An Ode to the Tiny House

The idea of living small is undeniably alluring. Some folks in these hills are doing more than flirt with the romantic fantasy.

When Mono sculptor and artist John Farrugia leaves work for the day, he steps out of the foundry where he creates massive bronze statues and commutes just a few paces. You would be forgiven for thinking the small nearby structure he enters is a pit stop en route to his home. But no, it is his home. A mere 10 by 10 feet square, the tiny house includes a main floor sitting area, a storage cellar and a sleeping loft. John created it in 2014, a year after he built his foundry in an old barn foundation.

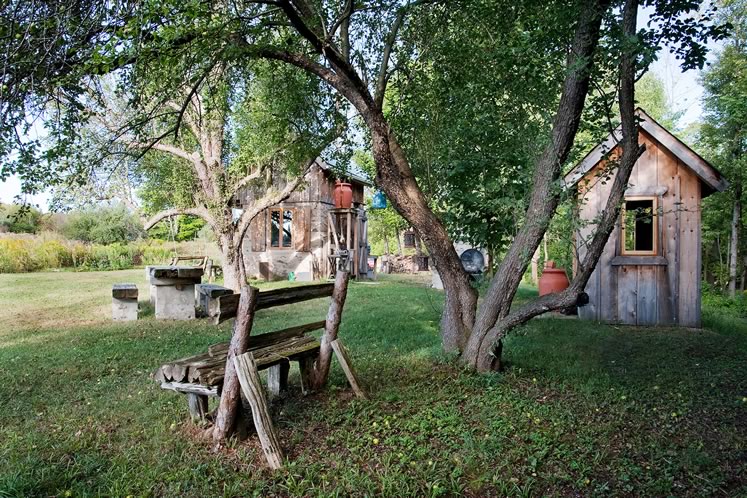

Sculptor John Farrugia built a tiny home on his family property in Mono. Photo by Rosemary Hasner / Black Dog Creative Arts.

His Lilliputian home exists in part because John enjoyed learning about stone masonry as he built the foundry. “I wanted to mimic the stonework of the foundry,” he says. “It’s like a sculpture to me.”

The stone walls of the “wee house,” as he calls it, are topped with timber framing and a steel roof. Because he kept the structure tiny, at 100 square feet and with no plumbing, no building permit was required. An outhouse is in the works and the back of the house features an outdoor sink and shower hooked up to a rain barrel. A pizza oven, rustic dining table, benches, and seats swinging from nearby trees expand the living quarters.

An outdoor kitchen, pizza oven, outhouse and sturdy wooden furniture expand John Farrugia’s living space. Photo by Rosemary Hasner / Black Dog Creative Arts.

The whole complex sits on a communal family property where his parents and two of his siblings have homes. When family and friends visit his setup – as they did during his August wedding to Carol Kwak – they embrace the romance of it. “The kids love it because everything is miniature,” says John. “The adults say, ‘I’ve always had this dream of living in a treehouse.’”

Wee homes like John’s are having a moment. As houses in Canada have continued to supersize – in 1975 the average home size was 1,050 square feet, but that figure had doubled by 2010 – many of us feel the allure of living in a pint-sized package. We tune into tiny home living shows and websites, in awe of the discipline it would take. After Marie-Kondo-ing our stuff, we imagine, we would get down to basics and live with just the bare necessities. Today, the impulse is more about esthetics and eco-living than financial necessity, but the trend also builds on historical precedents such as diminutive postwar 1950s bungalows and the small mobile home communities that started sprouting in the 1960s.

Though intrepid souls like John do make it happen, it can be more challenging to build small than it is to go big these days. If you’re on the Niagara Escarpment or other protected lands, you may be completely out of luck. Many municipalities require a minimum dwelling size and some stipulate only one residence per property. If they do allow a secondary building, other factors can influence whether you gain approval – how much land you have (some areas, for instance, require a minimum of 25 acres before entertaining a second dwelling application), how your land is zoned, a maximum distance from the primary residence and your road, your plumbing plans and more. To learn what is or isn’t allowed requires submitting plans and, usually, a few thousand dollars in application fees.

A hand-forged sign welcomes visitors to John Farrugia’s tiny home. Photo by Rosemary Hasner / Black Dog Creative Arts.

In Mono, if you’re building a home any bigger than John’s, the smallest you can go is slightly less than 800 square feet – if your application meets all other requirements. In Mulmur you are in theory allowed to build a guest cabin as small as about 215 square feet as a secondary dwelling. In Grand Valley the minimum for a “garden suite,” which is not considered a permanent residence, is about 377 square feet.

