High Stakes in the High County

The Highland Companies, a U.S.-based investment syndicate, has assembled 9,500 acres, most of it in Melancthon, but many people in the community, led by NDACT, worry about the future of their farmland and water resources.

Cropland, aggregate, rail, water, wind. It’s hard to imagine a list more defining of the preoccupations of our times. But what happens when all those elements converge in one community, courtesy of one developer? Is it a bright vision of a sustainable future, or crass “rural blockbusting” set to devastate farmland and decimate a community? In Melancthon, the battle lines are drawn.

If you drive 15 minutes up Highway 124 north of Shelburne, beyond Horning’s Mills into the far corner of Dufferin County, there’s a place where you crest a rise and the horizon drops away. Fields of amber barley and green potato plants stretch away in geometrically perfect rows. The land gently undulates. Dense clumps of hardwood bush float like islands. And at the edges of it all the land meets the sky and clouds in a way that says there is nothing higher for miles. You’ve arrived at the top of the world, and it’s beautiful.

Wind, cropland and stone – three valuable commodities for a shrinking planet – exist here in abundance. The soil, class 1, is the best in the country. The wind bows the trees, drifts the snow and spins the hundred-odd turbines in the western sky. The limestone bedrock of the Niagara Escarpment extends as much as 20 storeys below the topsoil and holds the water that feeds the crops.

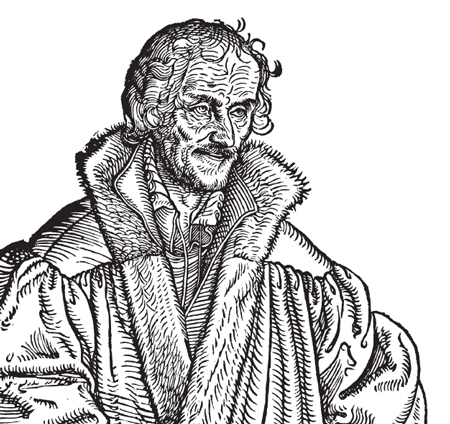

Potato and cattle farmer Jim Black in his Cessna 150: “What are we going to say to our kids, our grandkids, when they ask, ‘What happened around here? Why is this hole in the ground?” Photo by Bryan Davies

John Lowndes, a businessman whose sights fell on the area several years ago, probably saw this and more: that the market of the GTA and the port of Owen Sound are only 100 kilometres away in opposite directions. There’s an old rail line nearby, connecting the two.

Melancthon Township has large swaths of land designated for aggregate and is business friendly – just look how fast those wind turbines went up. Because the land was cleared for farming long ago, and has remained in production ever since, there are none of the protected areas that make development so challenging in the rest of southern Ontario.

The Greenbelt is well to the south, the Niagara Escarpment, with its weekend homes and environmental politics, is safely apart in the neighbouring township of Mulmur. And the farms, many of them consolidated by modern economies of scale into large acreages, give it the appearance of a giant game board just waiting for someone to roll the dice. Surveying this land, John Lowndes must have been amazed that nobody had come in and bought it all up.

So he proceeded to do just that. This plateau, centred on the hamlets of Honeywood and Reddickville, spans 14,000 acres. Today, Lowndes owns half of it – about 10 per cent of Melancthon Township. By acquiring two large potato farms in the process, Wilson’s and Downey’s, he become Ontario’s largest potato producer, as well as Melancthon’s largest employer, taxpayer and corporate donor. Lowndes is the region’s brand new, first-ever, 10-tonne gorilla, and everyone’s watching to see his next step.

A slick corporate DVD landed on local doorsteps last April. The video introduced Lowndes’ corporation, The Highland Companies, and broadly outlined its vision: Continue farming, develop aggregates, bring back the railway, and build wind farms. It presented a future of sustainable development both benign and exciting, the logical evolution of land use in a township that has always depended on resources for prosperity.

It seemed like a perfect plan, but it bogs down in the details. Many of the area’s farmers have taken issue with how John Lowndes acquired the land, what he plans to do with it, and especially what he’ll leave behind.

When they look into Lowndes’ bright future, they don’t see the potato fields, majestic wind turbines and carbon-efficient trains. They see a massive ugly pit, into which will go their farmland and their water, and out of which will come money – lots and lots of money – that will be shipped far out of their community to foreign cities where it will line the pockets of investors who have never touched this land, never put their hands in its excellent soil.

