Tracking 101

It’s not just the tracks, but the story they tell.

Dusted by occasional snow flurries, outdoor educator Alexis Burnett, along with four tracking apprentices, gathered at the foot of Old Baldy, a rocky cliff jutting out of the Niagara Escarpment just south of Kimberley. I had been invited along to learn something about the art of tracking.

Alexis readied us for adventure. He knew lots of tracks would inscribe the snow that blanketed the woodland. Our goal was to identify the creator of those tracks, but Alexis encouraged us to go beyond mere identification to glean clues about the behaviour of the birds and animals that made them.

The temperature was –6°C, but an approaching high pressure system would see it drop to -12 later in the afternoon. No matter, Alexis’s tracking style is decidedly active. We wouldn’t be cold.

Outdoor educator Alexis Burnett says tracks provide clues to animal behaviour. Courtesy Earth Tracks.

As our search began I was reminded again of the quiet that reigns in our winter woods. To be sure, there is sound, but it is usually sporadic: the shrill cries of blue jays, the “yank, yank” notes of foraging nuthatches, the cawing of crows or the chatter of chickadee troupes bustling through the trees. But the overwhelming impression is quietude. This scarcity of sound may lead some to conclude that winter woods are largely bereft of life, but trackers like Alexis find its signature everywhere.

A secret city

A ruffed grouse made its own snow angel. Photo by Robert McCaw.

The winter woodland is a secret city, populated by creatures adept at concealment, active mainly after the sun sets. There is drama in this city, with animals and birds engaged in life-and-death struggles. The hunted among them slink and scurry, driven by the imperative to eat, while the hunters look and listen, alert to the sound of teeth gnawing on bark or a glimpse of furtive movement in the moonlight.

On this day, with the occasional cronk of ravens overhead, we found plenty of evidence of hidden life. We saw no deer, but their tracks were common. We found where some of them had bedded down in copses of cedars. There, encouraged by my smiling companions, I knelt down to smell deer pee. A revelation. As they had promised, the scent was pleasantly spicy, the distilled essence of cedar and balsam fir.

Where deer abound in a healthy ecosystem, their predators do too, so we saw plenty of coyote tracks. Turkeys, ruffed grouse, weasels, squirrels and cottontails left their marks in the snow as well. The widely separated tracks of a bounding snowshoe hare spoke of fear. Spooked by something, it had darted toward the safety of a thicket.

Alexis led us up to the base of the cliff where we found that a heavy, low-slung animal had ploughed through the snow. A porcupine. These plodding rodents, protected by their passive weaponry of quills, find refuge in the numerous cracks and crannies of the escarpment cliffs. They are common forest dwellers in southern Ontario and for decades enjoyed a porcupine Shangri-La, chomping tree bark to their heart’s content and bothered only infrequently by the occasional hungry or misguided coyote.

The resurgent fisher

But to the north, a porcupine nemesis stirred. The fisher, a large weasel possessed of quicksilver movements and a unique porcupine-killing skill set, was on the move southward. Following their bristling quarry, fishers now hunt at least as far south as Orangeville. The porcupine’s brief tenure of peace has ended.

Fisher tracks. Courtesy Kim King.

So along the talus slope at the foot of Old Baldy, it was no great surprise to find the tracks of this resurgent predator. We found no evidence of a porcupine kill, however. Perhaps they were too well protected in their rocky retreats, forcing the versatile fisher to seek other prey. Red squirrel may have substituted for porcupine on this day. We found the remains of one – little was left but the squirrel’s bushy tail.

Alexis loves the life that abounds in our fields, forests and wetlands. An Orangeville upbringing and parents who were enthusiastic naturalists gave him plenty of opportunity to nurture his passion. In his youth he would ride his bike to special places along the nearby Niagara Escarpment. Mono Cliffs Provincial Park was a favourite destination.

Over time, he developed a keen interest in tracking and now, at 37, he operates Earth Tracks Outdoor School and Wilderness Canoe Trips, which offers courses to teach others the art of tracking. “Learning to track has been a beautiful part of my growth as a human being,” he says.

Tracking in its basic form is simply identifying and following animals. But for Alexis that is just the beginning. “It’s not just about tracks, but about the behaviour, habits and movements of the animals that made them. It’s about how animals interact not only with their own species, but also with other species and with the plants, trees and the landscape itself.” Alexis is driven to learn about ecological links and connections directly from the animals.

A vole’s tracks ended suddenly when it made a meal for a hawk or an owl. Photo by Robert McCaw.

