Quick-Draw McGaw

For Laurie McGaw, whether it’s famous portraits, award-winning illustrations, or life in general, one word covers it: Real

Laurie McGaw had a nightmare once and I was in it.

It all started innocently enough. Laurie, one of Canada’s foremost portrait artists and illustrators, lives a few kilometres outside Shelburne. In my other life as an economic development consultant, I had been charged with the task of creating a new marketing logo for the town. Armed with a wealth of public input about what the image should convey, I approached Laurie about serving as the designer.

At first she had the good sense to hesitate, but I was persistent. I reminded her of the coin she designed for the Royal Canadian Mint in 2002, celebrating fifty years of Shakespeare at Stratford. “What about a logo celebrating your own town?” I went on, playing the guilt card.

That did it. “I really do love this community,” she said. “All right. Maybe I could take a look at what you’ve got …”

A child of the fifties in Etobicoke, Laurie and her brother Rob grew up exposed to the arts. She often visited the art department in her father’s printing company, McGaw-Jordan Ltd., Artists and Litho Plate Makers in downtown Toronto. Her father, Ted, was musical, collecting hundreds of classical and big band albums and later recording her brother’s folk-rock duo. Laurie’s mother, Carol, dabbled in painting, though crafts were her main creative outlet.

Laurie’s call to painting came at an early age. “It was when I was five and in hospital having my tonsils out,” she says. “The sixteen-year-old boy with a broken leg in the next bed had a drawing pad, and would draw constantly. He showed me how to make things look three dimensional. My dad bought one of his drawings for one dollar! I saved that in a special drawer and I still have it.”

Laurie graduated from Thistletown Collegiate Institute with a diploma in commercial art. In 1970 she went to work as a layout artist at her father’s firm. After a couple of years, she moved on, first to The Canadian Magazine and, in 1974, to Chatelaine. “In those years, I was exposed to the work of Canada’s great illustrators,” she says. “They inspired me to go into illustration.”

Among those mentors was Will Davies, a legend of the day. “He encouraged me to go back to school and go to the Ontario College of Art.” She graduated with an AOCA (Associate of The Ontario College of Art) in 1977. The next step was a job as an illustrator at TDF Artists Ltd. – then Canada’s largest advertising art studio.

In the late seventies, Laurie was living in a rented apartment above Embro’s Cookware Store on Yonge Street. On the advice of a friend, she decided to buy her first home, a row house on Berkeley Street, which was renovated into both home and shared studio space. She stayed for seven years.

One of Laurie’s early freelance clients was the Toronto Star, for whom she did courtroom drawings and weekly illustrations. Keith Richards of The Rolling Stones was one of her subjects when he appeared in a Toronto court on much-publicized drug charges. The Star gig also led to a bit-part on CBC TV’s Street Legal as a courtroom artist.

During this time, Laurie was also preparing portraits of both suspects and victims as a volunteer for the Metropolitan Toronto Police Homicide Division. Her work earned her a Civilian Citation.

Life was good when, in 1982, tragedy struck. First, her father died in January. Then, less than six months later, she also lost her brother Rob. “It was the worst day of my life,” she recalls of the day her brother died, a rare cloud crossing her face.

I go to Laurie’s house to go over a series of logo concepts that have been generated by students as part of a design competition at Centre Dufferin District High School. A bright, funny, infectiously engaging woman with a vast array of good stories to tell, I soon discover it’s impossible to remain uncomfortable around her for long. Our meeting stretches easily into a couple of hours.

Over the next several weeks I have the pleasure of watching Laurie explore design possibilities. From fifty or more sketches, gradually a selection of five is developed for consideration by Shelburne’s town leaders. One in particular is our favourite and, as it happens, the officials like it too. Now all we need to do final art.

That was easy.

The early eighties also brought brighter developments, though. A summer studying in Italy in 1983 and a couple of summer workshops in 1984 with Daniel Greene, one of America’s foremost portrait artists, were “life-changing events,” Laurie says, “artistically inspiring beyond measure.”

Many years earlier in 1969, a young man named Ross Phillips had begun working for the family firm and became friends with Laurie’s brother. “I was the sixteen-year-old teeny bopper hanging out with my four-year-older brother’s friends,” she recalls. Though they dated several times while Laurie was in her twenties, it wasn’t until Ross and Laurie met again on New Year’s Eve of 1984 that things really took off. They were engaged on Valentine’s Day and married that June.

