The Love Pirate

Dufferin County was briefly home to Andrew John Gibson, an Australian who became one of the most well-known con men and bigamists of the 20th century.

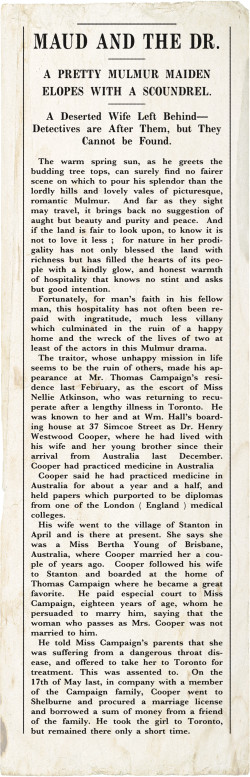

In the late 19th century, rural Mulmur Township figured fleetingly in the criminal career of Andrew John Gibson, who left a trail of misdeeds and broken hearts across the United States and the British Empire. Some even claim that this charlatan may have been the infamous Jack the Ripper.

Dufferin County was briefly home to Andrew John Gibson, an Australian who became one of the most well-known con men and bigamists of the 20th century. Gibson may have used as many as 40 aliases, but residents of Mulmur Township, where the swindler turned up in 1897, knew him as Dr. Henry Westwood Cooper.

Gibson was born in Australia in 1868, but spent his youth in England, returning to Australia when he was 20. The young man used his time in England to good advantage, often claiming to be a member of the British aristocracy or attached to the royal family. An expert forger, Gibson was known for drafting false cheques, cables, family trees, credentials and official letters explaining he was due absurd sums of money.

One ultimately unsuccessful attempt illustrates Gibson’s skill, as well as his audacity. In 1925 he was arrested after passing documents authorizing payment from the South Australian Treasury. The documents appeared to have been signed by South Australia’s minister for lands – and Gibson was caught only because he passed identical notes at two banks at once. The judge in the subsequent trial declared Gibson a forger “in the first rank.” There are also reports that while Gibson was in his 20s, he posed as a “Baron Chadwick” and duped a widow in Sydney of her savings, escaping conviction only on a technicality.

In 1891 Gibson married Frances Mary Skally, then 21. The two-year difference in their ages was the least of any of Gibson’s early marriages. He seemed to prefer much younger women – or perhaps he just found them easier to manipulate. What happened to Skally isn’t clear, because most reports refer to Helen Scott, the 15-year-old Gibson married in 1895, as his first wife. A year later the fraud artist married Bertha Young, 17, and the two set sail for England to pick up one of Gibson’s (presumably phantom) inheritances.

The couple didn’t make it to England. Instead, they stopped in Canada and settled briefly in Toronto. There, posing as Dr. Henry Westwood Cooper, Gibson, who had no formal medical training, was introduced to Nellie Atkinson, who was being treated for consumption. When Nellie returned to her home in Stanton in February 1897, Gibson went with her, accompanied by Bertha.

Gibson cut an impressive figure in Stanton, which was still a relatively busy community south of Mansfield on what later became Airport Road. According to the Orangeville Sun, Gibson’s “standing in social circles was assured from the first.” He claimed to be a demonstrator and lecturer at the Toronto General Hospital, and showed forged reports on the “marvellous feats in surgical operations” he had performed.

In a testament to the credulity of some local residents, a number of patients demonstrating vague symptoms appeared and were cured with little more than his “magic touch.” What made Gibson’s accomplishments and pedigree even more impressive was the fact he was only 27. He also seemed interested in settling in Stanton.

But not everyone was convinced. Why would a member of the British aristocracy, with a medical degree from London and world-class skills, want to settle and practise in rural Stanton? The murmurs grew, but Gibson threatened legal action against his defamers, who were evidently in the minority. He was considered upstanding enough to be asked to lecture from the pulpit of Stanton’s Presbyterian church.

Perhaps as a way of lending credence to his claims, Gibson made a show of being in delicate health and drew up detailed wills leaving outrageous sums of money to his new Stanton friends.

His illness, real or not, brought him into close contact with Ida Maud Campaign, who was appointed to wait on him while he boarded in her father’s home. This was a dangerous situation for 18-year-old Maud.

