The Borders of Paradise

In the face of urban sprawl, budget cuts, and provincial service transfers, local municipalities struggle to define and preserve rural values.

“Well folks, today Toronto is a city of two million. In twenty years, it will be four million. Now where do you think those people are going to live?”

That was the question posed to a recent meeting of rural politicians by Alan Tonks, a former Metro Toronto councillor who is expected to be appointed chair of the new Greater Toronto Services Board when it comes into effect on January 1, 1999.

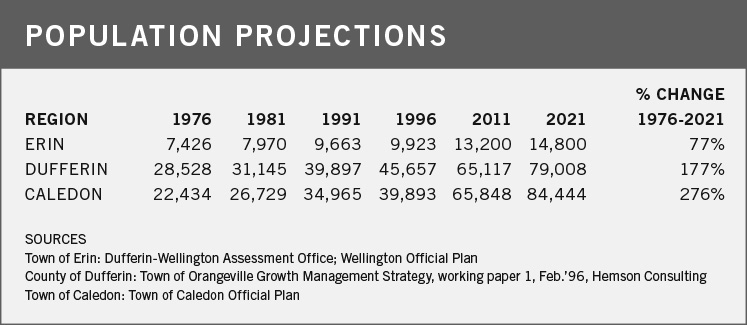

If some provincial and municipal politicians have their way, the answer to Alan Tonks’ question may be that tens of thousands of those people will live in the new City of Peel (an amalgamation of Brampton, Mississauga and Caledon) or the City of Dufferin (Orangeville, Shelburne and the county’s six townships). Or some of them might relocate to the mega-county of Headwaters (Erin, Caledon and Dufferin).

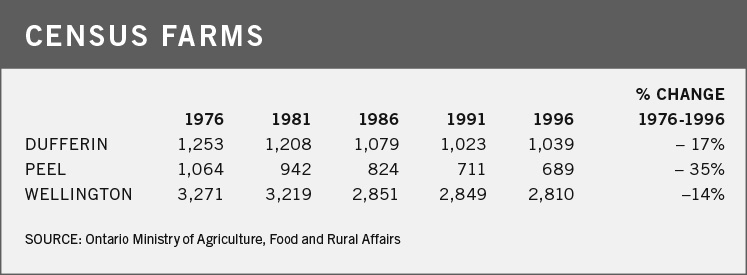

As he drove up Highway 10 on a visit to Caledon last March, the same Alan Tonks reportedly exclaimed, “Look at all that vacant land!” The comment doesn’t surprise Caledon farmer David Armstrong. City planners think of land use in only one way, he says. “To them agricultural land is vacant land waiting to be developed.” Caledon councillor Ian Sinclair concurs. Urbanization, he says, could mean that “there won’t be any farming in Caledon in fifty years … We will be Bramalea with hills.”

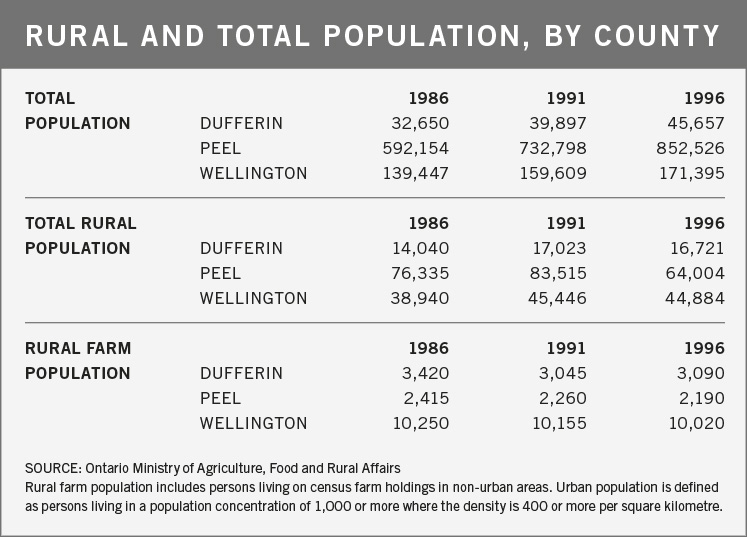

It is predicted that 90 per cent of the population growth in the Toronto region will be in surrounding communities of Halton, Durham, York and Peel. That growth, with its attendant residential and industrial development, puts tremendous pressure on all the municipalities in our rural hills. And though Bramalea-style development may be everyone’s worst-case scenario (the Brampton suburb has become the local code word for crowded, anonymous housing in a coreless, bedroom community), it’s hard not to be seduced by the tax revenues that development can generate, or the services those revenues can buy.

