Bringing ‘The Word’ to the Wilderness

Of the worshippers in Mono Mills he complained, “When they should rise, they sit; when they should sit, they continue standing.”

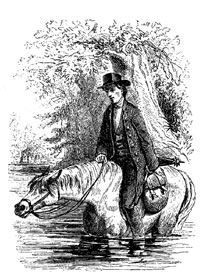

Clergymen who rode into the bush in the early days of settlement were called “saddlebag preachers.” With little more than a Bible and a powerful belief in their purpose, they roamed these hills to bring religion to the pioneers.

Catholic missionaries were the first Europeans into the bush in Upper Canada long before it was settled, but their aim was to live with the Natives and convert them.

Two centuries later, the saddlebag preachers proselytized to people who were already Christian but who were too few and too scattered throughout the wilderness to have a community church. So these clergymen were circuit riders, travelling from one log cabin to the next, preaching, baptizing, marrying and reassuring courageous pioneers that neither their church nor their God had forgotten them. The Methodists originated the idea of the circuit clergy in the U.S. and spread it into Canada. Thanks to the famous John Strachan, Anglican clergy were right behind them, especially in these hills.

As early as the 1820s, Strachan had realized that although the settlers here desperately wanted religious services, the population was too sparse for churches. He also realized that if the Church of England didn’t recruit circuit preachers fast, the Methodists would fill the gap. One of his first successful protégés was the sturdy and devoted Reverend Adam Elliot.

Religious Feelings a Two-Way Street?

According to historian Perkins Bull, the first teacher in Mono Mills was a Catholic who received the following instruction from the locals: “You are not to teach the children any of your Roman numerals. The Protestant figures are what we want.” Perkins Bull also tells of an unnamed Catholic farmer in Peel who, when asked what he’d do if there were no Roman church, replied he’d be an Anglican. If that were not possible, the old-timer allowed he might become a Presbyterian. “And if that were not possible, would you be a Methodist?” his questioner continued. “I’d die first!” was the reply.

So much to be done

From 1833 to 1836, Elliot travelled day after day from the southern reaches of Peel, through Dufferin and Simcoe, and as far north as Penetanguishene (where the French Catholic population formed a psychological, if not a logical border).

His experience was typical of the saddlebag preacher: lonely travel in all kinds of weather, overnighting with families in log cabins, sharing their fare, and wherever he stopped, offering religious service.

In March 1833, for example, when he arrived at the Cobean home in Mono, the word went out and neighbours flooded in. Many were Presbyterians, but so strongly did they miss the power of religion that any (Protestant) denomination would do. In a single day there, Elliot held a prayer service and a funeral, and performed two marriages and eighteen baptisms.

Although he was told there were not enough people in Mulmur to make a trip worthwhile he went anyway and this time 50 people mustered for a service where he did 12 more baptisms.

In 1834, Elliot reported preaching in a barn in Castlemore during January and then in a clearing in April, near present-day Caledon East. In October, he preached in Bolton, with the worshippers snuffling and sneezing because they were sitting on a barn floor where threshing had just been completed.

He then spent time in Orangeville and Albion before moving north and east beyond Newmarket. At every stop there were lineups for communion, marriages and especially baptisms. Elliot spent his last full year in these hills in 1835. By that time there were more preachers on the circuit (especially Methodists, causing Elliot mild annoyance with the Anglican hierarchy for being too slow to send him help), so he left the hills to spend the rest of his life preaching to Ontario’s Native people.

When Duty Calls

In 1856, Rev. Joseph Hilts of the Methodist Episcopal Church was riding a former circus horse to a service in Garafraxa. The horse’s sole gait was a trot, which it preferred to do in circles, so riding him demanded attention. Once, when Rev. Hilts was distracted as he bellowed out a hymn, he was suddenly tossed into a mud hole.

Undaunted, he immersed himself in a nearby stream, remounted the horse and, a few miles later, gave another service, still dripping wet.

Life in the saddle

Rev. Elliot was an intrepid worker and in his extensive reports he never once complained about what must have been extremely challenging conditions. This was not the case with one of his successors, William Darling. Born into a Presbyterian family, Darling became an Anglican (like John Strachan) and in the late 1830s was “saddlebagging” between Tullamore and Mono Mills.

Darling’s writings reveal a somewhat cranky nature, but perhaps a more honest description of what things were like for the men who preached in the bush. One thing that disturbed him was the pioneers’ ignorance – or lack of concern – for ritual. Of the worshippers in Mono Mills he complained, “When they should rise, they sit; when they should sit, they continue standing.” And when he administered Communion, he was horrified to find the vessels were “a black bottle and an old tumbler.” Darling also had little good to say about the church buildings that had begun to spring up in his time, calling them “remarkable specimens of ugliness.”

Darling’s frank reports include accounts of what it was like to bunk with his congregation in their one-room cabins. Like all saddlebag preachers, he could choose to sleep on the ground, in a barn or – probably the most sensible choice in winter – with a family. On one occasion he describes going to bed fully clothed in a Caledon home because the family had stayed awake to watch him undress.

Competing for souls

Darling’s candid observations refer to yet another gritty reality: Old-World religious quarrels were alive and well in Canada. Catholics, of course, were a front-line target. Residents of Mulmur and Mono were noted for making it clear that Catholics would be much happier if they settled elsewhere. When Darling wrote that he observed “downright uncompromising hatred toward Papists, rebels and other enemies” in these hills, he was underlining a political fact of his day.

Although the 1837 Rebellion was over, the issues that prompted it were still unresolved. The wealthy class in Upper Canada, the notorious “Family Compact,” was still very much in control. They were mostly Anglican and, to a lesser extent, Presbyterian. The “rebels and other enemies,” as Darling refers to them, were adherents of other religions. To him, these people, especially the Methodists, were potentially dangerous.

The Methodists were a thorn in the side of the Anglican and Presbyterian hierarchies for another reason. Those two religions were established and ritualistic, while Methodist preachers leaned toward revivalism and emotion. To early settlers, weighed down by the drudgery of survival and loneliness, whooping it up at a camp meeting probably had more appeal than sitting demurely through a ritualized church service, and that may be one of the reasons the four branches of Methodism outgrew all others in these hills.

Records for East Garafraxa in 1852, for example, show 479 Presbyterians, 457 Anglicans and 163 Methodists (65 professed other religions, with just one Catholic). Twenty years later, when the township population had more than doubled, the Anglicans had grown by 10 per cent, the number of Presbyterians had slightly more than doubled, while the Methodists had quadrupled. (And there was still but one Catholic.)

By that time, the saddlebag preachers were gone, and among the trees where they had once prayed and preached stood solid brick churches. Adam Elliot, who first rode into these hills in 1833, lived long enough to see this dramatic change. And even though the Methodists appeared to be in the lead, it must have given him great satisfaction to know the hardship he endured to bring “The Word” to the wilderness had been worth the effort.

My Church and No Other

When the Anglican saddlebag preacher, Featherstone Lake Osler, came to Bolton in 1838, he was greeted by an elderly man named Pringle who declared with tears streaming down his face that over 20 years of pioneering in (what is now) Peel, he had seen the face of a minister only four times. Records show that Methodist preachers would have crossed Mr. Pringle’s path at least several times a year in that time. Obviously they didn’t count.

Featherstone Lake Osler (1805–1895, the father of Sir William Osler) was a popular saddlebag clergyman who not only preached on the circuit but pulled teeth. He gave a stained glass window to the Christ Church congregation in Banda at the north border of Mulmur around 1865. It is now in the current church, built c.1897.