Shelburne: A Town in Transition

According to Statistics Canada, Shelburne is Ontario’s fastest-growing town – and for residents old and new, that’s mostly a good thing.

It’s hard to know what William Jelly, founder of Shelburne, would make of the town today.

The small rural community, Dufferin County’s second largest urban centre, has long played second fiddle to Orangeville. But Shelburne made national news this year as the fastest-growing town over 5,000 in Ontario, and the second fastest in Canada, behind only Blackfalds, Alberta. Between 2011 and 2016, Shelburne’s population grew by 39.1 per cent, to 8,126 from 5,841. Currently about 8,500 people call the town home.

Indeed, the only previous time the town has experienced such dramatic growth was during Jelly’s day. Founded in 1865 as Jelly’s Corners and renamed Shelburne a year later, by 1869 the population had grown to 70. Over the next eight years there was a boom, and by 1877 the population had swelled to 750.

An aerial view of downtown Shelburne. Between 2011 and 2016, the town’s population grew by 39.1 per cent, to 8,126 from 5,841. Currently about 8,500 people call the town home. Photo by Rosemary Hasner / Black Dog Creative Arts.

But then growth slowed. By 1901, the year after Jelly died, the population stood at 1,188. For the next half century it remained essentially frozen – in 1951 the population was 1,184. If there was a newcomer, it was likely a farmer retiring to town.

At the 1951 Shelburne Fall Fair, you could still enter a hog-calling contest, though for women there was an alternative: a husband-calling contest. It was also the first year of Shelburne’s legendary Canadian Open Old-Time Fiddlers’ Contest. Broadcast live on CBC Radio for decades, it provided the town with a few days of national glory every summer.

It wasn’t enough to keep the young people around though. Like many small-town kids, they most often left to seek adventure in the big city. Although that hasn’t changed much, young families and others are flocking to Shelburne by the thousands, precisely because of its small-town lifestyle.

That tide is likely to continue as housing prices and congestion escalate in the GTA. Projects already in the works will see the population increase to 10,000. And the town is two years into an environmental assessment of an expansion to its sewage treatment plant. If approved, the town could grow to 14,000.

Though 800 new homes have already been built and the municipal workforce has grown only marginally, residents have not seen a decrease in property taxes. Instead the town is investing the additional revenue in capital projects, and those required for further growth. Several streets in the old part of town have been rebuilt. The arena, library and fire department have gone through expansions, and the police department is next.

Shelburne is stretching into the countryside with developments like this one at the northeast edge of town. About 800 new homes have been built in recent years, and sold out quickly to eager buyers, many of them from the GTA. Photo by Rosemary Hasner / Black Dog Creative Arts.

From a business and employment perspective, the town is also growing. Gone are the days when Dufferin Oaks Long-Term Care Home was the largest employer. Now not only the town’s but the county’s largest employer is KTH Shelburne Manufacturing. It provides more than 500 jobs, and Dufferin Board of Trade reports more than 80 per cent are local people. Since 2014 more than $50 million has been invested in expanding the plant, which supplies parts to Honda’s sprawling Alliston operation.

And bottled water company Ice River Springs recently relocated its head office to Shelburne from Feversham. Co-owner Sandy Gott says the company made the move so it could attract talent from larger population centres to the south. Overall, the Shelburne plant employs 115 people. Its innovative plastic bottle recycling operation, also located in Shelburne, is undergoing an expansion that will permit processing of 400,000 bottles per hour, up from 350,000. Ten additional jobs will be created.

John Telfer, who retired as Shelburne’s chief administrative officer in August, reports anecdotally that the number of home-based businesses has also risen, among them a significant number of Google and Microsoft professionals who work from home.

The downtown is also enjoying renewed vitality. A fresh crop of owners has begun to take over some of the buildings, with their sights set on renovation. Intensification is the hot buzzword.

