Caledon forced to go it alone: Here’s why the odds and costs are against us

The Ford government’s dissolution of Peel and incursion into the Greenbelt pose existential threats to Caledon as we know it.

When planning expert Heather Konefat says the dissolution of Peel Region is “a disaster for Caledon on every front,” your ears should perk up. Konefat headed Caledon’s planning department for seven years, then moved to York Region in 2006 where she was in charge of planning until she retired in 2013. But retirement wasn’t in Konefat’s cards; she was immediately snapped up by her hometown of Brampton where she spent several years as a special planning adviser with a front-row seat on the region’s inner workings. “Peel’s dissolution will only result in a lower quality of life and higher taxes,” she says. “It’s the end of a way of life.”

Under Bill 112, the Hazel McCallion Act, passed in May by the Doug Ford government, Caledon, Brampton and Mississauga will become independent, single-tier cites on January 1, 2025. The move was a triumph for Mississauga which had been lobbying for independence from Peel for two decades, first under the late, long-serving mayor for whom the bill is named and then under current mayor Bonnie Crombie. Although Caledon, with a small fraction of Peel’s population and only three seats on the region’s 25-member council, has chafed at times under its minority role, it has consistently resisted proposals to dissolve the union – and with good reason.

Even before the McCallion Act, Caledon had been facing a crisis resulting from Bill 23, the More Homes Built Faster Act. Passed in November last year, the act set housing targets for 29 municipalities – including 13,000 homes in Caledon – and dramatically altered how municipalities can plan and finance that residential development.

Positioned as a response to a nationwide crisis in affordable housing and record-breaking federal immigration targets set at nearly 500,000 newcomers a year, nearly half of whom will choose to live in Ontario, Bill 23 aims to smooth the way for the construction of 1.5 million new homes by 2031. The bill exempts residential developers from paying municipal development charges on “affordable” homes, those valued at 80 per cent of average market value or less. Among other developer-friendly measures, it also drastically weakens parkland requirements, public input, environmental reviews by conservation authorities, and protection of cultural and natural heritage.

Coupled with the provincial government’s unprecedented use of minister’s zoning orders (MZOs), which allow it to override municipal planning decisions, and its award of “strong mayor” powers to the leaders of 26 municipalities, allowing them to veto majority decisions of their councils, Queen’s Park is diving deep into municipal waters.

Although willing to do its part to deal with Canada’s housing crisis, Caledon has expressed grave concerns about how the provincial government is proposing to go about it. A comprehensive report prepared by Caledon staff and presented to council last January offers a blunt assessment of the impact of Bill 23: “These legislative changes will impact the environmental, social and economic health and wellbeing of the town. Caledon will require the support of all levels of government, residents, and stakeholders to achieve its vision of smart growth and not lose sight of what matters to Caledon.”

Caledon’s housing target of 13,000 new homes by 2031 is only 1,000 more than the town was already planning. But as Caledon planning director Antonietta Minichillo explains, the majority of the lots designated for development are greenfield (i.e., unserviced land), which is the most expensive to develop. That’s because, as the staff report notes, greenfield development “is contingent on essential infrastructure being in place – roads, transit, utilities and water and wastewater servicing.”

And herein lies Caledon’s conundrum: Under regional government, Caledon’s infrastructure needs would have been built and paid for almost entirely by Peel Region. With Peel’s dissolution, Caledon may be on the hook for financing this infrastructure, dramatically compounding the effect of lost development charges under Bill 23.

In March, Caledon mayor Annette Groves told the Mississauga News that this growth would be so costly she worries her son and grandchildren would inherit the debt.

A forced pledge

When the McCallion Act comes into effect in 2025, Caledon won’t have the lowest population of any single-tier municipality in the province. Neighbouring Dufferin County, for instance, has fewer residents. But it will be the smallest single-tier municipality of the 29 that the province has required to sign a housing pledge to meet its aggressive growth targets.

And Ford is holding municipalities’ feet to the fire on the pledge by offering a pair of signing “incentives.” A municipality must sign the pledge to access the province’s still-unspecified financial support and to maintain the recently granted strong-mayor powers. While some mayors have declined the additional power, Groves has already used it twice – most recently to appoint Nathan Hyde as the town’s new chief administrative officer. Hyde was previously employed in a similar role in the town of Erin, where he oversaw development of a massive and highly controversial residential project.

The two bills pose a double-barrelled problem for Caledon. And that problem has its roots in the widely cherished belief that growth is good, when often it isn’t.

