Wild Nocturne

Grab a flashlight and head out on a hike after sundown and get to know the creatures of the night – including moths, salamanders and frogs.

At six years old, Eloise MacNeal is already a talented salamander hunter. I met Eloise and her family on a rainy night in April at an escarpment pond pulsing with life. The spring peepers were at their strident best, creating a throbbing wall of sound as I approached the pond. But the squeals of Eloise rivalled those of the peepers. She would release a delighted shriek with each salamander she found. Her 11-year-old brother, Desmond, was equally excited, though not quite as vocal.

Nighttime explorers Dan MacNeal and his son Desmond. Photo by Don Scallen.

I’ve known Dan MacNeal, Eloise and Desmond’s dad, for years. A rural resident who lives just south of Orton, he is a naturalist with a jealousy-inducing penchant for finding rare birds. As I watched his nature-besotted children at the pond, I reflected on the gift he’s giving his children. He’s planting the seeds of nature appreciation, a gift that may flower into a lifelong passion that will draw his children outdoors to a world of fresh air, exercise and, above all, wonder.

Of course, nurturing a passion for nature doesn’t happen only after dark, but the thrill of heading into the woods or to a wetland with flashlights in hand is hard to beat. Moreover, the night is populated with exciting creatures that usually can’t be seen or heard during the day. Fiona Reid, a good friend who wrote and illustrated the latest edition of the Peterson Field Guide to Mammals of North America, touts the night as “a little-explored realm of nature, where it is easy to make new discoveries and witness things that very few people have seen.”

Much of the natural world operates on a schedule opposite to ours. We humans are diurnal animals, creatures of the day, and most of us hesitate to leave our well-lit abodes and venture into the woods after dark. We don’t feel comfortable when the night compromises our vision. Our eyes lack the abundance of light-gathering rods that help many animals, including owls and raccoons, see very well in the dark. For much of our evolutionary history, we’ve been vulnerable to predators whose night vision is superior to ours. The big cats are an example of those. Turn off the lights, and our tension grows. Every cracking twig conjures thoughts of monsters.

This primal fear continues to shape our behaviour today, even though, here in Headwaters at least, walking through a forest at night is no more dangerous than it is during the day. If humans have a primal fear of the dark, we also have the ability to reason. And reason should tell us that we have little to fear by venturing out after the sun sets. A nature lover who overcomes this fear will be rewarded. Creatures that fly, sing, crawl and flutter abound after dark. There are the salamanders of spring, the moths of summer and the singing insects of autumn. Owls call almost exclusively after dark, as do whip-poor-wills. Caterpillars of kaleidoscopic form and colour crawl from their hiding places, and frogs croak, snore and peep.

Salamander hunter Eloise MacNeal. Photo by Don Scallen.

When it comes to frogs, night is the best time to see many of the 10 species that inhabit these hills. People who live on the outskirts of Headwaters towns or villages, or in the countryside proper, know the voices of spring peepers, though it’s likely few of us have actually seen one. On many sunny afternoons, I’ve stood among peepers and tried to spot even a single singer. And many times I haven’t seen any. But after dark my success rate soars. Perhaps the flashlight is key. With my vision restricted to the very defined patch of light illuminated by its beam, extraneous distractions, plentiful during the day, are blacked out. Or perhaps it’s simpler than that. Maybe the peepers sneak out of their hiding places under the cover of darkness.

A visit to a spring peeper pond in the evening is a great adventure, if you can bear the ear-splitting cacophony of the chorus. A calling peeper will soon be found. You’ll marvel at the remarkable volume produced by an animal that could sit comfortably on a loonie.

Spring peeper. Photo by Don Scallen.

Spotted salamander. Photo by Don Scallen.

Another wonderful frog, best sought after dark at its breeding ponds, is the grey treefrog. These lovely creatures can be their namesake grey colour, or brown or just about any shade of green. Wannabe chameleons, they have a tool box of fascinating adaptations, including the ability to change colour. In Headwaters, grey treefrogs are just as widespread as spring peepers, and their loud trills overlap with the piping of their smaller relatives in May, then continue into early summer. The males are easy to approach in the dark and, like star performers illuminated by spotlights on stage, they often continue to sing in flashlight beams. Their adhesive toe pads allow them to cling firmly to branches overhanging the ponds, making for great photo ops.

