The Homecoming

To a 13-year-old Orangeville boy in September 1945, news that the father he hadn’t seen in four years was on his way home from the battlefields of Europe was cause for high excitement.

Jim Welsh’s father, Little Jimmy Welsh, broke his wife’s heart when he enlisted, but he cut a dashing figure in uniform and made it home safely after serving with the Princess Louise’s Hussars, a New Brunswick tank regiment, and later as batman for Major Clifford McEwen.

Seven hundred forty-one men and women from Orangeville enlisted to serve in the Canadian Armed Forces during World War II, and the 708 who returned didn’t arrive all at once. They came in dribs and drabs. Ernie Hodgson sneaked home in the middle of the night. Jim Welsh, a 13-year-old who was eagerly awaiting his father’s return, remembers Ernie was so tired that he didn’t want a big hurrah. Many of the guys, including Jim’s dad, Little Jimmy Welsh, felt the same way.

But the homecomings were big news in town, recalls Jim, now 81. Orangeville’s population was barely 2,700 at the time, and when someone was expected home from overseas, the word “spread like hell,” he says. “‘Billy Whitfield is coming home! Ossie Whitfield’s on his way back!’ We knew them all. Most of them were about five years older than me. We looked up to those guys. They were the heroes of the town.”

Little Jimmy Welsh, all five-feet-six-inches of him, had been a rivet thrower in the shipyards of Newcastle, England, and had come to Canada to continue plying his trade. On landing in Toronto he was shocked to find boats, not ships, on the waterfront.

In 1928-29, Little Jimmy ended up working on the crew paving Hurontario Street up Caledon Mountain. By the time he enlisted on March 31, 1941, he was a 33-year-old married father of three and supporting his family by running a spinning machine at Dod’s Knitting Mill, Orangeville’s major employer. Today, the mill has been transformed into the handsome brick apartment building at the corner of Mill and Church streets.

“Dad didn’t have to join,” says Jim, who was known as Junior in those days. But four Englishmen, buddies at the mill, including Little Jimmy and Alf Sillet, who later owned the Texaco station on First Street, had been talking about the war. It was Alf who put it pointedly: “The homeland’s in a lot of trouble over there, boys.”

So that day Junior arrived home from school at lunchtime to find his mother, Catherine, fretting. “I can’t understand where your father is,” she told her son. A person could set a watch by the routine of the factory workers. His mother soon sent Junior running to the mill to find his father, but Old Joe Dod hadn’t seen Little Jimmy all morning. This news further upset Catherine, who insisted that Junior come straight home after school.

“When I came through the door, boy, Dad was catching hell from my mother,” says Jim. “She was crying and yelling. I had never seen them like that.” Little Jimmy had signed up for the army, and five months later he headed to England with the Princess Louise’s Hussars, a New Brunswick tank regiment. He ended up as the batman for Major Clifford McEwen, who was courting an army nurse from Alliston. “The major took to my dad,” says Jim. “[Dad] was a likeable man and he would work very hard for you.”

A few days before Jim’s father was due home, Armour McMillan, who ran McMillan’s garage and taxi service on Broadway (located roughly across the street from As We Grow, which is at 113 today) paid a visit to the Welsh home at 11 First Avenue. Junior and his two sisters, six-year-old Maureen and eight-year-old Sheila, sat in the dining room with their mother and the guest. Little Jimmy would arrive by train in Toronto, and McMillan knew the Welshes didn’t like to drive. How was Little Jimmy planning to get home from Toronto? McMillan asked, and offered to chauffeur the family to the city to meet him.

“To answer the question,” says Jim, “I remember my mum, a frugal lady, blurting out something about not being able to afford the fare and Mr. McMillan saying, ‘Oh no, for free.’”

Jim remembers enthusiastically decorating the house, inside and out, with streamers and signs saying “Welcome Home, Dad.” “We put them up a wee bit early,” he says, and the family had to replace them at least once because of the weather, but that didn’t matter. The whole town knew Little Jimmy Welsh was coming home.

As a boy, Junior had thought of the war as a great adventure and he followed events on the radio, in the newspapers and through the newsreels that preceded the featured film at the Uptown Theatre. “I knew my dad was over there fighting. But who in the hell is going to get killed? Nobody is going to get killed … but they were, left, right and centre.”

When a local boy was killed, everyone felt it, he says. “All those guys on the cenotaph, I knew every damn one of them.”

“My Aunt Monica, my mother’s sister who lived in Toronto, had said to my mother, ‘When you come down to pick up Jimmy, you come here before you go home, Cath. I’ve got to put my arms around Jimmy.’” Monica’s husband Cristy Jenkinson had been killed in Belgium on September 10, 1944.

