Illuminating the Past: Personal History

How private archivist Alison Hird’s work is helping one family reflect on their personal history – and preserve it for the future.

The sturdy dining room table in Robin Ogilvie’s Caledon home is covered with so many old photos, family heirlooms and framed paintings you might think she was cleaning out a closet or redecorating. But this has been a common scene here for the past two years, as Robin has worked elbow to elbow with white-gloved archivist Alison Hird, poring over artifacts and refining a rich family narrative.

Robin works with archivist Alison Hird to document the Howard family heirlooms and papers in the dining room of her Caledon home. Photo by Pete Paterson.

After 12 and a half years as collections manager for Dufferin County Museum & Archives – now Museum of Dufferin – Alison started her Caledon-based company Treasured Collections in 2015 to work with private clients who want to learn more about the history lurking in neglected drawers, files and boxes. As she uncovers and documents those objects and papers, Alison’s job is to illuminate the stories behind them.

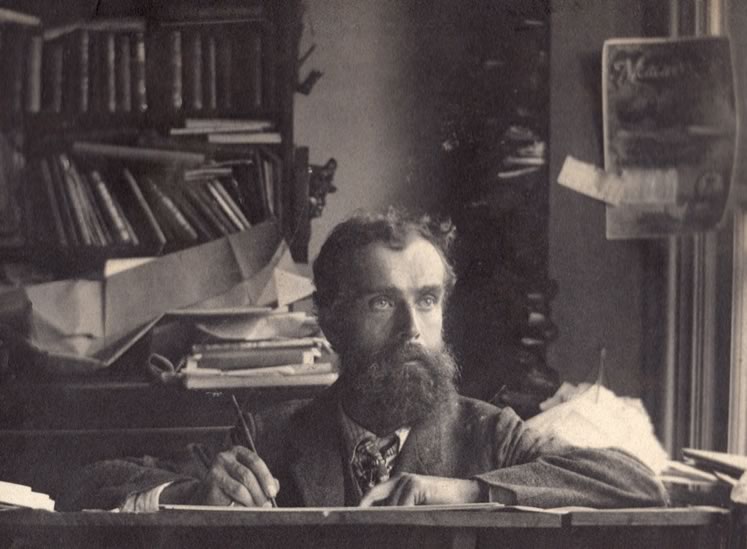

That’s an especially fitting exercise in Robin’s case, since illumination plays a significant role in her family’s story. Her great-grandfather, Liverpool-born family patriarch Alfred Harold “A.H.” Howard (1854–1916), was a graduate of the Royal College of Art in London and a well-known “illuminator.” A practitioner of what would now be called graphic design, A.H. referred to his craft many different ways at the time, as art, lithography, illumination, design and “the transfer paper method.” He advertised “illuminated addresses a specialty” on one of his business cards. Luckily, Robin, who moved to Caledon in 1996 with husband Robert and their three children, owns some exquisite examples of his work, some of which line the walls of their gracious stone home on Coffey Creek Farm where the couple raises Rocky Mountain horses and cattle.

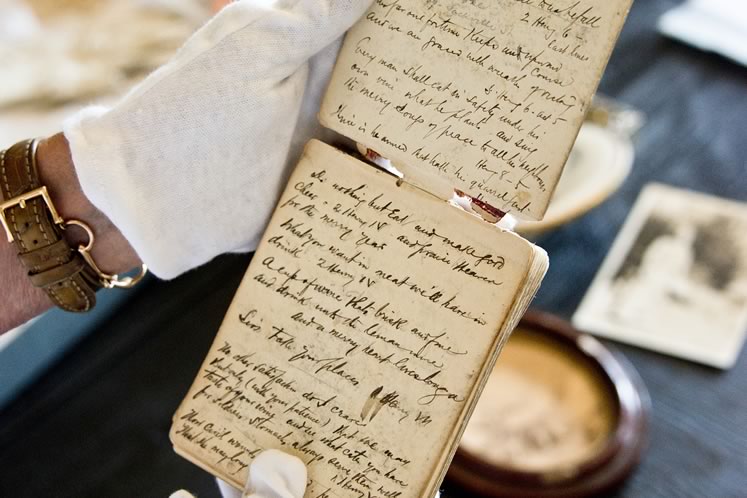

Today Alison and Robin are showing me four little brown notebooks dated from 1885 to 1889, found in the back of a cousin’s closet. Filled with A.H.’s everyday musings and sketches from his family life, they became a jumping off point when the pair embarked on their journey. Alison describes them as “delightful” as the two women gently open them up to show me during a recent visit.