He moves purposefully through a landscape and, though always on the lookout for tracks, is keen to observe anything else – such as feathers, scat, broken branches and chew marks on branches – that may help him flesh out the ecological connections he seeks. Tracking with Alexis at Kinghurst Forest in Grey County, for example, we followed a deer trail and discovered where the deer stooped to squeeze under a fallen tree. Demonstrating the attention to detail that is a hallmark of good tracking, Alexis reached down and recovered a strand of hair snagged by the tree’s bark. He showed us how it kinked when bent, an identifying characteristic of the hollow hair of deer.

Purposeful listening

Alexis also pays attention to sound in the woods, especially bird calls. Listening to birds can provide clues to the unfolding dramas of the woodland. This demands expertise – knowing the species that is calling and, more challenging, interpreting their messages.

A famous example of people tapping into bird communication is found in Africa. There, the fabled honeyguide birds seek out people and lead them to beehives, in return for access to honey and larval bees. Remarkably, the communication is sometimes reciprocated. Their human benefactors apparently summon the honeyguides to accompany them on honey hunts as well.

Here in North America, ravens will advertise the location of a dead animal with a tumult of discordant calls, a cacophony Alexis tunes into when he is in the field. Like honeyguides, ravens may be requesting help to access a resource. Wolves, coyotes and other predators can open up a carcass allowing the ravens to feast.

Birds make alarm calls that ripple out from the position of a predator – a fox or weasel, perhaps – telling the wildlife community, and the savvy tracker, of the predator’s location. Trackers able to interpret this language can use it to guess what the predator is.

Alarm calls that shout “Weasel!” are random, because weasels often move about in an unpredictable manner. But foxes and coyotes tend to travel in relatively straight paths, causing a “popcorn” alarm sequence according to Jon Young in What the Robin Knows. As a fox moves along a hedgerow, for example, birds will “pop” up and voice alarms along its route.

Storymaking

Tracking, then, is more than simply following the footprints of animals. It is careful examination of other visual evidence and an awareness of the meaning of bird and animal vocalizations. With attention to details like these, predictions can be made, scenarios imagined, speculation proffered and credible stories constructed. The storymaking – the building of meaning – is one of the goals of tracking.

In fact, tracking may have helped make humans the storytelling animals that we are. Louis Liebenberg, author of The Art of Tracking: The Origin of Science, writes, “Hunter-gatherers share their knowledge with each other in storytelling around the campfire. [They] take great delight in lengthy, detailed and very gripping narrations of events they have experienced.”

Alexis has plenty of tales to tell around the campfire. He told me one about a tracking expedition he led in Algonquin Park. “We followed a grouse through a forested area with balsam fir and hemlock, and all of a sudden came upon the bounding, two-by-two tracks of a marten that had intercepted the grouse. Marks in the snow indicated that the marten was dragging the grouse. We followed those marks to a sheltered alcove under the snow-laden boughs of a balsam fir.”

At that point, he continued, “We encountered more tracks: wolf tracks leading to the shelter. We hypothesized that the wolf took the grouse from the marten. Backtracking supported our guess. We found where the wolf had abruptly stopped and turned 90 degrees. And then headed directly to the balsam fir and to the marten and the grouse. The next day, about a mile away, we came across a fresh pile of wolf scat. We poked around and a grouse foot emerged. It may not have been from the same wolf, but it’s very likely that it was.”

The guesswork and hypothesizing involved in tracking has generated a fascinating proposition that the scientific method owes its origins to tracking. Liebenberg argues that “to interpret tracks and sign trackers must project themselves into the position of the animal in order to create a hypothetical explanation of what the animal was doing.” With the hypothesis formulated, the trackers would gather evidence to support or disprove it, just as scientists do today. Acting on a sound hypothesis might allow a tracker to find an animal even in the absence of well-defined tracks. Those who failed to think “scientifically” could go hungry.

As Paul Rezendes writes in Tracking and the Art of Seeing, “At one time being able to read tracks and sign was a matter of life and death. Knowing where the food was and what the predators were doing could mean the difference between survival and extinction.”

A red fox made its solitary way across a frozen landscape. Photo by Robert McCaw.

Predator and prey

On February 26 this year, shortly after Alexis introduced me to tracking, I headed to Boyne Valley Provincial Park just east of Shelburne. The crystalline splendour of the trees dazzled after an ice storm earlier that week. I was there to test my rudimentary tracking skills, think scientifically about what I found, and perhaps leave with a story or two.

The trails of many animals were etched in the snow: rabbits and mice, squirrels and shrews, and possibly minks or weasels. Sign of deer abounded. I found imprints where two deer had rested under the shelter of hemlocks. They had been feeding well – scat littered the snow.

