Dancing in the Dark

From dusk until dawn, our local bats perform an aerial ballet, devouring millions of flying insects.

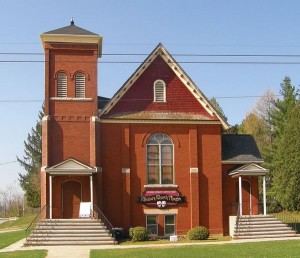

Bats in the belfry: Come dusk in the summertime, hundreds of bats stream out of Century Church Theatre in Hillsburgh.

On sultry summer evenings, patrons of the Century Church Theatre in Hillsburgh can enjoy fine drama or comedy and, as an added attraction, take in some nicely choreographed natural theatre as well – hundreds of swooping, swirling bats emerging from the church attic.

“The bats are quite an attraction during our Summer Festival,” says Jo Phenix, president of the Erin Arts Foundation which oversees the theatre. “They fly out just about intermission time, so the audience can go outside and watch them.” Dusk is their cue and the airspace over Hillsburgh’s ponds, woods and backyards their stage.

Phenix’s husband, actor and director Neville Worsnop, laments that for the 2006 production of Dracula, “We had to construct our own bats, and rig lines to fly them through the audience, because we couldn’t train the real things to fly on cue.” (Bats are splendid aerial performers but they don’t take direction very well.)

The denizens of Century Theatre are little brown bats, one of the most common species in Ontario. Along with their larger cousins, the big brown bats, they are the ones that most enjoy the warm, cozy accommodations so graciously provided in the homes, barns and churches throughout the Headwaters region.

Their local population numbers in the many thousands. And though they may not be the prettiest creatures on this green earth, they are certainly among the most unusual, and it’s hard not to love an animal that can consume as many as 600 mosquitoes an hour!

To be fair, that impressive number of mosquitoes was counted by scientists in laboratory conditions, where the bats were offered nothing but mosquitoes. With the night skies full of moths, caddis flies, mayflies and June bugs, mosquitoes might be on the bats’ menu, but as the appetizer not the entrée. A bat overflying a summer barbecue might witness a similar feeding strategy among human diners, who start with shrimp, but gravitate to steak or cheeseburgers.

A little brown bat – one of four bat species in Ontario commonly referred to as LBJs, or “little brown jobs.” Photo By Brock Fenton.

Our local little brown males heartily consume half their body weight every night. The females – at least nursing ones – are pure eating machines, each one consuming a mass of insects in excess of her body weight nightly.

In Hillsburgh, by the time the slanted rays of dawn strike the steeple of Century Church on a summer morn, hundreds of thousands of insects have disappeared down the gullets of the resident bats.

Bats hunt with their astonishing echolocating ability, sending out pulses of sound and then “reading” the returning echoes for the shape signatures of potential prey. So finely tuned is this ability that a bat can distinguish between different species of insects in complete darkness. They often eat while flying, using their wings or tail membranes to scoop insects into their mouths in a gustatory aerial ballet.

Four of the eight bat species that hunt insects in the Ontario night are LBJ’s or “little brown jobs,” look-alikes to anyone not versed in the subtleties of bat identification – which means just about all of us.

The other four species are more distinctive. Big brown bats resemble the LBJ’s but are noticeably larger. Red bats are – not surprisingly – red and, believe it or not, rather cute. Silver-haired bats are frosted with silver-hairs. Hoary bats are the big daddies of our bat fauna, with individuals weighing as much as five little brown bats.

Reds, silver-haireds and hoarys are migratory, travelling north or south with the birds according to the season. These three species are forest dwellers and, unlike little and big browns that enjoy crowded company, they usually hang alone from branches or, in the case of silver-haired bats, under bark or in woodpecker holes.

Fiona Reid, a writer and artist from Speyside, Ontario and the author of the recently released Peterson Field Guide to Mammals of North America, painted one of these silver-haired bats for the field guide. She found that it soon became gentle and trusting. It quickly warmed up to her and would beg incessantly for mealworms, easily handling fifty of those beetle larvae at one sitting.

“I got fed up after a while having to constantly feed it,” she says. And the bat? “Well the bat got really chubby.”

In spite of their gluttony, Fiona Reid loves bats. “They are beautiful, charming and amazingly well adapted to their environment,” she says.

