Dufferin Eco-Energy Park

While landfill raised concerns about what was seeping into our ground and water, gasification raises concerns about what is seeping into our air.

TRASH TALK: Dufferin County has some high-tech trash plans. Are they forward-thinking or foolhardy?

Back in the mid-’90s, I had a crazy idea. I wanted to learn about local politics, so I applied to be a citizen member of Dufferin County’s Community Development Committee.

One of the committee’s primary responsibilities was to oversee Dufferin’s proposal for a new landfill. It was in the final stages of approval after millions of dollars of study and years of enraged debate. A naive keener, I read through a foot or two of reports, then marched off to my first meeting – and into a hornet’s nest.

Despite its pending approval, the new landfill continued to face fierce opposition, and this bunch played rough. At that first meeting, I learned how the audience would boo vigorously if you said something they didn’t like. At the second, I learned how to make a county councillor froth at the mouth, and how to land myself on the front page of the local paper. After the third, it was ugly phone calls to my home – between the f-bombs was something about how my face might be about to meet a fist.

So it went for my two-year tenure. The politicians were at each other’s throats. The public opposition groups were at everyone’s throats. County staff ducked, bobbed and weaved like seals in mating season.

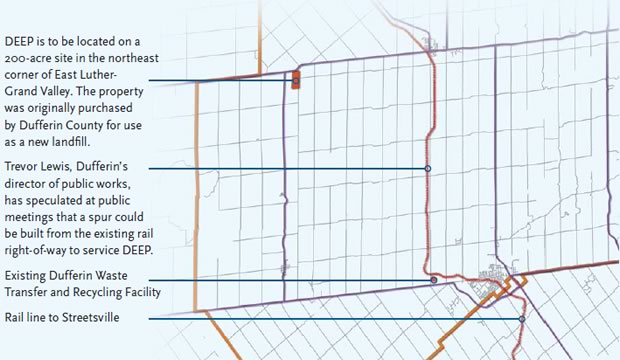

Some 15 years later, the Community Development Committee is still debating garbage, and what to do with that 200-acre landfill site the county owns out in the northeast corner of East Luther-Grand Valley. It’s a miracle there hasn’t been a lynching.

I must admit it’s also near-miraculous how the discussion has evolved. The once certain-seeming landfill eventually received environmental assessment approval and a Draft Provisional Certificate of Approval, but by then its opponents had sufficiently infiltrated local politics. The proposal was quashed, and the new dump was never built. In its place are plans for an industrial subdivision of sorts, the occupants of which will be mostly engaged in the generation of energy from waste. It’s called Dufferin Eco-Energy Park, or DEEP.

Is DEEP a sensible, pioneering investment, or a nimby-maniacal, anything-but-the-dump reaction, destined to be a hugely expensive white elephant?

As envisioned, DEEP will tackle the ever-growing mountain of garbage Dufferin residents produce from a number of different angles. Perhaps the most ambitious component of DEEP, and the anchor for everything else, is an energy-from-waste, or EfW, facility that will employ a technique called plasma gasification. The plant will process what remains after recyclable and compostable materials are removed from the waste stream, by vaporizing it at temperatures roughly as hot as the sun.

Dufferin Eco-Energy Park, or DEEP to be located on a 200-acre site in the northeast corner of East Luther-Grand Valley.

Assuming it all works, almost none of the by-products will go unused. Combustible gases produced in the process will fuel a turbine to generate electricity, which in turn will be sold to the grid. Waste heat from the process will provide a cheap source of heat for a greenhouse operation or other businesses located on site, and if it is deemed suitable, the hard, glass-like slag residual would be used in road and construction projects.

The facility won’t be the only EfW plant handling garbage produced in Headwaters. The Region of Peel opened a conventional incinerator in Brampton in 1992, and it currently processes about 175,000 tonnes a year, including waste from Caledon. Owned by Algonquin Power Systems, the plant is operated under a long-term waste supply agreement with the region.

In a similar arrangement, Dufferin County has entered into a Memorandum of Understanding with a Calgary company called Alter NRG, through its Ontario spinoff called Navitus Plasma Inc., to develop its facility.

