Home After Supper

Evening meetings are just one of the demands that come with the job for local councillors, and there are plenty of others, but for most who take the plunge into public service, there are also rewards. Four former councillors reflect on the highs and lows of life in the council chambers – and after.

Like a rare cactus that blooms only once every four years, municipal elections are upon us. Unlike the cactus, the politician’s intention to flower is announced months before, with press reports that candidate X or Y has filed nomination papers. You know the buds are forming when suddenly politicians are everywhere – the farmers’ market, the community meeting, the town festival.

When petals begin to appear in September, they are smooth and silky – some even a little slippery. Sporting a variety of colours, they all exude the sweet scent of success. By October, every flower has opened and there’s a come-hither display of empathetic smiles, let’s-do-lunch handshakes and baby-kissing photo ops, while promises fill the air like clouds of pollen.

It all culminates in a crescendo on the fourth Monday of October, the day some flowers are chosen, but many are left to wilt on the vine.

Then it’s over. Scattered at the feet of the victors, the losers’ blooms are swept up for the compost. Forgotten, like so many lawn signs in the back corner of a garage.

But even for the victors, sprouting roots in a council seat can be a precarious business. Some cacti resume their thorny hide, but many tender plants fall victim along the way. Survival requires the determination of a June dandelion, a lot of growth, the pruning of some ideas and, just maybe, the occasional application of a well-known organic fertilizer.

Some politicians will thrive and branch out. For some, local politics is a hothouse of growth that leads to a lifelong career in public service.

Former Mono mayor John Creelman and former Caledon mayor Carol Seglins, for example, have both gone on to become provincial Justices of the Peace. Ironically, as Justices, the two former politicians are restrained from commenting on details of their municipal experience. Still, both are quick to encourage anyone who is considering running to take the plunge. “I’ll always miss it,” says Seglins. “I loved every minute of it. But I also love my new challenge.”

Former councillor Beverly Kumprey is taking on new challenges too, though after twenty-seven years things must seem pretty strange in Melancthon without her.

Kumprey spent twelve years working at the township hall before trading her office chair for a council seat. Now, five terms and fifteen years later, it’s fair to say she knows how to get a thing or two done.

Kumprey’s feelings are far more positive feelings than negative about her tenure. “I really enjoyed it. Each election I would get a respectable count, so I always felt the residents thought I was doing a decent job.” She acknowledges that when dealing with electors, “Sure, you get the odd rude one, but it’s not personal. You just have to be tough and let stuff wash off your back.”

Kumprey is particularly pleased with her contribution to the township’s tax policy. “I guess I feel it’s an accomplishment that I was part of decisions that resulted in Melancthon having the lowest tax rate in Dufferin. I think we also have the lowest administration costs. And we maintain 167 miles of road.”

Still, that same property tax bill was an ongoing irritant. “I’d have to check the exact numbers, but as I recall, it was about 28 per cent that went to education, and another 36 per cent went to the county. We have no say in either of those amounts. And what’s left? How are we supposed to run the township?”

Beverley Kumprey

High: “I feel it’s an accomplishment that I was part of decisions that resulted in Melancthon having the lowest tax rate in Dufferin. I think we also have the lowest administration costs.”

Low: At the municipal level, “you’re dictated to about everything. You always have to be aware that you’re at the bottom … We know what’s best, but often have no say. Yet we’re the caretakers of the land.”

And to Kumprey, monitoring taxes is more than simply an exercise in frugality: “High taxes often mean families must have two incomes.”

Councillors’ incomes are one of the things those taxes finance. It isn’t uncommon for councils to defer giving themselves a raise for years, simply because it’s politically unpopular. Eventually, though, it’s catch-up time, and then the percentage increases can seem huge. In 2008, Orangeville studied how much councillors were paid in other municipalities and attempted to bring their own council remuneration in line, but that meant the mayor would receive a whopping 61-per-cent increase, councillors 36 per cent.

The result was a public revolt that drew more than a hundred residents to protest at council meetings. Council eventually reversed the pay increases and appointed a committee to study the matter further. It found that Orangeville councillors were paid an average of 35 per cent less than those in eight similar-sized municipalities. Significant increases, though less than first proposed, will be in effect for Orangeville’s incoming council.

