On Being Vegetarian

When Julie Suzanne Pollock decided to stop eating meat, her friends and family were not amused.

I stopped eating animals 24 years ago. My weekly cruise up the tidy meat aisle could not be reconciled with what I knew, as a country girl, about blood and death. I was unsettled by the sight of cattle trucks on the winter highways, the blind faces of windowless chicken barns, and my awareness of the intelligence of pigs. On the other hand, I knew nothing about being vegetarian.

As it turned out, neither did my doctor. She had only one idea, but it was a good one. “Start by reading Diet for a Small Planet,” a 1970s best-seller by Frances Moore Lappé about world hunger. I had hardly opened this sensible little book to begin my self-education when arguments erupted all around me.

Friend, family, foe, they all wanted to know the same thing. “Why won’t you eat meat?” Those were the days when distinctive eating habits were viewed with suspicion. Some friends wanted to argue about ethics. Some lectured about hunter-gatherer culture. Others proselytized for the health of the beef industry.

The acidic tone of some caught me off guard. “You wouldn’t be vegetarian if your plane crashed on the tundra and all you had was a gun.” True perhaps, but not a test I was likely to endure. “Your shoes are probably all leather.” Not true, but always delivered with squinty-eyed certitude. One standout accusation took us into quasi-religious territory. “If you still eat eggs, you must believe in abortion.”

People would invite me for dinner and toss me a dry veggie burger while the other guests dug into beautifully prepared salmon. One Christmas week, my mother-in-law served me day-old greens flung on a plate. I could appreciate I had entered a minority group and had to put up with some kitchen incompetence. Nevertheless, it rankled, because day after day I was willing to cook meat, fowl and fish for my loved ones. Was it so hard to dig up one vegetarian recipe?

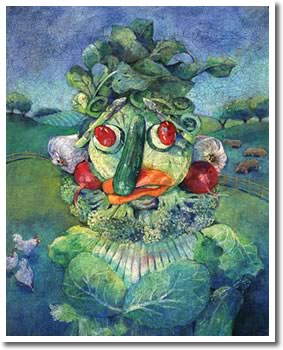

When Julie Suzanne Pollock gave up meat, she discovered the personal and the political are sometimes inseparable. Illustration by Shelagh Armstrong.

Why wouldn’t I eat meat? I was grappling with the question myself and was fraught with defensive insecurity. I cringed at allusions to ethical failings in other areas of my life. Back then I smoked, and a few people made connections between the tobacco industry and animal farming. They challenged me on arcane points of ecology, economy and agriculture. It took me some time to decipher the reason for their angry undertones. I realized skipping the meat course is political – for some, being vegetarian equalled left-wing radicalism.

Those arguments did me great service. They forced me to examine my own hypocrisies. I perceived what I had stopped putting in my mouth was still scattered around my person – leather books and handbags, ivory jewellery, feather pillows. Animals were still dying for me, I just wasn’t eating them.

So I changed my buying habits. Then it got complicated. Weren’t dairy cows pregnant with meat-destined calves? And what about laying hens? Honeybees? I thought I should be vegan. I knew my family and friends would be even more impatient with me. So I compromised by only swearing off dairy. “You’re getting weirder,” said my mother. No one asked me to dinner anymore.

Vague in my evolving philosophies, I probably came off as flaky. I was too emotional to be articulate, and I was pissed off at having to defend my choices. I didn’t know much about public policy or agri-business. I’d always been a person who lived by her heart. It seemed to me anyone could see there was a problem with food in the world. There was famine in the midst of abundance. There were hordes of species vying for food every day, and people were snapping up most of it without a thought for the rest of the beasts.

Then I spent a month in Tanzania. I couldn’t get “non-dairy vegetarian” across to the lean brown locals in the restaurants of Dar es Salaam. No nyama, ok. There are plenty of reasons why you might avoid meat. But anything more finicky was simply off the table. Why wouldn’t you eat the rice with creamed curry squash and peppers? Why indeed? I fell off the milk wagon.

And I didn’t feel that badly as I stirred rich cream into my coffee for the first time in five years. Something relaxed in me. Layers of First-World guilt fell away like a snake’s skin and pleasure returned to my table. Where there was angst, there came perspective.

I had been picking holes in the tablecloth of abundance. Under the tropical sun, I savoured native cashews in neat foil bags from the local roastery. I sat on the beach watching fishermen tossing nets for the evening’s catch. I sampled fresh fruit from street-side tables tended by hard-working farm families. I felt a connection to the harvest that I had lost.

I’m still skipping the meat course and I haven’t changed my mind about industrial-scale farming. But I have come to see that choices are subject to circumstances. And I stand behind the harvest of my choice with equanimity.