Last summer Reid did a bat inventory for Credit Valley Conservation. Using high-tech equipment she recorded the ultrasonic chatter of bats flying throughout the Credit Valley Watershed. It turned out that the watershed is generously endowed with Ontario bats, with seven species coursing its skies. Caledon Lake was a hotspot, with the full complement of Credit Valley Watershed species flying there.

Bats face a precarious future. Those that overwinter in Ontario, including little brown bats and big brown bats, are particularly vulnerable to disturbance of their hibernation sites. These bats often travel hundreds of kilometres in the fall to find the perfect conditions for outlasting our long, cold winters. Such sites are usually caves or abandoned mines.

They enter these winter refuges with finite energy reserves, their next meal months away, and this can prove their undoing. If roused even once from winter slumber, by human intruders, a little brown bat can lose sixty days worth of energy as it ramps up its metabolism to avoid the perceived threat. Starvation prior to spring is the likely outcome.

Fiona Reid has noted bat declines and disappearances from Niagara Escarpment crevices due to human disturbance. “There needs to be a greater effort here in Ontario to find out where the bats are roosting and to keep people out, at least on a seasonal basis,” she says. Reid is quick to add that serious cavers are usually quite receptive to bat conservation initiatives, and that it is casual thrill seekers who often cause the harm.

While the disturbance of hibernation sites has long threatened bats, new ominous threats have arisen in recent years. One is a virulent disease called White Nose Syndrome that is currently killing huge numbers of bats at hibernation roosts just across the border in New York State.

The white fungus growing around the noses of the infected bats is believed to be a secondary symptom of an unknown pathogen that may be fungal in nature but could also be a virus, bacteria or toxin. What is known is that this new-found disease is as lethal to bats as the Ebola virus is to people. Merlin Tuttle, the president of Bat Conservation International, told the New York Times last March that “this may be the most serious threat to North American bats we’ve experienced in recorded history.”

As yet, White Nose Syndrome has not been found at Canadian hibernation sites, but it is likely only a matter of time before it will. Like birds and monarch butterflies we share “our” bats with our southern neighbours. There seems real potential that white nose disease may destroy a large percentage of our bats – a boon for moths, mosquitoes and bat-phobic people, but a disaster for the environment.

Another new and serious threat to bat survival is the proliferation of wind turbines on the landscape. It appears that the hum of a turbine’s spinning rotors, while music to the ears of humans seeking clean energy, is a siren sound for many of our bats. Bats seem inordinately attracted to wind turbines for reasons not fully understood. What is clear is that unless answers to bat mortality at wind turbine sites are found, we are going to lose a lot of bats.

Thomas C. Erdman of the University of Wisconsin has studied the problem and offers some preliminary insights. He thinks that bats are dying not from hitting the rotor blades, but from the 200 km/hour turbulence the spinning blades create, and that this turbulence drives the bats into the ground. Further, he believes that some bats may survive the fall but then can’t become airborne again because, in the agricultural fields where most wind turbines are located, there are no trees or shrubs available for the bats to climb up on and launch themselves into the air.

A study released last year by University of Calgary researchers indicated that “bat fatalities increased exponentially with tower height.” They found that turbines with towers higher than 65 metres were particularly deadly.

This finding has relevance for the Melancthon wind power project in Dufferin County where the forty-five towers top out at 80 metres.

In 2007, Canadian Hydro counted dead bats at its Melancthon I turbines during the spring and fall migration periods. Mortality rates for a four-week period in the spring were estimated at 0.2 bats per turbine, and for an eight-week period in the fall at 4.2 bats per turbine.

Thomas C. Erdman suggests the higher death toll in the fall occurs because the larger number of insects in agricultural fields at that time is attracting feeding bats. Bats, providing free pest control, are being killed.

Thomas C. Erdman suggests the higher death toll in the fall occurs because the larger number of insects in agricultural fields at that time is attracting feeding bats. Bats, providing free pest control, are being killed.

If the Canadian Hydro mortality rates are accurate, they suggest that about 200 bats met their demise at the existing towers last year. If this rate holds for the additional 88 turbines coming on line in Melancthon II, just under 600 bats may be killed by all 133 turbines per year during spring and fall migration.

Worse, the actual death toll may be considerably higher. Fiona Reid says that “all the estimates of mortality will be underestimates because the bat carcasses will be quickly scavenged by predators like raccoons.”

Other factors also make it difficult to calculate the actual death toll. Bats driven to the ground by turbulence will likely be scattered over a wide area and hidden in vegetation.

