From Rails to Trails

Tearing up tracks for a place to go slow.

It might surprise you to know that the rail lines of Headwaters now carry more people than ever. But these travellers don’t ride in passenger coaches. Instead, they walk, hike, run, cycle, ski, snowshoe, ride on horseback and, on one line, drive snowmobiles and all-terrain vehicles. In 2017, according to the Town of Caledon, 85,000 people used the former rail line that is now the Caledon Trailway.

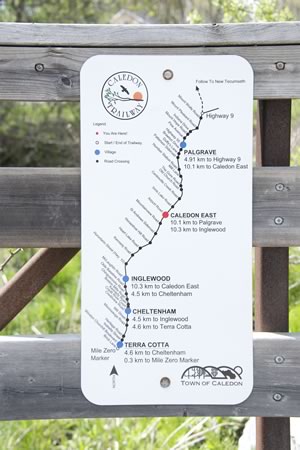

In Headwaters, the Caledon Trailway kicked off the conversion of rail lines to rail trails. In 1989, the town purchased a 35-kilometre section of what was once the Hamilton and North-Western Railway for $30,000. The corridor runs diagonally across the entire municipality – from just east of Palgrave to just west of Terra Cotta. The trailway may not link us from sea to sea, as celebrated in Gordon Lightfoot’s “Canadian Railroad Trilogy,” but it does connect Caledon from northeast to southwest.

Since its purchase, bridges have been repaired and added, benches constructed and interpretive signs installed. Other rail trails followed suit. Credit Valley Conservation and the Grand River Conservation Authority jointly bought the Elora-Cataract line of the onetime Credit Valley Railway to create the Elora Cataract Trailway. The town of Grand Valley picked up a section of the Fraxa-Teeswater branch of what started out as the Toronto, Grey and Bruce Railway, and transformed it into the Upper Grand Trailway, from Waldemar to near the Luther Marsh. And Dufferin and Grey counties acquired the Orangeville-Shelburne-Owen Sound stretch of the TG&B’s main line and converted it into the CP Rail Trail. In total, more than 100 kilometres of rail trails criss-cross Headwaters.

Having completed end-to-end journeys on foot or astride my bicycle on all but the CP Rail Trail, I’ve come to realize that rail trails differ from other recreational paths. Their width makes them chat-friendly because you can walk two or three abreast. They are also flat, making them attractive to hill-averse cyclists and wheelchair users. Furthermore, rather than avoid populated areas, rail trails often pass right through the centre of towns and villages. Sometimes subdivisions include public paths that link them to rail trails. When combined, these features make rail trails linear meeting places.

Though I might see one or two people when I hike the Bruce or Humber Valley Heritage trails, I’m unlikely to travel along a rail trail without seeing a handful of fellow hikers or cyclists, especially when I’m close to a town or village. Users beget users. Rail trails are a place to meet up with friends to walk your dog, debate world issues or bemoan the fate of the hapless Leafs – all while getting exercise.

But that’s not all. Rail trails serve a purpose not dissimilar to England’s hedges. In addition to being living fences, English hedges provide habitat for birds and other critters, including those cute hedgehogs. They are windbreaks and transportation corridors. Some English hedges date back to Roman times and are so much a part of the countryside they are marked on maps.

Our rail trails are comparatively new. After all, our railways didn’t arrive until the 1870s. Nonetheless, these corridors record our pioneering past and are also often included on maps. They are our historical rights-of-way, connecting towns and villages to one another and to parks, conservation areas and other trails. They provide public access at a time when the rural landscape is under relentless pressure to urbanize, and when physical (vs. cyber) connectivity is ever more tenuous. We need to cherish and protect them, a notion clearly shared by the caretakers of the Upper Grand Trailway as it passes through Grand Valley-East Luther. They maintain that trail with the care of a parent.

A couple of summers ago, I hiked the 10.5-kilometre Upper Grand Trailway along the old TG&B branch line from Waldemar through Grand Valley to the East West Luther Townline near the Luther Marsh. The trail was meticulously mowed and trimmed. There were benches to rest on and the occasional interpretive sign. At many of the road crossings, I noticed cut-off pop bottles. Inside were plastic bags, a friendly reminder for dog owners. This is clearly a well-loved and well-used route.