The provincial government’s decision to turn over its role in approving official plan amendments to regional councils may further tempt hungry municipalities to pursue development. (Where the province once reserved the right to approve or reject amendments, its role is now on a par with any other private citizen who appeals to the Ontario Municipal Board.) The Niagara Escarpment Commission, the other major check on development through much of these hills, lost more than one-third of its budget three years ago. With these changes, municipal governments are having to add increased planning responsibilities to the long list of new services they’ve been forced to pick up. Yet many municipalities, including Dufferin County, do not even have a planning department.

Development pressures, along with the province’s transfer of services to municipal budgets and its gospel that amalgamation saves money, have pushed most local municipalities into a concerted re-examination of their traditional roles and structures.

Last year, the new Town of Erin emerged when the Village of Erin and the Township of Erin were rolled into one. Dufferin County is embroiled in a heated debate about its restructuring options. And the Town of Caledon is trying to figure out how to protect its rural values if it is gobbled up in a new, single-tier City of Peel.

For the Town of Caledon, there’s nothing new about amalgamation. In 1974, the ten townships that made up the County of Peel were amalgamated into the Regional Municipality of Peel. The regional government (upper tier) comprises representatives from the elected councillors of the three (lower tier) municipalities: the mostly rural Town of Caledon (comprising the former townships of Albion, Caledon and part of Chinguacousy) has five votes on regional council; the City of Brampton has six votes; and the City of Mississauga has ten votes. The amalgamation process was more than a little contentious. Even the choice of name – Caledon, Albion or Cardwell – was not unanimous and many angry residents and politicians thought no good would come from the abolition of the small townships units.

The new town’s second mayor, John Clarkson, pledged to make Caledon the Hollywood of Toronto. During the next twenty-five years, although hardly on a par with California’s enclave for the rich and famous, Caledon has indeed come to include the wealthiest community in the Greater Toronto Area. Real estate values have skyrocketed and, although property taxes have gone up with them, the town enjoys a level of services superior to its neighbours to the north and west. Excellent policing, waste management, a sophisticated planning department, and financial stability are some of the benefits attributed to Caledon’s association with Peel.

Caledon councillor Richard Whitehead, an alumnus of the town’s first counciI and an unabashed supporter of regional government, notes that Caledon’ s association with Peel means it can borrow money at a better rate than the provincial government can.

Since 1974, the town’s population has more than doubled from about 19,000 to 40,000. The town’s carefully planned strategy of limiting farm severances and avoiding strip development in favour of block estate development, as well as generally restricting residential subdivisions and industrial development to the existing higher density areas, meant that the visual aesthetic of the Town’s scenic countryside was largely preserved. As septic systems began to tax local assimilative capacity some Caledon communities were linked to sewage treatment facilities in Mississauga. And a shortage of groundwater may soon force residents to pipe their drinking water from Lake Ontario. Today, about 40 per cent of Caledon’s residences are hooked up to municipal sewers and about 5 per cent get their drinking water from the South Peel System. These urban-style sewage and water links, along with new communal septic system technology, have removed one more barrier to development. When such municipal services become available, higher resdential densities are possible and growth-averse politicians are less able to muster arguments against development.

On the northern border of Caledon, Mono Township reeve John Creelman says Mono is not tempted to follow that town’s lead. “Quality of life is not necessarily measured by the size of your sewage system,” he says. “We don’t want the experience in Mono where all of a sudden our aquifers are polluted and we’re dependent on piped water and sewage. We would like to control our growth so that those kinds of costly scenarios don’t become inevitable.” The reeve says Mono will approve no new plans of subdivision. And he notes that the township has not had a significant tax increase in nearly a decade. He suggests that most Mono residents are happy to have fewer so-called enhanced services in order to preserve certain rural values.

But in Mono, as elsewhere in these hills, the definition of “rural values” may be in transition. Over the past two decades the number of “newcomers” to the hills has grown to exceed the number of “old-timers” (those who were born, or at least raised, here). And the phenomenon is not exclusive to this region. Joel Kotkin of the Pacific Research Institute describes the migration of the baby-boom generation to rural areas as the Valhalla Syndrome – people “yearning for a heavenly retreat”. The migration puts pressure on rural communities and natural resources because newcomers are often unfamiliar with existing rural values and generally expect their heavenly retreat to offer all the services they had in the city. Author David Foot pursued the theory at length in his book, Boom, Bust & Echo, noting that measures to protect farmland, forests and aquifers must be in place before newcomers arrive, “because once they are installed, it will be much harder to impose new regulations.” (See sidebar.)

