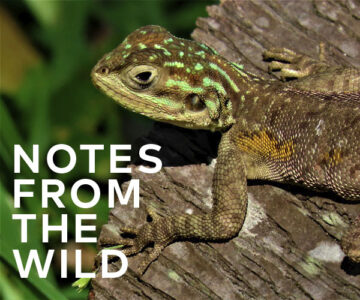

Incredible Insects

The benefits of the bugs in our backyards.

Be very glad that six-spotted tiger beetles aren’t the size of sheepdogs. These little hunters, which prowl sunlit trails throughout our hills, are predatory machines. Equipped with bulbous compound eyes and segmented antennae, they are alert to the slightest movements of their invertebrate prey. Powerful legs give them speed to burn. And their jaws! Serrated killing tools suggestive of medieval torture mechanisms. Six-spotted tiger beetles shine in iridescent green. Like their namesake tigers, they are beautiful but deadly.

A six-spotted tiger beetle. Photo by Robert Noble.

Not everyone will agree tiger beetles are beautiful. And some will find their predatory lifestyle unsettling. Many people, of course, simply don’t like insects, regardless of how the bugs make a living. Honeybees and butterflies usually get a pass, but other insects are often viewed with distaste, even revulsion. I hope, though, that learning about the vital contributions made by insects to healthy ecosystems and economies can help shift negative attitudes. And learning about their diverse forms and their wondrous ways of being should appeal to anyone with a smidgen of curiosity.

Insects at risk

Anyone with an ear to the ground in this era of environmental upheaval will not be surprised to learn that insects are another group sparking conservation concerns. We all know about the downward trend in pollinator populations, and the plight of monarch butterflies has long been front and centre. But it appears many other insect species may also be declining.

“The Insect Apocalypse is Here!” shouted a 2017 headline in The New York Times Magazine. Media outlets around the world were quick to follow suit, some substituting Armageddon for apocalypse.

Sensational headlines make great clickbait. But were they justified in this case? The media frenzy was a response to a study that documented a huge drop in insect biomass in Germany over 27 years. Between 1989 and 2016, the total weight of insects captured decreased by a whopping 75 per cent. This was a stunning decline over a tiny blip in time, but does a disturbing decline in one country signal a worldwide insect Armageddon?

The study’s findings certainly prompt some important questions. Is a similar insect decline happening on this side of the Atlantic? If so, what are the causes? Should we be concerned? And if concern is warranted, what can we do?

Is a similar decline happening here?

In answer to the first question, research on this side of the pond lacks the duration of the long-term German study, but we do have clues. I’m old enough to remember the mess – the spattered bodies of numberless moths, flies, beetles – on our Pontiac Parisienne after a summer night’s drive in the country. A stop at a gas station to squeegee the windshield was a regular necessity. Bugs still hit windshields, but unless my memory is faulty, not nearly in the numbers of yesteryear.

Also telling is that the number of swifts, swallows, flycatchers, whip-poor-wills and nighthawks is declining in Ontario and elsewhere. What these diverse bird species have in common is their appetite for flying insects. The pickings may simply not be what they once were.

More evidence of the insect decline in Ontario comes from the chimney swift, one of those aerial insect eaters. Or more accurately, the clues come from a pillar of chimney swift poop in a chimney at Queen’s University in Kingston. Starting in 1933, this chimney unintentionally collected six decades of data on insects in the Kingston area.

In the early 2000s, researchers jumped at the chance to plunge into this guano to build a chronological record of chimney swift diets over the decades. They found that, in the 1940s and before the insecticide DDT came into widespread use, the chimney swift droppings were filled with the indigestible parts of large beetles. In later years, the parts of smaller, less nutritious bugs dominated. The hypothesis suggests that DDT hammered the beetles so effectively that their populations remain depressed even today. And the application of DDT certainly wasn’t confined to Kingston. The notoriously toxic and long-lasting chemical was liberally applied throughout North America.

DDT was banned in 1972. But of course, other pesticides, including the controversial neonicotinoids, have taken their place. Though considered less toxic than the insecticides they replaced, neonicotinoids still disperse beyond treated agricultural fields into wetlands and other natural areas, and they also persist in the environment for a long time. Mounting evidence suggests they are killing not only their intended targets, but other insects as well.

What is causing the decline?