The historic town hall, with Grace Tipling Concert Hall on the second floor, remains a jewel of Main Street and the venerable Jelly Craft Bakery, for years the only place in the heart of town where you could buy a latte, a sweet treat or midday meal, continues to thrive. But some new draws have begun to pop up, including such eateries as Healthy Cravings Holistic Kitchen, Fiddleheads, Beyond the Gate and the Dufferin Public House. An enthusiastic booster of the town, Chris Petersons, proprietor of “the Duffy,” lives in Hockley Valley, or as he prefers to call it, “suburban Shelburne.” The licensed restaurants are a particularly welcome addition in a town where it has been hard to enjoy a drink with dinner in any establishment other than the Legion.

A commercial area is planned for the east side of town, and there is hope the population has now grown large enough to attract some chains and big box stores. The town has long struggled to tempt any of the approximately 7.8 million vehicles that pass through every year, on their way to and from Collingwood or the Bruce Peninsula, to stop and shop. Borrowing a page from Orangeville, the strategy is to appeal both to day trippers with a prettified downtown as well as the “which-way-to-Walmart” crowd.

Though the town’s growth is the result of years of planning, like elsewhere in the GTA, the real estate market has been sizzling, and the new subdivisions sold out very quickly.

Prices have skyrocketed too. Realtor Lynda Buffett reports of the 134 homes sold in Shelburne in 2012, a little more than 80 percent were listed under $300,000, with the highest sale price at $388,000. By this year, the numbers had reversed. Of the 144 houses sold in the first seven months, 93 per cent were listed for more than $300,000, and the top price had shot up to $740,000.

One place 1870s William Jelly would be right at home is Shelburne town council, which is all white and all male. However, while council may not yet reflect the true face of Shelburne’s blossoming diversity, the school system does. As does the population of the new subdivisions where the old mold of a conservative, white farm community no longer applies. Lots of those newcomers still commute to jobs in the GTA, though as one of them, Alton Stephenson, points out, given gridlock in Toronto, his hour drive to Mississauga is no worse than for many who commute across just a small part of the city.

I connected with a cross-section of local residents to find out what sort of impact such rapid growth is having on the town.

Nearly everyone I encountered identified one particular deficiency: a shortage of recreational opportunities, especially the lack of an indoor pool. While the town has invested in some facilities, such as the arena expansion and upgraded baseball diamonds, there’s a demand for a wider range of programming to keep pace with the needs of girls, seniors and different cultural groups.

All the drive-through traffic that snarls downtown and the need for a bypass are other oft-repeated gripes – first raised in the middle of the last century.

Journalist Tom Claridge grew up in town in the 1940s, and three generations of his family owned the Shelburne Free Press and Economist from 1903 until he sold it in 2012. For much of that time, he says, the paper had an editor but no reporting staff. “News came in through the front door, literally. There was a mail slot for that purpose.” He recalls how the county-owned Dufferin Oaks came to be located in Shelburne, giving the town a rare win in its one-upmanship with Orangeville.

The county jail in Orangeville regularly housed 12 prisoners, of which only one or two had actually committed a crime. The rest were destitute people, often with dementia. The province eventually forced the county to provide more appropriate accommodation, and a battle ensued between Shelburne and Orangeville over where to build it. Orangeville’s proposed site was next to the railway tracks, and in those days a dozen trains a day passed through the town. Claridge says Shelburne loudly proclaimed Orangeville wanted to “put the old folks on the other side of the tracks.” Its argument must have held sway; Dufferin Oaks opened in Shelburne in 1962.

Claridge highlights an irony of the town’s expansion. “There’s been all this growth, but the town has so much less than it did when it was 1,200 people. It lost the hospital. It lost transit service to the city, which I used as a university student in the ’50s. Now it has even lost the car dealerships. There were three or four in my day.”

Overall, though, for most of those I spoke with, the positive outweighs the negative. There is a sense of pride and optimism, even excitement, about the future in the now not-so-little town whose motto is “A people place, a change of pace.”

