A Foraged Feast

Skip the supermarket, find the ingredients for gourmet dining in forest, field and stream.

Kevin Brunner boils down maple sap the traditional way at Beaverwood Farm. Photo by Don Scallen.

On a crisp morning in early April, Kevin Brunner of Beaverwood Farm in rural Hillsburgh looks as if he’s wandered off the set of The Red Green Show. He wears rubber boots, brown overalls and a plaid shirt. His bearded face is topped with a plaid hunting cap, ear flaps pinned to the sides. Unlike Red Green though, Kevin knows what he’s doing, and on this day he’s making maple syrup.

Owner and principal furniture maker of Lone Pine Furniture, Kevin is dedicated to traditional tools and methods. He takes the time to do things right. This credo informs his hobbies as well. He will spend eight to 10 hours tending the steaming cauldron over a roaring fire. This is the time needed to render 60 litres of fresh sap into 1.5 litres of maple syrup.

Kevin doesn’t produce maple syrup to make money. He taps only a dozen or so trees a year, for heaven’s sake, and his annual production averages a mere 14 litres. For Kevin, maple sugaring is a tribute to the delight he felt as a youngster in Hudson, Quebec, dipping a finger into maple syrup produced by “Uncle Phil,” his neighbour and godfather.

“Every spring Uncle Phil would sit on his patio, boil down small batches of sap on an open fire and play his banjo – music that promised a sweet reward,” says Kevin.

Admittedly, my visit to Kevin at Beaverwood Farm, an equestrian training and boarding facility, had a covetous motive. Yes, I did want to observe the process of making the syrup, but I also hoped to walk away with a jar of the precious elixir at the end of the day. This would be the first component of a wild-foraged meal I would serve to friends later in the spring. (Thankfully, Kevin did grace me with a jar!)

The Rules of the Game

My idea for this meal was loosely based on a project author Michael Pollan wrote about in his book The Omnivore’s Dilemma. Pollan prepared a grand feast out of foods gathered entirely from the wild. My meal would not be nearly as ambitious. Pollan, for example, shot and butchered a wild boar to provide the meat for the table. I had no intention of doing that, even if I could find a wild boar in Headwaters!

In creating his meal, Pollan was guided by six self-imposed rules that I decided should also guide me – with some exceptions. His primary rule? “Everything on the menu must have been hunted, gathered, or grown by me.”

I was true to this one except for cheating on essentials such as garlic and dairy products. I also added cultivated potatoes to my wild leek soup and diverged on the alcohol, serving wine from the liquor store.

The difficulty of quickly assembling all the components of my meal caused me to modify another of Pollan’s rules: “Everything served must be in season and fresh.” Instead, my meal became a homage to spring, with food gathered throughout the season.

As plants and fungi sprouted and berries ripened, I harvested them, often leaning on friends to help me out. I returned to Beaverwood Farm, for example, to pick fiddleheads with Kevin as they emerged from their wetland soils. These, along with wild asparagus, were blanched and frozen. Morel mushrooms collected in May were lightly sautéed and freeze dried. Closer to the feast in late June, strawberries and wildflowers were harvested.

This story is about the how, the why and, importantly, the ethics of gathering the wild foods for that feast.

Nutrient Powerhouses

Foraging plants for my meal led me to Karen Stephenson, creator of a website called Edible Wild Food and a sought-after wild-food educator. Karen leads walks and gives presentations that explore the food potential of the wild plants around us. When I ask her why she eats wild-foraged plants, she says, “I do this for my health. It is mind-boggling how loaded these plants are with nutrients.”

Botanist and writer John Kallas agrees. In his book Edible Wild Plants, Kallas touts wild-foraged greens as “nutrient powerhouses.” He cites studies concluding that some abundant weeds, including garlic mustard, dandelion and wild spinach, “may be the most nutrient-dense leafy greens ever analyzed.”

Kallas acknowledges you can “greatly improve the quality of your diet just by eating plenty of store-bought, dark-green leafy greens like kale, collards, turnip leaves and spinach.” But he stresses you can do yourself even more good by adding wild spinach, field mustard, dandelions, purslane and other wild foods. These wild greens, he writes, “add tremendous diversity to the diet in terms of flavours, nutrients and phytochemicals. Health benefits build through this diversity.” (Phytochemicals, also known as antioxidants or flavonoids, are compounds produced by plants and may include beta carotene and lutein.)

Both Kallas and Karen Stephenson also laud the economy of wild-foraged plants. That they are free should appeal to anyone on a tight budget. “The use of easily accessible edible weeds can spare your money for other things and expand the variety of your diet,” writes Kallas.

I used two of these “easily accessible” weeds in my salad, the foundation of which was wild spinach, or lamb’s quarters. Before reading Kallas’s book, I treated this weed like, well, a weed, pulling it and tossing it onto my compost pile. Wild spinach, like so many weeds, is a rampant grower. Clear a patch of ground and chances are it will appear. Its taste is mild, not unlike store-bought spinach.

