggestive figures: along with the Don Quixote characters, there is a whale which reminds him of Moby Dick and a group of horses at play. And in the beginning stages of a project, the writer takes a “meta-view” of narratives by literally drawing out their settings and constitutive components in pencil frescoes on large sheets of blank paper.

The essence of Carley’s work lies in its concentrated attention to the tiny, seemingly mundane particulars of day-to-day life. He refers to these as the “mosto in the mundane,” explaining that mosto in Italian winemaking is the sludge created after one or two pressings. Just as “the astute garage winemaker presses that sludge separately so that it ferments to become a beautiful wine vinegar,” so too does Carley “press” moments to see what they will produce.

This appreciation for the small moment is another vestige of Carley’s social work career, in which curiosity and scrupulous attention helped him connect with children (or, on more serious occasions, proved fundamental to uncovering neglect or abuse). Said Carley, “When you become a social worker and have to investigate some powerful things, you don’t want to get it wrong. Over time you start to notice more and more.” During his social work career and now as a writer, he said, “What should be just ordinary is really interesting to me. I find beauty in a lot of those small things.”

Although Jimmy Crack Corn is magic realist in form, it is grounded in Carley’s ability to conjure small, ordinary things in hyper crisp, full-bodied and often unexpected detail. Describing a tree from which Jimmy and his friends used to jump into the local river, the author writes:

“The tree does what all riverside willows must do. It defies gravity, bursts into the sky and sends cascades of leaves in spray after spray over the water. There is an unruly limb, sturdy as a telephone pole, that reaches twenty feet over the water. The laws of gravity threaten to snap it. In the days before apps, when boys walk the earth, some unknown genius shimmies out to the end and loops a thick nautical rope around the limb. The bark at this point is worn smooth like the rind of a wedding ring.”

Farther into the novel, he sketches a house Jimmy is called to on a Friday afternoon social work shift:

“A radio fades when I tap on the door. The door opens and stops at the chain. A woman asks me what I want, leaves and then I see a man’s face through the crack. I tell him somebody from the community worries about their baby. I ask the baby’s name and tell them my sister’s baby is Tina too. I don’t have a sister and I have no idea how I come up with the line, but it works. […] The chain rattles, the door opens and I walk in. The place is relatively clean. The usual small kitchenette, a living room and TV, hallway to one bedroom, bathroom off the side. I smell the cloying stink of steamed broccoli. There is a twelve-pack under the table and four are empty. It is just information and I compare that information with the fact that there is a twenty-four in the cupboard back at my apartment. They seem nice enough so we sit at the table and get to know one another.”

The same tenacious spirit which drove Carley’s initial self-education and pursuit of a career in social work – indeed, the same persistent passion which summons him from bed each morning – has served him well in the volatile world of writing and publishing. The writer speaks candidly about the challenges he has faced in bringing his work to audiences. In the days following the creation of apps, publishers’ and audiences’ attention can be difficult to capture.

Still, Carley remains undaunted. Just as he jokes self-effacingly about his humble adventures on the “high literary seas” and “Quixotean writer’s journey,” so too does he speak of future projects with undiluted creative vigour. As he professes his intention to keep writing, I am reminded of a quote from Don Quixote itself: “When life itself seems lunatic, who knows where madness lies? Perhaps to be too practical is madness. To surrender dreams – this may be madness.”

More Info

In the days before apps

In Jimmy Crack Corn: A Novel in C Minor, author Glenn Carley explores themes of grief, innocence and pragmatic compassion as they play out over the lifetime of Jimmy the Bleeder.

In Jimmy Crack Corn: A Novel in C Minor, author Glenn Carley explores themes of grief, innocence and pragmatic compassion as they play out over the lifetime of Jimmy the Bleeder.

The book’s first part, or “Chord I (my master’s gone away),” is told primarily through Jimmy’s recollections of his childhood in the fictional town of Oncewuz. In “Chord II (and I don’t care)” the narrative shifts from Jimmy’s “glacial acquisition of competence and freedom” to the start of his career as a social worker, or – to use the novel’s wry term – a Do-Gooder.