Lynda Buffett

Real estate agent and co-chair of the Heritage Music Festival

Lynda Buffett, real estate agent and co-chair of the heritage music festival. “It used to be that the downtown was struggling, but right now it’s doing quite well. That’s a big plus from having more people moving into town.” Photo by Rosemary Hasner / Black Dog Creative Arts.

Lynda Buffett is a familiar face to many in Shelburne. The longtime resident of a heritage home in the old part of town and one-time mayoral candidate has long been involved in community initiatives.

As a local realtor, she follows both the residential and commercial markets, and sees lots of positives to the town’s burgeoning population.

Recently quite a few downtown commercial buildings have changed hands and the new owners are expressing interest in improving their properties. “It used to be that the downtown was struggling,” Buffett says, “but right now it’s doing quite well. That’s a big plus from having more people moving into town.”

Some owners have added more residential units above the commercial space. “That’s important because these days you can’t rent an apartment anywhere, not just in Shelburne,” says Buffett. New restaurants are starting to bring nightlife to the main street and that too she applauds as an improvement. “It used to be everybody rolled up the sidewalks at 6 o’clock.”

From a residential perspective, Buffett believes the new development has improved the local housing options. “Some people are move-up buyers from older Shelburne to newer and they’re able to stay in their community.”

Another plus: “The newer homes have certainly helped push up the pre-existing market. However, new homes tend to go up in price faster because they’re in bigger demand.” But the quality of the older homes has improved too. “Twenty years ago a lot of them were in really rough shape. Now it’s very seldom you see one like that.”

One shortcoming is a lack of small units. “There are folks who want to retire, and want to downsize, and that’s not something we have here.”

Following suit with the GTA, Shelburne’s real estate market has shifted over the past summer. “Even as recently as last spring, at any given time there might be 10 or 12 houses on the market in town, and things were selling like crazy,” Buffett says. “But right now we’ve got about 50 houses. The normal is between 36 and 40. Everybody is listing because they think prices are going to go way down, but I don’t think that will happen. It’s just we’re not going up at the pace we were.”

Buffett is also co-chair of the Heritage Music Festival, launched in 2016. The event is a rebranding of the fiddle festival. Though the core of the fiddlefest remains, the revamped event aims to offer a broader array of music that, as she says, “attracts all types of people, not just a certain segment.” This year’s headliner was roots-country star Corb Lund.

With its second year of the new program just wrapped up, things look promising. “The results were fantastic,” Buffett says. “Both financial and buy-in from the community. Attendance went way up.”

Perhaps more important, the event drew newcomers. “We’re starting to get a transition, so it’s not just the same old people who have been here forever.”

Pat Hamilton

The high school principal

Pat Hamilton, the high school principal. “You don’t realize how isolated you can be until you start talking to people and find out why they’re here, what their experiences have been.” Photo by Rosemary Hasner / Black Dog Creative Arts.

Pat Hamilton is an upbeat, practical guy born and raised in Dufferin. This fall he takes up the post of principal at Orangeville District Secondary School, where he was once a student. But from 2011 to last spring, he was principal at Centre Dufferin District High School in Shelburne, and last year he was named one of Canada’s top 40 principals by The Learning Partnership, a national charity that promotes public education.

Though the town’s elementary school population has increased along with Shelburne’s dramatic growth, the bulge has not yet hit the high school. People tend to move when their kids are still young, explains Hamilton. What has changed rapidly is the diversity of the student body. “I don’t have statistics, but I’d bet if Shelburne’s population grew 40 per cent, the school’s level of diversity increased by almost as much.”

The new students have backgrounds from all over the world, including the Caribbean, East Asia, Africa and Eastern Europe. There is also a large group of First Nations and Métis youth – in fact, the school has one of the largest Indigenous populations in the Upper Grand District School Board.