It’s clear when watching the two work together that Alison and Robin share something special and speak in their own shorthand: “…because I know about the thing in the thing,” Alison will say, rooting through a storage box. “I know all her family secrets,” she adds with a conspiratorial smile.

A family archive begins

Fastidious and dedicated, Alison immigrated in 1997 to Canada from Portsmouth, England and her lingering British accent is easy on the ears. She stresses she is not a genealogist, an antiques specialist or a writer of history. “The past is already written, and the ink is dry,” as Game of Thrones author George R.R. Martin famously put it. Instead, Alison’s passion is to ignite in people the desire to take a close look at their significant family artifacts and document them for the benefit of future generations. Items that are especially delicate or precious, or those less useful or “less pleasing” to contemporary eyes, but still have a story to tell, are worth preserving and storing with care, she says.

Robin wears white gloves to handle the leather journals her great-grandfather used as diaries and sketchbooks. Photo by Pete Paterson.

Robin’s treasures will live on in two pale grey bankers boxes. In the end, members of Robin’s family, including seven grandchildren, will receive a PDF catalogue with entries for each item. Robin plans to create a commemorative hardcover book too.

For her part, Robin says Alison provided her a structure that “absolutely thrilled” her and relieved her of “a big obligation hanging over my shoulders. I couldn’t sit down and do it myself – I’m not a very organized person. I could never have organized it properly like this.”

The amount of material from A.H. is huge, and only a part of the “mishmash” of interesting pieces Robin says she inherited from her aunt and mother. Overwhelmed by such a mass of material, she only knew she “didn’t want to just leave it,” and felt obligated to organize it in some way. That’s when she saw the Treasured Collections ad in this magazine and called. After Robin confessed she didn’t know where to begin, Alison wryly advised her, “Yesterday would have been a good time to start,” and dove in. As relatives gradually got wind of the project, they donated new items too.

Alison begins by asking a client to pinpoint the oldest relative as a starting point, and to pick six to eight items of significance, which she then uses to form a through line connecting them to her client. In some lucky cases, like Robin’s, a relative will have left an impressive public record. A.H. emigrated from England to Canada in 1876 and soon won renown, especially for his hand-drawn work capturing Toronto City buildings. His designs eventually made their way to the Royal Ontario Museum, the Art Gallery of Ontario, and the National Gallery in Ottawa. Some even grace the art collection of Britain’s royal family.

Robin Ogilvie’s great-grandfather, Liverpool-born family patriarch Alfred Harold “A.H.” Howard, was a graduate of the Royal College of Art in London and a well-known “illuminator.”

A.H., however, tried out at least one other career first. In his early life in Liverpool, he dreamed of becoming an actor. One of Robin’s most amusing discoveries is a letter he wrote to his brother Jim in February 1876. In it he describes his heartbreak at an embarrassing stage performance, which was rewarded by a barrage of tomatoes. Perhaps his shame prompted him to put down new roots in Toronto and begin a business as an artist and designer.

Filling out the details

In Toronto, A.H.’s immediate family grew to include a girl and four boys, the children of his first wife and Robin’s great-grandmother Isabella Harriet Eunice Cannell (1853–1886). Unfortunately, Isabella, who came from the Isle of Man, died in childbirth in 1886 (the twin boys she gave birth to also died). Her wedding dress was donated by Robin’s family to the ROM in 1977.

The eldest son, Sidney “Sid” Harold Ross Howard, married Robin’s grandmother Isobel “Bel” Kyle in 1906. Many of the finer artifacts in Robin’s collection belonged to her (see below). Sid and Bel Howard bought a stone cottage in Caledon, where Robin has many fond memories of her youth and family gatherings. (The house was featured in the spring 2010 issue of In the Hills.)

