It’s Baby Season at the Wildlife Centre

The spring rush of young, orphaned or injured animals marks the start of another busy year at Procyon Wildlife and Rehabilitation Centre.

Come spring, the poet wrote, a young man’s fancy turns to love. As does the fancy of all the wild creatures of forest and field. And for the staff and volunteers at Procyon Wildlife Rehabilitation and Education Centre in Beeton, this means one thing: all hands on deck for the busy “baby season.” With warming winters, this time of year is coming earlier and earlier.

The arrival of all those hungry young mouths was still ahead when I visited Procyon in January. However, I did meet sleepy bats hibernating in a fridge, a feisty raven named Edgar, and a mink on the lam from a fur farm.

“Procyon” (pronounced PRO-see-on) is the genus name for raccoon. But this rehabilitation facility, just east of Headwaters, has been caring for all manner of injured and orphaned animals – now an astonishing 1,500-plus annually – since it was established in 2009. Mammals make up the bulk of admissions. In 2023, 329 squirrels topped the list, consisting of two species: red and grey. But cottontail rabbits and raccoons weren’t far behind, with 319 and 307 admissions respectively.

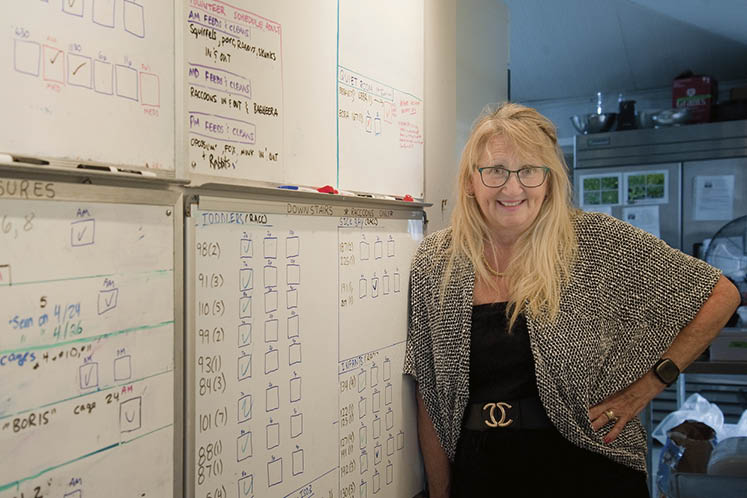

The bipedal primates who keep all these animals fed, watered and healthy include Debra Spilar, who has been a driving force behind Procyon since the beginning; Crystal Faye, primary animal care/triage co-ordinator and director, and the only full-time staff member; and Kylee Hinde, who works part-time as the assistant animal care/triage co-ordinator.

Backing up these core staff members are scores of essential volunteers, critical to the functioning of Procyon, especially during baby season. Last year’s unusually warm January and February saw animals emerge from hibernation, mate and produce offspring much sooner than usual. At one point early last spring, Procyon had more than a hundred baby raccoons on a round-the-clock feeding schedule. All that bottle feeding requires lots of human hands. When it looked like this winter would be another warm one, Debra brought forward the onset of the official baby season and its requisite volunteer planning by a month, to March 1 from April 1.

I was struck by the positive energy exuded by everyone at Procyon. Though the work is demanding and can be emotionally draining, it was clear their passion for helping their fellow animals provides ample reward.

Debra formerly ran a marketing business, experience that translates well into running Procyon. Her pet-filled house also prepared her for an essential Procyon job – cleaning up animal poop. Her rather complicated title reflects the many hats she wears at Procyon: custodian, inventory controller, education programmer and administrator, and director. Handling the education programs is one of her favourite roles. Procyon teaches school groups, among others, about all things animal.

Crystal earned a diploma as a veterinary assistant, then became a stay-at-home mom, and when time allowed she began volunteering at Procyon and was eventually hired to co-ordinate primary care and triage. She was the one who showed me the bats in the fridge. “We have five big browns in there right now,” she said. “Every two weeks we wake them up, feed them mealworms and put them back.” In spring, when flying insects are available outdoors, the bats will be released.

Kylee, who assists Crystal, has an undergrad degree in music as well as a degree in social work and, for a time, worked with adults with disabilities. Like Debra and Crystal, she’s crazy about animals. Asked about the most difficult animals to work with, I expected her to mention coyotes or raccoons. She didn’t hesitate. “Chipmunks!” Apparently these tiny, cherubic-looking rodents can be absolute beasts. Who knew?

Along with raccoons, squirrels and rabbits, Procyon cares for foxes, coyotes, voles, deer, bats, groundhogs, opossums, weasels, mice and skunks. A fisher and a salamander have been among their more unusual patients. Birds are sometimes admitted but most are sent to Shades of Hope Wildlife Refuge in Pefferlaw, which specializes in their treatment. In turn, Shades of Hope reciprocates by sending mammals to Procyon, including 60 skunks last year. In all, Procyon rehabbed 90 of those aromatic mammals in 2023.

