A Dairy Farmer’s Tale

His Jersey cows have provided Art Bracken with a good life. And as the community changes around him, the daily routines on his Caledon farm remain the same.

It’s late afternoon on a steamy August day. A familiar figure chugs along The Grange Sideroad in Caledon on a reliable old Massey-Ferguson. Dairy farmer Art Bracken stops the tractor at the end of his long farm lane to greet the mail carrier. He sifts through the mail she hands him. “All junk mail,” he says with disgust. But one envelope catches his eye. He opens it and scans the contents: “Oh Lordy, another Jersey sale. Another farmer’s selling out.”

Art Bracken shakes his head, not so much over the unstable economics of farming, but because the letter brings another sign that a way of life is slowly slipping away.

Art Bracken checks the mail: “Oh Lordy, another Jersey sale. Another farmer’s selling out.” Photo by Malcolm Batty.

Art Bracken has been raising purebred Jersey cows on his Glen-Caro farm for forty years. He lives with his wife Jean in the house his grandfather built. It’s the house he was born in more than eighty years ago and the house they raised their two children in. Etched into the stone on the nearby barn is the date 1893.

The house sits with business-like authority on a knoll in the middle of the farm’s long flat fields. The land is buffered to the west by the steep slope of the Niagara Escarpment and on the southern roadside by a line of old maples. Now, high on the escarpment, the sun glints off the windows of the country mansions of area newcomers. Along the road, many of the limbs on the maples are tattered and leafless. Maybe it’s just old age that’s killing them. Or maybe, as Art suspects, it’s the winter salt that has washed into their roots ever since the road was raised and paved a few years ago.

“I’ve seen a lot of changes over the years, not many of them good,” Art says. The worst one? “I don’t have any neighbours anymore.” But then he corrects himself, “Oh, I have neighbours. A lot of nice people, good people. But they’re a different generation. They have a different lifestyle. They’re not farmers. I’m the only farmer left here now – except for Jim Petch over on the First Line.”

He and Jim recently went and witched for water on a property near Dundas, Ontario. But such outings, comradely and purposeful, are rare these days. “We’re half lonely now,” he says. “We don’t have many people drop by to visit any more. There are not too many of our generation left.”

There’s a clear note of regret in his voice, but it passes quickly. There’s not much time for idle reflection when there’s a farm to run. And there is still very much a farm to run. Art has just completed the second cut of hay. He brought in 10,000 bales, in spite of this summer’s blistering heat and the rain and humidity that made the job drag on much longer than usual – and in spite of his doctor’s orders to slow down. Those orders followed a car accident three years ago in which both he and Jean were seriously injured and that left Art with permanent muscle damage and a steel pin in his leg.

He had to give up milking after the accident, but he’s still in the barn every morning by five o’clock to meet his farm hand Deb Kendall.

Deb is one of a new generation who chose to stay on the farm when most of her peers were heading to jobs in the city. Now in her mid-thirties, she runs a farm with her father a few miles from Glen-Caro on Kennedy Road. She grew up on a dairy farm and has never seriously considered any other way of life. That makes her a rare breed these days, especially among women. “There are other women out there working full time at farming, but they are few and far between,” she says.

She acknowledges the five o’clock starting time, with only Saturdays off, can be tough, especially on Sundays. During the summer, she brings in the cows with the help of her dog Frosty, milks about forty-five of them, turns them back out, and is home in time to get breakfast for her two children. She is back at Glen-Caro by three-thirty to begin the evening milking. The work is more rigorous during the cold and dark of winter when the full herd of more than a hundred cows and heifers are in the barn and need feeding and bedding.

The Glen-Caro crew: John Dunne, Deb Kendall and Art Bracken. John worked at Glen-Caro before Deb and now spells her on Saturdays. Photo by Malcolm Batty.

Deb has been working at the Bracken farm since last winter. Before that she had worked for ten years on another local dairy farm that had a mixed herd, mostly Holstein. The Canadian Holstein is acknowledged worldwide as a champion producer and its distinctive black and white markings have become synonymous with milk. (Hockey player Doug Gilmour’s black and white legs need no explanation in the Ontario Milk Marketing Board’s current television commercials.) A good Holstein will produce about 26,000 pounds of milk a year, Art says, while a Jersey comes in at around 15,000 to 18,000 pounds at the top end.

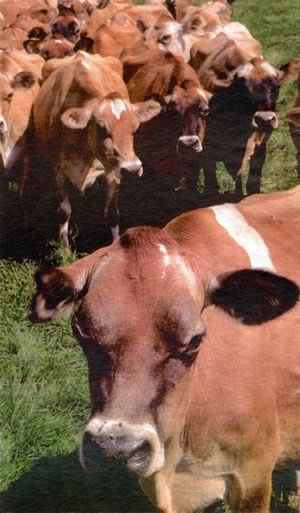

The Glen-Caro cows: Pretty, doe-eyed Jerseys. Photo by Malcolm Batty.