Consider as well that the Melancthon wind farms are not the only wind turbine sites that our wide-ranging bats encounter on their migratory flights. For example, some of the red bats that spend the summer in Ontario fly a gauntlet of wind turbines along the Appalachian Mountains to get here. And the existing wind turbines are just a prelude to what is apt to be a tremendous expansion of that mode of power. We may be prepared to sacrifice bats for clean energy, but surely it is in everyone’s interest to find ways to mitigate the slaughter.

The Century Church bats, in fact bats everywhere, merit our respect. They have worked very hard to earn it. And now, more than ever, they need our help. We need to find creative ways to co-exist with them and, more than that, to enhance their life chances. A summer’s night bereft of bats would be a night diminished in wonder and magic.

More Info

Do bats carry disease?

Fears are exaggerated, but be cautious

Bats in buildings tend to be notoriously unwelcome. That’s due in part to fears that they carry disease, particularly rabies.

Bats can carry rabies, as can foxes, skunks, raccoons and many other wild mammals. However, death from rabies in this country is exceedingly rare. The Public Health Agency of Canada reports that over ninety years, from 1924 to 2oo4, only twenty-three people died from rabies in Canada, contracted from a variety of mammals, not only bats.

Further, rabid bats do not become aggressive, as many other mammals do. They do not, as the horror flicks would have us believe, descend maniacally from the sky to bite the flesh of exposed necks. The few people who have been bitten by a rabid bat have typically picked up a bat flopping about in its death throes on the ground. Obviously, wild animals, particularly those acting strangely should not be handled.

If fear of rabid bats is largely unfounded, so too is the fear of histoplasmosis, a fungal disease sometimes present in the feces of birds and bats. It can cause flu-like symptoms and, in people with immune deficiency problems, can be more dangerous.

In some southern caves where people spend considerable time digging guano for fertilizer, bat histoplasmosis can be a problem. I am not aware of any studies of bat histoplasmosis in Canada, but Brock Fenton of the University of Western Ontario writes in his book, Bats, that, “In New England a survey of guano accumulations in several colonies of big brown bats and little brown bats produced no evidence of histoplasmosis.”

Nevertheless, most of us are not keen on the idea of bat guano, or bat “poop,” accumulating in our attics. I put this concern to Crystal Schintz, a transplanted Canadian who now works as Helpline Officer for Bat Conservation Trust in the U.K. She responded that since British bats (and ours) feed exclusively on insects “their droppings are very dry and usually don’t cause any offensive odours. The droppings will crumble to dust, as they consist only of indigestible insect parts. They can be swept or vacuumed up and the droppings make an excellent fertilizer for the garden.”

So there you have it. You can use your bat droppings to grow bigger tomatoes! However, because of the slight chance of histoplasmosis in Canadian bat guano, do use prudence in removing it from your attic and wear a proper face mask.

In Britain where Crystal Schintz works her bat helpline, bats are so highly valued that British law offers full protection to those that roost in public buildings. And while it is possible to evict bats from private residences in England, it is against the law to do so without the consultation and involvement of wildlife officials who will first try to convince the property owner to live and let live.

Joan Donnelly is one Headwaters resident who embraces this live-and-let-live philosophy. She has watched little brown bats fly from the attic of her Caledon farmhouse for most of the last sixty-five years. Donnelly remembers that these bats were not a big deal for her parents. They were accepted, not feared. Perhaps not coincidently, Donnelly ended up studying bats at university.

If your house has gone “batty” and if you do not embrace Joan Donnelly’s enthusiasm for co-existence, if you simply can’t bear the thought of guano in the attic, the only humane and effective way to see them off is by exclusion.

That means plugging up all of the cracks, crevices and holes that allow bats to gain access to your house. Such a project should not be done during the warm months when you could end up separating mothers from their babies, causing their deaths.

Little brown bats vacate our attics before the snow flies, so the best time to conduct your exclusion project is from late fall to early spring.

The tiniest openings will need to be covered because, incredibly, little brown bats can wriggle through even dime-sized holes. Occasionally big brown bats will occupy dwellings year-round. Excluding these bats is somewhat more complicated.

Joan Donnelly now offers her bats a choice of accommodation. With her husband, Gerry, she has put up five bat houses on her farm buildings. Bats make good use of these from spring to fall.

To enhance their bat appeal, bat boxes should be painted black and placed high on a south or southeast facing wall to capture as much sunlight during the day as possible. Bats like it hot.