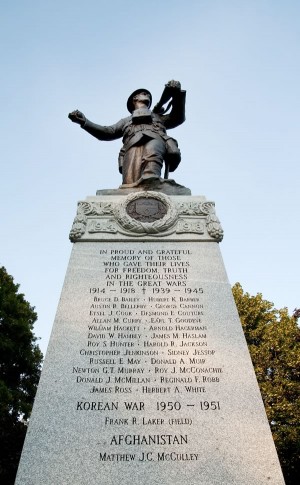

The cenotaph in Alexandra Park in Orangeville was unveiled in a ceremony on November 12, 1923. The names engraved on the monument now include all those from Dufferin County who never returned from the great wars of the last century. The list includes Donald McMillan, son of the Welsh family’s friend Armour McMillan. The most recent name to be added is that of Matthew McCully who died in 2007 in Afghanistan. Remembrance celebrations continue to take place at the cenotaph each November 11. Photo by Rosemary Hasner / Black Dog Creative Arts.

On the big day McMillan didn’t blink at the prospect of making a side trip to Monica’s home. “I’m yours for the day,” he said, no doubt thinking of his own son Donald, who wasn’t among those coming home. Donald was 23 when he was killed on February 1, 1945. As a navigator on heavy bombers, he had completed more than two dozen missions over Europe before his crippled aircraft crashed. He left his young wife Beatrice and baby daughter Patricia, whom he had never met.

The returning troops arrived at Toronto’s Union Station by train from Halifax, where they had disembarked from the steamships that had ferried them across the Atlantic. The plan was to transport them by truck to the CNE grounds, where they would parade into the football stadium before being discharged. Their families were seated alphabetically in the stands. The Welshes were lucky to be seated with the rest of the Ws under the overhang, which provided some protection from the cold wind off Lake Ontario. But the wait seemed endless, despite the authoritative updates provided by the voice on the giant loudspeakers.

“We could hear the band playing in the distance as they marched into the stadium,” Jim recalls. “My mother is there trying to keep the three of us in tow. ‘Don’t you get away on me! Don’t you get away on me!’ I am all anxious to see my father. In marched the first bunch. They all paraded down and got formed up, and by God, if I didn’t spot my dad.” The men were ordered to hold their positions and look toward the section lettered by their last name.

According to Jim, that didn’t last long. “Well, we poured out of the stands. When I think about it, I don’t know how I didn’t kill myself. I guess I was young and agile. I remember the man on the speaker kept saying, ‘Please, please, hold your positions. Please, ladies and gentlemen, let the men get onto the football field.’

“I was standing on the field in front of my father. I was so proud. Then Mum and the two girls got there. Maureen is hanging onto Mum’s dress and looking at me. ‘Who’s that man?’ she asks. ‘That’s your dad.’”

Meanwhile, Jim’s grandmother, cousins, aunts and uncles had congregated at Monica’s house. “My aunt had a terrible time. She wouldn’t let go of Dad. He didn’t know what to say to her.”

McMillan then drove the family to Orangeville in the familiar pale blue, four-door Plymouth sedan that didn’t need a sign to be hailed. Shortly after the family arrived at the house on First Avenue, the phone began to ring and people started knocking on the door. “Hi, Jimmy. Good to have you home.” But all Little Jimmy could think about was his youngest, Maureen.

Barely two and a half years old when her father had left for war, Maureen regarded him as a stranger. “I’ve got to do something about the baby,” a heartbroken Little Jimmy kept saying. So the next day, and every day for the next two weeks, he walked Maureen to Broadway and bought her an ice cream at Merv Henry’s confectionery.

“He did whatever the hell it took, and it took quite a while,” says Jim. But the strategy worked. Just ask Jim’s sister, Maureen Jessop. She thinks the world of her dad.

More Info

Note: Jim Welsh graduated from Orangeville High School in 1950 and remains a member of the informal Old Boys’ Club. See “Friends of Their Youth”.

I am the daughter of Major Clifford McEwen mentioned in this article. I certainly had heard the name “Jimmy Welsh” when I was growing up and remember going with my parents to visit him in Orangeville when I was a child. I’m sure he was a wonderful man as was my Dad. We should be thankful every day for the sacrifices they and others made for our freedom. By the way, the nurse Dad was courting was my mother. A relative in Ontario spotted this and sent me a copy.

Mary Jane McEwen on Oct 1, 2013 at 1:23 pm |