Those farmers started NDACT last January – the North Dufferin Agricultural and Community Task Force – and produced a map showing a spur line straight from Lowndes’ holdings to the railway. They held public meetings in Honeywood to talk about their suspicions and their fears.

Then the story became a lot more complicated. It was as if John Lowndes was not a gorilla after all, but a bear – and he had just put his nose into a hive of bees. In July, when Highland held an open house to announce that it would be applying for a quarry licence of 2,400 acres, an area two-thirds the size of Orangeville, the bees began to swarm.

John Lowndes grew up outside Orangeville. His father, Robert Lowndes, worked for the Armbro group of companies, a construction conglomerate, now the Aecon Group. In 1983, Lowndes graduated from Queen’s

Ron Speers sold his 300-acre farm to The Highland Companies in 2007. His house has since been torn down and the farm fencerows cleared: “I feel sick when I drive down the road now. My whole childhood’s gone, something the whole family worked hard for.” Photo by Bryan Davies

University as a civil engineer and went on, in his words, to “a number of different careers.” Recently he was a sole proprietor doing “turnarounds in the United States” for his current investment partner in The Highland Companies.

In a brief phone interview, Lowndes identifies that partner as The Baupost Group, a $14 billion, Boston-based hedge fund, headed by investment guru Seth Klarman. In partnership with Baupost, Lowndes founded Highland in 2006 to develop resources in Melancthon Township. Late that year, after extensive research, Lowndes approached a number of landowners, offering them $8,000 an acre, 30 per cent or so above market value. Lowndes hoped, he says modestly, to get 1,500 acres to run a profitable potato operation.

He needn’t have worried. Lowndes purchased his first 25 acres in Melancthon in November 2006. Within six months he owned 4,400 acres; within a year, 6,500. Today, The Highland Companies owns 7,500 acres in Melancthon and additional lands in Mulmur Township and Norfolk County – 9,500 acres in all. “It was a little bit surprising,” Lowndes says by way of explanation. “All of a sudden everybody wanted to sell.”

Not absolutely everybody. Jim Black is one of NDACT’s founding members, and one of the first farmers to be approached by Lowndes. Like NDACT itself, everything about Jim Black is a little rough around the edges – improvisational jazz to Highland’s classical order. The sign advertising his farm, fronting on Highway 124 south of Reddickville, says J.D. Black Pigs & Potatoes, even though the Blacks replaced pigs with cattle years ago.

When Black offers to take me up for a flight to show me the lay of the land, his plane turns out to be a suspectlooking 30-year-old Cessna 150 that he bought in 1981 for less than $5,000. He abruptly aborts our first run down the grass airstrip behind the barn because he forgot to take the cover off the airspeed sensor, shouting, “I knew something was wrong!”

Back on the ground in the Blacks’ living room after the flight, Jim’s wife Marian produces a sheet of paper listing the several dates when Lowndes or his representatives approached them about selling. “He was pretty arrogant and thought all he had to do was walk in and we’d sign everything,” she says.

Those were some tough years for farming. “We owed money all over the country,” says Black, but they didn’t want to sell. Then they heard that Lowndes was talking to their creditors. Their seed grower in Saskatchewan phoned to say that Lowndes wanted to pay their seed bill – a way to get control of them, the Blacks figured.

Lowndes counters that Black and other members of NDACT were just too greedy to accept his offers. “There was a discussion with his seed creditor,” he admits, but says it was the creditor who approached Highland. “We could have done that [struck a deal with the creditor]. We did not do that.”

When Lowndes kept coming back, the Blacks had had enough. They put a price on their land that was high enough to send him away for good. When they found out about the quarry, they joined NDACT’s fight.

“It’s wrong,” explains Jim Black. “What are we going to say to our kids, our grandkids, when they ask, ‘What happened around here? Why is this hole in the ground?’”

The Blacks say Lowndes never mentioned the quarry, but others saw it coming. Back in March 2007, the Orangeville Citizen printed an article headlined “Are Ontario potatoes turning to stone?” and calling the quarry plans “the best-kept nonsecret in Dufferin County.” Reporter Wes Keller had discovered that Lowndes’ brother David was applying for a gravel pit near Hamilton.