Following one deer track I measured a series of bounds about 13 feet apart. I hypothesized that those enormous strides were powered by fear, much like the track of the snowshoe hare at Old Baldy.

Evidence of the probable source of that fear was easy to find, as coyote tracks were abundant. I pondered the relationship between coyotes and deer in our winter hills. I imagined a high-stakes chess match played out between the two species in the winter – move and countermove. With luck, fit deer avoid checkmate. A bad decision or ill health brought on by disease or old age tilts the board in the coyote’s favour.

The life-and-death struggle between deer and coyote shouldn’t be lamented. Rezendes uses the predation of moose by wolves to illustrate the benefits that accrue to both prey and predator. “Wolves continuously test the healthy and remove the weak. They shape the physical characteristics of their prey, leaving the healthier and stronger animals to breed. In turn, the moose challenge the wolves to become efficient and successful predators.” Both ultimately depend on the other for their well-being.

Rezendes sees an “essential unity” in the relationship between predator and prey. This essential unity, however, extends beyond the immediate predator and its prey to include many other creatures. In these hills, coyotes, foxes, weasels, fishers, ravens and a host of smaller creatures such as shrews, mice and chickadees feed on a deer carcass. Death begets life. Alexis refers to the sites where animals die as “wheels.” The “spokes” of these wheels, radiating outwards from the dead animal, are the tracks of the many animals that owe their lives to the deceased.

Lucky for the rabbit, only its tracks crossed paths with the fox. Photo by Robert McCaw.

A naturalist’s dilemma

As Alexis explores sites like these – in fact, whenever he does any tracking at all – he is conscious of how his presence may be affecting the animals he seeks to understand. Though he loves to get close to animals, he doesn’t want to cause them undue anxiety and agitation.

“When they’re aware of your presence,” he says, “you can see it in their behaviour, in their tracks. That’s when I say to myself, ‘enough,’ and back off. The goal is not always to see the animal. It’s a special gift when you do, especially when they are engaging in their natural patterns, but for me it’s about the journey of the learning on the trail.”

Alexis articulates a dilemma all thinking naturalists struggle with. We want to connect with nature, with animals, birds and plants, but we don’t want to hurt what we love. Respect, a key to healthy human interaction, must also prevail in our relationship with animals. My own most treasured moments with wildlife are times when the animals aren’t aware of me, when I can watch them interact naturally with their environment. Encounters like these are deeply satisfying.

And if encountering animals through outdoor pursuits like tracking is good for us, in the final analysis the animals can benefit as well. Understanding the “other,” whether among our fellow human beings or fellow animals, helps build bridges and leads us to value other lives. “Ultimately, tracking an animal makes us sensitive to it – a bond is formed, and intimacy develops,” writes Rezendes.

Alexis agrees. For him, tracking is a way to help connect people in a deep and powerful way to nature. “With tracking, you develop a real empathy for the land and for all the creatures that are out there.”