A feasibility study assessed the possibility of building a plant with a 25,000 tonne per year capacity – enough to handle just Dufferin’s waste – but found the volume too small to be economically viable. A 70,000 tonne per year capacity did look like it would work, and even though it meant importing significant volumes of trash, Dufferin County council agreed to proceed. In the company’s most recent submissions, the volume has been increased again, to 89,000 tonnes a year. Navitus CEO George Todd says this second increase was also a matter of economics.

Supporters claim the plasma approach is clean, makes use of a large renewable energy resource, and promotes sustainability. But critics aren’t so sure. In their view, there aren’t yet enough data to support such claims.

So let’s take a look at some of the evidence for and against.

On the bright side

It has to go somewhere

According to Peter Hargreave, director of policy and strategy for the Ontario Waste Management Association, the province generates about 12.5 million tonnes of garbage each year, or roughly one tonne per person. About 4 million tonnes are exported to Michigan and New York, most of it from the industrial/commercial/institutional sector.

However, our American neighbours are growing increasingly testy about us using their backyard as a dump, and there are strong indications that the border will eventually be closed to Canadian waste altogether, or become prohibitively expensive.

Without the U.S., Ontario’s annual maximum permitted fill rate is not sufficient for the waste requiring disposal. What’s worse, even though some new capacity has been approved in the last few years – mostly by expanding existing sites – space is running out fast. As a result, EfW facilities are expected to become more common.

In 2009, after recycling and composting, Dufferin County was generating about 15,000 tonnes a year requiring disposal. Most of that was shipped to the U.S.

What you get: No landfill

Dufferin’s approved-but-never-opened landfill site becomes more valuable by the day, to both the private and public sector. As Allen Taylor, mayor of East Garafraxa and chair of the county’s Community Development Committee, says, “People will be walking in here with a blank cheque and saying how many million do you want?” The City of Toronto did just that when it bought a licensed landfill near London, Ontario several years ago.

Building an alternative form of waste disposal on Dufferin’s site would preclude a landfill from happening there.

Points for trying

When Dufferin decided to trash its landfill plans in 2000, it committed to finding an alternative way to handle garbage. An exhaustive review of the available options was undertaken, and finally, in the fall of 2008, it issued a Request for Proposals to design, finance, build, own and operate a thermal treatment waste processing facility. Alter NRG’s plasma gasification proposal was accepted in 2009.

In short, the county took its time, considered the alternatives, and plasma gasification is where it ended up.

There is some track record for plasma gasification

According to Allen Taylor, “There’s a lot of untried technology out there. They’ll say ‘Oh yeah, we can do it for ya,’ but you just try and find a demonstration plant that shows they can.” Alter NRG backed up their technology with two reference plants in commercial operation in Japan. A contingent of six committee members visited them last fall, and came away impressed.

The residual isn’t too nasty

Though estimates vary, somewhere between 5 and 20 per cent of the waste fed into the gasifier will come out the bottom, transformed into a glass-like residual. Tests to date in the U.S. and Japan indicate this slag is an inert material that may be suitable as aggregate in road building and concrete.

Though it’s a somewhat different material, Peel Region has been testing ash produced at its incinerator in road and parking lot asphalt with positive results. Brampton Brick has also been experimenting with using it in brick making.

However, the Ministry of the Environment will need to be convinced Dufferin’s slag is inert, and the Ministry of Transportation would require lengthy testing before it could be used on provincial roads. But Trevor Lewis, Dufferin’s director of public works, points out the county builds and maintains quite a few roads of its own: “We’re also a buyer of those products. I would propose that we do some test strips using the slag to see how it works, and if things work out, here’s a way to get rid of it.”

In any event, Allen Taylor insists, “The deal we have with Navitus is that the residual is their problem, not ours.

At the end of the day, that residual is part of what Navitus contracts to deal with.”

Limited taxpayer investment

A White Paper produced by the Town of Mono’s Sustainability Advisory Committee makes a convincing argument that, based on the experience at other gasification and incineration plants, the cost of the EfW facility could easily be double or even triple the roughly $70 million estimated in the Navitus feasibility study.

However, Dufferin officials point out that for county taxpayers the capital cost of the facility is somewhat irrelevant. “We’ve said from day one that it’s a design, finance, build, own and operate by Alter NRG/Navitus,” says Allen Taylor. “Dufferin County has never committed itself to a dollar toward the building or operation of this facility. Nobody has even suggested to us that we co-sign a loan.”