Though tiny homes are often designed to be temporary and off-grid, or with just a water hookup, many of these dwellings will be plumbed and use municipal services. As a result, potential owners will face all the associated development fees, costs and challenges of any on-grid home. So for most, until building codes get a makeover, living in a permanent pad of less than 400 square feet – the common definition of a tiny home – remains an elusive dream.

Sue Graham of Riverdale Farm and Forest sits on the steps of her caravan-on-wheels. Photo by James MacDonald.

The caravan serves as sleeping quarters for visitors to the farm and a rental bunkie for neighbours in the village of Inglewood. Photo by James MacDonald.

The cozy bedroom space inside the Riverdale caravan-on-wheels. Photo by James MacDonald.

Still, it’s a dream kept alive around the edges with guest suites, bunkies and other temporary digs, which can be a whole lot of fun. As you drive through the picturesque village of Inglewood, for instance, it’s hard to miss the whimsical bunkie perched on the front field of Riverdale Farm and Forest. At first glance it looks like a covered wagon from a bygone era. It’s a delightful caravan reimagined as a functional bedroom on wheels.

“I always wanted my own caravan so that I could sleep out by the river, forest or field right on our own property,” says Susan Graham, who owns the farm with her husband, Owen Goltz. She gets a dreamy look in her eyes when telling the tale. “Owen built it for me and I furnished and decorated it minimally and sustainably with salvaged items. I just love the peace and charm of the result.”

Sue and Owen originally used the caravan as extra lodging for guests who have come to learn about the couple’s approach to regenerative farming at Riverdale. When guests elect to hunker down in the bunkie, a separate toilet and shower outbuilding can be parked alongside to allow for a more complete lodging experience, and a propane-fired grill is available for cooking al fresco.

The duo soon realized there was another use for their creation. Neighbours often need an extra room or a place for a staycation, so the duo will wheel the 8-by-12-foot bunkie to local backyards as a temporary private bedroom. With its pale blue walls, massive windows on two sides, vintage curtains and bedding, the bunkie is an attractive option, and it’s easy to understand why guests at a neighbour’s recently drew straws to see who would stay in the coveted space.

“It has been quite popular, especially to offer guests and hosts alike a bit more privacy than having someone sleep in the living room,” says Sue. “I can see adding a couple more bunkies, each with its own design and personality, to round out the fleet. Clearly I’m not the only one who simply doesn’t enjoy sleeping in a tent any longer!” The couple has also started a tiny house club, open to new members.

A Güte cabin at the Leisure Time Park near Palgrave. Photo by James MacDonald.

The tent alternative has also taken root at Leisure Time Park near Palgrave. For the past two years, the Jay family has offered Güte cabin rentals for between $79 and $99 a night. The 100-square-foot Scandi-chic cabins are handcrafted in nearby Maxwell to be minimalist but stylish, with room for four to sleep cozy and dry, and a pullout table that allows for playing board games and eating indoors. Cooking takes place outside, and washroom and shower facilities are available nearby in the park, just as they are for camping and RV patrons.

Like Susan Graham, Alyssa Marchment found herself captivated by the idea of living in a tiny house on wheels – and she’s building her own on a family member’s property in Milton. The home boasts 200 square feet on the main level, with an additional 100 square feet of loft space. The Jill-of-all-trades currently works part-time at GoodLot Farmstead Brewing Co. in Caledon, at a bakery in Burlington, and as a Reiki practitioner and yoga teacher. She hopes to rent space to park what will essentially be her mobile home on a rural property in Headwaters.

Alyssa Marchment is building a 200-square-foot tiny house on wheels and hopes to find a spot for it in Headwaters. Photo by James MacDonald.

The exterior of Alyssa Marchment’s tiny house on wheels. Photo by James MacDonald.

“The benefits of tiny home living include living a simple, if not easy, life,” says Alyssa. “My THOW (tiny house on wheels) will be fully off the grid, but with the ability to hook up to an external water source. Otherwise, it will be solar powered, heated with a woodstove with a propane furnace backup, and use a compost toilet plus rainwater catchment off the roof. This excites me but may scare off some others. I’m conscious of my environmental impact and this is just one of the ways I can help to reduce it.”

Alyssa already has some experience with living tiny, first at a very small studio apartment out west and then in an Airstream trailer at GoodLot for a few months while she worked as an intern. Although Alyssa has gratefully received tremendous support from family and friends, one of whom is a contractor with more than 35 years’ experience, she designed the entire home herself, incorporating a few favourite elements gleaned from tiny homes she has toured over the years. She describes her house as “a home that’s all me.”

The lessons Alyssa has learned extend beyond building. “It can be mentally straining, being the sole driving force, involved in every single decision, including about things you don’t even quite understand yet, since every single part of this project is brand new,” she says.

