Natural Enemies: Horse vs Automobile

Just over a century ago the horseless carriage chugged into these rural hills and ran head on into a horse-reliant culture. What began as a novelty soon became a nuisance, sparking a battle for supremacy on the roads.

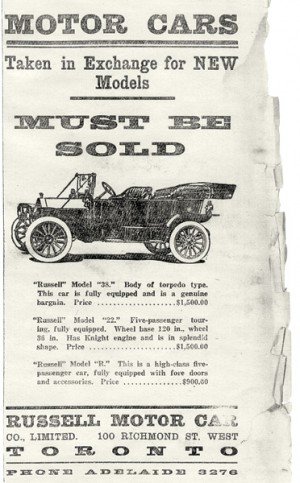

This ad appeared in The Shelburne Economist in 1914. The Russell Motor Car was a popular and reliable Canadian auto. A subsidiary of CCM, Russell converted to war production in 1915 and after the war sold out to Willys-Overland in the U.S. Photo Courtesy Dufferin County Museum And Archives.

From late spring to early fall, when Mrs. Angus Thomas harnessed her little white mare at the family farm on the 5th Line of Erin Township, she rarely went farther than nearby Marsville or occasionally to Orton. In winter though, Mrs. Thomas didn’t think twice about going as far as Erin or, if the weather was pleasant, all the way to Orangeville.

The difference? In winter there were none of those dreadful automobiles on the roads to frighten her mare.

On a day in late July 1909, however, she had to take a family visitor down the Guelph Road to Ospringe, and the inevitable happened. An auto suddenly appeared over a hill and the little mare bolted, overturning the buggy and injuring Mrs. Thomas so critically she might have died had not the auto driver (no one drove a “car” for another ten years or so) raced into Erin for a doctor.

Had she followed the “Instructions for Ladies” published in local papers at the time, Mrs. Thomas might have avoided this accident.

“When an auto is in sight,” the Shelburne Economist advised as early as June 13, 1907, “run your horse into a fence corner, and if it is a rail fence, pull it down and get into the field. If, because of ditches, this is found impossible, provide yourself with two large handkerchiefs. Tie one over the eyes of your horse and the other over its nose; then it will neither see nor smell.”

There is no evidence that anyone ever avoided disaster by following those impractical recommendations, but the publication of such desperate advice was a measure of how serious the problem was a century ago. On the roads of our hills in those early days, cars and horses were a volatile mix.

A widespread conflict

Several decades earlier, the railroads had also had an impact on the safety of horses and other livestock, but the benefits of rail transport were so universal that drawbacks to the Iron Horse were quickly forgiven and accepted. Besides, the railways brought few surprises. There weren’t many tracks and the trains’ arrivals, for the most part, were scheduled. Not so for the auto. Not only was it considered an impractical toy, it could appear unexpectedly anywhere and any time.

When Orangeville’s favourite “fruit man,” Mr. Scott of Melville, ended up with his strawberry delivery scattered all over Broadway because an auto had frightened his horse, the suddenly strawberry-deprived citizens of Orangeville were understandably irate.

Some miles away in Bolton, an Albion farmer, Wes Lockhart, had even greater cause to be angry about automobiles. The driver happened to motor down the south hill just as Wes was driving his horse into town from the north. Wes ended up in a Toronto hospital with both legs fractured after the horse tried to take him and the buggy to safety – over a fence.

Still, it was in the country where the battle was keenest. In May, 1914, Mulmur Township logged almost a dozen runaway horses as autos came off the blocks for the motoring season. Mono and Caledon totted up similar numbers.

On one spring night, just west of Grand Valley near Peepabun, John Simes’ team took fright at the sight of an auto and dumped him, and Robert Dixon hit a cow with his Ford runabout. Those were typical meetings of auto and livestock at the time, but some accidents were more serious, even fatal.

In late June of 1910, for instance, a Melancthon farmer named Marshall was unloading gravel when Dr. Cowan of Horning’s Mills approached him in his Russell Light Six touring car. The doctor had been warned that Marshall’s horses were skittish and he stopped well away from them and, as required by statute, sounded his horn before approaching. Unfortunately the horses panicked and Marshall was killed.

At the conclusion of the lawsuit that followed, a local jury awarded the Marshall family significant damages. Word leaked out later that some members of the jury had argued for an even greater award to demonstrate to “autoists” that they were not welcome on rural roads.

Not always the horses’ fault

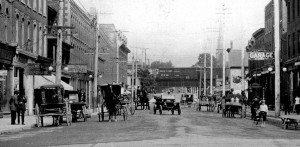

In the early twentieth century, a lone auto driver navigates among the carriages on Brampton’s Main Street. Photo Courtesy Region Of Peel Archives.

Although testimony in Dr. Cowan’s litigation suggests he was an able driver and followed both regulations and common sense, many drivers could boast no such competence.

Controlling an ‘automobile’ (from the Greek autos [self] and the Latin mobilis [moving]) called for an understanding of physics that was brand new.

A dramatic case appeared in a wire-service story picked up by the Bolton Enterprise. It described a Saskatchewan farmer who pulled desperately on the steering wheel and shouted “Whoaaa!” as he plunged into a neighbour’s greenhouse.

Early auto engineering didn’t help either. To stop the brakeless LeRoy, for example, a one-cylinder model manufactured in Kitchener, the driver had to shift into reverse.

Steering at the unfamiliar speeds was also not an easy skill to master, especially on unbanked roads. As a consequence, the majority of accidents that did not involve horses were single-vehicle types. A six-cylinder Keeton (manufactured in Brantford) illustrated the problem one day in 1914 on the 2nd Line of Amaranth when the driver tried to turn on to the Town Line without slowing down. He ended up re-plowing much of an adjacent field.

On the same day in Cheltenham, Hugh Drummond boarded three lady passengers, set the dash levers and went out front to crank-start his vehicle. The engine turned over and the auto took off – backwards. The three women were unharmed but spent much of the afternoon in the car, upside down in a ditch! Such incidents did little to convince horse-fanciers that matters might improve one day.

Achieving peace & accommodation

Dufferin native W.J. (Jack) Hughes shows off his Model T Ford, c. 1926. In perhaps one of the earliest efforts at mobile advertising, the manufacturer of cornflower glass had a cornflower etched into his auto’s rear window. Photo Courtesy Dufferin County Museum And Archives.

However, matters did improve – though not easily nor speedily. Farmers throughout these hills were notorious for attempting to discourage auto drivers by laying studded planks across rural roads, or even barbed wire and upturned saw blades. A popular trick was to uproot road signs put up by the new associations (motor leagues) that sprang up to assist drivers who simply wanted to go motoring in the country.

Such guerilla activity was self-defeating, however, and short-lived. Especially because farmers themselves became autoists as cars became more affordable. (In 1917, at Brett & Thompson in Shelburne, a new Ford Runabout sold for just $475.)

Even more important, as the Shelburne Free Press put it, “protest against automobiles being allowed to use country roads is heard less frequently, partly because horses are becoming used to these machines, and partly because the auto is rapidly winning its way into general use by agriculturalists.”

When the Free Press devoted much of a full page to an enthusiastic description of the Dufferin Farmers’ 1916 Automobile Tour – some forty farmers on a one-day fact-finding and information tour from The Maples all the way to Guelph – it was clear that the battle for the roads in these hills was over. The former nuisance had become a convenience.