There’s also quite a wide range in pay rates across the region. The base rate for a local councillor in Melancthon, for example, is a little over $8,000, while a Caledon councillor who also sits on upper-tier Peel regional council, receives a base rate of a little over $78,000. All councillors are paid extra for things like mileage, benefits and committee work.

Although Melancthon’s part-time, five-person council has been facing some tough issues lately, including industrial wind farming and a rumoured mega-quarry, Kumprey feels she was adequately paid for her work.

Pointing out that “the position was volunteer when municipal councils first started,” she stresses community over compensation: “There’s a different atmosphere in rural politics. You know everyone. I’ve received more than a hundred nice letters since my retirement. I know, young people demand to be paid. It’s no longer the pleasure it once was.”

It’s not unusual to hear local politicians complain that their hands are tied by upper levels of government, and to a jaded electorate that can seem like little more than a handy excuse to dodge responsibility. However, Kumprey argues that there’s truth to the claim. “You’re dictated to about everything. You always have to be aware that you’re at the bottom, and then ask how many decisions can we make? We know what’s best, but often have no say. Yet we’re the caretakers of the land.”

Kumprey retired a few months before the end of the current term. With health problems that affected her mobility, she found some aspects of the job too demanding. “I couldn’t get out and inspect a gravel pit or property any more, and I just felt you need to be able to do things like that to do the job properly.”

Kumprey says she would have run again if her health had permitted. On the other hand, she now has the time to indulge another interest. “Once in a while I take a trip to the casino. I could never have admitted that when I was a politician, because I’d be afraid someone would claim ‘She’s taking our tax dollars and blowing them at the casino!’ Even if they didn’t, I’d feel guilty anyway.” A moment later, she adds “Actually, I still do.”

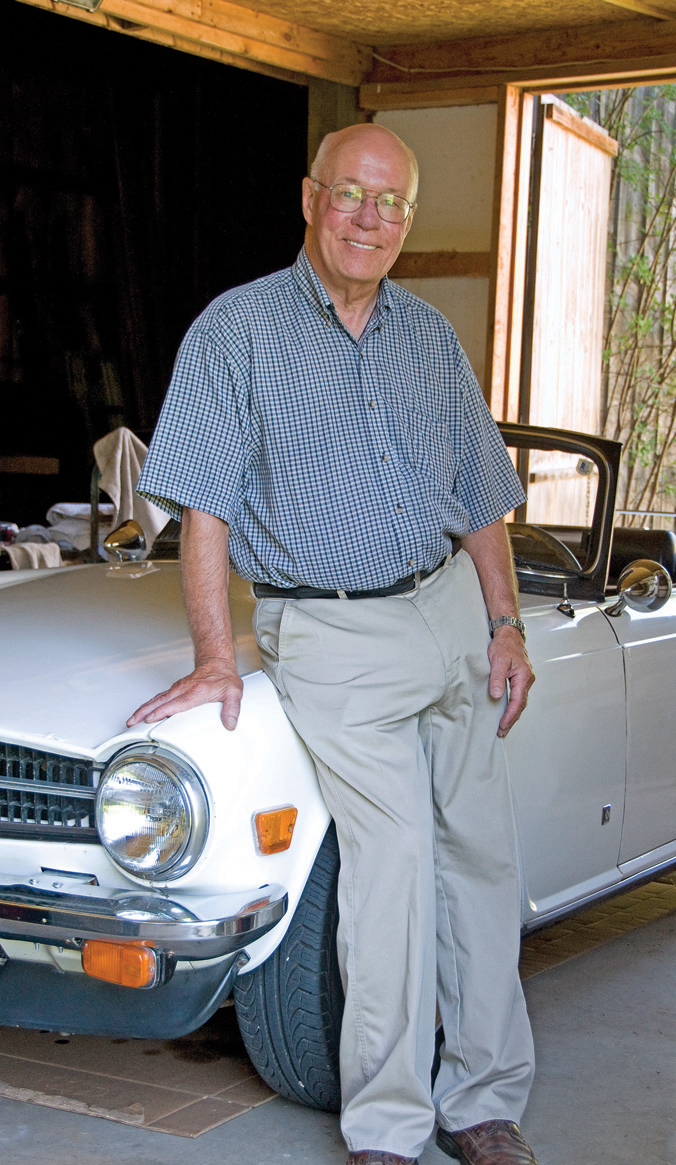

For former Amaranth councillor Ron Pincoe, who served one term in the 1990s, just getting elected was an extended crap shoot.