Jimmy’s innocence withers amid his investigations of abuse and neglect which begin to bleed into one another and “repeat to infinity.” In “Chord III (the blue-tail fly)” the narrator finds some spiritual relief, if not quite redemption, through fatherhood and the final phase of his work as a Do-Gooder at a struggling high school.

In the following excerpt, a 21-year-old Jimmy is on a pilgrimage back to his hometown. En route his best friend from childhood, Fizzy Jack, materializes next to him in the car, along with three other members of their old crowd in the back seat. Soon enough Jimmy’s “memories replace the linear notion of time and how it ticks” – and the travellers are thrust back to their free-roaming boyhood on the main strip of Oncewuz in the late ’60s.

The centre of the cosmos in Oncewuz is actually defined by three corner stores. Three swirling nebulae, each one distinct but together they form a whole in the cosmic expanse. All reference points, on bike, on foot, later by car are taken from a strip of golden territory about eight hundred metres long, give or take.

Below is an excerpt from Jimmy Crack Corn: A Novel in C Minor.

…………………………………………………………………………………………….

Clarence goes into Phil’s Market to buy another popsicle. Like a raccoon, he fishes out two large pop bottles from the garbage drum, to make the deal. The clang of the bicycle rack splits his popsicle in two. The sound startles me.

“Want half?” he grins.

…

Phil’s atmosphere is nice. It is clean and run by a ma and pa, whose three daughters all have Little Orphan Annie cartoon-hair, tight and always in place. I predict each of them will be a doctor or a surgeon somewhere, well beyond Oncewuz. They are that smart. Mrs. Phil is well-liked by the entire block and runs the checkout. She is tall and blocks the view of the candy counter behind her. It cascades up, almost to the ceiling. She makes a better door than a window. All you do is hand her a hastily scrawled note and some money: “Dear Mrs. Phil. Please give Bleeder two packs of Du Maurier Kings and a sack of honeymoons.” We feel the acceptance, the understanding and the warmth in that store. Everything is nice and orderly and they do not look at you twice if you come in five times a day with empty pop bottles. If there is a river watering the expanse of Eden, this is the variety store guarded by the fiery swords of cherubim. Now serving Little Pest number 23 and all that.

The Handy Dandy is different altogether. Of the three, the Dandy is the only joint that sells firecrackers on Firecracker Day. It is run by whoever is on duty. It is always somebody we do not recognize. Depending on who it is, we do not need a note to buy smokes, either. The firecrackers are stacked in plain view on the counter, in their red cellophane. We can touch them; crinkle the wrappers and lust after them. The candy is behind glass and the glass is smeared with the whorls of a thousand eager fingerprints. Yum. The pop is in a giant cooler in the middle of the store. On summer days, in our search for currency, we learn to pull into the Dandy and mill about.

“Hey, Pinky, I think I’ll have a pop, want one?” someone might say.

This takes the pressure off to approach the cooler. I lift the hatch and run my hand along the tin-coated bottom. With cold water up to my elbows, I sweep for dimes and quarters. When anyone finds a dime: finders keepers, losers weepers. Still, there is something about the Handy Dandy that practically urges me to steal. It is part of the trapline in Oncewuz.

“Hey, Arse-face. How much did you pay for that?”

“Nothing. It’s on sale. Five-finger discount, Bub!” is the local joke.

There is as much going on outside as inside the Dandy. It is seated at a crossroads, unlike Phil’s which is on the way out of town. In the excitement of leaving the block, it is a comfort to rush into Phil’s, say hi-and-bye and head off into oblivion. At the crossroads, however, there is ample entertainment. We just come to watch sometimes. There are no signs to tell you not to loiter. All kinds of characters flow in from the north and the south, the east and the west. In the days before apps, when boys walk the earth, hanging around is a skill.

Related Stories

The Year in Books: 2022

Nov 20, 2022 | | ArtsThere’s been an amazing proliferation of new books this year, and local books always make great Christmas gifts! Here’s our annual round-up of what to read this winter.

The Year in Books: 2021

Nov 29, 2021 | | ArtsFrom mysteries to memoirs, our annual review of new books by local authors and illustrators has you covered for gifts for others – and yourself.