So where is the money coming from? Says Taylor, “These folks are out dealing with pension funds and other investment institutions trying to sell them a piece of the action for a guaranteed return on their money.”

Still, the original Memorandum of Understanding in 2009 called for an acceptable financing structure to be in place by the end of that year. Taylor says the delay is related to the slow progress on provincial environmental approvals and power rate negotiations. Investors aren’t likely to commit without those assurances, which are now not targetted to be in hand until the end of this year or early next.

It’s cheaper than recycling

Sadly, as Allen Taylor notes, “Composting and recycling are the most expensive ways you can deal with waste. If people understood the real cost of recycling, they’d be amazed on a per-tonne basis.”

Recent county studies peg the cost of recycling at $209 per tonne. Turning source-separated organics into compost costs $115 per tonne, plus the cost of collection. The target rate for tipping fees at the EfW plant is $100 per tonne.

Relief from sheer exhaustion

Dufferin began trying to address its waste problem nearly three decades ago – longer than the projected 20-year lifespan of the EfW plant. It could go on considering alternatives forever. If the issue is ever to be resolved, at some point concrete decisions have to be made.

But then again

Consume, consume, consume

Zero Waste philosophy promotes the rethinking of product life cycles so all components can be reused. Possibly the worst strike against the EfW plant is that it perpetuates the endless cycle of pulling resources from the earth, spending vast amounts of energy processing them in factories and shipping them around the globe, where they end up lost – buried in a landfill, burned or “thermally treated.”

While generating electricity recovers some of that energy investment, it’s only a small fraction. However, the technology does appear to be improving. Peel’s conventional incinerator delivers about 6 MW to the grid. Dufferin’s plasma gasifier is predicted to net out at about the same, from only about half the volume of waste.

How many Rs do you see?

We’re all familiar with the three Rs: reduce, reuse, recycle. Proponents of gasification would have us believe there’s a fourth R: recovery, and that creating energy from waste does just that. However, the fly in the ointment is that this fourth R works against the other three. Once you’ve built the facility, it has to run pretty much at capacity to be financially viable. As a result there’s an obvious disincentive to reduce the volume of material available to feed the monster.

Alter NRG and the county have agreed to “high grade” the waste feedstock to boost the BTU content, using things such as scrap tires, carpet remnants and unrecyclable plastics. This will not help such efforts as the Ontario Tire Stewardship’s initiatives to develop markets for recycled rubber products, or other recycling research programs, such as Peel’s partnership with a private company to recycle carpet.

The province has tried to address this problem by insisting on high waste diversion rates before it will issue a certificate of approval for new EfW facilities. The Region of Durham, for example, had to commit to at least 70 per cent diversion before they could go ahead with the new conventional incinerator currently under construction there.

Similar levels are predicted for Dufferin, but there’s a long way to go to meet that target: the diversion rate currently stands at 36.5 per cent. It remains to be seen if other municipalities would also have to meet those targets before their waste could be shipped to Dufferin.

More expensive tipping fees

The typical tipping rate municipalities pay for landfill is $75 per tonne. The target rate for the DEEP EfW is $100 per tonne, and it’s possible that by the time final design is complete this will increase. Trevor Lewis says, “The feedback we got from the local municipalities was that they didn’t mind paying a premium for something that was going to be more environmentally friendly, which we feel this technology is.”

But how much of a premium is that likely to be? The Mono committee’s White Paper argued that the company’s financial projections failed to include several capital costs, including such critical components as wastewater treatment and disposal. Ed Kroeker, an environmental engineer and chief author of the White Paper, says, “So what if maybe up front these guys pay for everything? We’re still going to pay for it. This isn’t a charitable donation from Alter NRG to Dufferin County. It’s the old saying ‘You can pay me now or pay me later.’ Once the music starts the piper has to be paid.”

So much for “Dispose of your waste in your own backyard.”

In the 1990s, a central mantra of waste disposal was “dispose of your waste in your own backyard.” In other words, to avoid the environmental and financial costs of shipping waste hundreds of miles, municipalities should deal with their own waste within their own borders. At the time, with that very principle in mind, Dufferin’s neighbour, Simcoe County, passed a bylaw declaring all its waste must be disposed of within Simcoe.