Instead, as Mississauga mayor McCallion told me in an interview almost 25 years ago, “Growth is bad for [Caledon] down the road environmentally as well as financially – but mainly financially.” Prophetically, McCallion advised Carol Seglins, Caledon’s mayor at the time, to get off the urban-growth treadmill because “the infrastructure that’s going to be required to service the leapfrogging of development [into Caledon] is going to be astronomical.”

Andrew Sancton, professor emeritus at Western University where he focused on urban politics and local government, explains, “If you had development charges that reflected the average cost of new growth, and you had intense development – infill and highrises – then the new units probably would pay for themselves. If [a municipality] had relatively low development charges and a lot of greenfield, single-family housing, it certainly wouldn’t pay for itself.”

Historically in Ontario the goal has been for growth to pay for growth. This required municipalities to sock away a portion of the development charges collected on new construction to pay for infrastructure needed for future growth. But with Caledon’s relatively slow increase in population to date and with Peel Region funding the bulk of the infrastructure the town requires, the municipality has little development-fund reserve of its own to finance the exorbitant costs of greenfield development.

The January staff report estimated that without financial help, residents could face a tax increase of at least 27 per cent, noting that once all factors are assessed, that number could be “exponentially higher.” Now that the McCallion Act has been added to the mix, Caledon isn’t even trying to estimate the additional impact on taxpayers. It’s waiting until next summer when the details of the dissolution have been worked out by the five-person, provincially appointed transition board.

Meanwhile, Brampton mayor Patrick Brown and Mississauga mayor Crombie are squabbling publicly about who owes what to whom in the breakup. Caledon is rarely mentioned in their debate. Nevertheless, it’s unlikely those municipalities will get off without being assigned some financial contribution to Caledon.

All 12 MPPs in Peel Region are members of the Ford government, so it could be a delicate balancing act for the premier to keep all their constituents onside, more so because former Ontario Progressive Conservative Party leader Brown had vehemently opposed the dissolution and Crombie has announced her candidacy for the Liberal leadership.

Caledon’s only MPP, Sylvia Jones, occupies what is often called the safest seat in Ontario. As deputy premier and minister of health, she almost certainly has the close ear of the premier. However, if Jones is mindful of the threats facing Caledon, she has made no public comment on the matter.

Doubts about the “whole” thing

Since announcing the McCallion Act, Ford has repeatedly promised he will keep all three municipalities “whole.” It’s a term Minichillo interprets to mean financially whole, but how much and for how long is still a wide open question.

“Not yet knowing how we’re going to be made whole causes some significant concern for municipalities,” Minichillo says. “Given the changes in the current political environment and the higher use of MZOs, for example, we lose much of the ability to help shape the zoning and what that community could look like. So there could potentially be a lot at risk.” It’s not just the baseline infrastructure like roads and utilities that developer fees support, she says. “Development charges help pay for parks. They help pay for community centres, recreation facilities, fire halls. Without certainty around those pieces, we could be missing those critical ingredients of even life and safety in our communities.”

In response to such concerns, on July 26 – eight months after passing Bill 23 – the province announced it had hired Ernst & Young to examine the finances of six municipalities to “provide a clear and shared understanding of the impacts of changes to development-related fees and charges included in the More Homes Built Faster Act.” Tellingly perhaps, four of the six municipalities included in the study are Mississauga, Brampton, Caledon and Peel Region. (The others are Toronto and Newmarket.) The audit has been welcomed by both the development industry and the municipalities involved, but it does raise the question: Shouldn’t these impacts have been determined before Bill 23 and the McCallion Act came into law?

They will come, but will we build it?

And there’s another hitch. The municipality investing in infrastructure may have assurances from developers that they will build, but as Ontario is finding out, speculators haven’t been as eager or as able to put shovels in the ground as expected, despite Bill 23’s generous incentives. As Minichillo notes, the town can provide the serviceable lots, but it can’t make developers build.

In July, a CBC report found the 29 municipalities with mandated targets are well short of where they need to be to meet the Ford government’s goal of 1.5 million new homes over the next eight years. Many argue the goal is unattainable. Experts blame rising mortgage rates and a shortage of construction workers. (It’s estimated Ontario will require an additional 72,000 construction workers by 2027). Talk of a recession doesn’t help, nor does the already high cost of housing in the GTA. Furthermore, the required infrastructure, especially transit and wastewater plants, can take years to plan and build.

