Alison and Jim

Although her life is separated from artist J.E.H. MacDonald by nearly a century, Alison Douglas has come to know the painter with microscopic intimacy.

Orangeville resident A.J. Douglas is never called that. She is, happily, Alison.

On the other hand, Group of Seven co-founder, artist and educator J.E.H MacDonald is almost exclusively remembered as J.E.H, not by his given names, James Edward Hervey. But to Alison, conservator at the McMichael Canadian Art Collection in Kleinburg, holders of the largest trove of the Group’s works, he’s just “Jim.”

This casual intimacy, nearly a century after MacDonald’s death in 1932, comes from Alison’s exhaustive and decidedly un-casual examination of his works, methods, writings and travels, detailed in the recently published J.E.H. MacDonald, Up Close: The Artist’s Materials and Techniques, which Alison co-authored with conservation scientist Kate Helwig.

Alison may not use initials before her surname, but does have impressive ones after it: BFA (bachelor of fine arts) and M.A.C. (master of art conservation), both degrees from Queen’s University.

And prior to her more than two decades at the McMichael, Alison interned or worked at renowned Canadian cultural institutions that are also commonly known by their initials: ROM, VAG and AGO. (Royal Ontario Museum, Vancouver Art Gallery and Art Gallery of Ontario respectively.)

Alison describes her career as an art conservator as “a weird niche – highly competitive.” She estimates there are fewer than 100 art conservators in Canada, all working at midsized to large institutions, such as the National Gallery of Canada which employs several.

On most days, taking care of the 6,500 art pieces in the McMichael collection (of which less than 2 per cent might be on display at any one time) is Alison’s dream job.

A painter herself when she finds the time, seeing the work of artists she particularly admires, such as Emily Carr (“Her work feels alive to me”), up close is a treat and a privilege. “Being hands-on, looking through the microscope at them,” delighting in “the materiality of paintings, the physicality of them” are sustaining joys.

Although the job also has a prosaic side: deadlines, workload and “the business of art” – generating gallery revenues in a competitive marketplace – Alison says, “When we unpack a show, pull out the work and look at it, it is like opening gifts at Christmas. Art books are great, but there is something about standing in front of an actual work and seeing how the colours are mixed, the brushstrokes, how they have gotten a particular effect…”

And she feels a special affinity with the Group of Seven and their associates. “I love to camp. I love to canoe. I’m an outdoor Canadian. That’s my connection to the Group of Seven. There is a Varley painting that I love – Stormy Weather. It’s in the National Gallery. It reminds me of a feeling I get when I’m out on Georgian Bay.”

J.E.H. MacDonald was familiar with Georgian Bay, and with Algoma, Algonquin, Lake Superior and many other scenic and, in his day, difficult-to-reach Ontario locales. (While others in the Group of Seven, such as A.J. Casson and Franklin Carmichael, painted in the Headwaters region, there is no documentation of MacDonald having done so.)

As the book relates, MacDonald made his painting journeys “by foot, [railway] handcar and canoe.” Alison’s journeys of conservation and exploration among his works and others in the McMichael collection are made, as she says, with her “eyes, experience and material science.”

Her work as a conservator is threefold: managing exhibitions, co-ordinating loans and acquisitions, and conservation of the artwork itself.

“We loan out our works. Institutes borrow from each other. Right now we have five different loans going in five different directions.”

Each loaned work includes a report, involving a physical examination and an assessment of its condition. To maintain that condition, the temperature, light, humidity and gallery security similar to the McMichael’s is demanded anywhere the art is destined.

“I assess to see instabilities – flaking, paint loss, cracking. We do physical treatments for travel and display. Every work has a condition report it travels with, so the conservator at the other end can look at it and see if there is any change.”

McMichael has an annual budget for the purchase of new works. Some other works come in on loan from other institutions or private collections. Sometimes wealthy patrons are approached and asked kindly if they will purchase something specific for the collection or an exhibition.

Among Alison’s conservation responsibilities are maintaining the soft illuminance and 50 per cent relative humidity in all gallery spaces at the McMichael. Asked if such a carefully maintained and gentle environment, designed for optimum art preservation, is also good for her personal preservation? Alison laughs and admits, “It’s good in the winter.”

With all the diligence and meticulous care involved in maintaining and displaying art on the walls of the McMichael, how personally does Alison take inadvertent damage or willful vandalism on her watch?

“I’d feel we failed in our duty. But stuff happens. We’re pros and can fix it. It is the balance between protecting the art and hanging it so that people can love it and react to it. We know that. We are doing our best.”