Not all the memories Alison and Robin uncover are happy ones, however. One disturbing artifact comes from Bel’s side of the family. A mournful letter believed to have been written in 1853 by Bel’s grandmother Margaret Armstrong details the perilous cross-Atlantic journey from Scotland that took two of her children’s lives, and the lives of an aunt and uncle:

“God in his great goodness gave me strength beyond everything to bear this severe affliction but Oh! what days of fright and suffering to us. My dear boy died on the fifth morning after we set sail at four o’clock and was consigned to the deep according to the rules of the ship at eleven. My dear dear Jane survived till September 6th she never properly recovered from her sea sickness, and dysentery was the cause of her death. It had commenced upon James Thomas before we left Glasgow. I called in a doctor who prescribed for him but alas, medicine was unavailing in both cases. No doubt the disease had been increased by sea sickness setting upon us so soon, and also made more severe by the storm which overtook us the second night after we sailed. In the morning we were all laid prostrate. The storm continued for 40 hours, you may easily imagine the deplorable condition we were in.”

In a thin, hardly legible script, the letter is written both horizontally across the page and again diagonally over the primary text – a not uncommon practice in the 18th and 19th centuries to preserve postage costs. Alison was able to transcribe it and piece together information to clarify the date, although she could only guess at the signature. “Some things we’ll never know,” says Alison.

Still, Alison’s attention to detail inspires Robin’s praise. “Every time she came back things came together a bit more.”

How to store it all

As she wraps up her research on an object, Alison taps into her museum-level know-how to make sure it’s safe for years to come. The special materials used to store these artifacts are paramount to the preservation effort, she says. She recommends a selection of pH-neutral or acid-free tissues, card covers, Mylar sleeves and storage boxes. Items like leather books can mold, and archival methods can stop the mold and prevent it from spreading.

Another preservation technique is to avoid anything sticky, like glue or Scotch tape, as these can not only damage a photo or object, but can damage nearby items as well. Newspaper wrapping is verboten, as the ink can transfer and stain the object. Of course, Alison advises against storing items in damp basements or exposed to sunlight.

And resist the urge to pull out those stored objects too often, Alison says. Anything can be damaged through frequent use, so the best method of preserving your family heirlooms is to keep them boxed and packed away (unless they are in archival quality frames or a china cabinet away from sunlight). This may sound extreme, but she tells clients to pull out the PDF documentation instead when nostalgia hits.

This is not say Alison suggests treating all inherited belongings like museum pieces. By all means use your heirloom china, crystal or silverware, which she calls “stable artifacts” in archivist lingo. (Just don’t put it in the dishwasher, please and thank you.)

Most of Treasured Collection’s clients are seniors who want to reduce their belongings as they downsize to smaller accommodations. “We are living in a different society,” Alison says. Instead of passing wedding gifts down to the next generation, older generations are finding that younger folks “don’t want china or crystal because they can’t put it through the dishwasher. These things don’t have a future with the family.”

As for tossing or giving away historically significant or potentially valuable items, Alison understands necessity might render large furniture, such as grand pianos and china cabinets, obsolete. For these she advises taking photos and cataloguing the information before selling them or carting them to museums, historical societies or charity shops. But be sure to do your research. Most museums are very particular about what they will keep, she says. Donated items must be relevant to their collection policy, distinctive and preferably small.

What to keep

One series of objects Robin won’t part with are A.H.’s watercolour landscapes, which fit her home’s airy country aesthetic. As we tour a few of A.H.’s paintings on a second floor landing, Alison jokes that Robin is trying to confuse her – every time she visits, they are hung in different places.

A.H.’s designs and illuminations paid the bills, but these paintings represent his beloved pastime and they hint at his broader legacy. Many of his relatives and descendants worked in the arts as playwrights, artists, writers and actors. A.H. himself was not only an artist, he was also a renowned choir master and organ player.

Among Robin’s most cherished inherited items is a series of watercolour paintings by her great-grandfather A.H. Howard. She changes up their locations often throughout her home. Photo by Pete Paterson.

As Robin and Alison pack up for the day they reflect on how much they’ve learned about A.H. Just as his work illuminated a subject and presented it in its best light, so too has Alison illuminated A.H. and his family tree.

