The Wreck at Horseshoe Curve

A famous railroad engineering design in Caledon Township became the site of a disaster on a September morning in 1907.

Like any 14-year-old old, Norman Tucker didn’t much care for getting up early. That’s why his family couldn’t hide the smiles on the morning of September 3, 1907, for he was dressed and eager long before the sun came up. Norman was going to Toronto. To the Exhibition. In his imagination he was already at the top of the roller coaster and tasting the cotton candy for sale just inside the Prince’s Gates. The Tuckers’ neighbours were amused too when they saw Norman heading over to the railway station. They’d rarely seen so much energy from him this early in the morning. Sadly, it was the last time they’d ever see him alive.

There were others at the station in Flesherton when Norman got there, all waiting for the CPR Exhibition Special out of Markdale, and everyone was happy to see engine #555 glide alongside the passenger dock, pulling a mail/smoker and three passenger cars. Norman got on the third car.

The Special was behind schedule when it got to Orangeville and was delayed even further while three more cars were added, filled with 150 passengers. But nobody complained to the conductor, Matt Grimes. They were going to the Ex and they were happy!

Matt must have been grateful for the good humour because there would be another slowdown about 20 minutes ahead so the train could negotiate the famous Horseshoe Curve in the Caledon hills, and then another stop in Bolton. But after that it was straight on to Toronto and a day of excitement, so when engineer George Hodge pulled the whistle cord twice and eased the train out of the Orangeville station, Matt could see nothing but smiles in the six passenger cars.

Uneasy feelings

He couldn’t see into the cab of #555 though, where fireman James Ross wasn’t smiling as they approached the Horseshoe Curve. He was watching the engineer. Unprofessional perhaps, but he couldn’t help himself. Engineer Hodge had run a passenger train only once before and not on this line. Besides which, James Ross didn’t have a good feeling about #555. Nobody did. Trainmen didn’t like her and called her a “roller” and “unfit.”

Just behind the cab in the smoker, some passengers too were a bit uneasy. Jim Banks from Perm looked around fruitlessly for something to hang on to for as John Thurston of Walter’s Falls said to him, the train was “goin’ an awful lick.” Those words were to be his last.

Farther back in the fifth car, the increasing sway made Rob Jelly from Shelburne crowd in closer to his wife and baby. (When the crash came, the baby would shoot through the window but all three Jellys survived.) Meanwhile in car three, true to his teenage years, Norman Tucker was thrilled by the speed, and when Mrs Sharpe of Dundalk noticed kerosene threatening to slop out of a lamp above her and moved to a different seat, he slid into her spot.

Was #555 speeding?

Was the CPR Special rolling above the mandated 25 mph safety limit when it entered the Horseshoe Curve? The Orangeville Sun two days later reported a speed of between 50 and 60 mph. Testimony from passengers at the coroner’s inquest included descriptions such as “greased lightning,” “fastest I was ever on” and “no brakes were applied.” A rail crew working at the head of the curve actually jumped the fence as the train approached. Yet Engineer Hodge – whose ability and character were strongly attested to at the inquest – insisted he had shut off steam and applied the brakes. And that his train was moving under the recommended speed.

Wherever the truth lies, several facts are indisputable. Instead of turning into the Horseshoe Curve, #555 left the tracks and travelled in a straight line for over 100 feet (30.5 m). The smoker and first four cars rolled and were smashed – reports described them as “kindling” – while the two end cars stayed on the tracks. Seven people died and 114 were injured. It was a major disaster.

Rescue and aftermath

Response from the community was swift. Rescuers showed up from every direction. Dr. McFayden from Caledon East was among the first to arrive and organized triage. The CPR hastily assembled a special train to take the seriously injured to Toronto Western Hospital. Mildly injured passengers were taken to the homes of neighbouring farmers while the uninjured tore away at the mess pulling both friends and strangers to safety.

For some it was too late. Reeve Armstrong of Orangeville, who had been in the sixth car, found a jack and levered wreckage off a man pinned under the smoker. Jim Banks weakly lifted his hand in gratitude and died. Another victim, clearly beyond saving, lay a few feet from the smoker, unidentified until one of the rescuers was horrified to recognize his own brother, Robert Carr, from Shelburne. Mrs. Sharpe, meanwhile, was inconsolable. She was only mildly bruised but had just seen the body of the teenage boy who had taken her seat.