“How do we pivot quickly to respond to the province when these projects are multi-year projects, multibillion dollar projects?” asks Minichillo. “I think there’s a significant disconnect there that everybody is struggling with.”

According to its 2015 to 2035 Strategic Plan, Peel Region has invested billions, much of it borrowed money, to fund the infrastructure developers require. With an annual budget of $3.1 billion, 7,000 employees and a triple-A credit rating, the region has been resilient to economic swings, prompting Konefat to remark, “The region is a tremendous resource for providing shelter from a storm.” She then asks the obvious, “Who is going to take the risk of building infrastructure without Peel?”

Groves is well aware of Caledon’s dilemma. In an interview on TVO’s The Agenda, she told host Steve Paikin that Caledon can’t afford to go it alone. With a current population of 80,000 compared to about 1.5 million in Brampton and Mississauga combined, Caledon has had a good deal as the junior partner in the region. Chief among the advantages of having a wealthy caretaker is that, based on its population, Caledon currently pays only about 5 per cent of the costs of water, wastewater, regional roads, public health and myriad other services supplied by Peel. The rest is picked up by Brampton and Mississauga – which, of course, is why Mississauga is so desperate to get out.

In that long ago interview, McCallion predicted that significant growth in Caledon would compromise Mississauga because the massive investment in Caledon’s greenfield infrastructure would coincide with repairs to her city’s aging infrastructure and the reduction in development charges resulting from slowed growth as Mississauga ran out of space.

Looking for a new dance partner

In 1975, when the County of Peel was transformed into the Region of Peel, one of several regional governments established in Ontario in the 1970s, the logic was that regional government would create economic efficiencies by consolidating certain functions and services for a group of lower-tier municipalities. That trend to amalgamation continued into the 2000s under the Common Sense Revolution of Conservative premier Mike Harris. So Ford’s sudden announcement to dissolve Peel is both unprecedented and surprising.

It’s unprecedented because breaking up a region has never been done by fiat in Canada. (Montreal and Headingley, Manitoba, for example, de-amalgamated but only after residents supported the move in referendums. Results have been mixed.) And it’s surprising because the dissolution was done with no public consultation despite a 2019 poll in which only 30 per cent of Peel residents supported it and a mere 20 per cent in Caledon were in favour. What’s more, the McCallion Act took away the possibility of Caledon amalgamating with a different partner, such as Dufferin County or York Region.

In the TVO interview, Groves said she met with the premier in advance of the McCallion Act and he was “open to the idea” of a new partner for Caledon. No explanation has been given for the government’s failure to heed Groves’ plea despite a pair of 2019 reports commissioned by Peel Region. Completed by Deloitte and Ernst & Young, they predicted dire results for Caledon. Deloitte concluded that because of its modest tax base, “Caledon would face significant financial challenges and is not viable on its own.”

TVO host Paikin picked up on Groves’ description of Caledon as the child in the middle of a tense divorce between Mississauga and Brampton. But rather than a typical breakup in which the fight is over who gets custody, neither “parent” wants Caledon, given its burden of growth. Still, Groves said she had received the premier’s assurance that he would look after Caledon.

How that assurance plays out remains to be seen, but both Groves and Minichillo insist that the only viable, long-term solution for the town is for growth to continue to pay for growth. Hence the town’s request that greenfield development be given special dispensation because of its exponentially higher cost.

Like Caledon, other affected municipalities are also petitioning the province to rethink its development charge exemption, as well as it definition of affordable housing. They argue that the two things perversely create a significant disincentive for municipalities to pursue the higher-density, lower-cost housing and transit-oriented infrastructure the province claims it wants. The ostensible goal of the exemption is to make homes more affordable by eliminating developers’ fees from the construction cost.

In Caledon the average house price is $1.6 million, so by the government’s definition of “affordable,” the exemption kicks in on homes valued at up to $1.3 million. This definition replaces the historical one that tied affordability to average income. The province has agreed to clarify its definition of affordable housing by this fall, but even if it does, as the Caledon staff report notes, Bill 23 “offers no strategies to ensure that any cost savings resulting from the proposed changes are passed on to homebuyers.”

It’s not just about money

But the challenges the two bills pose to Caledon go well beyond financial considerations. While concurring that “Ontario needs to build more of the right kind of housing in the right locations and at the right price,” the staff report adds pointedly, “Housing alone does not create a community.”