I sat down with Laura Timms, an ecologist with Credit Valley Conservation, to seek answers to my questions about insects, including her take on their perceived decline. Timms is passionate about insects. Before joining CVC she researched forest insects, which led her to learn about insect species at risk, invasive forest insects and parasitoids, such as wasps. Parasitic wasps have macabre life histories featuring a larval stage that unfolds within the living bodies of other insects.

While conceding there is “no smoking gun” to explain insect decline, Timms identified some of the usual suspects including habitat loss, invasive species and climate change. Habitat loss, I think, is an absolute given. Towns, cities and intensive agriculture eliminate the meadows, wetlands and woodlands where insects thrive.

A lemon cuckoo bumblebee. A cuckoo bumblebee will invade the nest of another species of bumblebee, kill or subdue its queen, and take over its population to raise its young. Photo by Robert Noble.

As for invasive species, they replace native plants – and the insects that feed on those native plants are left hungry. And in some notorious cases, invasive plants cause the direct death of insects. “Invasive species – dog-strangling vine is a good example – smell the same as native milkweeds, so monarchs lay eggs on it, but the larvae can’t develop,” said Timms.

Garlic mustard, another rampant invader in these hills, similarly fools the at-risk West Virginia white butterfly. The scent of garlic mustard beckons egg-laying West Virginia white butterflies by promising food for their larvae. But this is an illusion. Chemicals in the leaves of garlic mustard poison the hatchling caterpillars.

Sometimes the invasive culprit is another insect. Timms lamented the disappearance of the nine-spotted lady beetle, the familiar ladybug that countless children once urged to “fly away home.” Formerly common in Headwaters and beyond, these native insects appear to have been pushed aside by imported Asian lady beetles.

Timms also cites climate change as another reason for the decline, particularly of pollinators, as the blooming cycles of plants fall out of sync with the insects that visit their flowers.

Should we be concerned?

Alas, some of us will applaud the retreat of the biting, squirming, disease-carrying, plant-destroying, multilegged insect hordes. “Yes, they can annoy us,” said Timms. “Yes, they can be pests, and yes, they can transmit disease, but on balance, they do far more good than bad.”

Timms cited the findings of a 2006 American study that placed an annual value of $57 billion on four of the ecological services provided by insects: pollination, pest control, food for vertebrates and dung removal. This makes it difficult to argue with famed entomologist E.O. Wilson, who pointed out that insects are the “little things that run the world.”

But like me, Timms has reservations about monetizing the value of insects. She knows the “money argument” resonates with people, but she also knows that no monetary value can capture the joy and wonder of interacting with the beautiful and fascinating insects in our midst.

Still not ready to embrace the wonder? Perhaps learning more about some of the fascinating insects that live in these hills will help.

How about the fireflies that sparkle on sultry evenings? They glow without electricity and with very little energy lost to heat. This biochemical feat is made possible by an elixir of oxygen, calcium and a remarkable compound called luciferin. Not surprisingly, science would love to know how to produce abundant light the firefly way, but the quest has proven elusive so far. In the meantime, we can continue to enjoy their midsummer magic. That is, if they last. Fears that fireflies have joined the ranks of fading insects have led to a citizen science project called Firefly Watch [see below].

So many to amaze

Fireflies are amazing, but so are many other insects. A friend puzzled over an insect he described as a small helicopter flying lazily over his head. Intrigued, he searched the web for an ID, but it eluded him – until one day he noted the strange creature again and watched as it landed on a dying maple tree. He approached warily and was taken aback by the largest wasp he had ever encountered. He stared in wonder as the wasp uncoiled an improbably large needle-like organ and began probing the bark with it.

A female common eastern firefly. Her signal light is concentrated in the small “box” area of her abdomen, unlike male fireflies which have larger light organs. Photo by Radim Schreiber / fireflyexperience.org : Firefly.

My friend had found a giant ichneumon. The needle-like organ, which apparently can be seven centimetres or more long, was the wasp’s ovipositor – its egg depositor. Other wasps have sharpened their ovipositors into stingers designed to penetrate flesh. But ichneumons, which fall into the parasitic category of wasps, use their ovipositors not to sting, but to drill through bark and lay eggs on grubs inside trees.

Because parasitic wasps hold a special place in her heart, Timms knows giant ichneumons well. “They locate their hosts (horntail grubs) by tapping with their antennae and listening for a signature echo inside a tree,” she said. The flimsy-looking ovipositors manage to penetrate bark because they’re tipped with zinc and manganese, she added excitedly. Metal-tipped organic drill bits? Fascinating. Then when the ovipositor reaches a grub, its role morphs from drill bit to hypodermic needle, and it injects an egg. Bad news for the grub. The egg hatches, and like the monster in the Alien films, the ichneumon larva eats the host grub from the inside, before … ah … “popping out,” as Timms described it.