Lowndes neither confirmed nor denied an interest in aggregates, stating only his ongoing commitment to potatoes. This led the newspaper to publish a story confirming that potatoes were his only interest. Lowndes says he was open about the company plans if anyone asked during the sales negotiations, but Highland didn’t formally correct the published error until September 2008, when it sent a letter to Melancthon council announcing its plans to “explore additional land uses,” including wind and aggregates.

After buying the area’s two largest potato farms, Wilson’s and Downey’s, The Highland Companies invested millions in equipment upgrades. Photo by Tim Shuff

For Ron Speers, the announcement felt like a betrayal. Speers was one of the early sellers at the beginning of 2007. He ran a cow-calf operation on 300 acres. With $8,000 per acre seeming generous and no children to take over, it seemed like a good time to get out. The price of fuel and fertilizer was going up, the price of cattle was going down, and for the first time in his life he was borrowing money to pay bills.

“Nobody was supporting the beef or the farming industry, period,” says Speers. “I sold some calves for less than what dad was selling them for in ’79.”

There was no talk of aggregate and Speers didn’t ask – the sale documents referred only to agriculture. He signed but stayed in his house for another year. In that time, Highland came in and began clearing fencerows to facilitate the movement of machinery around its farms. However, the wholesale tree removal didn’t make sense to Speers, because trees break the wind and keep the soil from eroding. They also provide corridors for wildlife. Once the trees were gone, so were the deer he used to watch from his kitchen window.

(NDACT challenged the tree-clearing activity under the county treecutting bylaw, but failed to get the county on side.)

When Speers moved out, The Highland Companies tore down his house and his barn and all the trees planted around them – one of several house and farm demolitions that NDACT calls “rural blockbusting.”

Today, the Speers farm is a vacant knoll with a 360-degree view, the highest spot along Highway 124, bare in the heart of the proposed quarry. Speers moved out of the area and bought a 50-acre farm in Maxwell. “I feel sick when I drive down the road now,” he says. “I was there for 54 years. My whole childhood’s gone, something the whole family worked hard for.” He now says that if he’d known about the quarry proposal, he wouldn’t have sold.

With homes coming down, people moving away, and hard feelings about who sold or who did not, these are difficult times for the community around Reddickville, Honeywood and Horning’s Mills. Many are still looking back with bitterness, while The Highland Companies focuses forward.

Wind, rail, gravel and potatoes: the company says it is pursuing each as a separate, self-sustaining business. Of these, wind power is the least developed. The company says it’s researching wind but hasn’t reached any decisions. It is also pursuing plans for the restoration of the Toronto, Grey & Bruce Railway to Owen Sound for industrial transportation. Through its Highland Rail Group affiliate, the company has made an offer to purchase the Orangeville- Brampton Railway from the town of Orangeville for $7 million. The railway currently runs south from Orangeville to Brampton, and $2 million of the purchase deal is tied to re-laying track to the north end of Dufferin County.

Negotiations with the county, where Orangeville’s mayor and deputy mayor would normally vote on the issue, are now stalled by a court battle over the town’s potential conflict. It could be years before trains start rolling, but the company says that won’t stop the quarry.

Trevor Downey, now vicepresident of marketing and sales, says “We’ve got 8,ooo acres; 2,4oo may be subject to a quarry, but with rehabilitation that will allow for sustainability.” Photo by Tim Shuff

In all this, John Lowndes sits in the background. For any question or complaint about its operations, the public face of Highland nowadays is Michael Daniher, the company’s PR man. Daniher is the chairman of a euphemistically named Toronto public relations firm, Special Situations Inc., whose connections hint at the gravity of Highland’s political and professional resources.

Daniher’s business partner is Paul Curley, a former advisor to Prime Minister Brian Mulroney and other Progressive Conservative party leaders. He shares an office with two other agencies, Counsel Public Relations and Counsel Public Affairs. The latter’s president, Philip Dewan, previously the most senior political advisor to Premier Dalton McGuinty, is one of two lobbyists registered to work at Queen’s Park on behalf of The Highland Companies on issues of “agriculture, economic development and trade, energy, environment, transportation and natural resources.”

Today it is Daniher who sits at every council meeting on the company’s behalf and whose phone number appears on Highland’s press releases, letters and website. Into the buzz of NDACT’s accusations, Daniher is the beekeeper blowing smoke.

He is pleased to offer me a tour of Highland’s potato operation. Selling under the pre-Highland brand names of Wilson’s and Downey, potatoes are the one sure thing Highland has going.