Regardless, says Hamilton, “Compared to when I went to high school, these kids are way more tolerant than we ever were. Whether it’s sexual orientation or being transgender – we have four or five transgender kids. We have FNMI [First Nations, Métis, Inuit] kids, we have visible minorities. In my day that would have been a recipe for a lot of tension.”

He acknowledges some people are quick to blame the newcomers for any problems that do arise. But with his long perspective, he says, “You get fights in a high school, you get conflict, you get bullies. That’s what happens when you put a thousand teenagers in one place. You can’t ignore when there is a race issue, but don’t call everything that. For example, a conflict might be about two boyfriends and a girl. Who cares what they look like – that’s what it’s about. It’s normal, everyday tension.”

Hamilton realized early on that approaching the school’s changing demographic as though it were a problem that needed solving was not a useful perspective. “This is not a sickness you need to get a shot for. This is who we are. This is who our community is.”

Hamilton was intrigued when some new students told him about a nonprofit youth mentorship and leadership program called One Voice One Team, run by former CFL football player Orlando Bowen.

In 2004, two Toronto police officers framed Bowen for drug possession, and beat him so badly it ended his career. Later one of the officers was charged with drug trafficking, and all charges against Bowen were withdrawn. The experience inspired him to start One Voice One Team.

Hamilton says working with Bowen changed everything. “We decided we weren’t going to focus on how we’re all different, but on what kind of community we want to build.”

He emphasizes the benefits of a diverse student population. “It’s incredible, their knowledge about the world, the way they see issues, it brings a whole other perspective to discussions in classrooms.”

What’s more, he says, discussions with parents from a wide range of backgrounds has him see the world very differently too. “You don’t realize how isolated you can be until you start talking to people and find out why they’re here, what their experiences have been.”

Alton Stephenson

The newcomer

Alton Stephenson, the newcomer with his son Hayden, 10, at Glenbrook Elementary School. “I like the community, and I’m going to stay. I want to give back.”

Alton Stephenson doesn’t have time to sit down for an interview, so he multitasks, making supper. It looks delicious. It’s a meal he must have made many times – his hands fly while he focuses on our conversation.

Stephenson moved from Brampton with his wife Alethia and two kids to a swank new house in Shelburne four years ago. He and Alethia commute, separately, to their jobs in Mississauga, about an hour each way.

Their 16-year-old daughter Amoy, a ballet dancer who has performed at the Pan-American Games and the Paralympics, still attends school in Brampton to pursue her dance training. Their 10-year-old son Hayden attends the local Glenbrook Elementary School.

Not long after arriving, Stephenson started a drop-in basketball program at Glenbrook. Open to all younger kids in the area, it runs regularly on two weeknights and now attracts about 30 kids. On Saturdays, he runs a similar program for high school students. “Some fathers come out to shoot some hoops too, and hang out with their kids.”

Last year he also started coaching for the Orangeville Hawks basketball team. And he volunteers at his daughter’s dance school. He is, as he says, “busy seven days a week.”

What’s behind it all? “I like the community, and I’m going to stay for quite a few years. I want to give back.”

He’s doing his part, but would like to see more activities available for young people, noting that kids tend to graduate and leave because “there’s nothing for them here. We’ve already seen stories in the newspaper about kids and drugs up here. People think it’s kids from Brampton doing that, but that’s not it at all. People bring their kids up here when they’re small to get them away from that before it starts.”

And it’s worse for girls, he adds. “In the city they can do dancing, swimming, gymnastics, all that kind of stuff. Here they mostly have to go to Orangeville.”

He also has other quibbles with the town: the lack of GO transit and the smell that sometimes wafts from the sewage treatment plant. “We would like to sleep with the windows open at night instead of air conditioning, but the stench is enormous.”

Still, Stephenson remains upbeat. “We don’t have problems; we just have growing pains.” And he’s happy to see his new neighbourhood jelling. People help each other build decks and fences, and there are gatherings that stretch late into the evening. Many of the newcomers are from Brampton, some of them moved up together. “There are a few guys who drive for Brampton Transit,” he says, “and a couple who drive for GO Transit.”