By today’s standards, the legal machinery moved like lightning after the crash. Within days a coroner’s inquest in Brampton led to the arrest of Conductor Grimes and Engineer Hodge on charges of negligence. But just two months on, after hearing extensive testimony, a jury returned a verdict of not guilty (to loud applause in the courtroom). The CPR meanwhile cleared the last civil suit only 14 months later.

Where does the blame lie?

Simple logic forces the conclusion that the train was going too fast. So if the engineer had shut off steam and applied the brakes as he claimed, was it equipment failure? Possibly, for an inspection at the crash site reported one brake shoe missing (although Hodge testified that the brakes were working in Orangeville). The track was inspected and declared up to standard, so was the Horseshoe Curve at fault? It was an unusual, even radical design, with a reputation for minor accidents. Ultimately, no final cause was ever determined. One outcome, however, was certain. The wreck was a death knell for both the Horseshoe Curve and the Bolton-Orangeville track. In no time at all the CPR rerouted traffic to another line.

Meanwhile, as the legal and corporate machinery moved ahead, the victims’ families coped with their sorrow, although Norman Tucker’s family had one more blow to endure. The coffin delivering the teenage boy who had boarded with such enthusiasm on the day of the crash held the wrong body.

A triumph or a disaster?

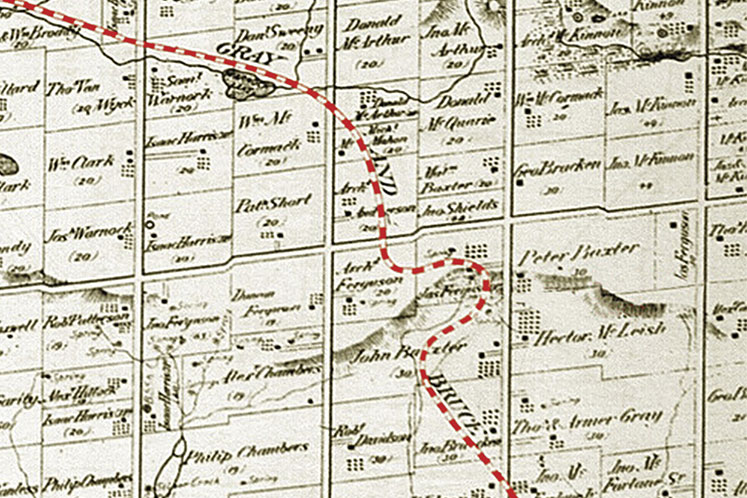

In 1870, when the Toronto, Grey and Bruce (folded into the CPR in 1884), built its way from Toronto to Cardwell Junction, near Caledon East, the line had climbed 221 metres above Lake Ontario. In the next 10 kilometres en route to Orangeville, it had to get up another 118 metres. Close to today’s Horseshoe Hill Road and Escarpment Sideroad, Chief Engineer Edward Wragge built the Horseshoe Curve, a climb of 26 metres to cover 402 metres of straight-line distance. The curve was regarded, then and now, as a significant engineering feat (and led to a popular joke that the TG&B would rather go around a stump than remove it!).

The wreck at Horseshoe Curve was far from the first setback on this accident-prone line but it was the worst. When the CPR abandoned the line it sold rights of way at one dollar per farm and gradually took out the track. On the day the last steel was torn up in 1933, a locomotive killed a bystander just down the line at Mono Road.

Related Stories

Bad Night on Caledon Mountain

Jun 20, 2008 | | Back IssuesOn a cold, dark November night in 1941, just when the war news from Europe was bleaker than ever, a fatal plane crash in Caledon Township showed that even training for war was perilous.

Two Little Railways Made North American History

Mar 23, 2008 | | HeritageThe Toronto Grey & Bruce and the Toronto & Nipissing Railways were the first of their kind on the continent.

The Grand River – When Your Neighbour is a River

Jun 20, 2016 | | Historic HillsNot only does the Grand River lay out nature’s beauty, it also offers opportunities for recreation, commerce and development. Yet all this comes at a cost, for the Grand can be both friend and foe.

Dealing with a Nightmare: The 1947 Palgrave Fire

Sep 13, 2012 | | Autumn 2012In the days before modern firefighting, nothing frightened a small community – or pulled it together more powerfully – than a major blaze. The 1947 Palgrave fire was one such case.