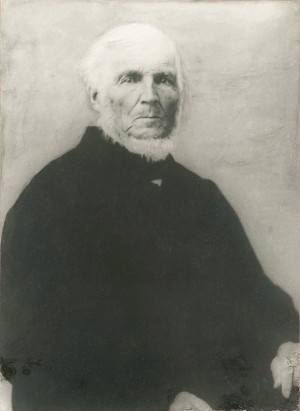

Seneca Ketchum

Seneca was nearly 60 when he came to Mono, an age when many people look forward to ease and comfort.

Some of his contemporaries admired his generosity, devotion and commitment. Others called him a stubborn zealot, eccentric and “not very sane.” But all of them agreed on one point: Seneca Ketchum was impossible to ignore.

Around 1830, when Seneca Ketchum settled in the Purple Hill area of Mono Township, the capital of Upper Canada was still called York, settlements such as Bolton and Erin were tiny blips on the map, and these hills had yet to meet Orangeville’s deemed founder, Orange Lawrence.

But to Seneca, the gradual spread of civilization into the wilderness of newly surveyed Mono Township was an opportunity to pursue his life’s passion: spreading the word of God via the Church of England. For 20 years he did just that, in Mono and beyond, with an intense single-mindedness that moved almost everything in his path.

Worthy of a Dickens Novel

Seneca was nearly 60 when he came to Mono, an age when many people look forward to ease and comfort. And that choice was open to him – by 1830 he’d become well-to-do on his lands in present-day North Toronto. But the plot of Seneca’s life, even its very beginning, was anything but ordinary.

He was born in 1772 near Albany, N.Y., just in time for the American Revolution, which, because the Ketchums were Loyalists, made for an uneasy and often dangerous childhood. In 1788 his much-loved mother died after the birth of her 11th child (she was just 36), and like a character in a Dickens novel, he was literally tossed out into the world. Ten Ketchum children were settled with neighbours, but Seneca, at 16, was told to fend for himself.

Another Dickensian blow was delivered when he reunited some years later with his younger brother Jesse (see sidebar), freely taking Jesse into his comfortable home where the housekeeper was a radiant young widow whom Seneca hoped to marry. The housekeeper married Jesse.

But perhaps the greatest emotional pain of all for Seneca was an unfulfilled desire he carried throughout his life. From early childhood on, he felt a powerful call to the ministry and had committed his life toward becoming ordained. However, circumstances conspired against him and it never happened. Still, it was this dream of ordination that brought him to Canada.

For Seneca, only the Church of England mattered, and in post-revolutionary America that made him an outlier. Thus in 1792, with his hope of achieving holy orders still very much alive, he set out for a country where the denomination meant something. At age 20 he landed in Cataraqui (Kingston) where his passion for expanding the Church of England took its first step.

Upper Canada’s Busiest Churchman?

Over the next 50 years Seneca Ketchum became what one historian called “an Anglican whirlwind.” The year he arrived in Kingston, he helped establish that community’s first Anglican church. Within months he had moved to Newark (Niagara-on-the-Lake) and helped build St. Mark’s there. When Governor Simcoe moved the seat of Upper Canada to York, Seneca moved too, and in 1797 became a builder, charter member – and voice to be reckoned with – of York’s first Anglican church (eventually St. James’ Cathedral).

On Sunday mornings, from his home near present-day Yonge Street and Highway 401, Seneca would walk two hours to St. James’ for morning services. Then in the evening he would hold a lay service in his home – until 1816 when he cofounded St. John’s Anglican in York Mills. With this neighbourhood church in place, he then moved these home services to Thornhill and Markham. All this before he moved to Mono where his activity ramped up even further.

Preacher, Builder, Benefactor, Irritant

Seneca came to Mono with a theoretical step up in the Anglican hierarchy. He was licensed as a lay missionary by Archdeacon (later Bishop) John Strachan. It was an unpaid, quasi-official position that gave Seneca some status, but it is easy to believe Strachan saw it as a way to entice Seneca to leave York where they regularly locked horns. In any case, the new lay missionary was eager for challenge and his arrival in Mono was marked by a flurry of activity that began before the ox carts were unloaded.

Like all first-in pioneers, he built a family home and then helped build more homes on his several tracts of land for the families he’d persuaded to come to Mono with him. Over subsequent years he built bridges and roads and was regularly celebrated for providing food to the township’s pioneer families.

But all this effort was secondary to his lay missionary work. He spread the word, freely handing out Bibles and the Book of Common Prayer. He taught catechism (and literacy), and held services everywhere at every opportunity. These hills were still the domain of the saddlebag preachers in the 1830s, and because Seneca’s home became a regular way station for them, his role continued to expand.

In 1837 Seneca built St. Mark’s, arguably his most enduring legacy because it became the foundation for today’s St. Mark’s Anglican parish in Orangeville. This first version was a log church on Seneca’s land on Mono’s 1st Line East. It instantly became a focal point of religious activity in the township and beyond. And, possibly because it was a project by Seneca, it quickly attracted some controversy too.