Trevor Downey, whose family has farmed these lands for four generations, now works for Highland. He shows off some of the $4 million worth of new equipment that Highland has purchased in the last two years. “We’re challenged every day now for growth,” Downey says.

To meet the demand from big customers such as Loblaws, he needs a 12-month supply, which means importing millions of pounds from the southern U.S. to supplement Melancthon’s harvest. This is local food in the real world. A new deal with President’s Choice for six million pounds of yellow-fleshed russets, a specialty variety, has him travelling to Florida and California to find partners – or possibly buy more land.

In May 2007, Downey told the Orangeville Citizen that if he had thought Highland had any plans to develop aggregate, then he wouldn’t have taken his job. This spring he was promoted to vice-president of sales and marketing.

“We’ve got 8,000 acres; 2,400 may be subject to a quarry, but with rehabilitation that will allow for sustainability,” he says. “There’s also the opportunity to lease more land, purchase more land.” Presumably, for a man who farms the continent, 2,400 acres can seem like, well, small potatoes.

NDACT accuses Highland of using potato farming merely as leverage and cover for its quarry business, but I get a clear picture that this is one group of international investors who are serious about growing food, and are probably doing too well to give it up when the quarry goes in.

Potato farmer David Vander Zaag inspects the crop with three of his four sons: Eric, 13, Daniel, 7, and Ryan, 1o. The third-generation potato farmer moved to his 1,ooo acre farm (next photo) in Melancthon from Alliston, enticed by the perfect texture of the Honeywood silt loam. Photo by Bryan Davies

Maybe they will follow through on their objective to return the land to agriculture. Daniher explains that the quarry will only dig 300 acres at a time, and that it will be “progressively rehabilitated” back to cropland. Massive, ugly pits are old school, he implies. This one, to look at the pictures, will be green.

It’s compelling to think that we can have both the gravel and food from the same land, that our much-needed limestone can be painlessly extracted like a wisdom tooth removed under anesthetic. Amidst the shiny maroon Downey’s trucks, the whirr of processing machinery and new tractors, I find it hard not to be persuaded that the company just might pull it off.

“You have no idea how good this land is,” says David Vander Zaag. “Can they return this land to agriculture? I don’t see an argument that says they can.”

Vander Zaag is a potato farmer who moved here from Alliston and bought 1,000 acres. He came for the Honeywood silt loam, the area’s unique stone-free soil that’s just the right texture between sand and clay. That and the climate make this area perfect for growing potatoes.

“This area is the largest block of vegetable land in Ontario,” he notes. “Vegetable land is rare, only .0006 per cent of our province’s landmass. Why destroy it and put an open pit mine here?”

Preserving this land for agriculture is NDACT’s number one argument against the quarry. The group has been lobbying to have it designated as specialty cropland – a protective label attached to the Holland Marsh and the Thornbury apple-growing region.

Highland sharply criticized the tactic as “a blunt and dangerous instrument” that would threaten landowner rights. When the specialty crop designation somewhat curiously failed to win the support of the Ontario Potato Board, NDACT members noted that Bruce Wilson, Highland’s vice-president of farm operations, is one of the board’s directors.

That situation, along with questions about who called whom with regard to farm creditors, speaks to the worstcase fears of the independent farmers: that Highland has enough political connections, enough corporate diversity, and enough clout in the marketplace to afford to underprice its potatoes long enough to put smaller local growers out of business and buy their land.

NDACT has more than 1,000 local signatures on its petition to stop the quarry – a lot in a township of 2,800 – but the group suggests there would be a lot more if the area’s fertilizer dealers, equipment suppliers, insurance and real estate brokers didn’t all have some stake in Highland’s farming operations.

David Vander Zaag acknowledges the fears, but the father of four young sons prefers to frame the debate differently. In an e-mail following our discussion, he writes:

“This really isn’t about The Highland Companies or Lowndes’ business practices. They are just businessmen trying to make a buck.

“It is about land-use planning and what makes sense as a society and as a province. We are called to be stewards of our environment and that can’t be left to the forces of big business and big money influencing government policy. This is some of our country’s finest land and water resources. Stewardship is a responsibility passed from our forefathers and entrusted to us for our children.”

From the perspective of a quarry developer, Highland’s method of integrating itself into the community was a master stroke worthy of inclusion in business school textbooks, if its plans are successful.