On election night there was a tie. Only two spoiled ballots separated him from his nearest opponent. It took an official recount and two court cases before Pincoe was finally declared the victor.

Pincoe began as what is known as a “one-issue candidate.” He ran specifically to try to prevent Orangeville from annexing parts of Amaranth during the municipal amalgamation craze of the Harris government. One-issue candidates are susceptible to criticism that they lack of understanding the big picture, but Pincoe sees it differently: “So what if a particular concern gets someone involved? They’re still getting involved.”

Ron Pincoe

High: “A great feeling comes from helping somebody, letting them know someone cares. My three years were a great growing experience.”

Low: “I tended to take issues to heart and wanted to help everybody. I’d get frustrated when I couldn’t do it, either because I was handcuffed by the rest of council, or by the province … People don’t understand what council can really do. They think they can do everything, not realizing how limited their power is.”

Furthermore, he says, candidates are bound to gain more knowledge of voters’ concerns as they make their way on the campaign trail.

Once his seat was confirmed, Pincoe became one of three neophyte politicians on a council of five. “A steep learning curve went on,” he says, emphasizing the importance of having some more experienced council members on board. “And the clerk was a great help.”

Pincoe was sensitive to the very personal nature of some issues that come up for councillors. He recalls one occasion when a couple with a young child came looking for help. They were renting a farmhouse, and the landlord refused to properly seal an open well located nearby. Fearing for their child’s safety, they approached the township. “At the time,” Pincoe remembers, a note of regret in his voice, “the township didn’t have a property standards bylaw, so we couldn’t go after the owner. All I could do was tell these people, ‘I can’t do any more.’”

In his experience, “People don’t understand what council can really do. They think they can do everything, not realizing how limited their power is.” And he echoes Kumprey’s frustrations with the province.

Take provincial road standards as an example. “The township has to build to meet the standards, and pay for it. So let’s say we have a narrow little country road that needs a new bridge. We end up spending $300,000 for some great big bridge that’s wider than the road that leads up to it.”

On the positive side, Pincoe is proud of his work to advance recycling in Amaranth, and of his time spent working with fellow Amaranthonians. “A great feeling comes from helping somebody, letting them know someone cares,” he says, encouraging people to get involved. “My three years were a great growing experience.”

So then why did he quit after only one term? “I wasn’t cut out to be a politician. I tended to take issues to heart and wanted to help everybody. I’d get frustrated when I couldn’t do it, either because I was handcuffed by the rest of council, or by the province.” Also, he adds, “Some people have a thick skin, but for me, we’d get a bunch of residents turn up as a delegation to council for some issue, and afterward I’d find it bothersome.”

At the south end of the hills, former Caledon councillor Al Frost won’t tell you how much he loved being on council, nor wax nostalgic about the glory days.

Like Pincoe, Al Frost got involved as a one-issue candidate. In the late 1980s, a coalition of taxpayers ran a slate of anti-tax candidates. Frost was one of them, and he was elected as an area councillor for Ward Two. He subsequently served three terms, but he’s a harsh critic of his own tenure. “My first term was the most productive. I did okay in the second term, but by the third term I shouldn’t have been there.”

He says working as a cog in the machinery of government gradually wore him down, and he admits, “I’m a bit bitter. I have very little tolerance for unending process.”

By way of example, he points to a provincial search for a new landfill site that went on for years in the 1990s and identified numerous potential locations in Caledon. “That process cost the province $63 million, got everybody up-in-arms, and ended up with no dump … the whole thing was a complete waste of time.”

Al Frost

High: He counts holding to a zero tax increase throughout his nine years on council as his most significant accomplishment in office.

Low: Working as a cog in the machinery of government wore him down. “I have very little tolerance for unending process.”

Then there were the lawyers. Frost was in management at Eaton’s department store, responsible for product testing and safety. Even in such a potentially litigious situation, he says, “we maybe consulted a lawyer once or twice a year. But at council, it was numerous times every meeting.”