In its new official plan, setting a course for the next twenty-three years, Caledon proposes to balance growth with the preservation of its greenland and farmland. Its statement of strategic direction reads in part: “The location of the Town, on the edge of a growing urban area and the existence of natural heritage resources, one of which is of global significance, requires that the Town play the role of steward for these natural resources and the lifestyle of existing residents. This responsibility has to be balanced with the Town’s responsibility to future residents and as part of the Greater Toronto Region.” To protect its resources, the town has adopted an ecosystem-based planning and management approach. It places the preservation, protection and enhancement of Caledon’s natural physical and biological features on par with fiscal responsibilities and the health and wellness of residents.

But Caledon’s ability to control its own destiny may be severely undermined by its membership in the Greater Toronto Area. Rural neighbours sat, often smugly, on the sidelines of the bitter battle over the creation of the Toronto mega-city. What many didn’t fully realize was that the amalgamation of Toronto was just the first step in a grand plan. Now there is talk of further amalgamation within the 905 regions (with municipalities in Peel, Halton and York to be absorbed into single-tier cities). The plan calls for the services within the 905 and 416 areas to be controlled by the new Greater Toronto Services Board (GTSB).

A board that co-ordinates services across municipal borders might sound like a good thing. The difficulty for Caledon and other rural municipalities in the GTA (King and Halton) is that the GTSB is dominated by its urban members (Toronto, Brampton and Mississauga, among others). Although rural municipalities represent 70 per cent of the GTA’s area, they will collectively have only 10 per cent of the vote on the GTSB, compared to 50 per cent for the City of Toronto. In fact, Caledon will have less than 1 per cent of the total vote on a board which has the power to co-ordinate, manage and tax all municipalities in the GTA for what is still a poorly defined set of services and infrastructure development.

“Do you think [Toronto mayor] Mel Lastman should have the right to set tax rates and create debt for Caledon and other municipalities outside Toronto?” Alf Richmond, chair of the Town’s governance committee, recently asked council. The committee, appointed by Caledon to examine the issue, has declared that “the dominance of Toronto within the GTSB is unacceptable.” In creating the GTSB, premier Mike Harris seems to have ignored his own 1992 Rural Report in which he wrote, “It’s not a good thing when the interests of small communities are left in the hands of big-city politicians who don’t understand rural life.”

Caledon mayor Carol Seglins, however, cautiously continues to favour Caledon’s involvement in the GTA. “Part of what makes the GTA great is that it has a green fringe,” she says. She believes that the rural municipalities of Caledon, King and Halton should form a rural partnership and seek the right to steward their own natural resources. “We must gain control of our aggregates so Toronto and Mississauga developers cannot extract them at will. We need to protect ourselves from their ‘post-collection waste’. We need to determine how to handle our natural resources, recreation amenities, headwaters and agriculture so we can be self-sufficient at a reasonable cost.” Without that control over its own resources, the mayor acknowledges, the only solution “may be to opt out [of the GTA].”

One county north, in Dufferin, the stage is smaller, but the drama is similar. Dufferin County comprises the towns of Orangeville (pop. 21,400) and Shelburne (3,500) and six townships of which Mono is the largest (6,000). On the sixteen-member county council (appointed from the elected lower-tier councils), weighted votes give the two towns 50 per cent of the vote, so that any motion requires only one vote from any of the rural townships to carry.

Urban-rural tensions in Dufferin escalated recently with a plan put forward by the county’s general government services committee to initiate a restructuring study. The principles outlined in the original terms of reference for the study called for less government, including fewer municipalities and fewer elected representatives, and fewer layers of government. In a county with only two tiers of government, “fewer layers” could mean only one thing: a single-tier county government.

That principle sent most of the county’s township councils into a frenzy of opposition. Earlier development plans proposed by Orangeville had called for a move to independent city status, with a population target of 55,000 by 2021. Such growth could only be accommodated by adding territory. Orangeville’s plans to annex land from Caledon and the surrounding townships in Dufferin met strenuous opposition from those municipalities. Among other concerns, they were not satisfied with the viability of the town’s sewage disposal plans which projected a huge increase in the effluent dumped in the Credit River.