For those interested in a smaller and more sustainable home while leaving the building to professionals, Kathy Ratchford of Contained Living in Caledon transforms shipping containers into functional, even glamorous homes. Last year she debuted one of them at the Toronto Fall Home Show.

Kathy Ratchford of Caledon’s Contained Living transforms shipping containers into functional, even glamorous homes. Photo by James MacDonald.

The sleek interior of one of Kathy Ratchford’s shipping containers houses. Photo by James MacDonald.

Kathy points out that, where regulations allow, a shipping container home can enable grown children to live separately on their parents’ property. Likewise, aging parents can have a home close to family without sacrificing independence or forking out for costly assisted-living accommodations. Building costs range from $250 to $300 per square foot. Kathy’s show model is made of two 8-by-20-square-foot shipping containers for a total of 320 square feet. The starting cost is $80,000.

And no, you wouldn’t be living in a rusty CN relic. The model home’s exterior is a deep charcoal grey accented with barn board. The interior features a gleaming white kitchen, a bright living space with a Murphy bed and full-size designer bathroom. Steel shipping containers resist rot and other weather ravages to which “stick houses,” as Kathy calls them, are subject. Other advantages are shorter construction timelines and a clean worksite.

No shipping container homes have yet been sold in Headwaters. In Caledon Kathy is bumping up against requirements that homes be a minimum of 1,200 square feet, a far cry from tiny. So her structures would have to meet regulations for secondary dwellings.

The local landscape

Orangeville councillor Grant Peters, an environmental advocate and green building expert, notes that at the root of local permitting issues is the Ontario Building Code, which specifies minimum room sizes for dwellings. And once these are summed up, the totals usually surpass the threshold for a tiny home. A building official could conceivably rule favourably if it were shown that space was adequate after accounting for built-in furniture and storage, he says.

It’s a bit of a slog, but one that the future may require, especially in populated towns like Orangeville, he says. North America suffers from an unfortunate history of development, with a lack of properly planned density and a drive for size over quality. The councillor does, however, see a trend toward more innovative building solutions, especially in the housing market, including co-op housing, shipping containers and tiny homes.

“Orangeville, like Toronto, actually has a unique opportunity to take advantage of its long properties and laneways to accommodate more housing,” he says. “This will not please some people, but in the larger picture we have to understand that Orangeville is an urban centre, and we need to consider these types of solutions to prevent the sprawl into our neighbouring municipalities and farmland.”

If the regulatory obstacles can be minimized, he believes tiny homes will eventually make up a small portion of the traditional housing market. “As with most issues, a balance is often the best solution, so a combination of larger (condo/co-op/rental buildings), medium (traditional single family homes and townhouses), and smaller (tiny) homes can suit the needs of a community our size.”

This combination would also address people’s space requirements as they evolve over their lifetimes. John Farrugia’s tiny home suited him well when he was single, but now that he’s married he needs more space and proper plumbing. He and Carol, who has been bunking in the sleeping loft when she’s not working and staying in Toronto, are currently building a new 2,000-square-foot home on the same property. Here’s betting they’ll more than occasionally decamp to the tiny house as a reminder of the simple life.

Tiny homes in Headwaters and Beyond

1950s

Orangeville’s explosive growth after World War II extends to building small bungalows on Third Street, west Zina Street and south Bythia Street, the last houses built downtown

1960s

Stanley Park in Erin advertises vacation cottages, starting its transition to the current mobile home park, now an established neighbourhood

1997

Portland, Oregon, becomes synonymous with the tiny home trend as the city removes limitations on building “accessory dwelling units”

1999

Tumbleweed Tiny House Company, the first to sell mobile tiny homes in the U.S., is founded

2008

U.S. mortgage crisis boosts interest in living smaller and more frugally

2014

Tiny House Hunters debuts on HGTV

2015

Tiny House Community K-W debuts on Facebook and actively lobbies for regulatory changes to allow a tiny home community in Kitchener-Waterloo

2018

Caledon’s Contained Living reveals new shipping container home at the Toronto Fall Home Show

For more ideas, visit

Related Stories

Going off the Grid

Jun 21, 2017 | | EnvironmentFor Mary and Brad Kruger, living lightly doesn’t mean sacrificing comfort for conscience.

The Art of the Blacksmith

Sep 18, 2018 | | ArtsDedicated artisans keep the art and craft of metalworking alive, from historical artifacts and statues to decorative architectural railings.

Home is Where the Art is

Jun 20, 2019 | | At Home in the HillsWhen entrepreneurs and artists Jocelyn Burke and James Webster renovated Jocelyn’s childhood home in Horning’s Mills, they laid the perfect groundwork for a well-curated life.

Living Large Atop Henning Salon

Jun 21, 2017 | | At Home in the HillsTo simplify life at work and home, this Orangeville couple created the ideal urban loft.