Female giant ichneumon wasps are able to lay eggs under bark with zinc- and manganese-tipped ovipositors. Photo by Robert McCaw.

Timms is also a big fan of ants. Though unwelcome when they move indoors, ants are among the most useful, important and fascinating of creatures. Like all insects they are food for other creatures, such as reptiles, birds and amphibians. Beyond their foundational role in food webs, however, ants have evolved truly remarkable communal behaviours. In fact, many of their practices are analogous to human behaviour, both benign and odious. An example of the benign is the “farming” of aphids for their sweet droplets of honeydew. Like human shepherds, ants protect their “flocks” from predators. And the odious? Ants engage in warfare, and some species enslave ants from other colonies. Of course, unlike us, ants can’t be held ethically culpable for these instinctual behaviours.

Timms offered the Allegheny mound ant as a local species worth knowing about. As their name suggests, these ants build mounds, often large mounds that sometimes rise a half metre or more above the surface of the ground. A network of tunnels extends as deep as two metres below the mounds and radiates several metres outward. Up to 10,000 ants can inhabit these earthen invertebrate towns.

Allegheny mound ants use herbicide to control the vegetation surrounding their homes, just as many of us did in years past. In a remarkable process these ants first score the bark of shrubs and tree saplings with their mandibles. Then they squirt formic acid into the damaged bark. After repeated applications their potent, homemade herbicide has the desired effect. The shrubs and trees die. The goal appears to be climate control, banishing shade and allowing sunlight to heat the interior of the mounds, providing the optimum conditions for developing eggs and larvae.

Allegheny mound ant. Photo by Robert Noble.

Before shaking your fist at this further evidence of the ruination insects cause, consider this. This vegetation control creates open areas that appeal to other sun-loving creatures, including snakes, butterflies and various species of birds. And in defence of all ants, it must be said that they, in their legions, reduce the need for chemical pesticides because they are important predators of insect pests that cause crop damage.

If ants rule the land, giant water bugs hold dominion over aquatic realms. By weight these are the largest insects in the world. Awesome predators, these bugs can subdue vertebrate prey, such as fish, frogs and tadpoles, with their fearsome bite. But “toe biter,” their colourful colloquial name, suggests they sometimes bite people as well. And though the chance of this happening is remote, it’s best avoided. Apparently the ouch factor is worse than a wasp sting! A gentler side of these megabugs is a male’s fatherly dedication to the eggs he has fertilized. He carries them on his back and protects them until they hatch.

The eggs of the giant water bug are carried on the male’s back. The bug’s bite is worse than the sting from a wasp. Photo by Robert McCaw.

If giant water bugs are the world’s heaviest insects, walking sticks are certainly among the longest. Never has a more appropriate name been conferred on an insect. They do look, for all the world, like an assemblage of sticks come to life. They embody the power of evolution to colour and shape animals in response to predators. And if sharp-eyed predators like birds find them difficult to see, it’s no surprise people seldom see them. This despite the fact that they are common in these hills.

What can we do?

How can we make the world a more accepting place for these amazing insects and all their six-legged brethren? We can continue to protect the Niagara Escarpment, the Oak Ridges Moraine and other local areas that provide excellent habitat for insects and other organisms. Saving different types of habitat – woodlands, wetlands and meadows – is also important. We can be responsive to research into the effects of neonicotinoids on non-target insect populations and look for ways to mitigate overall pesticide use in agriculture.

Anyone who owns a property, small or large, can make it more insect friendly. Timms looks to the findings of Douglas Tallamy, a University of Delaware professor who explored the connection between native plants, insects and birds in his highly acclaimed book Bringing Nature Home. Tallamy’s research revealed that insects thrive on the plants they’ve evolved with, that is, native plants. So more native plants – trees, shrubs, herbaceous perennials – translate into more insects and, by extension, more birds and other vertebrates. Timms stressed that native plants need not occupy an entire yard. “Any scale of conversion will benefit insects,” she said.

By the way, if you go native, Timms has an important message: “If you’re planting native plants to support insects, you have to allow that those insects will be eating the leaves. And most of the time that will be just fine.” Beyond the veggie patch, insect-chewed leaves should bring smiles, not frowns. Take oak leaves, for example. At the end of the summer they are often riddled with holes. This doesn’t portend doom for the tree. It will recover the following spring. What the holes tell us is that the oak tree is a functioning contributor to the local ecology.