Although Orangeville’s annexation plans were apparently dropped with the election last fall of a new mayor, Rob Adams, some suspect that the restructuring proposal was simply annexation in another guise. “By eliminating township borders, Orangeville would neatly solve its annexation problems,” says Mono reeve John Creelman. Because the carrying capacity of the Credit River is limited, he says, in order to grow, Orangeville needs access to a second river system. He suggests that the creation of one big City of Dufferin would provide Orangeville with access to both the Grand and the Nottawasaga rivers by eliminating the impediment of lower-tier official plans.

The reeve led a successful bid to have the restructuring study changed to a “review of services and governance”, with the pre-determining principle of “fewer layers of government” removed. However, opponents in the townships were unable to wrest control of the process from the hands of the government services committee, which has the same urban majority as county council. Although the title and terms of reference for the study were changed, many township councillors feel Orangeville has simply taken its original agenda underground.

Their fears are fed by the fact that Orangeville mayor Rob Adams’ 1992 Masters’ thesis concluded that the best route for Orangeville was to annex land and separate. Rob Adams says his thesis paper is “irrelevant to the current situation”, but others are not convinced. As a result of their concerns, the townships have set up a parallel ad hoc committee to study governance issues. On the ad hoc committee, each municipality has equal representation.

Rob Adams is frustrated by rural suspicions of his motives. ”As soon as I go to county council I’m seen with a progrowth Orangeville hat, yet people in Orangeville would put me into the antigrowth camp,” he says. “I fought against WalMart and I opposed increasing development densities. I was elected because people in Orangeville have recognized that growth has gone too far, too fast.”

The mayor claims that he doesn’t want big regional government. That style of governance, he says, came about in a period of big money when the idea was “to create large economic engines of government.” He explains, “My personal view is that we need a more simplified governance structure based on a predominantly rural makeup that reflects the community and the natural environment.” He would like to see a system of publically appointed boards advising part-time elected representatives who live in the communities they represent. And he wants a better balance between rural and urban interests that recognizes their interdependence. He says a rural voice will help urban voters “to see the bigger picture, the watershed, for example, and the effects of decisions on our surrounding countryside.”

At thirty-five years of age, he remembers well his university training. “We learned that in 1881 towns were built to be separated by a day’s journey. Now technology has changed all that. I thought the idea of changing arbitrary political borders to follow watersheds would take off. Natural landforms and boundaries influence what a community should be … We must be more sensitive to our natural environment.”

The closest the mayor can come to a model for his vision is the Headwaters Country Tourism Association, which was organized along natural boundaries.

It’s a model that Caledon councillor Ian Sinclair has developed considerably further. He is busy marketing the concept of a Headwaters mega-county, comprising Erin, Dufferin and Caledon. The proposed “countryside” county contains the sources of eleven rivers, and sections of the Niagara Escarpment and the Oak Ridges Moraine. Sinclair notes that “Shaping Growth in the GTA”, a consultant’s vision of development in the region, calls for the countryside around the city to be established as a permanent feature rather than a landscape awaiting development. But the countryside will be much easier to preserve if it is politically distinct from the city, Sinclair says. He is in favour of Caledon opting out of the GTA. He argues that the establishment of countryside municipal jurisdictions surrounding the GTA with a mandate of low growth and natural resource stewardship, could be an effective mechanism for containing sprawl.

Ian Sinclair’s proposed mega-county would have a single-tier government, limited to no more than eighteen council members for the region’s 100,000 constituents. The large population base is needed for financial security, he says. He estimates that with one level of government and some provincial subsidies to cover commuter and weekender road use, such an amalgamation could be tax neutral.

A rural alliance to support countryside values appeals to Mono reeve John Creelman, but he remains adamantly opposed to the notion of single-tier super-governments. The financial savings are largely illusory, he says. If they exist at all they are made at the expense of the accountability of the elected politicians to their electors. “There’s usually fewer elected officials, they’re usually full-time politicians, with large full-time salaries, and that tends to attract a different kind of politician.”

The reeve argues that local planning also suffers in a single-tier scenario. Regional plans tend to be much more general, more vague, and “frankly much more open to interpretation of the bureaucrats who wrote them,” he argues. “I should point out that Peel has taken nearly twenty years to process its official plan – there’s an indication of regional government in action.”

Finally, he says, “When you put all the communities together, you start a slow process of homogeneity … The purpose of local government is to provide a voice at the grassroots level. As soon as you start reducing the number of elected representatives and increasing the geographic area they represent, the more you dilute the voices of individual ratepayers.”