Already, Highland claims to provide 24 per cent of Melancthon’s 289 jobs (of the 70 potato farming jobs, Daniher says about 10 are “new” positions) and to pay 25 per cent of its taxes. It provides a health and dental plan to its workers. The company’s press materials portray a community in economic crisis that badly needs the quarry’s 400 promised jobs. Every month or so, it announces a major donation: scholarships for high school students, $5,000 for the legion, $6,000 for the food bank, $10,000 toward the purchase of a Zamboni for the Honeywood arena, even the provision of housing for two new medical professionals, among others.

Underlying each is the unstated question: Where would you be without us? And every press release ends with a reiteration of the importance of “economic growth and diversity” to the sustainable future of Melancthon.

Highland says it will come out with a quarry application within the next few weeks that will include a site plan and answer all the questions about the pace of extraction, the tonnage removed, the truckloads per day, and every other detail currently subject to rampant speculation.

Signs like this one erected by the North Dufferin Agricultural and Community Task Force are starting to pop up around the countryside as NDACT focuses its opposition to the quarry around the protection of cropland. Photo by Bryan Davies

Then it will be up to Melancthon’s five-person council to decide whether to approve the required official plan and zoning bylaw amendments for the largest development the township has ever seen. So far, the part-time politicians seem to be scrambling in a game of catch-up behind the company and the citizens. Mayor Debbie Fawcett in particular drew ire for her apparent acceptance of the quarry before the application had even been submitted. “I don’t think we can stop it,” she told the Orangeville Banner.

In the meantime, NDACT will continue to fight Highland’s every move while building its case around the protection of cropland and, failing that, water. Precedents suggest that water will be the showstopper.

The province currently favours aggregate development over most other uses, including agriculture. The Provincial Policy Statement even provides a loophole that can exempt pits that penetrate below the water table from rehabilitation requirements. Even so, in two recent cases where quarry applications have been rejected or delayed, both were over water: the Flamborough quarry near Hamilton and the Rockfort pit expansion in Caledon. Both raise serious concerns about groundwater recirculation: precisely the type of water management system that Highland proposes to apply on a massive scale.

And NDACT members have carefully watched the highly charged controversy over Site 41 in Simcoe County, where water issues related to a landfill proposal have attracted national and international attention, and have recently resulted in that county’s council approving a oneyear moratorium on construction.

In Melancthon, Highland’s proposal includes digging well below the water table (which sits as little as three metres from the surface) – up to 250 feet below it, according to NDACT’s analysis. The company proposes to manage the resulting f looding with elaborate pumping, removing or injecting water into the ground around the quarry as required to maintain the current groundwater levels.

Garry Hunter, a hydrogeologist consulting for NDACT, is skeptical. He notes that the perimeter of the licensed area is 23 kilometres long and a waterproof barrier would have to be maintained around all of it. Something everybody is waiting to see in the quarry application is how exactly Highland plans to keep water out of a 250-foot-deep hole – forever.

The proposed barrier is the same type of technology that Caledon’s Coalition of Concerned Citizens is set to vigorously challenge when the Rockfort pit application goes before the Ontario Municipal Board this month.

If Highland’s plans affect water flows anywhere, it will be the upper Pine River, which emerges from the ground near Horning’s Mills, south of the quarry site, and cascades down the Niagara Escarpment through a forested valley. On a final visit to the area, I drive down this valley, pondering the theme of downstream effects, not just through space, but through time – for it is one of NDACT’s assertions that we must think in terms of both.

On the way, I stop by the riverside home of Rob Uffen, a stop-the-quarry activist who worries about the fate of the native brook trout he can see from his deck – swimming and breathing in water that originates somewhere in the middle of the quarry site.

“What will happen to the Pine River valley?” he asks. Uffen says the river is already low and traces problems back to the draining of wetlands and the clearing of forests for potato farms decades ago, and now the drawing of water for irrigation and nitrogen runoff. These are problems enough without a quarry, and they provide a snapshot of the larger environmental questions lost in a skewed debate that makes industrial agriculture look like the green alternative.

Further downstream, the Pine flows into the Nottawasaga. The Nottawasaga flows into Georgian Bay. I drive all the way to the mouth, imagining that I’m travelling forward in time, until I reach Wasaga Beach and lose track of the river as the highway fans out into its own obnoxious concrete delta of parking lots, strip malls and boat ramps.