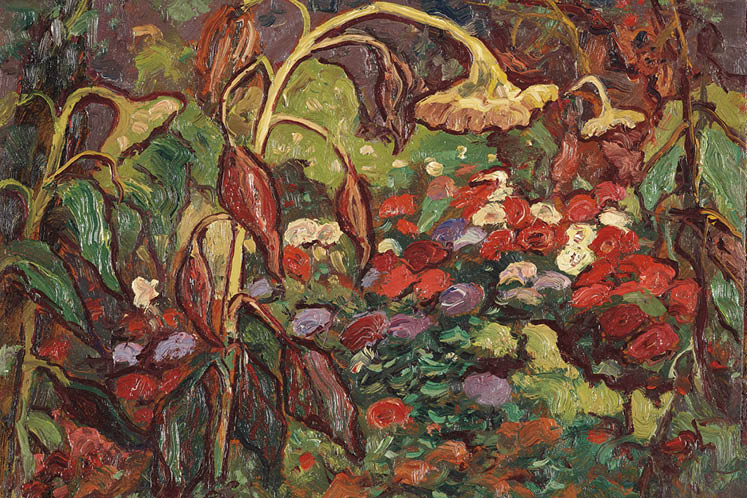

J.E.H MacDonald did his best, painting from Toronto’s High Park and wilderness locations across Canada to the beaches of Barbados from 1909 until his untimely death at age 59.

Reserved and introverted, co-founder and oldest member of the Group of Seven, MacDonald produced 100 to 150 larger studio works in addition to 600 to 800 oil sketches. All in pursuit of the Group’s vision of creating art that represented Canada’s iconic natural landscapes.

The sketches, small panels, completed in two to three hours (sometimes three or more a day), were the artist’s rough notes created en plein air – by a sylvan lake, atop a windswept cliff, in the snows beside a rushing river.

While lacking the finesse and polish of his studio works, MacDonald’s small oil panels are rich in vitality and immediacy. In his handwritten notes for an outdoor sketching class, appended to the book, he advises: “Don’t photograph the subject. Give only the characteristic details essential to the composition.” He adds, “Speed helps in sketching just as in sprinting. Try to grasp the idea of your subject quickly. Then put it down before you can form any doubts about it.”

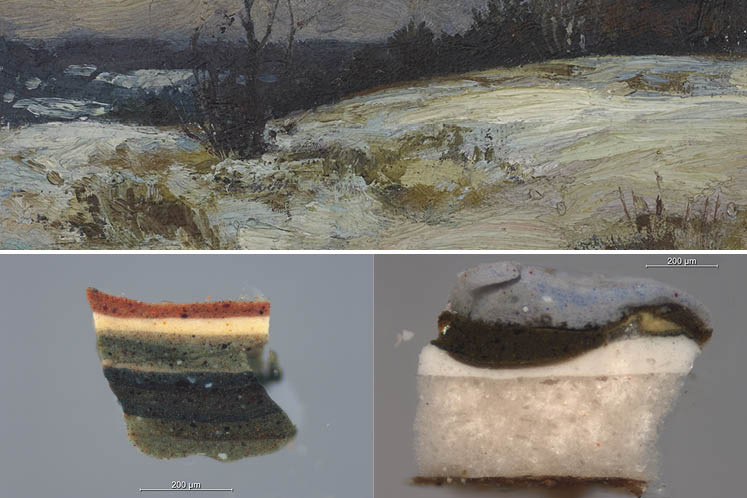

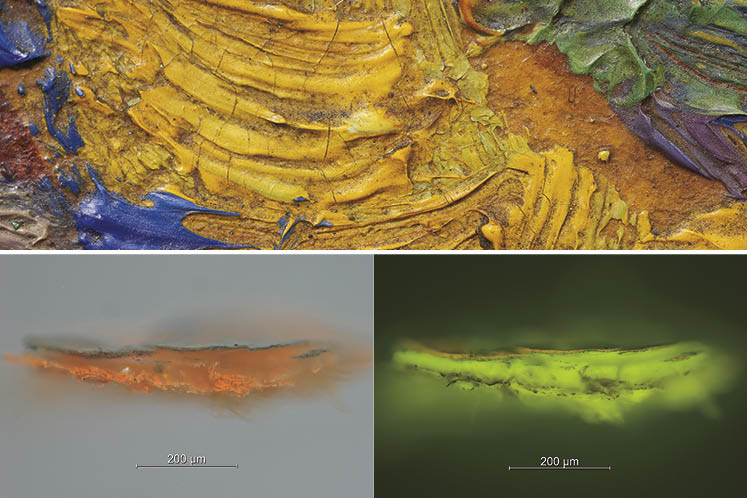

In J.E.H. MacDonald, Up Close, Alison and co-author Kate Helwig, who works at the Canadian Conservation Institute in Ottawa, were privileged to intimately examine 32 works by MacDonald, both sketches and studio work, including his most famous, The Tangled Garden, a large and stunning depiction of the artist’s own Thornhill garden.

They felt honoured. “That was an amazing moment,” Alison says. “[The Tangled Garden] never comes off the wall at the National Gallery of Canada. It came off for us.”