The spotted salamanders that Eloise and her brother were agog over appear only after dark, and their window of activity is brief, roughly from the last week of March through to mid-April in this area. On moist nights or evenings after unseasonably warm days, they wend their way through the woods to reach ponds. Witnessing this annual migration is magical. Spotted salamanders are beautiful, and though common in forests and fishless ponds, they are seldom seen.

Eloise and her family visited the pond at precisely the right time. Rain, and lots of it, had fallen earlier in the day and the ground was sodden – perfect travel conditions for soft-bodied salamanders that need to keep their skin moist.

My guess is that Eloise and Desmond will remember this salamander evening with great fondness for many years. And who knows? Perhaps they will reprise this adventure with their own children years from now.

Most of my nocturnal nature adventures are enjoyed with others. The camaraderie of a communal wildlife search has great appeal. Any nagging anxiety at being outdoors after dark evaporates in the company of friends. And there is joy in shared discovery.

American woodcock. Photo by Robert McCaw.

But don’t entirely dismiss the idea of going solo. This also has appeal. In April I ventured out on my own to find an American woodcock. This portly bird goes by a number of colourful aliases including the delightful “timberdoodle” and the decidedly less-flattering “bogsucker,” both monikers derived from its fondness for probing mud with its dagger-like beak in search of worms and other choice edibles. Woodcock males become animated at sunset, engaging in weird and wonderful courtship displays.

The evening was still and cool, and the sky clear as I made my way to the woodcock fields. Bare trees were silhouetted in the orange light of the setting sun. Song sparrows, newly arrived from the south, served up a melodic counterpoint to the yips and howls of a distant coyote family. A field sparrow chimed in. In the nearby woods, a screech owl began to trill. High above, a crescent moon floated in the darkening sky. Between it and the beacon of Venus, a descending Orion, the hunter, blinked into view on its way to its summertime residence in southern skies.

At about 8:30 p.m. I found a male woodcock, intent on impressing resident females by chirping his characteristic “peent” as he strutted around on his grassy staging arena in the meadow. After uttering 20 or so “peents,” he launched himself upward in spiralling flight. Circling above me at perhaps 100 metres in the air, he then dropped sharply back toward his arena, releasing a series of discordant notes all the way down. Back on his stage, he repeated the process: “peents,” skyward flight and then a rapid tumble back to Earth.

Solo experiences like this, in the wonderful milieu of a darkening sky on a quiet evening, transport me briefly to a place removed from the cares of everyday life. Aloneness in nature is a reflective time, a chance to silently ponder the mystery and the awesome mechanism of the universe, expressed in the flight of woodcocks or the movement of constellations.

I’m reminded of another solo nighttime nature adventure I had 20 years ago. I started by visiting Doris Bourne, a naturalist friend, in Alton. She was a wonderful woman, now departed and greatly missed. She had a kettle on the boil and fresh-baked cookies on the coffee table. As night descended, we sat and chatted about ravens and snakes. Doris was no stranger to going solo in nature. For years, even into her 80s, she would camp alone in Algonquin Park and fall asleep to a nocturnal symphony of loons, barred owls and bullfrogs.

After catching up with Doris, I bade her goodnight, and lifting my bike from my car, rode off into the night. I biked until dawn on quiet rural roads in my Caledon territory for the Ontario Breeding Bird Atlas project, listening for the calls of nocturnal birds. The early June night was redolent with the scent of lilac and chokecherry. Lest you think I was taking a foolish risk by riding through the night, know that I had lights on my bike, front and back. As a further precaution, I would pull my bike to the side of the road every time an infrequent car came by.

On my midnight ride, I heard screech owls and added black-billed cuckoo to my bird list when I heard one in the wee hours of the morning. The big payoff, though, came at about 3 a.m. when I heard an unfamiliar chatter coming from a wet field on Shaws Creek Road. The incessant voice suggested wren, and after considering my options, I knew I had a sedge wren, an uncommon bird in this area.

Now two decades later, with the third breeding bird atlas project underway, I’ll repeat my night ride. But alas, this time I won’t be able to kick it off with coffee, cookies and conversation at Doris’s house.