Among last spring’s more beguiling admissions were two tiny porcupines, affectionately called “porcupets” by the staff. The first – the size of an apple – was found by a landowner in Creemore. It was newly born, with its umbilical cord still attached. Kylee laughs as she remembers talking to the rescuer on the phone. “I think I’ve found a hedgehog!” the caller said.

As if preordained, only two days after this diminutive pin cushion was admitted, a call came in from Thunder Bay offering another baby porcupine. Ever resourceful, Debra arranged for a dog rescue service to relay the porcupine to Procyon. The centre doesn’t take in many porcupines, so to have two arrive within days of each other was a stroke of luck. Whenever possible, Procyon tries to house animals with members of their own species so they can socialize with their own kind and learn from each other, improving their chances of survival when released.

This strategy worked for the porcupets, which didn’t imprint on the centre’s staff or volunteers. Though they would come readily for food – apples were a favourite – they did not hesitate to raise their quills if upset. And when angry with their human handlers, they’d throw little temper tantrums, running in circles, spinning and screaming.

Animals arrive at the centre for a variety of reasons. Some suffer from mange, a debilitating condition that results in fur loss and is caused by an infestation of mites. Many arrive injured after run-ins with cars. Fractures and head injuries are common. Debra advises people who find an injured animal to move it as little as possible and to bring it to the centre quickly. Head injuries in particular need prompt treatment. Many animals with head trauma can recover if they receive timely care.

Leg injuries sometimes require amputations, and in testament to the remarkable resilience of animals such as foxes and raccoons, having three legs does not necessarily preclude a return to the wild. Procyon calls on a variety of local veterinarians to examine animals and perform surgery if necessary. Assistance often comes from the National Wildlife Centre in Caledon East and its qualified wildlife veterinarians, including Dr. Sherri Cox, NWC’s co-founder and medical director.

Other injuries are caused by domestic dogs and by house cats. House cat depredation of wild animals in North America is well-documented and responsible for the deaths of tens of millions of birds, small mammals and reptiles annually. Debra pleads, “If you insist on allowing your cat to roam free outdoors, at least have it wear a bell. Know also that outdoors, it becomes part of the food chain. Coyotes can’t tell the difference between a wild animal and a domestic one.”

Some of the injuries inflicted underscore the dark side of human nature. In Barrie in 2017 a young raccoon was set on fire with lighter fluid. Burned over 40 per cent of its body, it was christened “Phoenix Rose” by Procyon in hopes that it might rise from the ashes and survive. It didn’t, soon succumbing to trauma-induced pneumonia.

Another sad testament to the depravity our species is capable of was a squirrel pinned to a tree by an arrow through its chest. He didn’t make it either. BB guns take a toll, and occasionally animals are found struggling in snares set illegally by poachers.

Procyon, with its abundant compassion, offers a life-affirming contrast to these acts of violence. The scores of Procyon volunteers, and the legions of people in our communities who care, greatly eclipse the bad actors. This is something worth remembering when stories of unspeakable cruelty arise.

Sometimes, however, caring and goodwill can end up unintentionally hurting animals. Kind-hearted human beings react with understandable concern when they stumble upon an injured or baby animal in the wild. With injured animals, the way forward is clear: contact a rehab centre such as Procyon. But with babies, caution is necessary.

Often the mother is nearby, watching anxiously. It’s best to wait a while and check back regularly. White-tailed deer mothers, for example, leave their nearly odourless fawns in place for hours. This is in part because the mothers emit a scent that can attract predators. So, it’s best for them and their fawns to be separated for much of the day.

Speaking of fawns, one of the heartwarming stories I heard at Procyon was about “Willow,” a tiny white-tailed deer that had been hit by a car. Willow needed orthopedic surgery to repair an injured hip. The estimated cost was an eye-watering $6,800. Debra and her staff were unfazed. An animal was in need, and they would make it right, regardless of the cost.

What happened next speaks to the power of kindness. The orthopedic surgeon, delighted by the opportunity to operate on a baby deer, performed the operation at cost: $1,800. Within 24 hours, a social media campaign on behalf of the fawn brought in that amount and more.

Another story to tug the heartstrings features “Talitha,” a tiny fox kit, so young her eyes hadn’t opened, found cold and alone in a snow-covered field. Her parents and siblings had been killed by predators, likely coyotes. Unaccountably, she had been left unscathed.

Named for a little girl who was, according to a biblical account, brought back to life by Jesus, Talitha and her story generated more than 200,000 YouTube views. She thrived under Procyon’s care, exhibiting the curiosity and intelligence her species is known for.

Eventually another young fox came to Procyon and was introduced to Talitha. Early distrust soon yielded to curiosity and lots of rambunctious play. After growing up and demonstrating the ability to hunt, both animals were released into the wild. As the two bounded off into a meadow, the Procyon staff basked in the glow of an ideal rehabilitation effort. “It’s what makes all the late nights and early mornings worthwhile,” said Kallie, a Procyon volunteer in a YouTube video. “This is our definition of a happy ending.”

Another happy ending was rather unexpected. A horse farmer had called to report an emaciated mange-ridden coyote desperately trying to keep warm by lying on mouldering manure. The coyote was easy to approach – resigned, it seemed, to his fate. “We picked him up almost like a baby,” says Debra. “He had no fight left in him at all.”