Timms also gently suggests that we be less fastidious when wielding the garden rake in autumn. She endorses the Leave the Leaves campaign of the Xerces Society for Invertebrate Conservation [see sidebar]. One of the “most valuable things you can do to support pollinators and other invertebrates is to provide them with the winter cover they need in the form of fallen leaves and standing dead plant material,” advises the society’s website. Standing dead plant material refers to the stems of garden perennials that harbour overwintering bees and other insects.

If raking and tidying in the fall is simply part of your DNA, “at least consider raking leaves and other yard debris into piles,” said Timms. These brush piles will provide shelter for all manner of small, vulnerable creatures.

My Grade 6 science classroom was a “yuck-free zone,” an expectation that was always discussed on the first day of school – before I brought spiders, caterpillars and other fascinating invertebrates into the classroom. This pre-emptive banning of the predictable “yucks” and “eews,” as well as “gross,” one of the dullest and most depressingly dismissive words in the English vernacular, was inspired by my desire to nudge students away from their preconceived notions about insects – and to encourage young people to view insects with inquiring eyes and to offer bugs the respect they deserve.

Insects are not about to plummet into the abyss. There remains an excellent chance that cockroaches … and ants … and flies will inherit the earth after we’re gone. But if insects are declining – and the evidence certainly points in that direction – we need to find out why. A decline in the numbers of our extraordinary fellow travellers on planet Earth will lead not only to economic and environmental repercussions but also to a diminishment of wonder.

Get involved with insect science

Citizen Science Opportunities

iNaturalist | inaturalist.org

This free app for phone or desktop allows you to post pictures of insects – and all manner of other plants and animals – to get instant identification suggestions. It is also a valuable tool for mapping species’ distributions.

Bumble Bee Watch | bumblebeewatch.org

Like iNaturalist, Bumble Bee Watch has a phone app that enables you to post a picture and get identification help from other users, often experts. Laura Timms touts the value of this initiative because “a lot of bumblebees are threatened.”

eButterfly | e-butterfly.org

This is a site dedicated to butterfly observations. No phone app.

Firefly Watch Citizen Science Project | massaudubon.org

A North American firefly counting project run by Massachusetts Audubon and Tufts University in the United States.

Butterfly Blitz | cvc.ca

In July and August this year, Credit Valley Conservation will promote the collection of butterfly data in the Credit River watershed. Send your pictures and data to iNaturalist or eButterfly.

Credit River Watershed Butterfly Count | cvc.ca

This one-day event set for Saturday, June 29, with a rain date of Sunday, June 30, will take place within a 24-kilometre circle centred on Belfountain in Caledon. Within this circle, teams will count butterflies in areas open to the public.

Organizations

Toronto Entomologists’ Association | ontarioinsects.org

The TEA offers regular meetings, field trips and an information-packed website. Individual membership is $30.

Entomological Society of Ontario | entsocont.ca

The ESO produces a biannual newsletter and a journal. They also host Bug Day events in Ontario cities. Membership is free for students and seniors; $30 for others.

Xerces Society for Invertebrate Conservation | xerces.org

An international nonprofit organization active in the conservation of insects and other invertebrates. Its website is an excellent resource for anyone interested in insects and their well-being.

Related Stories

Bumblebees

Jul 5, 2010 | | BlogsAt this time of year when we celebrate Canada Day, Don Scallen celebrates the hardy bumblebee, the “true Canadian” of the insect world.

Meet Mulmur’s New Beekeepers

Jun 21, 2017 | | FarmingHow the Heritage Bee Company is boosting the honeybee population in Headwaters and inspiring newbie beekeepers.

Flight of the Bumblebee (and other pollinators)

Jun 15, 2010 | | EnvironmentIn “Flight of the Bumblebee” Don Scallen says we owe a debt of gratitude to pollinating insects for keeping food on the tables of the human race!

Invasive Species in Our Backyard

Jun 19, 2018 | | EnvironmentThey’re big. They’re strong. And they’re probably here to stay. But keeping them in check will give native plant species a chance.

Monarch Butterfly – RIP 2026

Aug 9, 2013 | | BlogsMost of us are old enough to remember when monarchs were a frequent sight in meadows and gardens.

Swifts and Swallows

Mar 23, 2014 | | EnvironmentThese birds fly with grace and verve, flitting over fields and wetlands and high above towns and villages.