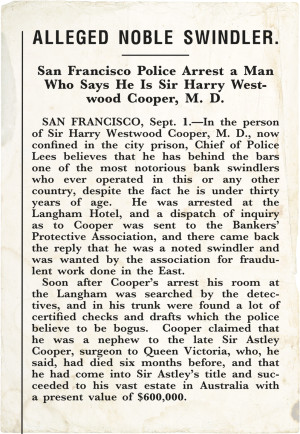

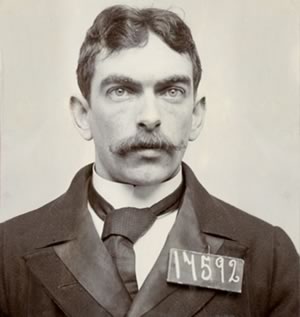

In the eyes of the San Francisco police, with whom Gibson later become very well acquainted, there was nothing particularly attractive about the con man. He was short and weighed barely 150 pounds. But he was said to use his voice on women in the same way a snake charmer used an instrument to hypnotize snakes. Gibson himself had once boasted, “Give me a shave and a clean shirt and I can win the affection of any woman in the world.” It certainly seems to have worked with Maud. By that May, she had agreed to marry him.

Andrew John Gibson, aka Charles Ernest Chadwick, aka Charles Edward Chadwick, aka Sir Harry Westwood Cooper MD, aka Harry Westwood Cooper, aka Dr Milton Abraham, aka Walter Thomas Porriott, aka Dr Harry Cecil Darling.

Gibson and Maud’s courtship occurred under the nose of Bertha, who was also staying with the Campaigns. Gibson told people that he and Bertha were travelling together under false pretences, and that she was not his real wife. To a certain extent this was true, but only because he was still married to Helen Scott – and Bertha later used this argument to win release from the marriage.

If word of the engagement had gotten out, it would not have held up to scrutiny. So Gibson told the Campaigns that Maud had a throat disease requiring immediate surgery that could be performed only in Toronto. In the meantime, Gibson and Maud slipped off to Shelburne and obtained a marriage licence. A prominent citizen of Shelburne lent the couple money to finance their plan.

Bertha accompanied the two to Toronto, acting as chaperone, and stayed with Maud in a boarding house. Maud was supposedly going to an aunt’s, and when she had done so, Bertha was to return to Stanton where her husband would rejoin her. But when Maud left, it was to marry Gibson.

The couple disappeared, leaving Bertha to take the train north, where she would receive the nasty surprise. Gibson performed the same disappearing act many times over the course of his career, and no one is sure how many wives he left behind. When Maud was inevitably deserted, she returned to Mulmur where she eventually married into the Greer family.

It has been said that Gibson’s life was one long honeymoon, and it might be called that – at least when he wasn’t serving one of his many prison sentences. He spent about 44 years in jail, most of his prison terms lasting only a few months or years. He is alleged to have married somewhere between 13 and 20 women, usually staying around only long enough to exhaust his new bride’s savings and credit, or the credit of her friends. He was so persuasive that his prison guards were sometimes forbidden to talk to him because he was liable to ask for special exceptions and to take full advantage of them when they were inevitably granted.

From Toronto Gibson proceeded to San Francisco, then South Africa, England and Australia. He followed the same path, serving many sentences for fraud and continuing to practise as an unlicensed physician. He was already a known bigamist when he served time in San Quentin State Prison near San Francisco, but this didn’t stop him from secretly marrying a female evangelist who often visited the prisoners. Like the others, that marriage didn’t last long.

Indeed, nothing in Gibson’s life seems to have lasted very long, and he left California in a hurry, just as he left everywhere else. But law enforcement officials clearly considered him major quarry. In 1914 the Oakland police apparently thought it worth sending an officer 10,000 miles to Johannesburg, South Africa, to bring Gibson to justice on several charges, including bigamy.

Though Gibson’s misdeeds need no embellishment, the Australian press has recently featured speculation that the con artist might have been the infamous Jack the Ripper. The most compelling evidence against Gibson may be that he was in London in 1888, when all five of the Ripper’s “canonical” brutal murders were committed, and that he set sail for Australia on the day the final victim, Mary Kelly, was found.

