Growth and Prosperity

Growth and Prosperity: Do they go together like a horse and carriage? Or is the concept just as antiquated?

It was a strange dream: I called up Alan Tonks, the new chairman of the Greater Toronto Services Board, and I said, “Al, how do we get out?” He asked, “Out? Out of what?” I said, “The GTA, Al. How does Caledon get out of the Greater Toronto Area?” A little startled, he asked, “Why on earth would you want out?” And I said, “Because Al, we’ve decided that in Caledon we’ve had enough. We’ve reached the environmental carrying capacity of the land and we don’t want our roads to become linear parking lots. We’ve seen Highway 400 on Sunday night. We’ve tried to drive through Newmarket. We’ve visited Bramalea and know what ticky-tacky looks like. We’ve seen urban sprawl and we’ve decided it isn’t for us. We like Caledon just the way it is.” He just chuckled and hung up.

People who migrate from the city into rural areas and then want to close the door behind them are sometimes criticized for being “drawbridge environmentalists”, because they want to draw the bridge up after them and shut everyone else out. Alan Tonks would hardly be alone in believing that a request from Caledon to escape from the GTA and its pressure-cooker style of growth smacks of protectionism. And thoughtful rural immigrants are not insensitive to the charge.

In a recent issue of New York Times Magazine, Michael Pollan writes that he had always assumed that his small community on the outskirts of New York City would “eventually succumb to the ineluctable, almost geologic forces of sprawl. There didn’t seem much anyone could do about it, at least nothing that didn’t feel selfish or elitist or hypocritical, not to mention perfectly futile.” Nevertheless, in rural communities across North America, from the outskirts of New York to the outskirts of Toronto to the outskirts of Orangeville, there’s a rumble growing in the countryside.

Throughout the twentieth century, urban development has been propelled by the seemingly incontrovertible maxim that Growth equals Prosperity.

The unquestioned corollaries to the equation are that Growth equals Lower Taxes, Improved Services and More Jobs.

The argument goes like this: If a municipality attracts more people and more business, it brings in more tax revenue. The cost of growth is covered by development charges, and jobs are created. The tax rate for businesses is three to four times higher than the residential rate, but businesses use fewer services, so they subsidize residential taxes. Thus, by attracting more business, a municipality can afford to increase its population and bring in even more taxes. Services improve, there are more jobs, our lifestyle improves, and taxes fall. Right? Well, maybe not.

As the sun sets on the century, shadows of doubt have begun to creep across some of these apparent truths. Sharon Marshall, treasurer for the Town of Erin, for one, disputes them. “Services cost more, not less, in larger municipalities,” she says. Andrew Sancton, a professor of political science at the University of Western Ontario, goes a step further. He says, “It happens to be true that municipalities with more people in them spend more on a per capita basis.” Their voices are joined by an emerging literature that has begun to take a much closer look at the real costs of paving paradise.

In a book entitled The Economic Resource Guide, two Harvard economists, Alan Altshuler and Jose Gomez-Ibanez, report that: “The available evidence shows that development does not cover new public costs; that is, it brings in less revenue for local governments than the price of servicing it.”

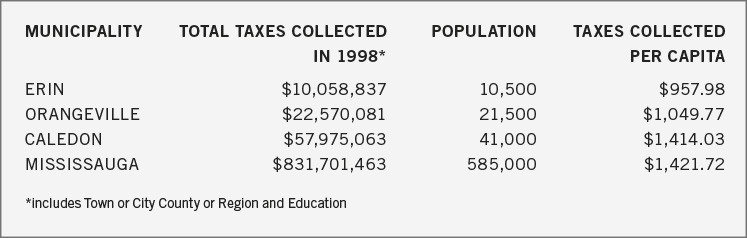

A simple test here in the hills seems to validate the theory. Consider the total taxes collected by a municipality on a per capita basis. (They include lower tier, upper tier and educational taxes and are not the taxes paid per person.) The common assumption is that as a municipality gets larger, economies of scale kick in and fewer taxes have to be collected per resident. Well, as Sharon Marshall predicted, it’s not so. Instead, taxes collected per person are higher in Orangeville than in Erin. They are higher in Caledon than in either Erin or Orangeville, and higher again in densely populated Mississauga (see table page 20).

Caledon treasurer Sam Jones suggests the reason for Caledon’s high tax rate is due in part to the town’s large geographic size, its huge collection of roads, and its high level of services. Certainly Caledon looks after a lot of roads – 730 kilometres compared to Orangeville’s 90 kilometres – and Caledon residents paid for their roads to the tune of $9-million in 1998. Caledon also has a very sophisticated waste management system (see In the Hills, Summer ’99), superior police protection, and some of its communities are linked by sewer lines to Lake Ontario.

