All the News That’s Fit to Print

In the 19th century a weekly newspaper was the primary source of information, commerce, entertainment, argument and gossip for the people of rural Canada. Few papers did the job better than the Orangeville Sun.

On May 20, 1869, a Thursday, it took Matilda Clark three hours to walk to Melville. Alton was closer. So was Charleston. But the Orangeville Sun made it to the Melville post office on Thursday and often didn’t reach the other villages until Friday.

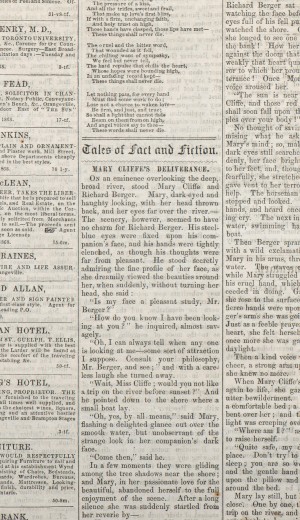

On May 13, the previous Thursday, a column on the front page of the Sun had ended abruptly with “To be continued” – just as demure and delicate Mary Cliffe had inflamed the vindictive Richard Berger by refusing his proposal of marriage. Matilda simply had to know what happened next – and so did her neighbours (although they didn’t always admit it).

On May 13, the previous Thursday, a column on the front page of the Sun had ended abruptly with “To be continued” – just as demure and delicate Mary Cliffe had inflamed the vindictive Richard Berger by refusing his proposal of marriage. Matilda simply had to know what happened next – and so did her neighbours (although they didn’t always admit it).

There really was a Matilda Clark. Her property was on the Second Concession East of Caledon Township in 1869, but whether she actually walked to Melville we can never know. The appeal of romance fiction, however, a weekly serialized feature in the Sun, was so powerful that her effort was entirely possible. Matilda’s world had no radio, no television or movies, few books and fewer libraries, but, just as today, everybody enjoyed a good story, and weekly newspapers cleverly responded to that desire.

Much more on offer

As a feature, the weekly story was extremely popular, but Matilda and other readers of the Sun didn’t subscribe only to binge on soap opera, for their newspaper also had far more serious material on offer.

To begin with, there was a range of local and national news and updates on the world at large. There were instructional and informative essays – columns – on a variety of topics. The May 13, 1869 Sun, for example, told how cork is harvested, mused on the biblical significance of the number three, and warned of the dangers of eating opium. There were health and wellness columns and reports from all levels of government. Readers could count on notices of coming events such as church socials or auction sales (although on May 13 they were outshone by a list of strayed and missing livestock).

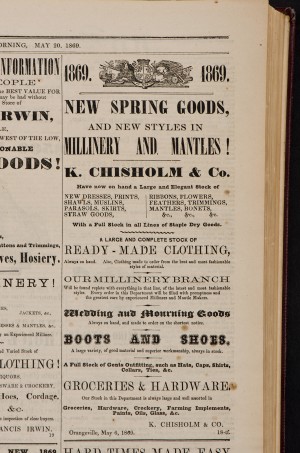

Always prominent and carefully perused were the space ads, the advertisements. A business and professional directory was a standard feature, along with “fill” of a lighter vein – poetry and vignettes varying from trivia to gentle jokes (called “Sunbeams”). Above all, every issue of the Sun had editorial comment which was widely read, for publisher John Foley was notoriously outspoken.

A mighty task

Weeklies like the Sun were pretty much one-person operations, so in addition to selling ads and managing the business, the John Foleys of their day had to gather and write the news, write editorials (or as often happened, insert editorial comment into the news), do the typesetting, layout and printing – and then see to distribution.

Weeklies like the Sun were pretty much one-person operations, so in addition to selling ads and managing the business, the John Foleys of their day had to gather and write the news, write editorials (or as often happened, insert editorial comment into the news), do the typesetting, layout and printing – and then see to distribution.

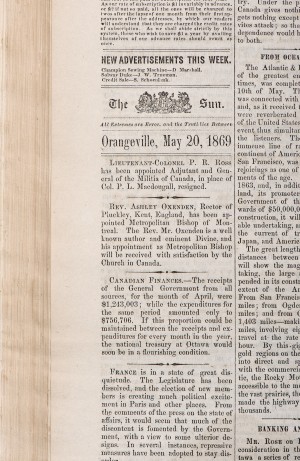

Given that huge labour demand, the Sun was a surprisingly sophisticated and cosmopolitan newspaper for its era. In part, that was because Foley took advantage of outside services. For much of its early life, his was a four-page newspaper. Two broadsheets arrived in Orangeville every week prior to the Thursday printing, with international and national news, the essays, the popular fiction, the fill and some ads already printed. However, there were also sections of the layout left blank for the insertion of local ads and news, or other items Foley wished to include at his own discretion. As a consequence, the Sun, like many local weeklies of the day, managed to provide something for everyone.