As the Howard family artifacts get filed away and the white gloves come off for another session, Alison looks across the dark mahogany table where she and Robin have spent so many days working and says, “It took a lot to figure out what’s what, but we got there in the end, didn’t we, Robin?”

A Closer Look

Here is a glimpse of some of the intriguing objects Alison Hird has researched and catalogued for client Robin Ogilvie.

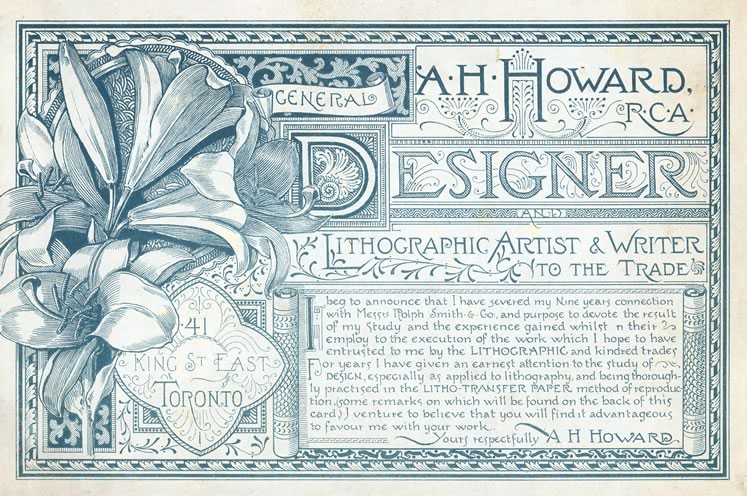

Advertisement circa 1885

- H. Howard’s business card advertised the independent lithographic company he opened on Toronto’s King Street East after nine years of partnership in an outfit called Rolph, Smith & Co. He pitches the “new” techniques used to make the card:

“For those unacquainted with the Transfer Paper method I may explain that the work is executed with Litho Ink on a coated paper, and transferred to stone in the same way as Copper plate or Stone transfers. It is better for many purposes than Stone engraving, far cheaper than Copper plate, and the work can be transmitted through the post, or otherwise conveniently carried. Both sides of this card were executed with transfer paper.”

Though he calls lithography a trade, he emphasizes his “earnest attention to the study of design,” indicating the more creative aspect of his business.

Locket circa 1912

This locket was owned by Isobel Howard and given to her by her husband around 1912. Inside it contains, unusual in locket form, a powder puff, mirror and powder. The locket is 9-karat gold and carries the hallmark of Charles S. Green & Co. of Birmingham (1905—1982). This piece was most likely designed by Charles’ wife Winifred, a talented artist who designed all the firm’s early patterns.

Card purse 1878

These double pocketed mini-purses were used by ladies to hold calling cards when visiting friends and acquaintances and to keep track of visitors they’d missed at home. The pockets on one side held the owner’s cards, to be left if a friend was not at home. The other pockets were used to store the cards collected by the owner. Because Robin’s grandparents lived on Ellis Avenue near High Park – a long journey from downtown Toronto in those days – visitors would have been more likely to call during the day, according to Alison. In the event the Howards were out, the visitor would leave a card, indicating they had paid a call and when a reciprocal visit might be suitable.

Brooch circa 1912

This amethyst and rhinestone brooch was given to Isabella Howard by A.H. Howard’s eldest son Sid around 1912. Robin Ogilvie, Isabella’s granddaughter, wore the brooch to her prom in 1960. The brooch was designed by Kandell & Marcus located at 17th Street and Broadway in Manhattan at the time.

Exciting news! Your article has prompted discovery of another “A H” artwork within the local community. I have shared the information with the Howard family decedents, and the details including an image are posted on my blog: https://www.treasuredcollections.ca/Blog/history/exciting-new-find-new-local-howard-artifact-discovered/

Alison Hird from Caledon on Dec 11, 2018 at 3:59 pm |

What a lovely story . From the tragedy of the Atlantic crossing to the superb artifacts now treasured in a perfect setting. Thank you for sharing.

Priscilla Reeve from East Garafraxa on Nov 22, 2018 at 9:37 pm |