But if we consider that Caledon must collect more taxes per capita than, for example, Orangeville or Erin, it seems evident that at least some of these “high level of services” are the cost, not the benefit, of population growth and industrial expansion.

Roads are paved when a gravel surface can’t handle the traffic; high-tech waste management is necessary when the volume of garbage becomes a serious environmental threat; improved police protection is necessary when crime, or the fear of it, escalates (and the countryside is no longer a place where doors are always open); and expensive sewers become necessary when local water supplies become contaminated.

Eben Fodor, a professional community planning consultant in the U.S., has written a book called Better Not Bigger: How to Take Control of Urban Growth and Improve Your Community. In it, he sets out to “explode the myth that growth is good for us.”

Using data from several American studies, Fodor convincingly argues that growth tends to inflate taxes, not lower them. But, at first glance, a 1994 study prepared for Caledon by Coopers & Lybrand appears to undermine his thesis. The “Growth and Economic Management Strategy Study” reported that between 1990 and 1993 the net fiscal impact of residential and commercial/industrial growth in Caledon was $201,000, a 31-per-cent positive return on investment. In other words, after spending $649,000 on new roads and road maintenance, fire suppression, general government costs and development expenses, the town generated $850,000 in new taxes.

However, in spite of this apparent windfall, Caledon residents saw no reduction in their annual tax bills. Instead, according to Sam Jones, the town was able to offset inflationary tax increases and hold tax rates at bay for a longer period of time. But isn’t this just a euphemistic way of saying that the extra money was needed to cover the cost of growth not identified by the Coopers & Lybrand study?

According to Eben Fodor, the kind of hard-cost accounting reflected in such studies fails to take into account the many, often long-term and irrecoverable, environmental and social costs associated with development.

His disturbing list of such environmental and social costs includes: decreased air quality, decreased water quality, increased rate of consumption of resources (water, aggregates), increased noise, lost open space and resource land (farms and forests), lost wildlife habitat, increased regulation (loss of freedom), lost mobility due to traffic congestion, increased cost of housing, higher cost of living, increased crime, repair costs to future generations, and loss of sense of community.

Some of those costs are already mounting up on the local tally sheet. Traffic congestion, for example, has become a familiar problem to residents of Orangeville, Caledon Village and Erin. In Orangeville, $700,000 has been put aside for a southern bypass. The solution may relieve traffic jams along Orangeville’s main drag, but the planned route will take Caledon farmland out of production. Negotiating its expropriation has already resulted in some hard feelings between the two municipalities.

The estimated cost of widening the highway through Caledon Village is $2-million (a provincial expense because Highway 10 is a provincial road), however, the figure doesn’t include the price paid by villagers. A bigger, faster highway through the centre of the village will further disrupt the already divided community core. In Erin, the ongoing debate about the huge number of 18-wheelers that use Main Street has pitted truckers against villagers who are concerned about the safety of their children and crumbling house foundations.

In Bolton, growth is exhausting ground water supplies, so this community will soon be drinking treated water from Lake Ontario. At a cost of $17.2-million, construction of a new pipe connecting Bolton to Lake Ontario will begin next year. The new pipe makes way for a 50-per-cent population increase, to 24,000 from 16,000, making Bolton bigger than Orangeville is now.

In Caledon East, a $22-million sewage treatment system completed in 1996 is permitting that community to grow to as many as 10,000 from its current population of 2,000. In Inglewood, two subdivision applications have pushed up the approved mature state population for this sleepy enclave to 1,450 from under 1,000.

Caledon’s official policy is to minimize the negative impact this growth could have on the countryside by containing it in specific towns and villages. However, it really doesn’t matter how you cut it, more people translates into more cars, increased water demand and more stress on the environment. It becomes apparent that the Growth equals Prosperity equation is like a treadmill – growth requires more services that in turn require more tax revenues that require more growth.

One solution that’s finding favour in both Orangeville and Caledon is to emphasize industrial and commercial expansion over residential growth. Industries pay taxes at up to four times the rate of residents, and commercial businesses pay up to three times the going residential rate. Yet, these businesses don’t use many public services beyond local roads, water, electricity and waste disposal.