Frost was also frustrated by the power of senior municipal staff. “On Thursday I’d get the package of material for the council meeting on Monday night, typically supplemented with staff reports and recommendations covering whatever was inside. Nine times out of ten that would be the vote of council.”

He feels that’s especially true of financial matters. “Council bends too easily to staff on taxes.” He thinks municipal government should run more like a business. “They don’t look at it from the revenue side. For them, if there’s a shortfall, it’s called a tax increase.”

Little wonder then that Frost counts holding to a zero tax increase throughout his nine years on council as his most significant accomplishment in office.

Though he’s been asked, it’s unlikely you’ll find Al Frost’s name on the ballot again any time soon. “No, I won’t run again. I’d come home from some meeting, and my wife would say ‘You’re going to have a heart attack.’” Echoing Ron Pincoe, he says, “I’m not cut out for politics.”

Former Erin councillor Jeff Duncan also says “no, I don’t think so” when asked if he’ll run again, but the wistful tone of his voice says “maybe someday.”

Duncan’s introduction to politics occurred when he appeared before council as part of a community delegation about a local issue, the municipal purchase of a millpond in Hillsburgh.

That experience “made me think I wanted to take part, to help facilitate good ideas. Some guys volunteer for the fire department. I thought it would be a way to help pay back. So when I got on, it wasn’t about change, but about finding the best ways to consult and foster co-operation.”

Of course, that’s not as easy as it sounds, as Duncan notes, on council “you don’t get to pick your team. You have to make the best of it and play the cards you’re dealt.”

As a result, he says, “to get things done can be difficult. I found the best way to achieve something was to take the bull by the horns and run with it yourself.” In that respect, Duncan says he was lucky, “because the mayor always gave me enough rope to either pull it off or hang myself.”

Still, success in politics is rarely a one-person show. Says Duncan, “Whatever you bring forward, you only have one vote. Even the mayor only has one vote. You have to get buy-in at the committee level, from the staff, and then from council.”

Daunting as it seems, achievements are possible, and Duncan points to several examples from his own experience.

Erin was the only near-urban municipality that did not have a full-time planner. “We’re right next door to Caledon, who I think has a planning staff of more than twenty.” Duncan, whose own day job is with a professional planning firm, says, “I had an idea of the limitations that created for the town, so I count Erin getting its own planner as an accomplishment.”

However, he is probably best known for the creation of Erin’s heritage committee. When he began his term, he says, “if someone wanted to tear an old building down, there was nothing to prevent it happening.”

Duncan oversaw the creation of the committee and chaired it for five years. In that time, the committee developed an inventory of heritage buildings and worked with a developer to preserve a stone building, thought to be the first dwelling in Erin, at Crewson’s Corners. The project subsequently won an Ontario Heritage Award.

He says the most personally meaningful experience during his public service took place in April 2007, when he travelled to Vimy Ridge in France to lay a wreath on behalf of Wellington County’s WWI veterans and their families.

Duncan even took lessons from the election process itself. “I’ve learned that ideas come from all the people who run. The people who bring them forward may not win, but the ideas still come forward.”

It wasn’t all clear sailing though. Duncan found the variable pace of activity a particular challenge. He feels some things, such as provincial adjustments to municipal council terms and the Greenbelt legislation, happened too quickly or without local consultation, while others, such as dealing with municipal infrastructure deficits, happen glacially or not at all.

And he has other quibbles: “The province has so many different policy initiatives going at the same time, it’s hard for municipalities to keep up. Another beef I have with the province is about reporting requirements, which are a big drain for local municipalities. There’s so much time-consuming red tape. You only have limited staff and if they’re focussed on that, they’re not doing other local things.”

Jeff Duncan

High: “I loved being on council. I found it very rewarding, and the number of people you get to meet is incredible.” Being elected is “really humbling. It’s the reason why you give the job your best effort.”

Low: “The province has so many different policy initiatives going at the same time, it’s hard for municipalities to keep up… There’s so much time-consuming red tape. You only have limited staff and if they’re focussed on that, they’re not doing other local things.”