Even in 20 years, Dufferin’s garbage will only account for 15 to 20 per cent of the volume proposed for the DEEP EfW facility (less if 70 per cent diversion is mandated as predicted), with the balance imported from other municipalities.

Trevor Lewis agrees that Dufferin will account for only a “very small percentage,” but he says that’s because “we can’t find the technology to treat just the small quantity that we have on our own.” Allen Taylor qualifies that by adding, “Within the price range we’re willing to pay. You could build a facility to handle just Dufferin County. We just can’t afford to pay what it would cost to do that. It’s a matter of economies of scale.”

Which raises another question: Why not locate the EfW plant where there’s a bigger population, and export Dufferin’s waste there, instead of the other way around?

Lewis responds, “Somebody has to do it. We’ve got the land, we’re looking for alternatives, let’s try something rather than just twiddling our thumbs.” And in Taylor’s view, Dufferin’s small size and comparative lack of bureaucracy make the project more achievable. “Sometimes you can do something on a small scale that you couldn’t do on a big scale.”

Trevor Lewis also sees Dufferin’s plant as the first step in a grander scheme. “What I like to suggest is we get the thing running and we’re doing a great job, then bring the City of Toronto up to show them what they can do. The place for this type of thing is actually industrial subdivisions in Toronto. Then they’re not hauling the garbage as far, the grid’s right there, and how much of that energy could they use right on the site?”

Simcoe County, meanwhile, failed in its efforts to open a new landfill at its infamous Site 41, and has recently rescinded its local disposal bylaw. Although Navitus, not Dufferin, is responsible for sourcing contracts, county officials have teamed up with the company and made presentations to Simcoe, aimed at securing some 47,000 tonnes of its waste to feed the DEEP plant.

Which way to the toxins?

While landfill raised concerns about what was seeping into our ground and water, gasification raises concerns about what is seeping into our air.

The European Commission’s Integrated Pollution Prevention and Control Reference Document on the Best Available Technologies for Waste Incineration (2006) found that air emissions from conventional gasification installations are the same as from old-fashioned incinerators. Among the nasties: particulate matter, volatile organic compounds, heavy metals, dioxins, sulfur dioxide, carbon monoxide, mercury, carbon dioxide and furans. Even tiny amounts of some of these substances, such as mercury, are harmful to human health and the environment. Dioxin, reported as the most carcinogenic known substance, has no safe level of exposure.

However, the industry argues that because plasma gasification heats the waste to much higher temperatures than conventional gasification or incinerators, most of the toxins are destroyed. Those that remain, as in the conventional process, pass through a series of pollution control devices that capture and concentrate them for disposal as hazardous waste. As a result, Alter NRG, and the rest of the industry, forecast emissions to be less than from a natural-gas-fired plant generating the same amount of electricity. Proponents further argue gasification is not incineration, and because there is no combustion, no combustion gases are released.

If they’re right, it’s a compelling argument in favour of plasma technology. However, regulators have yet to be convinced. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency continues to define it as a form of incineration. And in its regulations for “thermal treatment facilities,” the Ontario Ministry of the Environment makes no distinction between incinerators and conventional or plasma gasification.

The environment ministry would set maximums and monitor emission levels from the plant. However, its monitoring guidelines are based on a principle called “maximum achievable control technology,” meaning allowable emission levels reflect what is technologically feasible, rather than what is proven safe for the environment. And even these may be behind the times. With upgrades, the 20-year-old Peel EfW incinerator, for example, boasts emissions levels “well below” MOE standards. In addition, as the Global Alliance for Incinerator Alternatives points out, the standards only regulate a handful of the potentially thousands of pollutants that could be present in municipal solid waste, and they don’t consider the possible cumulative effects of exposure to multiple chemicals at the same time.

Finally, there are reports of explosions at EfW plants. Even if the chances are remote, should a catastrophic failure take place, an undetermined release of toxins could occur.

Will the darn thing work?