More recently, as I hiked the Caledon Trailway from end to end over two days, it felt like walking among old friends. Spring was budding all around me. Migratory red-winged blackbirds and red-breasted robins added their distinctive songs to those of overwintering blue jays, cardinals and chickadees. Ruffed grouse pumped away and turkey vultures soared overhead. Tender green buds decorated lilac trees, and I was delighted to see soft, fuzzy pussy willows, a sure sign of spring.

Constructed on the former tracks of North-Western Railway, Caledon Trailway covers 35 scenic kilometres from Terra Cotta to Highway 9. Photo by Pete Paterson.

The linear nature of rail trails means they take you from watershed to watershed, from moraine to escarpment, from village to village. On the Elora Cataract Trailway, travellers leave the Credit River watershed just west of Hillsburgh and cross into the Grand River watershed. Travelling westward on the Caledon Trailway takes you from the hummocky terrain of the Oak Ridges Moraine in the Humber River watershed to the Credit River watershed where the Niagara Escarpment dominates. Sandy soil gives way to rocks and gravel and terra cotta clay, and you cross old cut-stone trestle bridges that have been in place since the navvies built the railways some 150 years ago.

In his “Canadian Railroad Trilogy,” Lightfoot sings about laying down tracks and tearing up trails to “let the lifeblood flow” because “we’re moving too slow.”

But the times, they have changed. Those historic pathways have traced human aspirations through more than a century, and now as the world speeds by, we’re tearing up tracks and laying down trails to “let the lifeblood flow” by creating a place to go mercifully slow.

Related Stories

Caledon Hikes

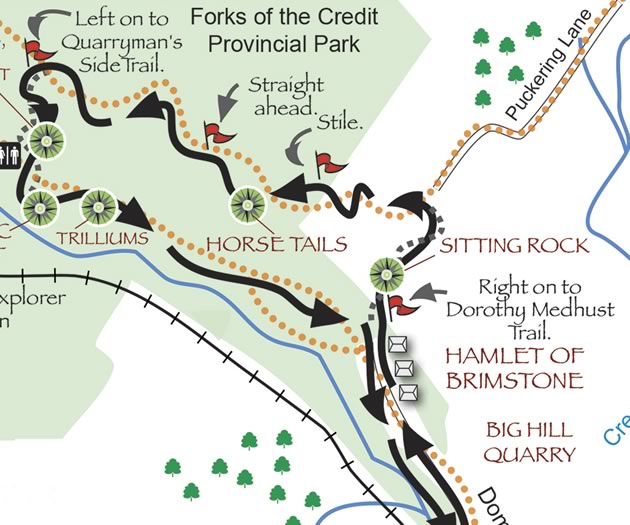

Jun 16, 2015 | | LeisureNicola Ross shows readers how to navigate local Caledon trails, including the Bruce Trail and the Trans Canada Trail, without having to backtrack or arrange to leave a car at a hike’s endpoint.

An Audacious Idea – The Bruce Trail Turns 50

Mar 23, 2014 | | Good Sport“What,” Lowes asked, “would you think of a hiking trail winding up the Niagara Escarpment from one end to the other?”

Spring Hikes on The Bruce Trail

Mar 26, 2018 | | EnvironmentAlong the Bruce Trail, spring is the time to slow to a saunter and see, hear and scent nature’s renewal.

Nordic Pole Walking

Sep 18, 2018 | | Good SportWalking with poles: the fashionable walking stick morphs into essential hiking gear.

Take a Walking Tour of Orangeville, Inglewood or Hillsburgh

Jun 21, 2017 | | HeritageSoak up some fascinating local history and stroll the sidewalks of our towns and villages.

Take a Walk on the Wild Side: Forest Bathing

Mar 26, 2018 | | Good SportSlowing down, tuning in. With forest bathing, the slow movement takes to the woods.