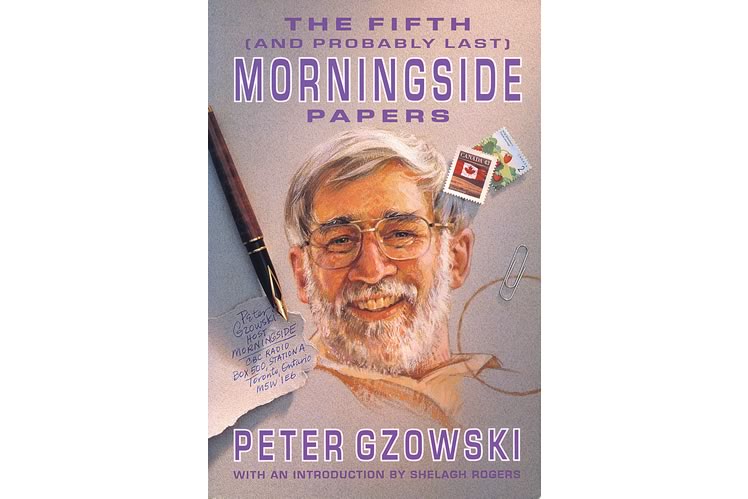

Laurie’s work continued to gain attention and by the mid-eighties she received a commission to paint Peter Gzowski, long-time CBC radio host, for the cover of his best-selling Morningside Papers book. The assignment eventually led to a total of seven Gzowski portraits – four more book covers for what became the Morningside Papers series, and two versions for CBC t-shirts and coffee mugs. It also resulted in a long personal friendship with Gzowski, whom she clearly adored.

In 1990, three years after their daughter Gwynne was born, the young family moved to a five-acre lot in Mulmur Township that had once belonged to Laurie’s parents. A pioneer log cabin on the property was removed and Ross, by now a contractor, built a new home on the site. Their son Owen was born in 1991.

In the early nineties, Laurie illustrated a children’s book called Polar the Titanic Bear, written by Daisy Spedden. The book tells the true story of a stuffed bear and his American family who survived the sinking of the epic ocean liner.

True to her childhood nickname, “Quick-Draw McGaw,” Laurie completed the entire book in only five months. A finalist for the 1994 Governor General’s Award, Polar the Titanic Bear has now sold more than 680,000 copies worldwide, has been translated into five languages, and is set for another reprint. The success of the book led to a “chain reaction” of illustrations for other children’s books, Laurie says.

A few days go by and, strangely, I don’t hear anything from Laurie. Eventually she drops by with a small mountain of sketches. “This is waking me up at three in the morning,” she says, “I just can’t seem to get the final artwork to sing.”

With a background in graphics, I’ve created a few logos myself, and I get what she means. There’s a certain moment when you just know it works. In the Shelburne case, it’s fair to say, that moment was proving elusive.

We set to collaborating, Laurie with her sketch pad and me with my keyboard. Versions spawned versions. Daily meetings, phone calls and e-mails are followed by hours of drawing. That magic moment, however, remains maddeningly just out of reach.

It’s not that what we were producing was bad. We like to think any number of our designs would have been acceptable. But when you’re creating a logo for the community you live in, mediocre won’t cut it. The goal was to create something we could feel proud of.

Days turn into a couple of weeks as the process slowly continues. We gradually become comfortable debating and negotiating with each other with gloves-off abandon.

One night, Laurie has a night-mare in which she’s driving into Shelburne, seeing her own butt-ugly logo on the entrance sign, horrified and helpless to change it. The experience is clearly traumatic. “Entrance-sign-nightmare potential” becomes a new design standard.

We gradually become more and more obsessed, determined not to be beaten by the phantom Shelburne logo. We explore so many different design approaches that we evolve our own method of intercommunication between hand-drawing and computer, an intricate process involving black-and-white laser prints, sheets of overhead projection film and red markers.

Our spouses, who are becoming old friends in their own right, form a mini support group – for each other, not us. They share their misery and keep statistics on the number of times per day we each ask their opinion on some tiny, yet to us terribly important, detail. I’m told they considered the potential need for intervention.

Still, nothing. Not so easy.

While illustrating children’s books has been an ongoing passion, Laurie’s real love is painting people. Portraiture has remained a constant in her career.