Procyon worked its magic. The coyote’s fur grew back, his health returned, and he was deemed ready for release. But where to? Surely the farmer didn’t want the coyote back. It turned out she did. “I want him here,” she said. “My horses aren’t afraid of coyotes, but they’re terrified of the mice the coyotes eat!”

Returning rehabilitated animals to their home turf is taken very seriously by Procyon. The Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry mandates that animals be released near where they were found, a policy the centre embraces. Animals, like us, know their home territory – where to find food and where to find shelter. Another imperative governing this policy is the prevention of disease. Bats, for example, may carry the spores of white-nose syndrome, a fungus that has killed millions of these creatures in North America. It would be irresponsible and potentially damaging to release them beyond where they were found.

As you might expect, all the good work Procyon does, and the hundreds of animals it supports annually, requires large sums of money that largely flow from generous donations. Each mammal species, for example, needs its own bespoke formula mix. You can’t feed a herbivore like a porcupine the same formula required by an omnivore like a raccoon. These species-tailored formulas ship from the U.S. at $500 for a 20-pound pail.

Along with financial help, Procyon requires at least 150 volunteers during the spring birthing season. If you are tempted to join the Procyon team, be aware that though bottle feeding cute baby animals is heartwarming, there are plenty of less endearing chores that need doing: laundry, dishwashing, preparing formula, and the herculean task of cleaning all the cages. This is done every time the animals are fed. How often is that? Babies are fed six times a day and adults morning, afternoon and evening.

Clearly though, volunteers think it’s worth it. Lorysa Cornish, an Orangeville resident seeking to shake the Covid blues in 2021, reached out to volunteer at Procyon. “Starting as a volunteer at Procyon was an amazing experience,” Lorysa remembers. Engaging in the meaningful work of caring for animals was just the tonic she needed to cope with the Covid doldrums.

Lorysa fell in love with “Gideon,” a fawn that was stressed and not eating well. On one of her evening shifts, Lorysa was determined to help. She gently encouraged Gideon by, she says, “acting like a mother deer would. I gently stroked his belly and tail area. He responded by bumping his nose into me, something they do with their mothers when wanting to nurse.”

So Lorysa repeatedly offered the bottle, but Gideon seemed confused. And then, at last, success! He latched on, “drained the entire bottle, had a good pee, and then settled down for a snooze.” Lorysa was so relieved that she almost cried. Gideon grew into a healthy adolescent deer and returned to the wild.

Lorysa’s story reinforced the impressions so amply conveyed by Debra, Crystal and Kylee. Procyon not only serves the critical needs of thousands of animals but is also balm for the spirits of their human caretakers.

WHAT TO DO IF YOU FIND AN ANIMAL IN NEED OF HELP

Along with a section on what to do if you find an animal in distress, the Procyon website includes information on how to volunteer, a comprehensive list of other Ontario wildlife rehabbers, and how to tap into Procyon’s education programs. You can also follow them on Facebook. Visit their website at procyonwildlife.com or call 905-729-0033.

Procyon tries not to turn away any animal in need, but if the centre is full, they may refer you to another rehab centre or arrange transport for certain animals to facilities that specialize in their care. Bears, for example, would be sent to Bear With Us Centre for Bears in Sprucedale, Ontario. Visit bearwithus.org for more info or call 705-571-4397.

Procyon will occasionally take in raptors, but Shades of Hope in Pefferlaw specializes in avian recovery. Visit shadesofhope.ca or call 705-437-4654.

Likewise, the Ontario Turtle Conservation Centre in Selwyn, Ontario, specializes in caring for these shelled beasts. Visit ontarioturtle.ca or call 705-741-5000

Volunteers are always welcome, especially right now, during “baby season.” And speaking of babies, check out YouTube for the story of Talitha, the cutest little baby fox.

National Wildlife Centre

The NWC has served the conservation and rehabilitation needs of wildlife since 2014, offering veterinary expertise to Procyon and other wildlife rehabilitation centres across Canada. Co-founder and wildlife veterinarian Dr. Sherri Cox has worked for a decade out of a mobile wildlife hospital. This will soon change. Construction on a state-of-the-art wildlife field hospital is now underway in Caledon and, barring delays, could be open in the fall or early winter. Visit nationalwildlifecentre.ca or call 416-577-4372.

Related Stories

Healing Powers

Mar 20, 2023 | | Environment“How could I not help those animals that don’t have a voice?”

Wildlife Rescue: Cry of the Wild

Mar 26, 2018 | | EnvironmentSherri Cox, a corporate executive turned wildlife vet, takes her surgical skills on the road to aid animals in distress.

Our Ever Heavier Urban Footprint

Feb 27, 2023 | | Notes from the WildAs development continues unabated, our growing population and urban footprint will inevitably diminish biodiversity.

New Kits on the Block

Mar 31, 2021 | | EnvironmentRed foxes are making themselves at home in Inglewood, Grand Valley and Palgrave, hunting in our yards and denning under our sheds and garages.