So this is where all the stone ends up in our “sustainable future.” I think back to the Honeywood plateau, one thousand vertical feet upstream where green fields kiss the sky, and thank God we’re not there yet.

What's In A Name?

The High County, Dufferin Highlands, the Roof of Ontario.

All are descriptions applied to Dufferin County, where the roads may dip, but inevitably climb higher again, northward into the steep hills of Mulmur or onto the sweeping Dundalk plain in Melancthon, reaching the watershed at over 1,7oo feet above sea level before the land rolls back downward toward Georgian Bay.

Melancthon is the largest township in Dufferin County, but, situated in the far northwest, its fertile, windswept lands have until recently seemed exempt from the development pressures that dog the rest of the county.

Surveyed in 1853, it was named after a sixteenth-century German scholar named Philip Melanchthon. He had teamed up with Martin Luther to reform the Catholic Church. As the story goes, a Catholic surveyor, who had spent the summer in the mosquito-infested wetlands of west Dufferin, named that township Luther, “after the meanest man I know.” And went on to name (and misspell) the adjoining township “Melancthon,” as he said, after the second meanest man.

The story may be apocryphal, but is a reminder that it has never been easy to predetermine Melancthon’s destiny. In spite of its name, it was home to the first Roman Catholic church in Dufferin, and in the 1880s, when the vast majority of the county’s population were Irish and Lowland Scots, nearly half the settlers in Melancthon were of English origin.

Related Stories

Pit by Pit

Sep 20, 2022 | | EnvironmentAs another battle over aggregate mining gears up in Cataract, the question remains: how do we balance our voracious demand for aggregates with the rights of local citizens and nature?

Mega Quarry

Jan 14, 2012 | | Web ExtrasProtect Ontario’s land and drinking water, stop the Melancthon mega quarry. View Adrienne Arsenault’s report from CBC’s The National.

Birth of a Protest

Jun 16, 2011 | | EnvironmentThis spring, when The Highland Companies filed its application for a 2,316-acre limestone quarry, a small rural protest caught the big wave.

Melancthon Mega Quarry

by the Numbers

Jun 16, 2011 |

|

Environment

This spring, when The Highland Companies filed its application for a 2,316-acre limestone quarry, a small rural protest caught the big wave.

From The Coalition of Concerned Citizens (Nov 15, 2010) — The CCC has just learned that the Ontario Municipal Board decision regarding the James Dick Construction Limited Rockfort Quarry application for a license for an open pit dolostone mine at Winston Churchill and Olde Baseline in the Town of Caledon has been denied. The OMB decision is available online at: http://www.omb.gov.on.ca/english/eDecisions/eDecisions.html. CCC web site: http://www.coalitioncaledon.com/.

Diana Hillman on Nov 15, 2010 at 6:27 pm |

Rockfort Quarry update: Special OMB Public Hearing MON APR 12, 1-4pm and 6-9pm. Caledon Community Complex, Caledon East. For more information, see the Coalition of Concerned Citizens web site at http://www.coalitioncaledon.com/.

Online Editor on Apr 8, 2010 at 2:44 pm |

It is well known that the Highland Rail Group’s anticipated rail line through the Town of Orangeville will be used for transporting trains heavy with aggregate product from the Highland Companies’ proposed and unprecedented 2400 acres, 200 foot deep mine in Melancthon Township. Trains will travel through Orangeville south to Toronto and north to Owen Sound where gravel will presumably go on ships and out of Canada and the profits will go to a faceless Boston based hedge fund.

Orangeville citizens need to carefully consider what an active rail line, with a busy schedule, carrying heavy materials through their streets, many of which are residential, will mean to them as residents and business owners, and not get too excited when local papers claim “Victory” for Orangeville.

They might also consider that it is not a victory for their friends and neighbours who will live next door to a 2400 acre, 200 foot deep, air polluting, water sucking hole that rocks their world daily with explosives. It is simply one more link in a chain that brings rural Melancthon and the headwaters of Dufferin closer to possible destruction.

For those who think that this rail line needs to go to Highland Companies proposed, giant, gravel mine in Melancthon, because it must be necessary to supply Ontario’s (Toronto’s) insatiable thirst for gravel, think again. There are 7000 gravel pits in Ontario, and a recent State of the Aggregate Resource in Ontario Study noted that there are enough pits within 75km of Toronto to supply their gravel needs for the next 20 years, and then there are all the other thousands of pits outside of the 75km. Twenty years, without a giant pit in Melancthon, will give the Aggregate Industry adequate time and incentive to revamp how it does business.