To the wild spinach I added a handful or two of oxalis. This weed, with clover-like leaves and pretty yellow flowers, has long existed in the rather fuzzy periphery of my attention and, before my epiphany, was one I yanked out and discarded along with the wild spinach. Its tart leaves added a delightful accent to my salad.

The appellation “weed” does plants like oxalis and wild spinach a disservice. An oft-cited quote by Ralph Waldo Emerson is relevant here: “What is a weed? A plant whose virtues have not yet been discovered.”

Common Sense First

If plants have hidden virtues, they may also have hidden perils. A caveat or two about the safety of eating wild-foraged plants and other foods should be mentioned. Let common sense prevail and don’t eat anything you can’t identify with 100 per cent certainty. Karen states emphatically, “If you have even a tiny element of doubt, don’t eat it!” If you decide to forage, using a good field guide to identify the plants is essential. (See resources sidebar on page 61.)

But even after identifying a plant with certainty, Karen recommends taking a further safety precaution before you eat it. Rub a little of the juice of the plant on your forearm and wait half an hour to see how your skin reacts. The wild plants she and Kallas celebrate are as safe to eat as store-bought foods, perhaps even safer because of the lack of pesticide residues. But everyone has a unique health profile that can include food sensitivities.

Another concern when collecting wild foods is sustainability. There are lots of us, and natural space and resources are finite. Should we be out foraging at all? This question demands an answer, but I’ll start by being wishy-washy: It depends.

Wild plants range along a continuum, from “weeds” that can be gathered in any quantity to those that we shouldn’t harvest at all. Kallas’s Edible Wild Plants and Karen’s website feature a great diversity of “weeds” that pop up (and I use the term “pop-up” in the most literal sense) abundantly in human-modified landscapes: our villages, towns, roadsides and farms. They are fast-growing, profuse seeders that can easily withstand an army of foragers. Cutting off their heads may simply encourage them to sprout more, like the Hydra of Greek mythology.

But harvesting foods like fiddleheads – glorious sautéed in garlic and olive oil – merits more careful consideration. Fiddleheads, the compact leaf spirals that emerge from the ground in early spring, can be sustainably harvested by taking only two or three from each fern. If this basic rule is followed, fiddleheads can be harvested in an area indefinitely.

Some plants, however, should be harvested only in small numbers, or not at all. Ramps or wild leeks have been overharvested, which forces me to come clean about how wild leek soup ended up as part of my wild foods meal. The leeks I harvested came from my suburban backyard. They arrived in my yard unbeknownst to me, stowaways in the soil around some trilliums and jack-in-the-pulpits I had dug as part of an organized wildflower rescue in a woodland awaiting the bulldozer. For decades, these leeks have thrived in my shady woodland garden.

The recommended sustainable annual harvest of wild leeks from any given area is a mere 5 to 15 per cent. But this presumes you have a place to harvest them, and this presumption leads to another ethical consideration of wild foraging: Where to do it.

Provincial parks and conservation areas are off limits. Obviously, harvesting on private property, without permission, is an absolute non-starter. Where, then, can wild foods be ethically harvested? Start with your own yard if you have one. You can grow edible weeds such as ferns for fiddleheads, and if you have an ethical source, plants like wild leeks. Or you can take a more laissez-faire approach, loosen the landscape reins, and let some “weeds” arise in a corner.

But to broaden your selection of wild-foraged foods, my best advice is to cultivate friendships. Then join your friends in an enjoyable and sustainable harvest on their properties. I’m indebted to friends for the morels, the wild asparagus, the fiddleheads, the strawberries and, of course, the maple syrup that became part of my memorable meal.

Roads Less Travelled

Karen suggests other places to forage. Organic farmers may welcome the pesticide-free removal of “weeds” on their farms, for example. She also views the margins of less travelled roads as potential foraging grounds. “Forage at least 10 feet back of the road,” she advises, “and avoid foraging in low-lying areas where pollutants can accumulate.”

Along with the abundant “weeds,” many other wild foods can also be harvested with a clear conscience. Nuts, berries and fruit fall into this category. One of the joys of a walk in the woods is encountering ripe raspberries and strawberries.