Ripper researchers have also cited statements Gibson made in Health and Vigour, a book he published in 1914, as evidence pointing to his guilt. In the book, he claims prostitutes are the cause of all diseases and women who trade in sex should be wiped out with “an axe at the very roots of this deadly evil.”

However, by some accounts, hundreds of men are likely Ripper suspects, and Gibson is nowhere near the top of the list. Although he was a misogynist, his exploitation of women seemed primarily for financial gain and self-aggrandizement. Furthermore, although Jack the Ripper was thought to have a broad knowledge of anatomy, Gibson was not a competent doctor. He had learned anatomy to bolster his fraudulent schemes and he left a full set of medical textbooks to relatives upon his death. But he was also very young – no more than 20 years old – when the still unsolved murders took place.

The worst crime anyone can be sure Gibson committed was his role in the 1939 death of Gladys Higginbottom. She came into his care while he was impersonating a doctor at the City Maternity Hospital in Stoke-on-Trent, England. She was in serious condition when admitted, but he ignored her, finally inspecting her in “a very amateurish way” only two hours before her death. For this, Gibson, who was 72 at the time, was convicted of manslaughter and imprisoned for ten years, his longest sentence and one that was expected to keep him in jail for the rest of his life.

But Gibson managed to outlast the sentence and returned to Australia after his release. He died in Brisbane in 1952. At that time, he was married to Bessie, a 58-year-old widow, and went by the name of Walter Thomas Porriott. He was 82, but claimed to be 59. He was so reviled by Bessie’s family that the couple’s headstone reads only “Bessie, died 25th June 1957, and her husband.”

A detailed examination of Gibson’s officially registered aliases may provide insight into his character, or lack of it. While in San Quentin, Gibson claimed to be from Canada. His birthplace has been variously marked as Australia, England and Canada – never where he was, always where he had most recently been, even when he returned to his home country. This suggests that, for Gibson, to move from one place to another was to wipe the slate clean, to start over, with his last port of call the only reference to his past.

Gibson travelled light. People and places were tools he obtained, used and then discarded in the acquisition of new tools. He was a predator, preying on the kindness and weakness of others. Like a shark, he probably found movement a necessary condition of existence. For someone who married so many women and spent so much time on the run, perhaps it was the only condition.

Stanton as Dr. Henry Westwood Cooper Knew It

When fraud artist Andrew John Gibson, aka Dr. Henry Westwood Cooper, arrived in Stanton in 1897, the village on the Sixth Line of Mulmur, now Airport Road, was not the quiet crossroads it is today.

As the land beyond Stanton opened for settlement in the 19th century, the village became something of a gateway to points north, a welcome stopping place for weary settlers and travellers trekking through on foot or behind a yoke of oxen.

By 1870 the bustling community boasted a school, an Orange Lodge, two hotels, a post office and several other businesses and stores (including the general store, still operating as The Olde Stanton Store, a gift and home décor emporium). But the prize that trumpeted Stanton’s status as an up-and-coming centre was the 3rd Division Courthouse, which was built in the village after fire destroyed the courthouse in nearby Mulmur Corners.

Much farther west, though, another event was signalling the beginning of the end of Stanton and many other busy early communities. The highly anticipated Toronto, Grey and Bruce Railway was being pushed through the bush, and those centres on the rail line, such as Orangeville and Shelburne, were looking forward to growth and prosperity. Not so the communities that had been bypassed.

The temperance movement also played a part. As people embraced temperance, they stopped frequenting the wayside inns and taverns that had sprung up in the early days of settlement. The Stanton Hotel, at the northwest corner of Five Sideroad and Airport Road, was one such enterprise. Today it is among the very few such buildings still standing; however, despite a dedicated community effort to save and restore it, its fate remains uncertain [see “Historic Hills” spring ’12].

Still, in 1897, the village was hanging on. But the closing of the Stanton post office after rural mail delivery was introduced gave local residents another reason not to make regular trips to the village. And as motor vehicles became more common, travel to larger centres for entertainment and supplies became easier and faster.

Finally, the prized courthouse was closed in the 1920s and relocated to Shelburne. Stanton’s heyday was well and truly past.