The Toronto Environmental Alliance http://www.torontoenvironment.org strongly encourages the reduction, recycling and reuse of aggregate materials for the greater Toronto area and surrounding municipalities. Ever wondered what happens to giant skyscrapers and enormous bridges that are torn down? That cement can be recycled.

The Aggregate Industry is one of the most financially and politically powerful industries in the country. Check out http://www.gravelwatchontario.org. It is the ethical duty of the industry to invest in the reduction, recycling and reuse of materials rather than continue to devastate non-renewable farm land.

Perhaps the rail line will be good for local businesses but, I would like to know what written guarantees municipalities have that the train will even stop; when and how often? Won’t the Highland Companies main focus be to move as much product as quickly as possible through Shelburne and Orangeville to its southern market place and then back to the mine for more?

Certainly, a rail line might create new jobs by attracting new and powerful industry; perhaps an American based hedge fund will come and destroy thousands of acres of Prime Agricultural land and start a giant aggregate mine! What about small business? I have been told that a local business man, initially excited about the HRG, was disappointed to discover that it would increase his business costs significantly. What written guarantees has Orangeville Council made for fair freight rates, safety measures, and upkeep? It is true that trains are more environmentally friendly than trucks, but if they are loaded with a product that has irrevocably altered the environmental fabric of a neighbouring municipality and poses devastating water issues for a huge chunk of Ontario, then how will that help the environment?

And what about a passenger car? I am not really interested in taking a scenic ride with my kids on a train loaded down with thousands of tons of heavy rock product. And what possible future variables are associated with this line that might actually end up costing the tax payers millions in the long run? Wasn’t that why the trains were stopped in the first place?

Five million dollars, such as Orangeville bargained for, doesn’t seem to go very far these days and it makes one wonder whether the corridor property has been vastly under priced. Citizens need to ask all these questions and many more before they encourage their politicians to vote, or work to influence the vote of neighbouring municipalities. It is those municipalities who will pay the ultimate sacrifice and suffer a terrible loss of community.

Anyone wanting to experience that loss, which is so strongly felt in Melancthon Township already, need only join our bi-monthly council meetings: http://www.melancthontownship.com or attend an open public meeting of the North Dufferin Agricultural and Community Taskforce: http://www.ndact.com. NDACT has filled the Honeywood arena on three occasions in the past year with hundreds of citizens from many parts of Ontario who oppose the negative impact of this mine.

In a time of climate change, our political leaders must think past the almighty buck to increasing food and water demands, and world famine. We, in Ontario are not immune to these threats. Our children will pay the price for our lack of political will and vision. Prime agricultural land, like the exceptional Honeywood Silt Loam Soil that lies directly in the path of the proposed Highland mine will be desperately needed and must be protected. Its unique structure and draining ability allows for good food production even during climatic challenges. Even if you are a ‘nay sayer’ of climate change, it is a documented fact that our agricultural land is continuing to disappear at an alarming rate while demands for food supply continue to rapidly increase.

Highland Companies’ claims that they will farm (something) 200 feet deep in the mined land seem unrealistic; even a representative from the Aggregate Lobbyist Association (Ontario Sand, Stone and Gravel) has said that “yes” a lake is considered acceptable rehabilitation in lieu of agricultural. Some surrounding farmers are convinced that their farm land will suffer and may even be lost, as huge amounts of water give over to gravity and drain into the 200 foot depth of the Highland mine making food production improbable.

Water, our most precious resource must be our first concern. Over one million Ontario residents depend on the water which flows from the Headwaters now mapped and proposed to be heavily and deeply excavated by Highland Companies. The Source Water Protection Act of this Province dictates that “activities that are or would be a significant drinking water threat either cease to be or never become a significant drinking water threat”, and the same Act “provides Municipalities with additional authorities to regulate any activity that is a significant drinking water threat”.

Our politicians must pay close attention to this Act and lean on it to insure the protection of the Dufferin Headwaters for all of Ontario. If not, County tax payers might find themselves paying in perpetuity to maintain the giant pumps (proposed by the proponent) to control the headwaters long after the Highland Company has finished mining Melancthon.