But Art is not striving for the top end. “You have to blow them right out of the stall to get that much milk. And, if you over feed them, you start getting other troubles like mastitis, and it’s harder to get them to calve.” He’s happy when his cows are producing 10,000 to 12,000 pounds annually. Nor has he ever experimented with dietary additives to boost production. “We’ve never come up to date on that stuff and I’m not going to change now.”

He started his Jersey herd after the war in 1947 when Jersey milk was in demand. With its high butterfat content, Jersey milk was sold separately and at a premium to individual distributors. Now, as Art says, “milk is milk.” It is all blended together and distributed by the milk marketing board. In spite of that Art remains loyal to his Jerseys, though he is typically pragmatic in his affection: “I don’t go around singing the praises of the Jersey, but they’ve done well for us. I like a Jersey. If it’s going good and hardy, it’ll take a lot of cold, a lot heat [without affecting milk production].” He defers to Deb to describe the character of his pretty, doe-eyed cows in more detail.

“They are a lot quieter than the Holstein. You get the odd crazy one, but if she steps on you, it doesn’t hurt nearly as much,” says Deb, who has had at least one hoof print turn blue and swollen on her leg. She knows every one of the Glen-Caro cows by name. “You get to know them first by their udder, then by their face,” she says. Her current favourite is Nan. “She’s pretty, she’s clean, she has a nice udder, she gives lots of milk. She’s a fancy looking little cow.” Deb explains that a “nice udder” is more than an aesthetic virtue. It’s high off the ground and the teats are evenly balanced, so it’s easy to clean them and attach the milking tubes. Another cow, Molly, is a different story: “She’s obnoxious. She likes to kick me, step on me, squish me, and swipe me with her dirty tail.”

There’s an easy rapport between Art and Deb, though Deb admits that for the first few weeks on the job, she was a little intimidated by Art’s gruff manner. “He didn’t talk to me for the first two months,” she says. But she’s a hard, efficient worker who won his respect and his friendship. “Now,” she says, “a lot of mornings I’m late getting started because we sit and talk. He’s full of great stories about the old days.”

The mutual respect is an essential ingredient to the successful management of the farm. It takes considerable organization to ensure the production quota assigned by the milk marketing board is met steadily throughout the year.

The cows ideally produce a calf a year. They are milked for about nine months after the calf is born, then “dried off’ for a couple of months before the next calf is born. Heifers are about eighteen months old before they are bred and brought into the cycle. Bull calves are sold to beef farmers. Art keeps one bull to breed his heifers – “the bull does a better job of catching them, and has a higher success rate with the young cows” – but the rest of the cows are impregnated through artificial insemination. Art says he hasn’t bought a cow for about ten years, relying on his own breeding program to replenish his herd.

The objective is to keep the milk flowing evenly throughout the year. Twice a day the milk runs straight from each cow through a network of tubes into a refrigerated stainless steel vat. It is picked up every other day by the milk marketing board. It sounds straight forward, but nature has a way of intervening. This summer, for instance, there’s been an unusually high number of bull calves born. That could spell a shortage farther down the line if there are not enough heifers to come on as the other cows are drying off. But too many milkers can also be a problem. If there’s more milk than the vat can hold on any given day, the surplus has to be dumped. Power outages and bacterial invasions can also destroy the production of a day or more.

Jasmine, a recent addition to the herd. All the cows have names. Photo by Malcolm Batty.

Art admits he has had milk rejected more than once as a result of the board’s rigorous inspection standards. But Deb says the farm recently received a citation for the consistently high quality of milk it was producing. “Once you’ve had one of those, you want to work harder to get it again,” she says. Her enthusiasm for the task shows no sign of waning, though she insists emphatically that she plans to retire from farm work when she turns fifty.

For Art Bracken, retirement is not in the cards. He has been financially secure for years and he knows full well the value of the real estate he farms. But the farm not only gives purpose to Art’s life, he has come to believe it literally sustains his life. After the car accident three years ago, Art spent more than two months in the trauma unit at Sunnybrook Hospital. For a while it was questionable whether he would pull through. But on the wall next to his bed was a picture of Glen-Caro farm. “It’s the farm that kept me alive,” he says with absolute certainty.

Related Stories

Dairy Herd SOLD

Mar 21, 2016 | | FarmingWith the dairy herd gone, a farmer’s daughter reflects on memory and identity.

Farmers at the Table

Sep 24, 2021 | | FarmingThree Dufferin farmers sit down talk about what it means to be a modern farmer, the challenges they face and what they wish we knew about them.