But there is one area where Duncan would like to see more provincial control, not less: “The province has a thousand and one rules around the environment, but it’s still up to the local municipality to manage infrastructure. You would think the province would be more directly involved, particularly with funding.”

Despite the frustrations, it’s clear Duncan means it when he says, “I loved being on council. I found it very rewarding, and the number of people you get to meet is incredible.”

Although he topped the polls in the two terms he served, rather than seeing it as a licence to coast, Duncan says, “It was really humbling. It’s the reason you give the job your best effort.”

Still, he decided not to run in 2006. At the time, four people close to him had been diagnosed with cancer. “That factored in the decision more than I realized at the time,” he says, “but the main issue was the time commitment.”

Duncan says he attended about sixty to seventy meetings a year. For councillors who actually read the mountains of material they receive, preparation time for that kind of meeting load is huge.

“You’ve got family, a full-time job, and then council. You can’t do all three, so something suffers,” he says. Worse yet, some committees meet during the day, so he would take vacation days from work to attend. With only three weeks annual vacation from his job, not much time was left. “Plus I commute an hour a day. It was becoming too much of a struggle.”

Perhaps Duncan sums up the reality of life in municipal politics most eloquently when he says, “You forget what it’s like to be home after supper, and have to deal with the dirty dishes.”

************

Another Day at the Office

For every new municipal politician, there must be a moment of white-knuckled, sweaty-palmed self-doubt. At least we should hope there is.

It arrives after the victory celebration is over, around the same time they sit down to read The Municipal Councillor’s Guide. Produced by the ministry of municipal affairs and housing, this seventy-three page tour of life as a municipal councillor is enough to make anyone gulp about what they’ve gotten themselves into.

Who’s your daddy?

One thing the province wants new councillors to understand concerns who the boss is. The document points out that there is no provision for the existence of local municipalities in the Canadian constitution. Instead, municipalities are a creation of the provinces and, as such, “may only do what they have been authorized to do by the provincial government.” Legalese for “Get too big for your britches, and we’ll squish you like a bug.”

Three roles

1. Representative role

In theory, municipal councillors are elected to represent the views of their con-stituents as closely as possible. In practice, though, it’s impossible to represent all constituents’ views all the time, so complete agreement on any issue is very rare. As a result, councillors are directed to make decisions based on the long-term health and welfare of the community, and to represent constituents by “providing the services and programs that they need, not everything they want.” But distinguishing between “needs” and “wants” can be the trickiest part of the job.

2. Policy-making role

As policy-makers, councillors have their greatest opportunity to shape what the municipality looks like. Policy extends beyond the four-year term of office and may guide decision-making well into the future. Policy may be specific, such as “no skateboarding downtown,” or broad, such as approval of an official plan.

An established process guides development of policy. Usually, council directs staff to look into an issue and report back. Council then debates and refines the policy and directs staff to implement it. Often, a policy may also be sent to committee for study.

It all sounds fairly straightforward, but in practice things get messy. Issues can change rapidly, or simply be too complex to analyze thoroughly in the time available. There are rigid limits on what municipalities can do, both legally and financially. Sometimes the idea may be good, but the machinery needed to implement or monitor it is too cumbersome to maintain.

3. Stewardship role

In a way, election as a municipal councillor is a bit like being elected mom. As stewards of the municipality, they are responsible for making sure the bills are paid, there’s some cash in the bank, no one is leaving the lights turned on, and that everyone is generally behaving themselves. It’s a tricky job, because there’s a fine line between council’s duty and the day-to-day management responsibilities of staff. Without necessarily kowtowing, a councillor who works well with staff is likely to find life a lot easier than one who doesn’t.

Upper-tier and lower-tier

Upper-tier government is the regional or county council. It typically provides services of broader scope, such as regional planning, or where greater efficiencies can be achieved collectively, such as for waste management or the operation of a seniors’ home.

In Ontario, upper-tier councillors are usually elected indirectly, meaning membership is automatic for the heads of lower-tier councils and certain other councillors, such as deputy mayors. This is the case in Dufferin.

However, in some municipalities, including Peel and Wellington, upper-tier councillors are directly elected by voters.

Lower-tier government is the town or township office that most people think of as “town hall.” There are those who feel lower-tier government should more rightly be called “local” government, because the tier reference suggests regional government is somehow more important or powerful.

