Medicinal Wonders?

“Why Die a Lingering Death of Direful Diabetes? Dodd’s Kidney Pills Cure It!”

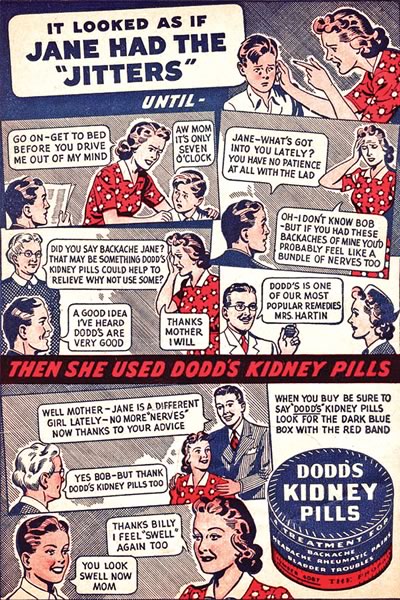

The McKee family from Rosemont bought the Canadian rights to Dodd’s Kidney Pills around 1900. Dodd’s Kidney Pills outlasted the vast majority of “patents,” an indication of the likelihood of some beneficial effects. This ad was one of a series published in the 1940s.

There was a time here in the hills when powerful advertising made every family feel insecure without a shelf full of “patent medicines” – the pills and tonics and balms and syrups that promised a cure for every condition. Fortunately for the readers who missed out on Zam-Buk, the Enterprise had something else to make them feel better. It was a news item about a woman who had rushed to keep her husband from committing suicide with a razor, only to realize he was trimming his corns. She saved him from life-threatening bloodshed with Putnam’s Painless Corn Extractor!

Like most people in the hills, Enterprise readers would have had Putnam’s on their shelves and were likely relieved to think at least some of their money had been spent wisely.

Mixing News and Cures

By presenting the hype for Putnam’s as genuine news, the Enterprise was generating ad revenue in a manner practised by every newspaper of the day.

In a February 1905 issue, for example, the Enterprise offered news about a government proposal to tax fence wire, an item on crop management, and a description of special rail fares for settlers heading for the newly established provinces of Alberta and Saskatchewan. Scattered among these items were large, bold-faced lines declaring: “Minard’s Liniment Cures Diphtheria” and “Minard’s Liniment Cures Distemper.” Then, in the very middle of the page is a letter from one, Chas. F. Tilton, confiding that Minard’s Liniment is such a sure relief for sore throat that he would not be without it, even if a bottle cost one whole dollar!

The April 1897 issue of the Shelburne Economist offers another typical example of the blurred line between advertising and editorial. It ran a column of wire service news: in Germany, Bismarck recovers from illness; in New York, a woman escapes from jail and heads for Canada; in Owen Sound, a woman sues a local minister for breaking up her engagement. Then, barely missing a step, the Economist leads right into: “Why Die a Lingering Death of Direful Diabetes? Dodd’s Kidney Pills Cure It!”

It’s hard to know whether the publishers felt any scruples about their practice – but if they did, they obviously came second to what was clearly a significant source of income. The Economist carried no less than twenty-one “patent medicine” ads in the April ’97 issue, while the somewhat smaller Enterprise that week had fifteen. In Orangeville, an October 1914 issue of the Sun, gave more space to Cubicula Soap (“effective for dandruff, pimples, blackheads and distressing facial eruptions”) and Dr. Hamilton’s Pills (“a wonderful woman’s medicine”) than it did to reporting on the war in Europe.

To a typical newspaper subscriber, promotional strategies like these made the exaggerated claims of patent medicines seem more important than news.

You Got It? We Cure It!

And the claims were certainly exaggerated. At the turn of the twentieth century, The Great South American Nervine Tonic, for example, available at T.F Brown in Shelburne or McEnamey’s store in Cataract – indeed, at any store in these hills – guaranteed a sure cure for “nervous debility, prostration, sleeplessness, headache, hysteria, sexual debility, epilepsy, St. Vitus dance and indigestion.”

And the claims were certainly exaggerated. At the turn of the twentieth century, The Great South American Nervine Tonic, for example, available at T.F Brown in Shelburne or McEnamey’s store in Cataract – indeed, at any store in these hills – guaranteed a sure cure for “nervous debility, prostration, sleeplessness, headache, hysteria, sexual debility, epilepsy, St. Vitus dance and indigestion.”

Paine’s Celery Compound went even further, proclaiming itself the “king of medicines” based on the hundreds of letters it had received from people “truly plucked from the grave” by its marvellous curative properties.

Letters from miraculously cured sufferers were a common device used by the patent medicine makers. Not surprisingly, the majority of the testimonials came from large cities in the USA, but by 1897, Dodd’s Kidney Pills among others was quoting local residents. Fred Stokes of Barrie, for example, is cited in the Shelburne Economist as regaining the forty-five pounds he’d lost from diabetes, after a few boxes of Dodd’s. One box of Dodd’s also started J.K. Nesbitt of Stayner on the road to recovery from diabetes and led to his being “perfectly cured,” while D. Roblin, the bandmaster in Allandale achieved the same result with six boxes.