There are numerous examples around the globe of EfW facilities malfunctioning, undergoing lengthy or permanent shutdowns, or failing to produce the volume of electricity originally claimed. Plasma gasification has been around for two decades, but primarily in industry-specific applications. Its track record for dealing with the complex stew that makes up municipal solid waste remains very limited.

Navitus and county representatives point to the two operating plants in Japan as proof the company has the technical knowledge and operating experience to ensure that Dufferin’s facility will work. Those plants opened in 2003 and employ the same Westinghouse plasma technology.

But considering Alter NRG, Navitus’s parent company, didn’t exist until 2006 when it bought the rights to the Westinghouse technology, its claims of experience seem somewhat exaggerated. The Japanese operations are independently owned, with Alter NRG providing technical support and torch parts. In fact, the only plant Alter NRG owns and operates itself is a pilot facility in Madison, Pennsylvania, used for short, small volume test runs.

No matter, insist county representatives. The contract is to design, finance, build, own and operate. Dufferin will just be a customer that sends its waste there and pays a tipping fee, like any other municipality. And if the plant is temporarily shut down, Navitus will be responsible for finding an alternative place for the garbage to go.

In a worst-case scenario, if the operation were to completely fail or go bankrupt, Trevor Lewis says Dufferin’s liability is limited: “It’ll be on our land, so we’ll have to deal with it from that perspective. Do we want to go in there and run it, or try to figure out what could be fixed? Or is it just a matter of they walked away, we’ve got a new building, we’ve got some equipment inside, we have a garage sale.”

Perhaps, but as the entire DEEP project is envisioned, other businesses at the site will rely on the heat output from the EfW plant. If it goes down, the whole development could be in jeopardy. Dufferin would also be back at square one as far as dealing with its garbage, but the townships’ landfills will have all been closed.

Whether you think energy from waste initiatives are mean or green, chances are you will be seeing more and more of them in Ontario over the coming years. Already, the city of Ottawa has given its approval for a plasma gasification plant to proceed, a similar proposal is moving forward in Meaford, and Waterloo and other Ontario communities are considering the possibility. Proposals are also popping up across the United States, including the world’s largest plasma gasification unit, set to process more than 3,000 tonnes a day, under construction in St. Lucie, Florida.

Opposition in Dufferin has been very clear landfill is not an option. So something has to take its place. Like many municipalities throughout North America, Dufferin has turned to gasification as an alternative.

Is plasma gasification the waste-slaying, energy-generating pot at the end of the rainbow? Or is there still an alternative out there that would save headaches, perhaps even money, in the long run? With the huge pressure to resolve the global waste problem, the industry is evolving quickly, and it’s quite possible that over the next few years a better solution will come along. But after nearly three decades of anguished deliberations, and more than three years and few hundred thousand dollars into the current plan, Dufferin is running out of time.

Sometimes you’ve just got to pick the lesser evil. The trick is to know which one that is.

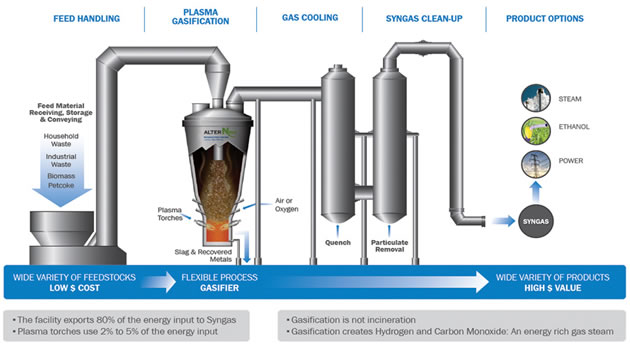

Plasma gasification

Dufferin’s chosen supplier for the EfW facility is a Calgary-based company called Alter NRG, which plans to employ a technique known as plasma gasification. Alter NRG has since formed an Ontario company called Navitus Plasma Inc., which hopes to develop and operate several similar facilities across the province.

While traditional incineration is, simply put, burning garbage in a big fire, gasification is the process of applying either oxygen-starved heat (greater than 7oo°C) or intense pressure to any material, causing it to separate into its basic molecular components. This produces a gas called syngas, which can be used to fuel engines that generate electricity.