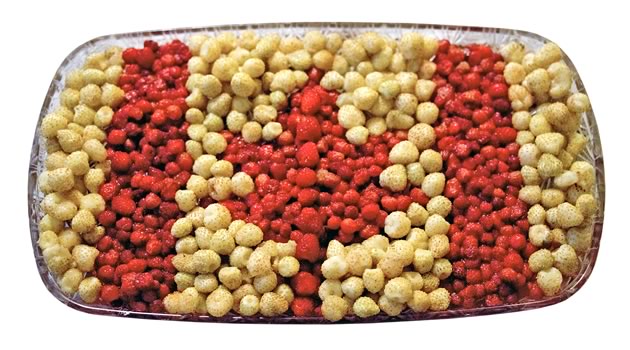

My dessert featured strawberries sweetened with Kevin Brunner’s maple syrup. The strawberries were another contribution from Beaverwood Farm, where they were gathered along a sunlit roadside verge, and included a quart of fully ripe white strawberries, every bit as tasty as the standard red. Fiona Reid, an artist friend and guest at my wild-foraged meal on June 30, used these berries to fashion a Canadian flag in honour of Canada Day.

A Canada Day presentation of wild white and red strawberries. Photo by Pete Paterson.

Mushrooms can also be gathered with few ethical qualms. Picking a mushroom is akin to picking an apple. Like an apple, the mushroom is the fruiting body of a much larger organism, an extensive fungal body that lies hidden from view in soil or wood.

The spores of a mushroom are analogous to the seeds of a fruit, and following some simple guidelines helps spread the spores to ensure future mushroom crops. First, don’t collect all the mushrooms you see. Second, hit them (this aggressive advice is from Karen – hitting helps spread the spores), and third, collect them in a mesh bag that allows the spores to disperse as you hike through the woods.

If we can set aside ethical qualms about mushroom foraging, we can’t be nearly as sanguine about safety concerns. Some mushrooms are killers, plain and simple. Remember Karen’s warning: “If you have even a tiny element of doubt, don’t eat it.”

This warning has guided my mushroom foraging over the years. I eat only a few species, those I can identify unequivocally. These include morels, which are quite distinctive and sublimely edible.

In this area morels appear in May. Hiding among the leaves and wildflowers on the forest floor, they can be difficult to find. Some people have the knack. I don’t. As a balm to my ego, my excuse is that I’m distracted by the explosion of life – the birds, butterflies and wildflowers – in the verdant spring woodlands where morels grow.

Morels are so prized that even friends are sometimes loath to divulge their locations, secrecy that can be forgiven as long as the friends are willing to share the harvest. Some of the morels I served were gifted to me, but their origins remained intentionally obscured. Other morels came from Dan MacNeal, a naturalist friend whose daughter discovered them, not in the deep, dark woods, but alongside their driveway in rural Erin.

This serendipitous bounty was quickly consumed by Dan and his family, but he graciously invited me out to look for more. I wandered with him along a woodland path. As usual, the morels had no intention of revealing themselves to me. They jumped out at Dan, however. He stopped, indicated the treasured fungi grew nearby and invited me to look. I squinted, scanned the ground, and finally saw them, poking up among mosses and tree seedlings.

The Meat of the Matter

I’m an omnivore and so too were the guests I invited, so I decided to include meat in my wild-foraged meal. Following Michael Pollan’s lead, I intended to be an active participant in the killing of the animal that would become part of the feast.

I believe anyone who eats meat should be willing, at least conceptually, to kill the animals that provide it. Being prepared to kill the animal that nourishes you forces a humble recognition of its sacrifice.

I had two choices. Hunting or fishing. If hunting, I’d be restricted to turkey, the only animal that can be hunted in spring. But I quickly dismissed the notion of acquiring my meat this way. Moral opposition wasn’t the reason. I’m not anti-hunting, as long as it is conducted sustainably and by the book. I find it disingenuous that people who speak out against hunting see no hypocrisy in sitting down to a meal of steak, chicken or pork from animals slaughtered in modern food production facilities.

Having said this, however, I’m not a hunter. I don’t own a gun. Heck, I don’t even know how to shoot one. Where to hunt would be another hurdle and, of course, I’d have no guarantee of success, especially as a complete greenhorn. And truth be told, if the opportunity to pull the trigger presented itself, I really wondered if, despite my views, I could do it.

So that left fishing. Even this wasn’t as easy as I expected. Harvesting trout, for example, is not allowed in much of Headwaters. Catch and release is the expectation. I did do some fishing at Pine River Provincial Fishing Area in Mulmur, but the one eight-inch rainbow trout I caught could hardly serve as a meal for six. Because I had left this important part of food collection to the last, I decided to visit a commercial trout farm south of Shelburne. I would have preferred wild-caught fish, but mealtime was drawing near.

I was intent on killing my fish as quickly and humanely as possible. Years ago, as an occasional angler, I would simply leave the fish on a stringer in the water until they suffocated, a practice that allows the angler a certain evasion of responsibility. So I went online and decided to follow the advice of the Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals on how best to kill a fish: a blow to the head, just above the eyes, immediately after landing it. This is how I dispatched the three rainbow trout that became part of my meal.

