African Shadows

Black settlers were among the first homesteaders in the hills, but little of their legacy remains.

There’s almost nothing left to show they were here – those early settlers in the Dufferin area. But they were here, people of African descent, so many years ago, and so many miles from home, whether that home was as close as the Niagara frontier, in an American state, or as far away as Africa itself. Their local legacy has been overshadowed by the Scottish and Irish settlers whose descendants remained in this area.

In and around our hills, the history of early Black settlement is being rediscovered and preserved. Photo courtesy of Metropolitan Toronto Library

These hills lie next to Toronto, the most culturally diverse city in the world, according to the United Nations. Yet, it is only in recent years that a growing cultural diversity has begun to enliven the city’s neighbouring rural regions, including our own. With that diversity has come a new awareness of the roles played by people of many cultural backgrounds in the rural history of Ontario.

In and around our hills, the history of early Black settlement is being rediscovered and preserved. In Artemesia township, for example, just north of the Dufferin border, a local group called the Old Durham Road Pioneer Cemetery Committee has erected a memorial on the site of a Black graveyard at the corner of Grey County Road 14 and the Old Durham Road. The graveyard had been ploughed over in 1930 and planted in potatoes.

In 1995, in West Garafraxa township, along the Grand River, a plaque was erected to commemorate Richard Pierpoint, an African veteran of both the American Revolution and the War of 1812. Believed to be Garafraxa’s first settler, he established himself on the 1st concession in 1821, on land he had received as payment for his service in the War of 1812. (By 1829, the population of Garafraxa still numbered fewer than 80 souls.) Between the Pierpoint settlement and the Artemesia settlement sits Dufferin County, an area also traversed by early Black settlers.

Africans came into Ontario in three ways. Many were slaves of United Empire Loyalists. It wasn’t until the Emancipation Act came into effect on August 1, 1834 that slavery ended in this province. Others came as free men and women, although would-be settlers of African origin were not routinely given land grants in Upper Canada, as white settlers were after the American Revolution. However, a few Black men did receive grants if they had fought as free men with the British. Among them was Richard Pierpoint who had served with Butler’s Rangers and was one of only ten Black men on the United Empire Loyalist list. The other group of Black settlers were those who had escaped slavery in the States.

Many of the Black immigrants who did not receive land grants, or who were running from slavery, followed Ojibwa trails through southern Ontario, and settled. Here, out of the way of prying eyes and bounty hunters, they could raise their families in relative safety. Most of the reminders of these pioneers have disappeared as shadows disappear with the coming of clouds. When the provincial government became interested in settling these areas after the War of 1812, most Black homesteaders, with no legal title to their land, were obliged to move further north. Many of their descendants still live in the Owen Sound and Collingwood areas.

The government preferred to give land grants in this area’s newly surveyed townships to veterans of the War of 1812. They could be trusted to be loyal to the Crown.

These veterans included four men from the Coloured Corps, an all-Black unit based in the Niagara area. In addition to Richard Pierpoint, there was John Van Patten whose father had been a slave of Joseph Brant. But, by 1823, he had patented and sold his land in Garafraxa. He worked for the Secord family on Lake Ontario and had no reason to move here.

Another Coloured Corps veteran was George Martin who lived in Niagara. His father had been a slave of John Butler at one time and had also fought with Butler’s Rangers. George Martin’s land grant was for the west half of lot 7 on the 2nd concession east of Hurontario Street in Mono township. Like John Van Patten, he had no need to move to this area and in 1831 he sold his land.

The fourth Coloured Corps veteran was Robert Jupiter who had been brought to the Niagara area as a slave of the Servos family during the Revolutionary war. He eventually received his freedom, married and had two daughters and a son. During the War of 1812, he defended Canada as a sergeant in the Coloured Corps. As a reward for this service, he received a land grant for the west half of lot 15 on the 8th concession in the new township of Garafraxa. With a wife, children and work in Niagara, he also had no desire to settle here. He asked for a less remote piece of property but the government’s reply read, “Neither Mr. Mercer nor I could find a better lot for Jupiter than the one I have located, it is in the midst of a valuable township, though rather remote.” For those of African descent who didn’t have the advantages of war veterans, this remote area was a promising location.

Black settlers were among the first homesteaders in the hills, but little of their legacy remains.

Photo courtesy of Public Archives of Canada.

The census of 1851 lists some of the Black settlers who had made their way to the townships that now form part of Dufferin County. Andrew Hamilton, Gus Johnson, and John and Rebecca Brooks, all African-Americans, are listed in the census for the united townships of Arthur, Minto and Luther. George Lucas, an African-American, and his white, Canadian-born wife Mary were raising their seven children in Luther township. Another Black American, William Lewis, his Irish wife Bridget, and their six-year-old daughter Martha are shown as residents in the neighbouring township of Garafraxa. It is probable more Blacks were living in the area, but possibly the census taker, trudging through the wilderness, did not always find every new resident in the township.