This empathy may be crucial to conservation. Liebenberg believes our estrangement from nature may be the “most dangerous threat to the survival of many species in the face of ‘advancement’ and ‘progress.’” He believes one of the most important drivers of nature conservation is the public’s general awareness of wildlife, but he also notes, “Even keen nature lovers are often unaware of the wealth of animal life around them, simply because most animals are rarely seen.”

~~~

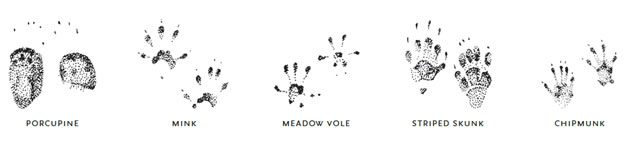

Mink

Mink are seldom seen, but these semi-aquatic animals live in almost every wetland in these hills. They are very active through the winter and leave their tracks along riverbanks and the margins of ponds and lakes. They’ll also frequently venture onto ice. A trail that ends abruptly at a hole in the ice is likely that of a mink. Their tracks are often in twos, the front feet touching the ground together, with the rear feet doing the same. But minks can leave tracks in other patterns as well.

Mink trails are fun to follow. Sometimes a mink will dive into the snow, leaving an almost circular tunnel about three inches in diameter. On streambanks, look for mink slides. Like otters, mink will slide on their bellies when slopes allow – undoubtedly an energy saver, but probably good fun as well!

Mink scat is narrow and rope-like, and even in winter reveals their aquatic foraging habits. At Forks of the Credit Provincial Park last winter, I found mink scat containing crayfish claws.

A mink, playful or hurried, took advantage of a hillside slide. Photo by Robert McCaw.

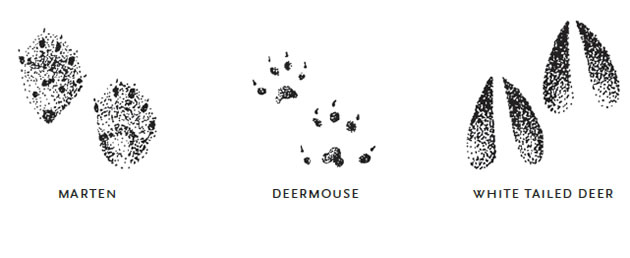

White-tailed deer

Deer are big and common, making them excellent choices for a novice tracking adventure. When you find a deer track, first determine the direction of travel. The splayed hooves of deer taper to points at the front and are rounded to the rear. The pointed ends indicate the direction.

As you follow the tracks, be on the lookout for deer sign. You’ll certainly find their scat or pellets – they look like little rounded cylinders usually less than an inch long. You may find where they have peed. If you’re brave enough, have a sniff. My guess is that, like me, you’ll find the scent pleasant!

Like us, deer need to rest, and following a trail long enough will likely lead you to a deer bed. You can examine the bed and attempt to figure out the body position of the reclining animal.

Look for signs of deer browsing as well. Because deer possess only bottom incisors, they leave rough cuts on twigs. They also scrape bark off young trees with their teeth, and in the fall, bucks will rub their antlers on saplings and trees, removing bark.

Deer made a beeline to a foraging area. Photo by Robert McCaw.

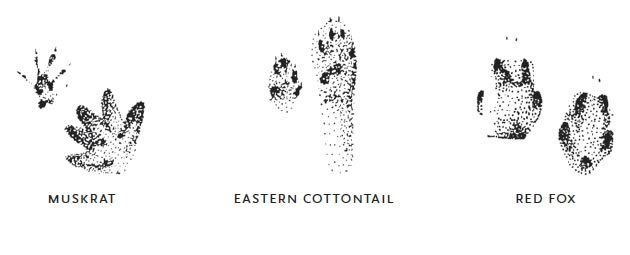

Cottontail rabbits

Anyone who has spent any time in the winter woods has likely come across the distinctive tracks of a cottontail. These form a roughly triangular pattern.

Cottontail scat is small and spherical, similar in appearance to Cocoa Puffs cereal. In winter cottontails feed primarily on the twigs of small shrubs and trees, a habit that makes them the bane of gardeners! They snip those twigs at clean 45-degree angles, in contrast to the ragged cuts made by deer.

A popular misconception is that rabbits dig holes for shelter and as dens. European rabbits do, but not North American. Instead, cottontails shelter in dense tangles above ground, and their tracks will usually lead to these protected retreats.

Cottontail rabbit tracks. Photo by Robert McCaw.

More Info

Tracking Resources

Books

Mammal Tracks & Sign: A Guide to North American Species by Mark Elbroch. Many trackers consider this award-winning book to be the best of the genre.

Tracking & the Art of Seeing: How to Read Animal Tracks and Sign by Paul Rezendes. This book served as my introduction to tracking literature. A comprehensive resource.

Animal Tracks of Ontario by Ian Sheldon. A convenient little guide to carry in your pocket on woodland rambles.

Courses

Earth Tracks founder Alexis Burnett offers a wildlife tracking apprenticeship program. One weekend a month over a period of 10 months is devoted to intensive nature study and tracking. Earth Tracks also offers a variety of other outdoor experiences and workshops. Find out more at earthtracks.ca.

Related Stories

Fishers have been Lured South

May 3, 2011 | | EnvironmentFishers are said to attack porcupines in a particularly grisly manner.

Cougar Sightings

Sep 9, 2009 | | EnvironmentThere have been cougar sightings in the area. Have you seen any? Tell us your stories.

Hi Don,

Do we have the Carolina chickadees in Adjala Tos? The American websites all claim that the hybridization line is below the great lakes. We have smaller chickadees with a short crisply ending bib at our feeder as well as the larger one with a more raggedy bib. I haven’t heard a difference in their calls as we are usually watching them at the feeder where you can compare size.

Thanks for the tracking article. I will send some pics of our tracks. Unfortunately we have had so little sun that they are not crisply clear.

Cheryl Bailey

ps what’s the latest on the meadow article? going ahead, using my meadow?

Cheryl Bailey from Adjala/Tos on Feb 5, 2017 at 9:03 pm |