He dismisses the notion that people move to Shelburne solely for cheaper housing. “Brampton got too saturated,” he says. “There are too many people. There’s no place to breathe. I grew up in a Metro Housing neighbourhood. I’ve always been around a lot of people and I just wanted to get away from it all.”

Helen Fleming

The longtime business owner

Helen Fleming, the longtime business owner. “… people speak to me and call me by name wherever I go.” Photo by Rosemary Hasner / Black Dog Creative Arts.

Helen Fleming has some deep roots in Shelburne’s business community. Not only has she owned Pete’s Deli (formerly Pete’s Donuts) at the corner of Highway 89 and County Road 124 for the past 23 years, she’s also been active in the chamber of commerce and served on the board of MADD Dufferin. Her husband Bruce, now retired, was the third generation to own Fleming Dominion Hardware in town.

But Fleming is stepping back from the business this fall. “I was going to retire when I was 55, then 60, then 65, then 70, and I’m past all those,” she says. “But I love the people, I love that contact. That will be the hardest part for me.”

Pete’s is Shelburne’s modern-day version of the hometown coffee shop that has long existed in small towns across the country. With way more character than the chain alternatives, it’s a boisterous, jovial place where the food is dependable and the faces are familiar. The bagels are piled high with cream cheese or other savoury temptations, and the sausage rolls are second to none. A large coffee with a muffin will set you back about $3.60.

While Fleming will continue to manage the paperwork from home, the restaurant will be run by what she describes as her “excellent” staff. She brought them on board with the proviso, “If you can’t find a little joke and some humour in a day, go find a job somewhere else.”

Fleming is pragmatic about the town’s growth. “It’s good news and bad news. When it was a tiny town, 23 years ago, you knew everybody who walked in the door and it was a slower pace,” she says, “On Fridays now, I take the back lanes to get around town. I don’t want to take Main Street because I know how clogged it’s going to be.”

She also feels the town needs to step up to the plate when it comes to amenities. “The growth is going to require a lot of money that I’m not sure the town is prepared to pay, because residents are going to demand more things.”

However, she adds, although there were some initial challenges, the town’s expansion population has been good for her business. “Two years before Tim Hortons’ arrival, I decided to take donuts right out of the lineup. Still, I lost a lot of business when Tim Hortons first came in.” Gradually, though, the added population began to take up the slack.

Of the pace of growth, she says “No, I don’t think it has been too fast. I think it has been a long time coming. And I don’t see a detriment to the increased population. I see it as a positive thing.”

True to her engaging nature, when asked if she has begun to develop relationships with the newcomers, Fleming says, “Apparently I have, because people speak to me and call me by name wherever I go.”

Bob Currie, Wallace Elgie & Bill Bentley

The coffee klatsch

![From left : Bob Currie, Wallace Elgie and Bill Bentley, with Al Widbur, also a Pete’s regular. “The thing is, there’s nothing you can do about [ Shelburne’s growth ]. You can’t stop it. All you can do is try to plan for it and manage it.” Photo by Rosemary Hasner / Black Dog Creative Arts.](https://www.inthehills.ca/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/Shelburne_CoffeeKlatch21.jpg)

From left : Bob Currie, Wallace Elgie and Bill Bentley, with Al Widbur, also a Pete’s regular. “The thing is, there’s nothing you can do about [ Shelburne’s growth ]. You can’t stop it. All you can do is try to plan for it and manage it.” Photo by Rosemary Hasner / Black Dog Creative Arts.

Humorist Dan Needles launched the prototype for his hugely popular Wingfield Farm series of plays in the 1970s when he was editor of the Shelburne Free Press and Economist. The plays, which put Shelburne on the map as Larkspur, grew out of a column he wrote to fill space in the paper.