Committees, local boards and special purpose bodies

Municipal councils have a wide-ranging workload. One way they get it all done is through the creation of committees. These can be either “standing” committees, made up of only councillors, or “advisory” committees, made up of a mix of councillors and public appointees. These committees do a lot of the heavy lifting, studying issues and reporting back to council with recommendations. Examples include parks and recreation, heritage, finance and planning.

A huge assortment of other boards and special purpose bodies are engaged in the delivery of public services. They have varying degrees of independence from municipal council control. Some, like the police services board and library board, are mandatory. Others are created at council’s discretion, and council has the power to shut them down if conflicts arise. A trail committee might be an example of that.

Still other public bodies exist entirely outside council’s control. Hospital boards, boards of health and conservation authorities operate independently, though in some cases the municipality may have an opportunity to appoint a member.

School boards operate entirely separately from council. Curiously, while school boards usually command a majority of the property tax bill, public representation there is dramatically lower. For example, where Orangeville has seven municipal councillors, it has only one elected representative on the Upper Grand District School Board.

Lawmakers

The Municipal Act gives each municipality a variety of powers falling into several categories: Natural Person Powers, which permit it to do anything a person or corporation could do, such as hiring people or buying land; Broad Permissive Powers, which allow the community to decide its own form of governance and make decisions about how it will operate; and Spheres of Jurisdiction, which may be shared or divided between upper- and lower-tier governments and provide the power to pass bylaws concerning:

- Highways, including parking and traffic

- Transportation systems, other than highways

- Waste management

- Public utilities

- Culture, parks, recreation and heritage

- Drainage and flood control, except storm sewers

- Structures, including fences and signs

- Parking, other than on highways

- Animals

- Economic development services

- Business licensing

At the same time, there are a multitude of limitations on what councillors can do with their wizard-like powers. Short advice here: As a councillor, you’re going to get to know your friendly municipal solicitor. Really well.

Money

The Municipal Councillor’s Guide warns, “The learning curve may be steep as you investigate how your municipality’s financial processes operate.” The accompanying brief review of where the money comes from, how it’s spent, and how to keep track of it all must make new councillors think that some other part-time job – say spaceship navigation – might have been an easier choice.

First there’s preparation of the municipal budget. Sort of like an annual birthing process where, line by line, revenues and expenses are tallied up. There is perhaps a misconception that town hall operates solely on property taxes. In fact, municipalities have a variety of income streams, including grants from other levels of government, user fees for facilities like the arena and services like garbage, licensing, fines, investment income and development charges.

On the expense side, there are capital expenditures and operating expenditures. The capital budget includes tangible assets, including anything from new traffic signals to upgrading the sewage treatment plant. On the operating side, there are things like repairing traffic signals and fixing the leaky roof at town hall, as well as ongoing costs like fire and police protection.

In many cases, rapid growth and/or aging infrastructure place tremendous pressure on municipal finances. Councillors are responsible for not only effective financial management, but also ensuring that taxpayers are receiving good value for their tax dollars.

Land-use planning

A large part of life as a municipal councillor is taken up with planning matters, and it’s where they are likely to bump into the most voters.

As the elected local representatives, councillors are at the centre of decisions regarding land and resources. It’s a complicated dance with proponents of development projects, the public, the province, and the Ontario Municipal Board. In theory, the steps are called by the municipality’s official plan and zoning bylaws; however, the content of those documents must conform to the Provincial Policy Statement, so the province ultimately calls the tune.

Councillors are also likely to confront the subdivision development process, and require an understanding of land severance.

Public participation is a mandatory element of land-use planning. When considering a development plan, councillors are required to take a balanced view, factoring in public input along with environmental, social and financial costs and benefits.

While land-use planning decisions are often controversial, the process provides the best opportunity for shaping the future of the community – the most enduring legacy of an individual’s time in the council seat.

A striking common factor among the former counsellors you interviewed is that frustration arises as the restrictions imposed by the Ontario government on local government are realized.

It does not make sense to centralize rural planning in a Toronto high-rise when the workers there have never walked a pasture or woodlot.

Charles Hooker on Sep 28, 2010 at 12:07 pm |