Described as an “interface between art history and science,” the book details in words and photos ten years of the authors’ work in which, as Alison describes it, they took “a deep dive into MacDonald’s techniques and materials.” Their work included minute, sometimes microscopic and molecular examination of every physical facet of MacDonald’s art, from his brushstroke technique and the materials he painted on, to an exhaustive analysis of the pigments he favoured, along with a study of his diaries, letters and lectures. Of particular import were century-old sales catalogues of artists’ materials in use at the time.

For non-art nerds, the two conservators’ professionalism might seem taken to arcane extremes. As a random example, from page 168: “The first techniques applied to the paint ground samples were FTIR spectroscopy, and SEM/EDX.”

(Translation: Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy – a technique to measure how much light a sample absorbs at each wavelength; and scanning electron microscopy/energy dispersive X-ray spectrometry – used to determine the base elements and chemical components of a sample. But if you find that boggling, don’t worry, there’s an extensive glossary and appendix to help you along. )

The most important goals of all this forensic analysis are to understand an artist’s creative process, establish chronologies, and enhance conservation. Alison says, “It’s about looking at a piece and figuring out why it’s in terrible shape. Or a contemporary piece made with, say, silicon rubber. How this thing is going to age? How are we going to take care of it? There is a lot of that kind of sleuthing. I love that!”

In the introduction to the book, the authors note, “The data will also be valuable to scientists, curators, art historians and collectors when questions arise about authenticity.” Indeed questions about authenticity would arise in 2015 when the Vancouver Art Gallery announced the acquisition by donation of ten hitherto unknown J.E.H MacDonald sketches, one a preparatory study for The Tangled Garden itself.

Almost immediately some in the field questioned the paintings’ attribution. A planned show was postponed. An investigation began. Independently and coincidentally, Alison and Kate were already hard at work on their studies of MacDonald’s works and methods.

In a final chapter of the book titled “Applying the Research,” the authors note that authentication can be a complicated process, relying on provenance records, comparisons with an artist’s usual style, materials and methods, and science. Using the VAG sketches and other works as examples, the chapter liberally deploys such words as “inconsistent with,” “uncharacteristic” and “atypical” – but always with the caveat that human creativity is not necessarily linear or predictable. Still, in the case of the VAG sketches, it was science that ultimately allowed for a decisive “gotcha” moment.

Citing a work titled Sketch after The Tangled Garden, the chapter concludes, “The use of multiple anachronistic pigments in various parts of the composition showed that J.E.H. MacDonald did not paint this sketch.” Specifically it notes, “Phthalocyanine green (Pigment Green 7) was discovered in 1935 and pigment production began in 1936, four years after MacDonald’s death.” Ultimately all 10 of the VAG sketches fell victim to what Kate calls “the smoking gun” of that green pigment.

“This is incredibly rare, this result,” says Alison. “A pigment found outside the artist’s lifetime. That is definitive. That was Kate and the CCI. They deal with authentication issues all the time. They have the facilities, very specific, very expensive, to do that deep scientific analysis.”

Publication of Alison and Kate’s book was timed to coincide with an exhibition called ‘J.E.H. MacDonald? A Tangled Garden’, currently on at the Vancouver Art Gallery until May 12. Note the question mark in the show’s title. Duped, but not embarrassed, the VAG embraced transparency and included the faked sketches in the exhibition, detailing the process of the acquisition, investigation, and revelation of fraud.

Alison had not seen the sketches until she attended the Vancouver show in February. There she had a chance to test another important but more subjective factor that goes into authentication: connoisseurship. It is the instinctive knowledge seeded through prolonged exposure to an artist’s style and techniques. Challenged to pick out the fake sketches intermingled on the walls among legitimate works by MacDonald, she pegged nine out of 10.

After 154 pages of diligence, professionalism and rigorous science, the book ends with delightful humility, verging on humour: “We feel compelled to point out that the spirit and the poetry of [MacDonald’s] art can never be captured through this type of analytical exercise.”

In a phone interview, Alison adds wryly, “I think we both fundamentally know that the reason people love art is not for the type of board it is painted on.”

So a final serious question is posed to her: “Is passion incompatible with what you do?”

“It is a different kind of passion,” she responds. “A passion to protect the legacy of the art and the artist and have it there for many generations to come and be inspired by.”

Related Stories

Painted in Peel

Sep 15, 2004 | | ArtsThe Group of Seven found much to inspire them in the hills and villages of Caledon. This fall, the Peel Heritage Complex mounts a major exhibition of works by the Group and their contemporaries.

Michael Compeau

Sep 20, 2022 | | ArtsMichael Compeau’s paintings are inspired by the lush landscapes and natural wonders that surround him.

Lynden Cowan

Nov 20, 2022 | | Artist in ResidenceLynden Cowan’s highly detailed hyper realistic paintings require “triple-zero brushes by the boxload” to achieve.

Linda Jenetti

Mar 23, 2014 | | Artist in ResidenceHer show La Campagnola – the country girl presents paintings and sketches inspired by the rolling hills of both Umbria and her long-time home in Mulmur Township.