As Needles, now a columnist with this magazine, recounted in a 1995 profile, “There wasn’t a whole lot of news in Shelburne. There were 26 issues that were warm-up fiddle contest issues, and there were 26 wrap-up issues. The crossover was sometime in February.

“I used to go across the street to the Gulf station after the paper came out and I’d hand my paper to the guys and sit on the Coke cooler while they’d read it in about 30 seconds. And they’d say, ‘Well, that was a great effort, Dan, but now we’ll tell you what really happened,’ and you couldn’t print any of it. There was lots happening, but it was all Local-Minister-Runs-Off-with-Organist stuff that you couldn’t parlay into a straight news story.”

For a couple of decades now, Pete’s Deli has taken over as the meeting place for a group of old-timers who drink coffee, chew the fat and tell stories that will never make it to print. As owner Helen Fleming good-naturedly quips, “They get here at three, and they stay … forever.”

On this day Wallace Elgie, aged 91, sits with Bill Bentley, who chooses not to reveal his age. Elgie has spent his whole life around Shelburne and says he can remember when the population was 1,300. Bentley has spent most of his life here too. Both are still on their farms.

They’re joined by Bob Currie. Currie is the newcomer in the bunch – he has been in the area only 53 years. He’s still on his farm too, though he also had careers as a real estate agent and longtime politician and mayor of Amaranth Township. As those who know him would attest, he’s rarely caught without an opinion, or the willingness to express it.

One thing that isn’t like it used to be decades ago in Dufferin: farmer fashion. At least, to this farm boy’s eye. The peaked caps are still de rigueur, but these guys are sporting some serious going-to-town-on-Saturday-night attire, with button-down shirts in tasteful check patterns. There isn’t a pair of green farmer pants or a manure-covered rubber boot to be seen.

Confronted by some fool journalist, Elgie and Bentley defer to their media-savvy companion.

About Shelburne’s growth, Currie says, “The thing is, there’s nothing you can do about it. You can’t stop it. All you can do is try to plan for it and manage it.” Overall, he sees Shelburne’s development as a positive thing, pointing to the expanding commercial sector and big employer KTH Shelburne Manufacturing.

Like dozens of businesses in the region, KTH supplies Alliston’s Honda plant, which itself employs about 4,600 people. And it’s on this point Currie offers up a scenario that makes folks lean in. There have been efforts to establish a union at Honda for several years. Speculating on what the company’s response might be should that take place, he paints a picture reminiscent of the cancellation of the Avro Arrow in 1959 and the devastating impact that had on local employment. “Imagine what would happen to this area if Honda pulled out. Thousands and thousands of people would be out of work.”

Sanjay Lekhi

The pharmacist

Sanjay Lekhi, the pharmacist. “Because I had already worked in Shelburne, I knew this was where I wanted to be. The people are really nice and friendly, and they already know I have the skills and expertise.” Photo by Rosemary Hasner / Black Dog Creative Arts.

Sanjay Lekhi did his homework before opening a business in Shelburne. After emigrating from India in 2000 and fresh from obtaining his pharmacist’s licence in 2004, he spent four years working at the town’s No Frills supermarket pharmacy. In 2007 he was recognized as Pharmacist of the Year in the Loblaws Zone Eight region – an accolade determined by confidential customer reviews.

For two years after that, Lekhi says, “I wanted to explore what other communities are out there, so I did locum work all over southwestern Ontario, and a little bit up north.” The next step was a three-year stint as owner of Shoppers Drug Mart in Fergus.

However, Lekhi says, “I always wanted to start my own family business – that was the goal. Because I had already worked in Shelburne, I knew this was where I wanted to be. The people are really nice and friendly, and they already knew I have the skills and expertise.” He adds that the rapid population growth was also a big factor in his choice of location.

So in 2013 he and his wife Shalini opened Shelburne Town Pharmacy in a busy plaza that also houses Foodland and Giant Tiger. They commute there from their home in Orangeville.