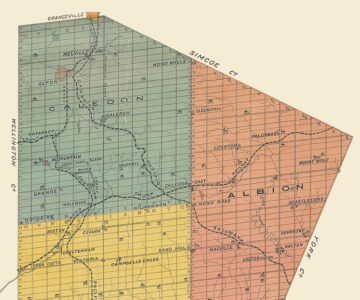

Since amalgamation, Caledon has been cautious and strategic in its growth. Long before 2005 when the Liberal government of Dalton McGuinty introduced Places to Grow, a detailed provincial growth plan that specified population and density targets to a horizon of 2021, Caledon had adopted a tri-nodal approach to combat sprawl.

Caledon East, Bolton and Mayfield West were to take most of the new residential development with the idea they would develop into “complete communities” – ones with a mix of housing where residents can live-work-learn-play without climbing into a car. Minichillo acknowledges that goal remains largely unfulfilled, especially in Mayfield West where cars line the streets and fill the driveways of single-family houses, and there is no central core where residents can congregate and create a community.

When she came on board in March 2022, Minichillo says, “Caledon was not planning Caledon. Other people were planning Caledon.” Asked what she meant by “other people,” she said she meant developers. “The quality of housing we were seeing was the lowest common denominator.” But she doesn’t lay all the blame at the feet of the developers. Many developers will build what they can get away with, and the town was letting them do it. “Developers could submit anything,” Minichillo says, “and as long as it met bare minimum criteria, we would work with it.”

To remedy the situation, Minichillo says she and town staff worked hard to create new standards and terms of reference that must be addressed in a development application. As a result, she says, “We’re getting better environmental reports. We’re getting better commercial reports, planning justification reports, urban design reports. We actually have some standards around those pieces and we hadn’t had those before.”

Gunning for the Greenbelt

What Caledon has successfully achieved through the years is its 80–20 split between rural and urban land, keeping the countryside largely intact. It has helped that since 2005, most of the town has been protected within the embrace of the Greenbelt. The town’s hamlets and villages dot a unique landscape – one where the Niagara Escarpment butts up against the Oak Ridges Moraine, where the Credit and the Humber rivers course their way south, and all sweep toward the rich farmland of the Peel Plain.

The environment is a “huge lens” for the town, says Minichillo. “We have official plan policies that ask for the protection of the Greenbelt. Even in our housing pledge we were very clear that the Greenbelt is critical and should remain intact.”

But with the Ford government’s recent incursions into the Greenbelt, swapping out 7,400 acres for lands, most of them already protected, elsewhere, that might not be easy – a situation the staff report anticipated: “While no land is proposed to be removed from the Greenbelt in Caledon now, these changes are concerning as they may set a precedent that other environmentally protected lands can be opened for development.”

At this writing, Ford is vowing to stand by his Greenbelt boundary changes, in spite of a scathing report in August by Ontario’s auditor general, Bonnie Lysyk, and an RCMP probe into “irregularities” with the government’s process. According to Lysyk’s report, “Provincial government actions in 2022 to open parts of the Greenbelt for development failed to consider environmental, agricultural and financial risks and impacts, proceeded with little input from experts or affected parties, and favoured certain developers/landowners.”

Fuelling longstanding opposition claims of backroom deals between the Ford government and developers, the report added, “Further, we noted that opening the Greenbelt was not needed to meet the government’s goal of building 1.5 million homes over 10 years” and that the changes lined the pockets of certain developers with an estimated $8.3-billion increase in their property values.

But there may be signs the government is blinking. As the staff report anticipated, Ontario housing minister Steve Clark issued an MZO this summer to expand a planned residential development at the southwest corner of Old School Road and Highway 10 into the Greenbelt. In the wake of auditor general’s report and strong objections from Caledon, the province backed down and reversed its decision.

Nevertheless, threats to the Greenbelt are not the only thing that stands in the way of protecting Caledon’s countryside and securing the town’s green future. The Ford government has also dramatically limited the role of conservation authorities in development planning.

Unique to Ontario, the conservation authorities manage the province’s rivers across municipal boundaries on a watershed-wide basis. Created some 75 years ago after the catastrophic flooding of Hurricane Hazel, their role has evolved to protecting the overall health of the watersheds, a task exacerbated by rapid urbanization in the GTA.

With Caledon’s significant environmental features, says Minichillo, “We relied on conservation authorities to do all of our development review for applications and they did a wonderful job … That development review function was now placed on the town. And the town had no environmental planners to do this work and no expertise with which to undertake it.”