Brothers William and Lewis Gant were two Black settlers who were not included in the 1851 census, but who are mentioned in The History of Dufferin County by Stephen Sawden, published in the late 1930s.

Around 1849, William Gant and his wife made their way from Toronto to Hall’s Corners and on to Beachell’s Tavern. Here they homesteaded fifty acres on lot 285 on the 1st concession S.W. of the Toronto and Sydenham Road in Melancthon township. Their family eventually grew to include five boys and three girls. According to Stephen Sawden, “Mr. Ghant [sic] often related thrilling stories of the ‘Slavery Days’ in the Sunny South before the immortal Lincoln achieved the emancipation of his race. Over fifty years ago the Ghants [sic] disposed of their property in Melancthon and moved to Lion’s Head.”

As a young man, William’s brother Lewis had been a sailor on the Great Lakes, travelling between Buffalo and Chicago. He later moved to Toronto where he was employed by Sir. W.P. Howland at the Lambton Flour Mills on the Humber River. He eventually left Toronto and followed the newly blazed Toronto Line to Sydenham Village (now Owen Sound) which had a growing Black population at the time.

The gravesite of Ann Gant mentions her husband Lewis, in St. Patrick’s Church, 280 sideroad, Melancthon. Photo by Peter Meyler.

Lewis had gone to Owen Sound to build a home and settle down. However, he returned to the New Survey of Melancthon and settled on the 2nd concession N.E., just above sideroad 270. He attended St. Patrick’s Church in Melancthon with his Irish wife Ann. Ann died in 1872 when she was forty-nine years old. Her marker in the St. Patrick’s churchyard is the only physical reminder of her husband. It reads “In memory of Ann, wife of Lewis Gant.” Lewis was said to have attended St. Patrick’s until his death around the turn of the century, but his gravesite, if it is in the churchyard, is unmarked.

Another unknown gravesite is that of George Hannahson. George’s mother was Hannah Ketchum, a white woman. In 1804, Hannah was living in Toronto with her brother Jesse when she had a relationship with a Black man. As a result of this relationship she had a son whom she named George. The Ketchums devised the surname of Hannahson for Hannah’s son. Any record of the boy’s father has been lost in time.

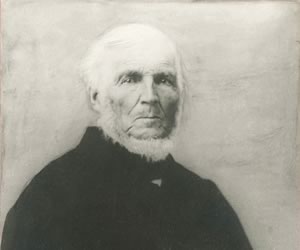

The Ketchums were a very well-known family in Upper Canada. Seneca Ketchum, a brother of Hannah, lived in Mono township. He was a staunch member of the Anglican Church and was the principal founder of St. Mark’s in Orangeville. Jesse, meanwhile, was a leading figure in the province in politics and philanthropy. He had property in both Toronto and Buffalo, New York.

Hannah and her son moved to the American city in 1845. About the same time, Mary Sanders, a Swiss woman moved to Fort Erie. By 1847, Mary had two small children and was a widow. Somewhere along the Niagara River, George Hannahson met the 20-year-old Mary. By 1848, they were married and had a daughter. Two years later, the growing Hannahson family moved to the Ketchum lands in Mono township. In 1857, George became the owner of the west half of lot 2, the 2nd concession of Mono. Here, George and Mary prospered as they raised their ten children. George died shortly after the birth of his last child in 1866. Mary lived in Mono for the remainder of her life.

The Orangeville Sun of May 8, 1890 carried the obituary of Mary Hannahson. In it, her ten children were acknowledged, but there was no mention of her husband George. His presence in the pages of this area’s history was already starting to fade, like so many others of African descent before.

Related Stories

Up to the Task

Nov 24, 2020 | | CommunityFour members of Shelburne’s Anti-Black Racism, Anti-Racism and Discrimination Task Force discuss their mission and the vision they have for Shelburne.

Making Black History in Caledon

Mar 24, 2020 | | HeritageA new museum exhibit called Our Voices, Our Journeys celebrates local black history through the personal stories of a Caledon congregation’s pioneering contributions to Headwaters.

The New Hope: Local Black Lives Matter Organizers

Nov 24, 2020 | | Local HeroesThese four young women (plus one younger sister) were the moving force behind two crucial local social justice marches – one in Orangeville and one in Shelburne.

Seneca Ketchum

Mar 23, 2015 | | Historic HillsSeneca was nearly 60 when he came to Mono, an age when many people look forward to ease and comfort.