Over a busy 15 minutes in the store, it’s clear this is a bustling hub where it seems everyone is on a friendly, first-name basis, or even more casual. Without introduction, a tall teenager passes Shalini a prescription, saying nothing more than, “Mom will be in to pay for it.” She smiles and nods, then sets about filling it.

“Customer service is in our hearts,” Lekhi says, “so that’s why it’s not difficult to remember a person’s name.” Of his diverse clientele, he adds, “As a human being, every person would like to be treated with respect and cheerfulness – I think that’s the bottom line.”

It would seem to be a winning strategy. Lekhi says that so far, “It has worked out much better than expected. We probably have thousands of patients now, and we started from zero. So to get to this point is a big deal.”

Another significant focus is community involvement. Three years ago Lekhi started an annual fundraiser for Sick Kids hospital, held the Saturday after Victoria Day at the store. This year’s edition raised about $4,900. Last spring he also opened a telemedicine walk-in clinic in a space behind the pharmacy. A registered nurse is onsite weekdays, and patients consult with doctors via video link to an organization called Good Doctors, located in Sudbury. Lekhi covers the cost of rent and overhead.

Of all the effort it has taken to build his successful business, Lekhi says, “You definitely have to work hard when you’re an immigrant.”

Jeff Rollings is a freelance writer and planning technologist who served as a consultant to Shelburne’s Economic Development Committee from 1999 to 2007. A town marketing package he produced won two awards from the Economic Developers Council of Ontario in 2001. His story about designing the town’s logo with artist Laurie McGaw appeared in the autumn 2007 issue of this magazine.

Related Stories

Once a Village

Jun 21, 2017 | | HeritageThe 19th century saw tiny villages spring up all over these hills, bearing sturdy names like Lockton and Elder, unusual names like Biggles and Shrigley, and pretty names like Camilla and Silver Creek. They faded away, but left a legacy that helped create the hills we know today.

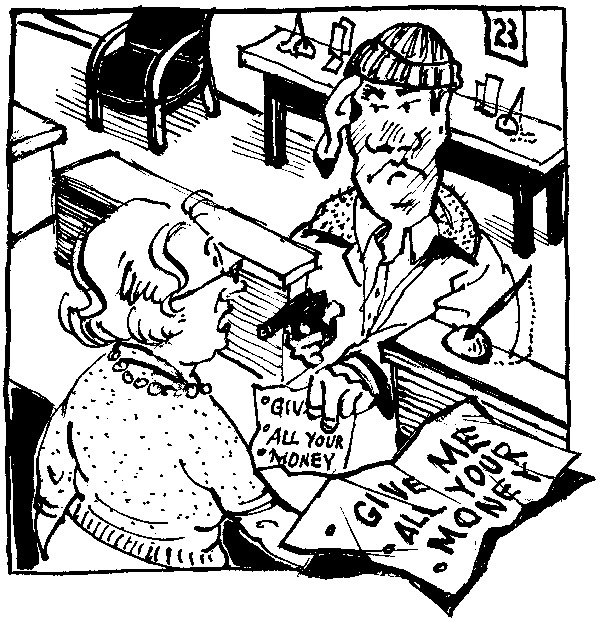

How Not to Rob a Bank: Shelburne’s First-ever Bank Robbery!

Mar 21, 2009 | | Historic HillsShelburne’s first-ever bank robbery began as a pretty scary affair, but in the hands of a bumbling stickup man it ended more like a gong show.

Finding Balance in Caledon: The Urban/Rural Divide

Jun 16, 2015 | | EnvironmentIn less than two decades Caledon’s population will be 75 per cent urban. Can its countryside values survive the shift?

Places to Grow turns 10

Jun 16, 2015 | | EnvironmentThe Growth Plan was an attempt to rein in the low-density sprawl that was a signature of development in the 1980s and 1990s.