After the woodcocks and salamanders of spring, the search for moths lures my friends and me into the darkness. There are roughly 10 times as many moths as there are diurnal butterflies, and contrary to popular belief, many are pretty – and some are spellbindingly beautiful.

Fiona Reid’s curiosity about the natural world extends well beyond the mammals that were the focus of her graduate studies. Over the past decade she has become a regional expert on moths, and on her property in north Milton she has to date tallied more than 600 species. Fiona notes, however, this number pales in comparison to the 1000-plus species tallied by the High Park Mothia, a group of moth zealots in Toronto.

Mothing with a bedsheet and mercury vapour light. Photo by Don Scallen.

Hologram moth. Photo by Don Scallen.

Fiona happily shares the secrets of the art of mothing: “A moonless warm night in summer is ideal for moth activity, especially if there has been a light rain earlier and the air is still. A few days before, we will concoct a bait of brown sugar, beer, mashed bananas, perhaps some very ripe peaches, leaving this to hubble and bubble to perfection. Then we paint this tasty mixture on trees along a trail.”

After an hour or so, Fiona and her fellow mothers return to check each bait station and “try not to shout with joy should a lovely underwing moth be encountered.” Some moths are startled by loud noises and flutter for cover.

Fiona recommends using headlamps instead of flashlights in the mothing quest. “Using a headlamp leaves one’s hands free, but it also illuminates exactly where you want the light to be and reflects the eyeshine of many species.”

Sugary bait isn’t the only way she attracts moths. She also exploits the well-known attraction moths have for light. “I throw an old white bedsheet over my clothesline,” she says, “and illuminate it with a small UV light or a mercury vapour light.”

Spiny oak slug moth caterpillar. Photo by Don Scallen.

The caterpillars that transform into those moths are also worth seeking after dark. “For all the caterpillars and other insects we may discover during the day,” says Sam Jaffe of the Caterpillar Lab in New Hampshire, “there are countless thousands that go unseen. In sunlight and under the watchful eyes of predatory birds, most caterpillars fully invest in their defences, disappearing into their background with fine-tuned bark and leaf camouflage or disappearing altogether into bark crevices or shallow soil. But after dark, when birds are no longer searching, the insect world comes alive and relaxes those visual defences.”

The Caterpillar Lab is a nonprofit organization with a mission to convince people of the wonder and ecological value of caterpillars. Inside their storefront in downtown Marlborough, hundreds of species of caterpillars are raised, and the lab’s popular outreach programs educate thousands of people every year.

Most of the caterpillars housed at the lab come from nocturnal caterpillar forays. Sam Jaffe is a huge booster of venturing into nature after dark: “The nocturnal world of insects is explored by far too few, considering the bounty it offers. Start with a stroll around your backyard, get hooked, and become a night-owl naturalist.”

My friends and I are hooked. The caterpillars we find at night are wildly diverse and often delightfully bizarre. Hunting them in native trees such as oak, elm, basswood and black cherry is an activity best done communally. The more eyes on the prize, the better. Highly anticipated are the cries of “Found one!” Pulses race.

In recent years I’ve found another way to while away an hour or two after sunset. Singing insects such as crickets and katydids have captured my heart. Many of these species call during the day, but some are dedicated nocturnal performers. Night prompts their music making.

I’m surprised I didn’t pay much attention to these night singers previously. They provide the soundtrack of sultry summer evenings. They can be plentiful, even in suburban settings, and they are far more than just your typical black crickets. Tree crickets, for example, are not at all like the crickets that sneak into our houses to chirp from nooks and crannies in our basements. They are a diverse group of mainly arboreal insects represented by about six species in Headwaters. Unlike the heavy-bodied ground crickets, tree crickets are delicate, slender creatures. But that daintiness is deceiving. They are remarkably loud.

Tree crickets sing by raising diaphanous wings over their abdomens and rubbing them together. Nature offers infinite examples of beauty but seeing these singers in action is breathtaking. This, however, takes patience. Tree crickets typically press mute as you draw near, but the irresistible urge to beckon prospective mates soon trumps caution, and they sing again.