I found this unpleasant, but a necessary jolt of reality. Many of us think little or not at all about the origins of our food and the often unpleasant history of its journey from farm or sea to plate. Killing the trout encouraged me to be mindful of the deaths of all the store-bought salmon and halibut that sustain me over the course of a year.

Navigating ethical issues like this and others relating to the collection of wild foods can give us greater insight into our relationship with food in general. Pollan writes that foraging and hunting enabled him to better understand the ecology and ethics of eating in a way he could not get in a supermarket or fast-food chain or even on a farm.

Pollan also writes, “Foraging for wild plants and animals is, after all, the way the human species has fed itself for 99 per cent of its time on earth; this is precisely the food chain natural selection designed us for.” There is an elemental goodness about foraging, a rightness etched in our DNA.

And aside from the gravity of taking an animal’s life, the process of planning a foraging session and searching for and preparing wild food has great appeal, especially when shared with friends and family. Kevin Brunner, channelling Red Green, knows this. Producing maple syrup forged a bond with his beloved godfather many years ago. Kevin now gathers friends and family around his steaming syrup kettle and forages with them at Beaverwood Farm for fiddleheads, wild asparagus and strawberries.

There is an adventuresome, self-reliant joy in this, as well as exercise and plenty of fresh air.

And of course, in the end there is the eating – in my case, the eating of delicious foods gathered from the good earth of Headwaters, prepared with care and served to dear friends. Friends who, by all accounts, enjoyed the meal, the happy culmination of my season-long quest for wild foods.

Dinner is served – (left to right) Don Scallen with guests Peggy Stansfield, Fiona Reid, Nikki Pineau and Joseph Bryson. Photo by Pete Paterson.

Foraged finds from left to right : Oxalis greens (top left) and black raspberries; wild leeks, morel mushrooms and fiddleheads; wild asparagus; fiddleheads; rainbow trout; daylily petals (top right) and wild spinach, also known as lamb’s quarters. inset : Wild spinach salad

A Wild Menu

Salad

Freshly foraged baby wild spinach and oxalis greens accented with day lily petals and black raspberries.

Soup

Wild leek and potato garnished with flowering raspberry blossoms and wild leek flowers. (See recipe)

Vegetables

Steamed wild asparagus and Beaverwood Farm fiddleheads paired with select wild leeks sautéed in virgin olive oil.

Mushrooms

Morels sliced lengthwise and gently sautéed in garlic and butter.

Meat

Pan-fried rainbow trout, locally sourced, drizzled with Beaverwood Farm maple syrup.

Dessert

Wild white and red strawberries sweetened with Beaverwood Farm maple syrup.

Beverage

Pineapple weed tea, lightly steeped. (See recipe and instructions)

More Info

Some resources before you set out

Pick up a book, visit a web site or attend a walk on the wild side.

| Edible and Medicinal Mushrooms of New England and Eastern Canada

by David L. Spahr (North Atlantic Books, 2009) Excellent descriptions of edible mushrooms along with comprehensive advice on how to find them and prepare them for eating. |

|

| Edible Wild Plants: Wild Foods from Dirt to Plate

by John Kallas (Gibbs Smith, 2010) For my money, the best wild plant-foraging book, filled with valuable information about all aspects of plant foraging and meal preparation. Includes excellent diagnostic pictures of many common edible “weeds.” |

|

| Newcomb’s Wildflower Guide

by Lawrence Newcomb (Little, Brown, 1989) |

|

| National Audubon Society Field Guide to North American Wildflowers: Eastern Region – Revised Edition

by National Audubon Society (Knopf, 2001) |

|

| The Omnivore’s Dilemma: A Natural History of Four Meals

by Michael Pollan (Penguin, 2006) A beautifully written contemplation of our relationship with food in the modern era, it includes Pollan’s account of the wild-foraged meal that inspired mine. |

|

| Edible Wild Food

Karen Stephenson’s website provides a wealth of information about edible wild plants and how they can benefit your health. |

Walk on the edible wild side with Karen Stephenson

Explore the edible wild side with Karen Stephenson at Simcoe County Forest’s Wallwin Tract at 10 a.m. on Saturday, June 4. Organized jointly by Dufferin and Simcoe County Forests and Dufferin Simcoe Land Stewardship Network, this walk and workshop focuses on the edible and medicinal values of various wild plants.

The Wallwin Tract is located near Everett at 6600 Concession Road 4, Adjala- Tosorontio. Cost is $20. Pre-registration is required. Contact Caroline Mach, Dufferin County Forest manager, at [email protected] or at 519-941-1114 ex.4011.

Related Recipes

Pineapple Weed Tea

Mar 21, 2016 | | DrinksPineapple Weed is a member of the aster family, it is easily overlooked because it lacks petals.

Wild Leek Soup

Mar 21, 2016 | | SoupsPlease harvest wild leeks sustainably, taking only 5 to 15 per cent of a given population a year.