Her remarkable ability to identify a characteristic pose or expression, and render it with extraordinary warmth and realism, is what has made her work known across the country.

“I like to think that my work tells a story, captures a moment, or reveals something about the inner qualities of a person,” she says. “Artist and illustrator N.C. Wyeth, who illustrated stories with rich, painterly images, and portrait painter John Singer Sargent, with his deft brushwork and artistic genius, inspired me equally to pursue realistic, figurative art.”

Though still in the prime of her career, Laurie’s list of former subjects reads like a who’s-who of Canadian society. Among them: David Suzuki, Conrad Black and Barbara Amiel, Wayne Gretzky, Silken Laumann, Terry Fox, Farley Mowat, and the entire Board of Directors of Imperial Oil.

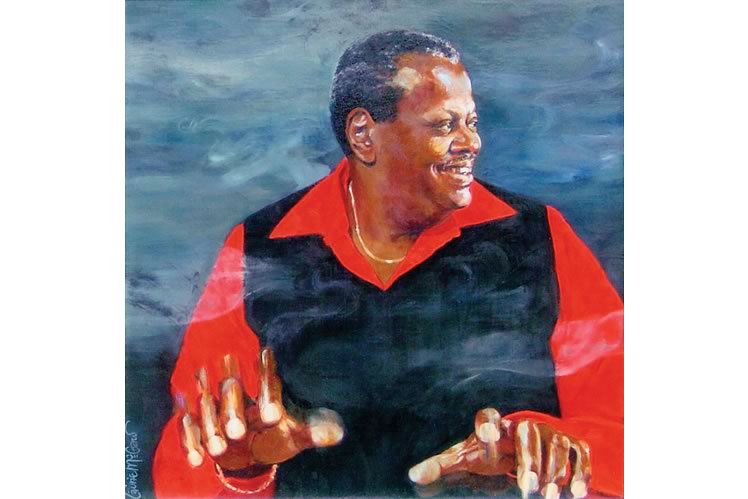

The proposed Portrait Gallery of Canada has expressed interest in her painting of Norman Jewison. Two professors at the University of Toronto purchased, then donated her portrait of Oscar Peterson to hang in the new Oscar Peterson Residence at the University of Toronto. Other celebrities she has painted, with a local connection, include David Nairn, Mark DuBois, Dan Needles, Tamara Hope, Dini Petty, Bruce Westwood and Gene DiNovi.

Since moving to the area, Laurie’s contribution to the local art scene has been significant. She was a founder and board member of The Dufferin Arts Council. She was chair of the Headwaters Studio Tour for a year and a participating artist for over ten. The Old Downtown Gallery in Orangeville and The Burdette Gallery in East Garafraxa both exhibit her work. And this year, adding to her already long list of awards, the Hills of Headwaters Tourism Association named her “Artist of the Year” for a second time.

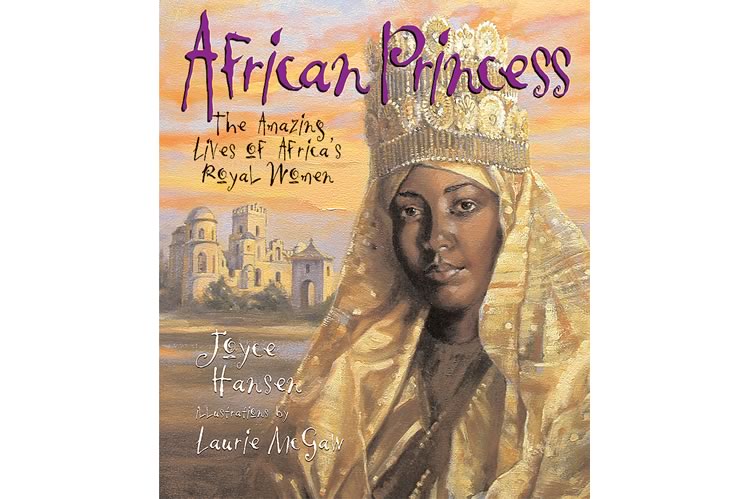

Now with thirteen children’s books to her credit, recognition of Laurie’s talent as a book illustrator has also continued to grow. A recent New York Times review described her illustrations for African Princess as “stunning.”

It’s Sunday, late in the afternoon. The phone rings. It’s Laurie with a one-word exclamation: “Eureka!”

“I have to come over right away,” she adds.