Last fall I captured a few of these diminutive insects and set them up indoors, furnishing them with branches to climb on and plenty of food. Sliced apple was a hit. I misted their enclosures from time to time and then waited for dusk to cue their voices. This allowed me to sneak up quietly to view the singers, and it also helped me use their distinctive calls to identify the species. Beyond that, it was a delight to turn off my music and television, and be serenaded by the calming trills of the crickets. Please know that I kept each cricket no more than a few days. Then I returned him outdoors where he could continue to woo females.

I’ll leave the last ringing endorsement of becoming a “night-owl naturalist” to Desmond MacNeal, brother of Eloise, the salamander hunter. “Going out at night gives me a thrill unlike exploring the world in daytime,” he says. “It reminds me that even when you’re asleep the world around you is not. Each time I go out to see and hear those creatures, I’m just as excited as the last time, and by the end of each expedition, I learn something new and have a lot more questions about the lives of nocturnal animals. I will never forget these nights.”

Life abounds after dark, much of it glorious in form, sound and colour. Adventure beckons, as Desmond knows. So why not put the online world on pause, muster a little nocturnal daring and see what you can find?

Editor’s note: A change has been made from the print version of this story to correct the spelling of Dan MacNeal’s name.

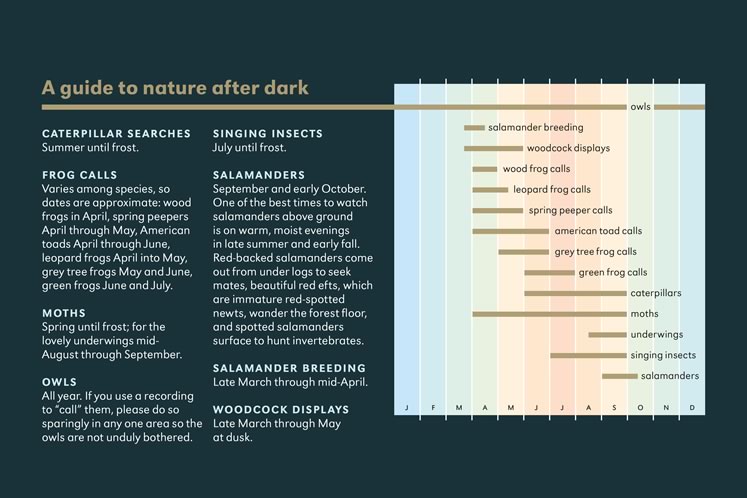

A guide to nature after dark

Caterpillar searches

Summer until frost.

Frog calls

Varies among species, so dates are approximate: wood frogs in April, spring peepers April through May, American toads April through June, leopard frogs April into May, grey tree frogs May and June, green frogs June and July.

Moths

Spring until frost; for the lovely underwings mid-August through September.

Owls

All year. If you use a recording to “call” them, please do so sparingly in any one area so the owls are not unduly bothered.

Singing insects

July until frost.

Salamanders

September and early October. One of the best times to watch salamanders above ground is on warm, moist evenings in late summer and early fall. Red-backed salamanders come out from under logs to seek mates, beautiful red efts, which are immature red-spotted newts, wander the forest floor, and spotted salamanders surface to hunt invertebrates.

Salamander breeding

Late March through mid-April.

Woodcock displays

Late March through May at dusk.

Related Stories

Calvin the Salamander

May 4, 2021 | | Notes from the WildCalvin is a rare piebald version of a spotted salamander.

Hopping and Walkin’ in the Rain

Oct 15, 2020 | | Notes from the WildThis is the time of year to get out after dark and explore… especially as the rain falls.

Night Creatures

Oct 8, 2019 | | Notes from the WildMost of the nocturnal critters my friends and I find are insects, but spiders, millipedes and amphibians also appear in our flashlight beams.

Minnows

Jun 8, 2021 | | Notes from the WildMost of our minnows, like our songbirds, breed in spring and many male minnows, like male songbirds, advertise their reproductive fitness with brilliant colours.

Life Renewed

Apr 12, 2021 | | Notes from the WildThere is much to quicken the pulse at this time of year. So much to see, hear and appreciate.

While We Are Sleeping

Jun 22, 2021 | | CommunityIt’s 3:15 a.m. Where are you? Meet the folks who are doing important work in the middle of the night as most of us are curled up under the covers.