In a letter to the Orangeville Citizen, Orangeville Mayor Rob Adams says “…Council [in Orangeville] has refocused the town’s development, moving away from rapid residential growth and aggressively pursuing new industrial development.” That’s not to say Orangeville won’t grow – it’s still estimated the population will increase to over 45,000 from 21,000 in twenty years – but the emphasis has changed. The mayor continues: “…we are now extending services and roads into undeveloped industrial lands in town for the coming year. This will provide serviced industrial land which will allow more industries and businesses to locate in our community.”

Caledon also has an aggressive economic development strategy, including a full-time economic development officer to attract business to the town. A glossy brochure describes the town’s attributes and lets it be known that “Council’s commitment to encourage industrial and office commercial investment has resulted in the designation of an additional 1,200 new acres for industrial development.” (In addition to the 700 acres already available.)

In theory, the cost of this new development should be covered by development charges. Those are the charges developers pay to offset the cost of adding the services and infrastructure required by new industrial/commercial or residential development without increasing the burden on existing taxpayers.

However, according to Orangeville’s treasurer, Bruce Taylor, developers have successfully lobbied the province to remove some significant items from the Development Charges Act of 1997. All Ontario municipalities were required to recalculate their development charges by the end of August to reflect the deletions. The cost of adding new cultural and entertainment services, such as museums, theatres and art galleries, are now excluded. Tourism facilities are also eliminated. Hospitals are out and municipal offices have been scratched from the list. A charge for new waste management facilities, such as Orangeville’s proposed landfill, is no longer allowed. Development charges can be assessed only for water, waste water, storm water drainage and control, roads, electricity, policing and fire protection.

From now on, if a growing municipality wants to maintain the same level of cultural, recreational and health-care services as it has had in the past, it will have to rely more heavily than ever on tax revenues to pay for them. Furthermore, while expanding the business base in a municipality may subsidize residential tax rates and thereby keep them artificially low, it doesn’t reduce the overall cost of operating the municipality. In fact, as the table shows, taxes needed per person in highly industrialized Mississauga are double those collected in rural Erin. The changes made to development charges will weaken only further the argument that growth can reduce taxes and improve services.

So, what’s left of the Growth equals Prosperity equation? Harry Kitchen, an economist at Trent University, says that the promise of jobs is a big carrot held out by new development.

In fact, almost 500 new jobs have been created in Caledon since the beginning of 1998. Caledon’s largest employer, Husky Injection Molding Systems, keeps about 1,500 people busy at its facilities in Bolton. In Orangeville, major employers include the Clarks Co. of Canada (formerly First Brands) which employs about 260 and Johnson Controls which has 500 employees.

Such companies are generally good corporate citizens. They pay taxes at a rate up to four times higher than local residents and they do employ people. However, they don’t necessarily employ local people. Fewer than 20 per cent of the jobs at Husky Injection Molding, for example, are filled by people who actually live in Caledon.

In Orangeville, there appears to be an employment rate of better than 100 per cent. For the town’s resident labour force of 9,360, there are 9,455 jobs. The numbers appear to argue persuasively against job creation as an incentive for promoting development. However, Alan Young, the town’s director of planning, acknowledges that only 55 per cent of the available jobs are filled by people who actually live in Orangeville.

In some ways, having a non-resident workforce seems like a good idea. Local municipalities receive the taxes paid by these companies but don’t have to provide all the services their employees require. On the other hand, non-resident employees enjoy the benefits of local roads, recreation and other services without having to pay for them. By extension, some planners have suggested that big box stores should pay a head tax for each out-of-town shopper, since these consumers don’t pay local taxes either.

Here in the hills, our quality of life is largely defined by our rural surroundings. But with both Orangeville and Caledon slated to more than double in population over the next twenty years, efforts to maintain that quality of life appear to be on a collision course with municipal and provincial planning policies. If the trend continues apace, it won’t be long before our municipalities cross the line between rural and urban. Farmland will become suburbs, villages will become towns, and towns will become cities.

Caledon’s future is complicated further by its inclusion in the Greater Toronto Area. The GTA seems to be all about more…more people, more factories, more cars, more things. Unfortunately, the corollary of growth is often less…less farmland, less greenspace, less clean air and water, less wildlife habitat, and less community spirit.

Newcomers who want to limit further development in the hills may indeed be “drawbridge environmentalists.” But, for the most part, they were drawn to these hills in search of the same lush and tranquil environment that makes longtime residents stay put. The evidence is mounting: bigger is not better. Nonetheless, it will take the combined effort of us all – newcomer and longtimer alike – to keep Michael Pollan’s “ineluctable, almost geologic forces of sprawl” at bay.

Nicola Ross is a biologist and environmental consultant who lives in Belfountain. She recently helped found the Caledon Countryside Alliance.