Some producers wrapped their promotions in “health-help” columns, especially in cases of socially embarrassing diseases. Through the late 1890s, the Orangeville Sun regularly carried an item by Scott’s Emulsion (a processed cod liver oil) in which consumers were encouraged to write Drs. Kennedy and Kergan in Detroit for advice on curing “syphilis, stricture, gleet (gonorrhea), pimples, lost manhood and unnatural discharges.” On the same page in much larger type, Scott’s Emulsion promoted itself as “helpful in consumption,” but its use “must be continuous.”

Did Consumers Really Believe?

In an era when otherwise intelligent adults carried chestnuts to ward off arthritis, peeled moss from tree bark during a full moon to apply to warts, and made poultices from fresh cow manure, it’s not a stretch to think they believed that Dr. Williams’ Pink Pills for Pale People might “cure nervousness, rheumatism and all blood troubles.” (In Canada, the Dr. Williams firm was also the maker of Dead Shot Worm Pellets.)

Nor was medical science of much help. At a time when the Erin Advocate was telling its readers that Cook’s Cotton Root Compound was a “uterine tonic that relieved women’s frailties,” many doctors were still using bleeding and blistering therapies on their patients no matter what the illness. And throughout the height of the patent medicine era, psychiatry was immersed in the theory of phrenology, a concept which held that an individual’s behaviour could be assessed and predicted by the contours of the face and skull.

In 1900, Lister’s theories of antisepsis were barely forty years old and antibiotics were forty years in the future. Little wonder consumers accepted the possibility that Ayers’ Sarsaparilla might heal “sore eyes, sore ears and scrofulous taint.”

In 1900, Lister’s theories of antisepsis were barely forty years old and antibiotics were forty years in the future. Little wonder consumers accepted the possibility that Ayers’ Sarsaparilla might heal “sore eyes, sore ears and scrofulous taint.”

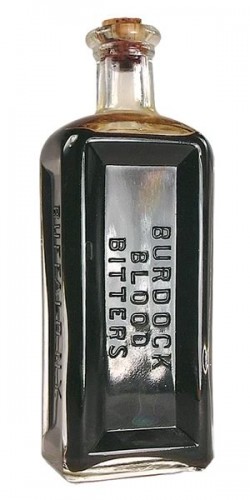

The Era Passes

For the most part, the patent nostrums contained relatively harmless ingredients, and scientists today generally agree that most users who claimed to be cured of cancer, diabetes and tuberculosis were incorrectly self-diagnosed. Also many “patents” were powered up with stimulants like cocaine and grain alcohol. (“Peruna,” a popular tonic during the prohibition era contained 18 per cent alcohol. The original version of Coca Cola, with cocaine, began life as a medicine.) Thus, if nothing else, the user sometimes felt better, if only briefly, an outcome often interpreted as a cure.

In today’s “non-prescription medicines,” as they are called, the stimulants are strongly regulated, and high risk ingredients – such as radioactive uranium added to some “patents” after about 1900 – are long gone.

As for the outrageous claims, they have all but disappeared in the face of improved science and education. Case in point: a 1941 ad for Dodd’s Kidney Pills in the Grand Valley paper urged readers to turn confidently to Dodd’s at the first sign of kidney trouble. The ad noted that the pills were, “for over half a century, the favourite kidney remedy. Easy to take.” Compared to the language of fifty years before, the ad was a model of restraint.

Related Stories

All the News That’s Fit to Print

Mar 21, 2016 | | Historic HillsIn the 19th century a weekly newspaper was the primary source of information, commerce, entertainment, argument and gossip for the people of rural Canada. Few papers did the job better than the Orangeville Sun.

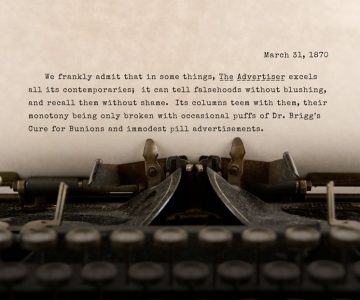

An 1870 Media Battle over “Fake News”

Mar 26, 2018 | | Historic HillsThe tweets and accusations of fake news in today’s media seem almost dainty compared to the Orangeville Sun’s lambasting of its rival weekly, the Orangeville Advertiser.

Hello Victoria

You could try searching for Dr William Buchan’s Domestic Medicine. Extremely popular.

It was published in the 1760s and was still available into the twentieth century.

The other possibility is any of the many free brochures published by patent medicine companies, especially post WWI up to about the 1960s. There are many of these and most regional museums have samples. Maybe a visit to the local museum is on your upcoming travels.

Valerie on Nov 8, 2018 at 8:10 am |

I am 75 and remember my parents getting a booklet in the mail free of charge and full of adds for things like Dodd’s kidney pill etc.. I also remember a chart of the body pointing to other parts indicating interactions, if this hurts it could be because of this. for example if you had heel pain you could have hemorrhoids. This proved true for my mother and me in latter years. Mother often referred to this chart with some success, I would love to have a copy of this chart just because. We received these books in the 50’s. If it is possible to order the chart or a book I would do so. If you could connect me with a source I would greatly appreciate it. Thank you for your time. VICTORIA

VICTORIA HARDING on Oct 26, 2018 at 5:54 pm |