Something for everyone

When Matilda Clark and her neighbours in Caledon Township got their copies in May 1869, odds are that after checking on the fate of Mary Cliffe, they turned immediately to local news. At the time, the Toronto, Grey and Bruce Railway was slated to come through their township to Orangeville and news of this important development was eagerly anticipated. Subscribers in Amaranth, on the other hand, would have been immediately drawn to page three which contained the yearly audit of the township’s finances.

Detailed items like audits often took up significant space because a local paper was almost the only way for governments to disseminate reports or advise of upcoming legislation and policy. Along with that Amaranth audit, for example, the Sun published a detailed explanation of Ontario’s new school legislation which, among other things, set up collegiate institutes (males only) and dictated minimum teacher salaries (male, $300/annum; female, $200/annum).

National news was rather uneventful in 1869, except for reports on the Fenians and the fear they would bring their Irish nationalist fervour to the hills. (Things heated up a lot a couple of years later when the Pacific Scandal famously blew up in the House of Commons with accusations that MPs were taking bribes to influence the national railway contracts.)

International news covered items like the activities of British royalty and happenings in the U.S. The May 20 issue that we imagine so intrigued Matilda Clark touched on the completion of the Suez Canal, and included news from countries as varied as Mexico, Turkey and Prussia. The news was general and it was brief, but for people in the hills, it was a window on the world.

Above all, a local, personal flavour

Foley had a masterful understanding of a readership that was essentially rural and comparatively isolated. Major local news would get entire separate columns. In May 1869, he reported in depth on discussions about the creation of a new county (eventually to be Dufferin). The coming railroad always got space, as did human interest stories if they were both local and unusual, like the farmer from Mono who, in “a state of partial inebriation” choked to death on a piece of meat.

Foley had a masterful understanding of a readership that was essentially rural and comparatively isolated. Major local news would get entire separate columns. In May 1869, he reported in depth on discussions about the creation of a new county (eventually to be Dufferin). The coming railroad always got space, as did human interest stories if they were both local and unusual, like the farmer from Mono who, in “a state of partial inebriation” choked to death on a piece of meat.

Items deemed of lesser significance were published under “Orangeville and Vicinity,” a catch-all title typical of all weekly papers. (The Bolton Enterprise used “Localettes.”) These items included short bits such as the price of potatoes, a barn fire in Caledon, a conference of doctors in Fergus, and a boy who found and returned a lost wallet (with $69!) in Alton. In this section Foley often reported the recent arrival of goods at local retail stores, “news” that coincidentally also appeared in large ads on the next page.

Because they were the biggest source of revenue for the Sun, ads took up a significant amount of space in every issue. Yet these too were a kind of community service, offering kitchen-table information readers genuinely wanted, telling people what was available and where, and in the process reassuring them that their community offered a lifestyle equal to any other.

All this was put together faithfully every week by a publisher who was an enthusiastic booster of his predominantly Protestant community even though he was a Roman Catholic. Although readers might have expected a jab or two from someone who never hesitated to do just that (Foley cheerfully slagged competing newspapers in almost every issue), he regularly and fairly reported Orange Lodge news because it was local and important. It helps explain why in its day, especially in its early days, the Sun was a vital part of the glue that connected these hills and made them a community.

(Incidentally, as Sun readers discovered, the dastardly Berger was consigned to a watery death after failing to take Mary Cliffe down with him. She was ultimately united with her true love, and readers moved on happily to a new “tale of absorbing interest” called “Woman’s Kingdom.”)

Did you know?

Orangeville’s newspapers were pioneers of gender equality

The early history of the press in Orangeville can lay claim to some quite forward thinking in terms of gender equality. When the Orangeville Sun’s founder John Foley died in 1882, his son John Foley Jr. took over at the tender age of 16. A frequent contributor from that point was John Jr.’s sister, Margaret, who wrote especially persuasive editorials. Margaret’s contributions are remarkable not just for their content and for the respect they were given by readers, but for the fact, in those days, that they were written by a woman.

When the editor/publisher of the Orangeville Banner, Alexander McKitrick, died in 1949, (the Banner began publishing in 1893) his daughter Helen (McKitrick) Matheson, ran the paper with her brother Victor. Helen was a prominent contributor to the Banner, and like Margaret Foley, was especially respected as a editorial writer. The prominence of both Helen and Margaret in these weekly journals indicates that the Foley and McKitrick families, as well as the people of these hills, were more open-minded for their day than some histories suggest.

Newspapers have a long history of political bias

In October, 2015, when Postmedia newspapers in Canada were commanded to place support for the Conservative Party on their front pages for the federal election, thus shocking many Canadians, the chain was actually reprising a well established tradition from the 19th century. In Orangeville, the Sun was completely and vociferously supportive of the Tory party of Sir John A. Macdonald. The Sun’s chief competitor, The Advertiser, founded in 1869, enthusiastically supported the Liberal Party, an uphill task in these hills at that time, so by 1874, The Advertiser packed it in.

However, that was good news for Shelburne. George Raines, who had worked for the Sun before running The Advertiser, took his talent and his press to Shelburne and began the Free Press. By 1883, the community had a second weekly, The Economist. The two papers amalgamated in 1903.