Just six concessions to the east at Mono Mills was St. John’s, also an Anglican parish. Neither church had a resident ordained minister, both being served by an overworked itinerant pastor (called “travelling missionary”) who had still other churches in his charge. There being no rectory, the two Mono churches competed to house this pastor, and it seems St. Mark’s, as a consequence of Seneca’s generous hospitality, was a frequent winner. This not only stirred the ire of the parishioners at St. John’s, but even led Bishop Strachan to warn one itinerant pastor there was “much to fear from Seneca’s excited state of mind.”

Sadly, Seneca died before St. Mark’s ever did get a resident pastor, but throughout the 13 years after building “his” church, he continued to pursue his passion at full throttle, preaching, teaching, building – and giving. In 1845 he gave the (Anglican) Church Society of Toronto 300 acres “for the benefit of the missionary doing duty in Mono Township.” He built a rectory at Melville. Although records are fuzzy, he is said to have built at least six more churches, likely family chapels, in Mono.

Although Seneca never escaped his reputation as an eccentric (perhaps deserved to some extent – in 1847, for example, he set aside land in Caledon Township for a Sailors’ Home), there can be no doubt about his significant contribution to the development and growth of Upper Canada. In the early history of these hills especially, there are few pioneers to match him for energy, achievement and profile.

More Info

Sorting Out the Ketchums

Seneca’s brother Jesse (1782–1867), younger by ten years, is perhaps the best known of this active and influential family, owing to his involvement in the Upper Canada Rebellion of 1837, his successful commercial and real estate enterprises in Toronto and Buffalo, N.Y., and his support for universal education. (A Toronto school is named for him.)

He was a philanthropist and, like Seneca, a strong believer in temperance (their father, also named Jesse, was a notorious drinker). Unlike Seneca, this Ketchum was a Presbyterian. (Perhaps not coincidentally the brothers’ housekeeper, Ann Love, whom Jesse married in 1804, was a fervent Presbyterian.)

A third Jesse (1820–1874), the son of Jesse and Ann Love, is well known in Orangeville. This Jesse is credited with positive developments in the town, such as the wide design of Broadway, its main street, and the numbered grid pattern of streets to the north. He also donated the land for present-day St. Mark’s in 1854.

Orangeville’s Jesse is buried at Forest Lawn Cemetery on the edge of town. His father lies in Buffalo, N.Y. Seneca is buried at St. John’s, York Mills. He died there while in Toronto to petition Bishop Strachan for a full-time pastor for his beloved St. Mark’s.

to Kelly Hannahson Horwood in the first question: My husband is a descendant of Hannah Ketchum, who was forced, by her two brothers in Canada, to change her last name so that her son (of an unknown “Mali Man”) would not bring shame to the family. There seems to be much legend around the true story of Hannah’s life with her son. Hannahson, the new name, came from “Hannah’s son”. The name of George’s father has been lost. I am, however, still going to try to find it.

Ellyn Peirson

Ellyn Peirson from Guelph, Ontario on Aug 22, 2021 at 6:40 pm |

In your research on Seneca do you know what happened to Hannah?

Kelly Hannahson Horwood from Georgetown On on Nov 26, 2017 at 4:25 pm |

In my research on the Ketchum family pertinent to Orangeville and area, I did not encounter a ‘Hannah’ at least not as a spouse of Seneca, Jesse or Jesse Jr. You may be referring to one of the children of Jesse or Jesse Jr. My research did not take that direction.

There is a Hannah Ketchum who lived in New York state who would have been a contemporary of Seneca’s parents (lived near Albany NY) but I am unaware of any specifics.

If the Hannah you refer to is/was Canadian I suggest you try the Metro reference Library in Toronto where the Ketchum name was once prominent. If she is a New York Ketchum you may want to investigate via the State University of New York in Buffalo where Jesse Senior was a major benefactor. The archives there will surely have information.

Ken Weber from Caledon on Nov 28, 2017 at 6:36 am |

Ken, was just reading your latest article about Seneca Ketchum. I live at 2525 Highpoint Sideroad in Melville, Caledon, On. and I noticed you mentioned he built a rectory in Melville. I live on the property where the church stood on the south east corner of Highpoint and Willoughby. I have been unable to find a picture of this church in my research, but did find the article in the Sun Newspaper about it being destroyed in a storm. Would you be able to offer any help in where I might be able to find a picture. I even visited the Brampton Museum and the Dufferin Museum without any luck. Any info. would be appreciated. I also think a sign should be posted wherever these old churches once stood proud.

Thanking you in advance,

Karen Sherrard

Karen Sherrard on Mar 25, 2015 at 4:16 pm |

To Karen Sherrard: I did not encounter contemporary photographs of any kind during my research on Seneca Ketchum. You might try the archives of the Anglican Archdiocese of Niagara or of Toronto as Melville bordered both administrations. To pursue the idea of a heritage sign, a request to Heritage Caledon or the Caledon Heritage Foundation would be a good start.

Best wishes, Ken W.

Ken Weber on Mar 31, 2015 at 11:25 am |