The reeve goes so far as to suggest that it is not township governments that are redundant, but county government. The townships, he says, are “small, viable units of local government” that could purchase certain social and recreational services from each other, and set up inter-municipal volunteer boards for shared services. “I can’t name one service that the county provides that couldn’t be provided by a joint board or by a single municipality which sells the service to its neighbours.”

David Tilson, MPP for Dufferin-Peel, says the role of municipal government is indeed “to provide grassroots services the provincial and federal government cannot.” But, he adds, “It may be that municipal governments are doing more than they can afford to do.” He suggests money could be saved if municipalities replaced or supplemented paid employees with volunteers: ”As more and more people are retiring, there are all sorts of things they would do for free.” And he offers an admonishment to municipal governments: “You shouldn’t just be holding the line on taxes, you should be reducing taxes.”

It’s a tall order for municipalities who suddenly find themselves with former provincial highways to maintain, a whole new set of social services transfered to their budgets, and no guarantee that the provincial government’s commitment to revenue neutrality will last beyond its current term. Opening the doors to industrial and residential development and reducing the number of elected officials are tantalizing options for generating municipal revenue.

But for John Creelman, there is no proof that amalgamation saves money, or that development generates revenue once the cost of creating the infrastructure and services to sustain it are factored in. “Has there ever been a restructuring or amalgamation or annexation that has been specifically designed to enhance rural lifestyles or rural values? These things are invariably launched and promoted by people who favour some kind of grand growth scheme. If we keep going like that we aren’t going to have a forest, a wildlife preserve, provincial parks, the escarpment, or anything else like that. They won’t exist.”

Caledon councillor Richard Whitehead pooh-poohs such concerns. The region grew by one million people in the past twenty-five years and did it in a controlled manner, he says. “Can we have a sophisticated, well-planned community without subsidies from Peel?” As a partner in the GTA, Peel has elected to absorb almost another half million people in the next twenty years, of which Caledon’s share will be about 44,000 – four times the town’s population when it was formed in 1974. “[Peel] has been phenomenally successful in the context in which it was created,” Richard Whitehead says. “Why stop now and trade the car in?”

Rural immigration: Boom or Bust?

IN THIS EXCERPT FROM HIS BEST-SELLING BOOK, BOOM, BUST & ECHO, AN ANALYSIS OF CHANGING CANADIAN DEMOGRAPHICS, DAVID FOOT SEEMED TO HAVE THESE LOCAL HILLS IN MIND:

The shift away from the big cities means that the outlook is very promising for Canada’s smaller cities … ln Ontario, there will be a movement from greater Toronto to smaller cities to the east and west of the megalopolis, such places as Guelph to the west, Collingwood to the north, and Kingston to the east. These cities will have a chance to attract an influx of well-educated, affluent people who will expand the local tax base and make a positive contribution to the community, for example by supporting cultural and charitable causes. On the other hand, local municipalities will be faced with new costs associated with providing the serviced land and other requirements of an expanding population.

These retiring newcomers won’t want to settle in the centres of their new small cities. Most will be looking for five-to-ten-acre lots in the suburbs. Others will be attracted by new residential communities built around golf courses. Their arrival will create a major challenge for local politicians and planners: how to expand without falling victim to the sort of urban sprawl that would destroy the small-city charm that is among these cities’ chief assets. The front-end boomers will want a small-town atmosphere, but at the same time they are unwilling to give up such urban amenities as good restaurants and shopping. The cities with the best planners, who can figure out the best ways of balancing these conflicting demands, will win the contest to attract retiring boomers to the local tax rolls. Perhaps most important of all as the massive baby-boom generation enters its 50s and 60s will be health care facilities. Boomers are less likely to relocate to a community that lacks a top-notch hospital. Hospitals that are viewed as a financial burden in the mid-1990s will be an important economic development tool for some small cities and rural districts after the turn of the century. After 2010, many small communities will also be the sites of new retirement communities to house the World War II generation and the early boomers.

This demographics-driven movement back to small-town and rural Canada has important environmental implications. Rural land surrounding small cities is going to rise in value. Providing sewage, fire, and police services in formerly rural communities will be difficult. The pressure on farmland will increase. So will the pressure on forests and aquifers. These are priceless resources that must be protected for the generations to come. That should be done before the newcomers arrive, because once they are installed it will be much harder to impose new regulations. The time to start preparing for the movement of the boomers from the big cities to the small ones is the decade of the 1990s. Let’s not wait to be surprised by the inevitable once again.