She arrives at the front door carrying a portfolio, and a six-pack of beer. Really good beer.

I know she’s serious.

The success of the 2002 Stratford coin has led to further commissions from the Royal Canadian Mint. Laurie designed the outer ring of a coin mark-ing the 2010 Vancouver Olympics, for which she used several local people as models. Ironically, she doesn’t actually have an example of the final product. While the coin has a $300 face value, it retails for $1,500. Even the artist doesn’t get a free sample.

Canada’s 2007 proof silver dollar was also adapted from one of Laurie’s drawings, an image of Thayendanegea, also known as Joseph Brant, a late 1700s warrior chief of the Six Nations tribe in the Grand River Valley.

One of her other coin designs was recently subject to controversy. Intended to celebrate arctic exploration, the twenty-dollar coin was criticized for depicting a “dark moment in Canadian history.” It featured Sir Martin Frobisher, his ship the Gabriel, and an Inuit man in a kayak. An Inuit group complained that the image was a sad reminder of Frobisher’s 1576 abduction of an Inuit hunter to England, where he who soon died. Not what an artist likes to hear about work that has been forever cast on a metal coin.

However, the debate took a dramatic turn when it was pointed out that Frobisher had taken the man in an effort to bargain back five members of his crew believed to be held in a nearby Inuit village. They were never seen again. “If indeed it is a ‘dark moment’,” quipped a Globe and Mail editorial, “its gloom is cast equally.”

Though many faces in Laurie’s paintings are widely familiar, the famous are by no means her only subjects. A current client, for example, is a Toronto investment banker named Bryce Bradley. Faced with a large blank wall in a downtown condo, she has commissioned Laurie to create a huge canvas, four feet wide by nine feet tall. Ross has built a set of wooden stairs in Laurie’s studio so she can work on the whole canvas at once. The painting will feature Bryce – a thirty-something woman who was once a stand-up comedian – riding an elephant.

Driven to create, one of Laurie’s favourite activities is a Wednesday night life-drawing session which she attends with about ten other artists at Elizabeth Babyn’s studio in Bolton. Having worked as a part-time in-structor at the Ontario College of Art in the late eighties, she continues to teach locally, conducting portrait-painting workshops and master classes to small groups throughout the year.

At long last, Shelburne’s logo is born.

After bouncing ideas off old friend and art director Dermot O’Brien, suddenly the solution presents itself. Just like Laurie, I know the instant I lay eyes on her sketch that it’s the one. It has the iconography. It has the colours. It has the shape. It works big. It works small. It works embroidered on a baseball cap.

More than that, both of us really like it. The glassy-eyed spouses do too.

Family and friends take up a lot of Laurie’s life these days. Gwynne is a student in the drama program at the University of Toronto, so there are regular trips to performances in the city. For Owen, an honours student at Centre Dufferin District High School, university isn’t far off. Ross’s mother, Kathleen, lives nearby in Shelburne, and can often be found with Laurie at Theatre Orangeville productions. (Laurie’s mother died in 1998. A long-time Mulmur weekender, she had moved to Shelburne in her latter years so she could also be near the family.)

In the rare idle moments between Ross’s busy life as a building contractor, and Laurie’s career, the couple can be found on their twenty-two foot sailboat on Georgian Bay.

What comes next? The dreams are plentiful. Building a smaller house when the kids are gone is a possibility. Travel. Painting portraits on the streets of Venice. One thing seems certain though: art will, as it always has, remain a constant.

Months later, the good people of Shelburne seem happy with their new logo – more than 90 per cent of respondents to a town website poll either “liked” it or thought it was “very attractive.” We mark the successful conclusion of our project, and the survival of our marriages, with a cele-bratory dinner in my kitchen. A soothing Creemore Springs balm helps our spouses bring closure to their support group.

Laurie says, “You know one of the best things Gzowski ever told me? He could tell I was nervous about being around celebrities. He took me aside and said, ‘Don’t be too uptight about the celebrity thing. They’re all just people too.’”

Though far too modest to admit it, Laurie McGaw has earned her own place among Canadian celebrities, but she still happily sees herself as “just people,” too.

Related Stories

Shelburne: A Town in Transition

Sep 16, 2017 | | CommunityAccording to Statistics Canada, Shelburne is Ontario’s fastest-growing town – and for residents old and new, that’s mostly a good thing.