All of County Council, including Orangeville, must research the Highland Companies plans with great diligence and get expert advice from unbiased planners, engineers, and environmental experts, before they attempt to influence surrounding Municipalities to cast their vote for this rail line. It is sensible to assume that the rail line is contingent on the success of the Aggregate Application, and in turn one might assume that the successful bid to lay track may influence the success of that application.

No one in the County of Dufferin should be wishing this mine upon their friends in Melancthon. Here, citizens have already suffered loss of homes and health playing host to 120 wind turbines, and now we have been devastated by the loss and/or destruction of nearly 20 homesteads, thousands of trees, wildlife, and severe erosion of precious agricultural land, not to mention the erosion of our tax base as Highland Companies’ continue to ‘do business.’ All this, and an aggregate application has yet to be submitted!

I may be saddened by the judgment that allows Orangeville a vote on this matter of the rail line, but I do not necessarily disagree with it. However, my consensus on this is contingent “not on the colour of their money, but on the content of their character”. That content must include intelligence, a vision for the future, ethics beyond reproach, and above all else – backbone.

Should we worry about the character of these County politicians? Well, Orangeville reps did fail to have the foresight to consider ALL of the citizens of Dufferin County when they struck this financial agreement with the HRG in the first place. Not only did they fail to recognize that they had County responsibilities to consider, but they also failed to recognize that they were in the driver’s seat. They could have made that deal and kept all their citizens happy by taking the wheel and setting the terms. Since the Highland Rail Group had an extra $2 million to spend, the deal should have been $7million-not $5 million. And it should have been made very clear, that if HRG ever asked Orangeville Politicians to influence the vote of neighbouring municipalities (who are, after all, their County charges and friends) again – the deal was off! But, that didn’t happen. Yeah. We should all be worried.

Marni Walsh on Feb 15, 2010 at 9:48 pm |

I wish you would send a copy of your letter to the Mayor of Owen Sound. She was recently heard to say that this railroad might be a good thing for Owen Sound. It’s now July 21 2011 and we are still fighting and will be for as long as necessary. God Bless Louisa McCutcheon

Louisa McCutcheon on Jul 24, 2011 at 3:14 pm |

The Melancthon Graveyard.

Should the proposed open pit mining project in this community be authorized, then it is inevitable that depopulation will result. It will become the death knell for Melancthon.

The pursuit of the almighty dollar in this greed-driven society always takes precedence over the welfare, and human rights, of people and the value of the existing culture.

Melancthon has been growing top quality crops in its fertile soils, soils that are ideally suited to the production of potatoes. Beneath these fertile soils lies a huge deposit of sandstone that has drawn the attention of those who see its monetary value, but not its importance to the provision of filtered and potable water, water that feeds the wells of the local community. Remove the sandstone and you destroy the community. Municipal water would have to replace the contaminated well water and those left dry by the excavation.

The cost of the infrastructure needed to provide municipal water to all residents would be astronomical and few in the community would be financially capable of meeting the cost. It follows that, should the unthinkable occur, the Highland group of shareholders should be held responsible for the costs of materials, installation and the labour required to provide the municipal water.

Those holding shares in this business of tearing apart a community, one that serves the food requirements of many people, are, probably, unwittingly participants [that could be perceived as verging on] a criminal act. Should the final decision eventually be that of the Ontario Municipal Board, then, in all probability, the process of dismantling that community will be approved. OMB always seems to rule in favour of business; it has tunnel vision and focuses, usually, on business and jobs, plus tax revenues rather than the human consequences of the decision.

Should approval to excavate be received, it is unlikely that more than 120 jobs will be created, and those only for the time required to remove the sandstone. The local farming people will not be the beneficiaries of those jobs because most sold out to Highland because they wished to retire. Most would not have accepted the tempting financial offer from Highland had they been aware of the destruction that was planned. They know once the land is destroyed by what is planned by Highland, it will never recover. They believed the promise that the plan was to build a major world-class potato operation and that convinced them to accept the $8,000 per acre offered.

The negotiations to purchase the rail and to extend it to locations where deep water can accept shipping capable of transporting the sandstone to distant markets is also rumoured. If true, it would see the sandstone sold to the most lucrative markets, benefiting only the shareholders, not the province or the local people..

This assault on a spectacular environment and a successful farming area, the habitat of numerous indigenous creatures, and the lives of the local people must be denied by the elected authorities before it becomes too late.

K.Mesure.

[Received by email]

admin on Sep 22, 2009 at 10:55 pm |