There’s nothing new about gasification, which has been in use around the world since the 1800s. Plasma gasification, however, is more recent. This approach operates at much higher temperatures than conventional gasification. Torches inject plasma gas at over 5,ooo°C into the bottom of a chamber to maintain a +1,3oo°C environment. Waste is fed into the chamber and as it breaks down, most of it becomes syngas, exiting through the top where it undergoes a cleaning process, ensuring purity levels sufficient for use as fuel. Metals can be separated and recovered, and the remaining material melts into a slag at the bottom.

The chief advantages of plasma over traditional gasification and incineration are said to be reduced toxic emissions, and the ability to better handle a more varied feedstock.

Renewable power?

The Navitus feasibility study identifies electrical power generation as a significant income stream for the plant, forecasting a gross output of 9.3 MW before power used in the process is subtracted, and approximately 6 MW net available for sale to the grid.

The study anticipates receiving 12 cents per kilowatt hour (kWh) via a Power Purchase Agreement from the Ontario Power Authority. So far, however, the province has only offered eight cents. This is because EfW facilities are not considered a renewable energy source, so the price offered is similar to other non-renewable forms of energy generation, such as natural gas. The conventional incinerator currently under construction to serve York-Durham will also receive eight cents.

The province is in the process of reviewing its Feed-in-Tariff (FIT) program, which pays substantial premiums for renewable energy. Solar projects, for example, receive anywhere between 44.3 and 80.2 cents per kWh, with wind turbines at 13.5. Even systems recovering landfill gas receive between 10 and 11 cents per kWh.

Dufferin officials and others have been lobbying the province to include EfW facilities in the FIT program, though it’s still unclear if that will happen. Regardless, Navitus CEO George Todd says he is optimistic the rate will end up “somewhere in the middle” between 8 and 12 cents.

If no increase is achieved, tipping fees will likely need to be increased to make up the shortfall.

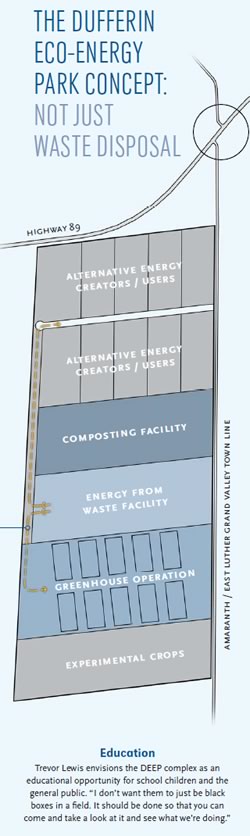

The Dufferin Eco-Energy Park Concept:

The Dufferin Eco-Energy Park Concept:

Not Just Waste Disposal

Alternative Energy Creators / Users

who: Undetermined

details: Lots of approximately 2.4 hectares each, located in the northerly portion of the site, are intended for other alternative energy producers, or businesses whose processes can benefit from the source of cheap heat produced at the nearby gasification plant.

status: Though Trevor Lewis has spoken with about five different companies that have expressed some form of interest, it’s a matter of “chicken and egg,” he says. “Once we have some sod-turning and it’s more than just talk, there will be concrete interest.” Allen Taylor, chair of the Community Development Committee, adds, “People will be lining up to bring their processes there, and we’ll be able to pick and choose what we want on the site.”

Composting

who: Joint venture between Dufferin County and York Region

details: While the EfW facility will be owned and operated by a private company, the composting facility will be publicly owned by Dufferin County and York Region, but privately designed and built. Dufferin will pay development costs leading up to the site. York, with a population of a little over a million, compared to Dufferin’s 55,000, will pay for on-site development and operate the facility.

status: Dufferin County went through a procurement process and selected a preferred vendor, who then announced it was going into receivership. York Region took over and issued a second Request for Proposals in June 2010. Due to York’s stringent non-disclosure policies, few other details are available until a report comes forward to council.

Energy Transfer Corridor

There is a tendency to think of electricity as the only form of energy produced at the site, but the gasification plant will also produce substantial volumes of waste heat. As an energy source, the problem with heat is it can’t be transported very far. A westerly corridor will deliver heat to other businesses located at the DEEP site. Conceivably, it could also be used at neighbouring properties.