In response, Caledon has hired Michael Hoy, the town’s first manager of parks and natural heritage, to take on some of the conservation authorities’ former responsibilities, with any overload going to consultants. Although the watershed-wide perspective has been lost, Hoy has been tasked with creating the town’s first natural heritage strategy. Among other things, Minichillo says, the strategy will introduce innovative stormwater management practices, enhanced tree protection, and wildlife corridors. “We are also creating green development standards,” she says. “There’s a lot on the green agenda, and it’s frankly a passion of mine and very important to me personally and professionally.”

Caledon is also mindful of the commitments it made in a memorandum of understanding with the Mississaugas of the Credit First Nation in October 2022 as part of the town’s reconciliation efforts. The First Nation officially opposes Bill 23 because it was passed without consultation, particularly on matters related to its impacts on treaty rights, land claims, the Ontario Heritage Act and environmental protections.

Mushrooming beyond 2031

The bottom line, Minichillo says, is “We cannot grow in irresponsible ways that don’t look at environmental outcomes, social outcomes and financial outcomes for the town. So we’ve created a growth management and phasing plan that’s also paired with a fiscal impact assessment.” The growth plan will be released as part of the town’s official plan when that document is finalized.

And it’s not just the next eight years that are challenging the town’s vision of itself. The official plan looks to a horizon of 2041, by which time the province has mandated Caledon to nearly double its current population to 150,000 – and beyond that to mushroom again to 300,000 by 2051 – enough growth to add a city the size of Burlington within the town’s borders.

Inevitably, much of that growth will occur on south Caledon’s Peel Plain where prime agricultural land, woodlands and river valleys were left out of the Greenbelt in a swath commonly referred to as the Whitebelt. The environmental repercussions of paving the Peel Plain have already been well documented by a broad coalition of opponents to the proposed Highway 413 – which would also swoop through the Whitebelt (and tip into the Greenbelt). Although the controversial highway project is on hold while the federal government conducts an environmental assessment, in a manner that is becoming familiar under Premier Ford, the province has already erected huge road signs demarcating the route as though it were a done deal.

Ian Sinclair was a Caledon councillor for 10 years before he retired in 2022. A municipal policy wonk who has been called the town’s green champion, Sinclair says, “There’s no business case for breaking up Peel.” While congratulating the town’s planning and financial staff for doing an excellent job, he predicts Caledon residents will be hit hard by the combined impacts of Bill 23, the dissolution of Peel, unprecedented growth and Highway 413. “The combination of threats and challenges is staggering,” he says. “It’s like walking off a gangplank into thin air.”

Related Stories

When Caledon Was Made: Tales of Conflict and Triumph From the Early Days

Sep 8, 2023 | | HeritageA rural route by any other name? Where to put the blue bins? A memoir from Caledon’s first public works architect.

Finding Balance in Caledon: The Urban/Rural Divide

Jun 16, 2015 | | EnvironmentIn less than two decades Caledon’s population will be 75 per cent urban. Can its countryside values survive the shift?

10 Years of the Greenbelt

Jun 16, 2015 | | EnvironmentOntario launched the Greenbelt Plan’s 10-year review, which is taking place concurrently with reviews of the Niagara Escarpment Plan, the Oak Ridges Moraine Conservation Plan & Places to Grow.

The Greenbelt: Letting the Belt out a Notch or Two

Mar 21, 2010 | | EnvironmentShould the Greenbelt be expanded? The central purpose of the plan is to protect farmland and environmentally sensitive land on the urban fringe.

I wish that instead of breaking up the three municipalities contained in the region of peel, the province would amalgámate them all under the region of peel. Then they could all share in the intended development for the whole area. mississauga and Brampton could finance their infill and repairs, and caledon could continue the tri-nodal development it had planned. In this way, financing would be shared on a priority basis that the region would decide. One big happy region – but I’m dreaming!

Rita baldassarra from Orangeville on Sep 19, 2023 at 8:36 am |

This article should be required reading for all CALEDON residents

The merging of the needed history and the recent history and todays news is vert well done

Nicola Ross dud a great job here

Thanks fir a great article

I hope he keeps updating this work as the story continues and the politics potentially change…and targets change since few people will agree that 1.3 million dollar homes are affordable to most new home buyers or pensioners

Tim

Timothy J Donovan from Caledon East on Sep 9, 2023 at 6:06 pm |