Exotic Species aka Mantis and Honeybee

What has our impact been on native North American wildlife? I think we know the answer to that.

Recently I spent some idle moments adrift in a sea of asters and goldenrod. The purple and yellow of these flowers beckoned not only me, but a host of pollinating insects. The autumnal meadow hummed with the beating of their tiny wings.

Honeybees were abundant, gathering food stores to see them through the winter. One at least, would not make it back to the hive. It landed on the golden centre of a New England aster, but then, in a twinkling, was seized by a praying mantis.

The mantis held the bee in an impressively spiked forearm. And though the bee worked her stinger in and out, the potent weapon stabbed only air. In mere minutes the mantis consumed the entire honeybee, including her wings.

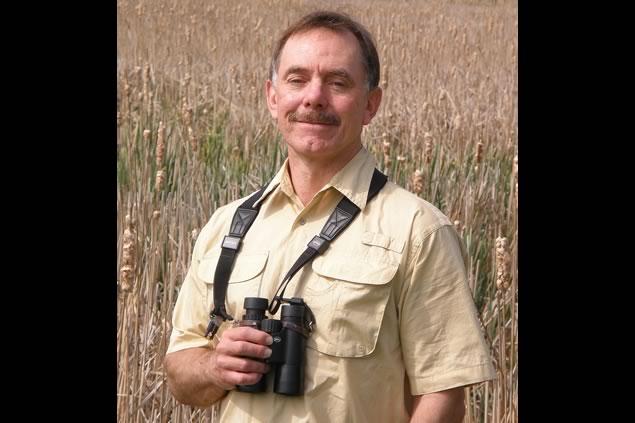

Thinking about this incident afterwards I pondered the juxtaposition of the three actors in this drama. All of them, including myself, were of European origin.

Honeybees (“white man’s flies”) arrived with French and English settlers five hundred or so years ago and enjoyed a reprieve from mantids until those fearsome predators caught up with them in the late 19th century. As for me, my forebears arrived from Europe in the late 19th century as well.

Introduced animals, often referred to as “exotic species”, have varying effects on native North American wildlife. Some, like praying mantids, seem to cause barely a ripple.

Other introduced animals and plants make a much larger splash – often creating waves that sweep away native species. Even the honeybee, considered by most as a welcome addition to our fauna, has been accused of hurting our native pollinators.

And what about the vast majority of us who also qualify as “exotics” because our ancestry can be traced to other parts of he world? What has our impact been on native North American wildlife? I think we know the answer to that.