Energy from Waste

who: Alter NRG Corp., Navitus Plasma Inc., Bridgepoint Group, Morrison Hershfield (consultant)

details: The privately owned and operated plasma arc gasification plant will be built on land rented from Dufferin County, with an expected life of 20 years. It will process up to 89,000 tonnes of waste per year delivered by six to eight large trucks a day, and will not be open to the public for waste drop-off.

status: Ministry of the Environment approval and financing in place by late 2012/early 2013. At that point, Dufferin should be ready to sign a Definitive Agreement, officially binding the municipality to the project.

Education

Trevor Lewis envisions the DEEP complex as an educational opportunity for school children and the general public. “I don’t want them to just be black boxes in a field. It should be done so that you can come and take a look at it and see what we’re doing.”

Road Realignment

Before DEEP can go ahead, the Ministry of Transportation has requested that the Amaranth-East Luther-Grand Valley Town Line and Melancthon 8 Line SW be realigned to form a four-way intersection. Dufferin County will pay for the work.

Hydrogen Energy Pilot Plant

who: Undetermined

details: Electrolysis, gasification and anaerobic digestion can all be used to create hydrogen, which can be stored and used to fuel electrical generators.

status: Hydrogen energy was the original catalyst for resurrecting activity at the DEEP site, when a private company expressed interest in establishing a fuelling station for hydrogen powered taxis. The concept was widely presented in early discussions about DEEP, and it was thought it might also offer a means of storing energy generated by the wind farms in north Dufferin for use during periods of peak demand. Engineering students at the University of Waterloo conducted a pre-feasibility analysis; however, the economics proved to be a challenge. Trevor Lewis reports that currently, “Hydrogen is on hiatus.”

Anaerobic Digestion

who: Undetermined

details: A process in which microorganisms break down biodegradable material in the absence of oxygen, producing a biogas that can be used as a source of renewable energy.

status: Initially, a company named Bullrush Clean Energy came forward as a partner to develop this technology, but it has not been involved for a couple of years. More recently, Canada Composting has expressed an interest. Negotiations are ongoing.

Greenhouse Operation

who: Undetermined

details: With “Eat Local” and the “Hundred-Mile Diet” movements growing across the province, DEEP is located within a hundred miles of millions of people in the Greater Toronto Area, creating a huge, potentially lucrative market. Typically, heating is a major cost in greenhouse operations, but in this case, waste heat from the EfW facility could be used, and is expected to cost about 80 per cent of usual market rates. The savings could offer a significant competitive edge. Horticulture could also benefit from the nearby source of carbon dioxide. Next to the greenhouses, an experimental crop area would be available to receive plant stock during the growing season.

status: Though conceptual discussions have taken place with a few greenhouse operators, no firm commitments have been made.

Maps by Jeff Rollings based upon DEEP documentation.

Due to rising cost projections and failure to secure another municipal partner, Dufferin County finally deep-sixed its DEEP plans a couple of years after this story appeared.

The county does not own or operate any waste facilities, has closed its municipal landfills, and contracts waste services to GFL Environmental which ships most of the county’s waste to Michigan.

You might be interested in this more recent graphic story about how GFL manages recycling of spent batteries: https://www.inthehills.ca/2018/09/where-do-old-batteries-go/

Valerie on Aug 4, 2020 at 11:05 am |

Would be interested to know what’s come of this.

Ryan on Jul 23, 2020 at 10:04 am |

Finally, some “forward-thinking”.

As a high shool woodshop teacher, former 1970’s thinker and distant observer of environmental problems and solutions I was awoken by Mr. Rollings piece “Trash Talk” .

For years as the population has grown, I have watched the various attempts to deal with the damage inflicted on the environment. And, watched as the planet corrected itself through natural cycles. I have also watched our own Caledon “dump” as it evolved from a “dump as you will” site to one that is regulated and Full.

Why, I would ask myself can you not take the trash and dump it down a magma hole and harness the resulting gases? After all, there is some 3000km of magma below us. Mind you, I could also not understand how I wasn’t having my house heated by this same magma or have my car fuelled by the fireball in the sky. To read Jeff’s article has now given me some hope. A plasma cutter in a tank. The next best thing to what I envisioned. Well done!

As for foolhardy, I hardly think so……………

Neil Barnes on Apr 1, 2012 at 5:51 pm |