The Night the Dams Broke

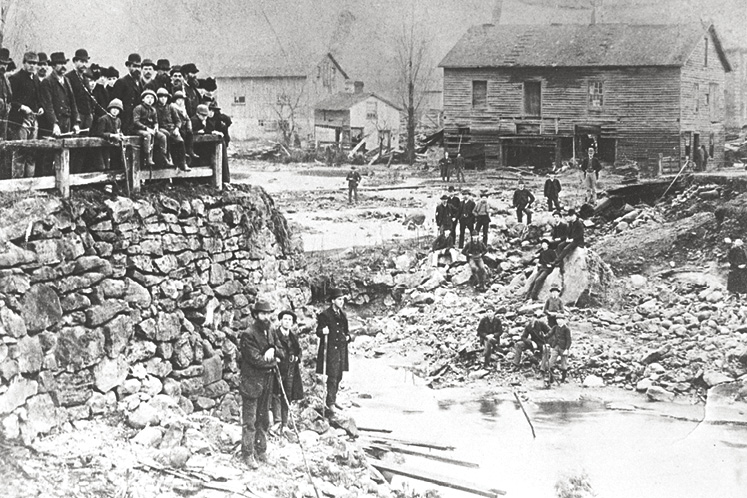

Two hours before dawn, on November 13, 1889, the great Alton flood disaster took place when a series of dams failed to hold strong.

No one in the village of Alton noticed the ragged old man shuffling along Amelia Street at dusk. He was keeping to the shadows. Anyone seeing him would have called him a tramp. This was 1889 and people didn’t use soft labels. Not that the man was a threat of any kind. He’d come up from the railroad tracks and was just looking for a place to sleep. Found it too. A big iron dye kettle beside the Beaver Knitting Mills on the edge of Shaw’s Creek, half full of yarn ends.

In their little frame house a little farther down the creek, John and Ellen Harris did not see the tramp. They had gone to bed early. John, after all, was eighty years old and Ellen, seventy. Nor did the Whethams next door. They were still up for their newborn baby was croupy and fussing. Their two-year-old wasn’t feeling well either. When the Whethams finally got to sleep a few hours later, both children together with them in a little bedroom, they were completely exhausted.

Not only did the tramp go unnoticed that night, so did the creaking sounds coming from the McClellan Bros.’ mill dam. But then, the dam was out at the edge of town and had been making those sounds for a while now. Twice in the past year, the huge pond it held in check had to be partially drained to effect repairs. Maybe that’s why the noise didn’t cause a stir. By midnight, as the creaking got louder and popping sounds began, nearly everyone in Alton was too cosily asleep to pay attention.

Two hours before dawn, on November 13, 1889, the centre post of the McClellan dam gave one final crack, tore free of the structure and shot to the surface. For agonizing seconds the dam leaned downstream in a lazy stretch. Then it blew apart. A wall of water 16 feet (5 m) high roared down the valley into town. In seconds it reached the next dam at Alton Knitting Mills, this one holding another large pond. Again there was a pause in slow motion until this dam, too, went down. The wall of water was now 20 feet (7 m) high, a roiling mass that quickly took out another dam (an unused one owned by the McClellans), before launching itself at Beaver Knitting Mills.

Here, the dam held. It was new and strongly built. Still, there was too much force to be contained and the torrent simply went around the dam, demolishing the Beaver mill and gouging out a trench sixty feet (18 m) long. Next up were Dick’s Dominion Foundry and Meek’s Alton Flour Mills. The flour mill survived intact, but its dam literally disappeared. At the foundry, part of the dam held, but as with Beaver Knitting Mills upstream, the buildings took the punishment. A witness later said that the foundry’s moulding shop broke up “like snow melting in June.” The shop was a single storey built entirely of stone!

It was at this point, with only one dam left before the creek joined the Credit River outside of town, that the great Alton flood disaster had simultaneous moments of tragedy and joy, the kind of paradox so typical of events like this. John and Ellen Harris, just a short distance downstream from the Alton Flour Mills, never had a chance. Their little frame house was torn apart. John’s body was found the next morning, while Ellen’s became the subject of a town-wide search. Ironically, her body was found at the same time her husband’s funeral cortège was filing toward the cemetery.

Next door to the Harrises, the Whetham’s fate became the stuff of legend. Despite the booming and crashing, they didn’t wake up until their bed actually began to float. Again, it was a matter of seconds. The father, Thomas, grabbed their two-year-old with one arm and hung on to the top of the bedroom door with the other. Mrs. Whetham stayed on top of the bed until she was pressed to the ceiling. Meanwhile, a neighbour, Peter Lemon, shouted from the hill behind them.

“Keep up! The water’s going down!”

And it did. In a few minutes, everyone was back on the floor, albeit in a layer of mud. Only then did Mrs. Whetham scream. The baby! Where was the baby? Safe and sound asleep as it turned out. To make the miracle complete, the cradle had floated up and then back down like everything else.

By the time the Whethams emerged from their house, shocked and horrified like everyone else in Alton, the wall of water had lost its power as it moved downstream. McKinnon’s dam, the last on the route, was barely touched, although the water had still enough force to damage the railway bridge on the former Credit Valley line. Alton, meanwhile, on either side of Shaw’s Creek, was a mess. Three of the village’s bridges were out. Sidewalks were gone; roads washed out. Livestock was scattered. Pieces of houses and furniture were strewn about, and damage to the mills, although initially reported at only $25,000 – in 1889 dollars – was not covered by insurance.

At daybreak, Shaw’s Creek was gently seeking out a new bed for itself in the altered landscape. By evening, it had returned to its calm, meandering state, and the people of Alton were busily cleaning up.

And what of the town’s newest, if temporary, resident? When the flash flood tore around the dam at Beaver Knitting Mills, it had taken the homeless man for a wild ride in his dye kettle bed. He was found well downstream next morning, unharmed but more than a little befuddled. His only comment for the record was that, all in all, he should have stayed in Brampton.

More Info

About the dams

In 1889, Alton’s population was about 750. This size of population, along with the fact that water was the preferred power source, would account for the high number of dams in the community. Of the seven dams affected, three were completely destroyed. Most were wood and earth structures, and few were designed to accommodate a big surge.

A meteor hits

According to local historian, Ralph Beaumont, in the 1920s a large meteor landed in the mill pond at Dods Knitting Mills, for years a prominent industry in Alton. The pond not only provided water for powering the mill but did double duty in summer as a swimming hole. The meteor was said to have made the pond actually boil and for days rendered it too hot to swim in.

Related Stories

William Algie

Mar 16, 2024 | | HeritageThis manufacturer, master storyteller and community builder left an indelible mark on the village of Alton.

Bad Night on Caledon Mountain

Jun 20, 2008 | | Back IssuesOn a cold, dark November night in 1941, just when the war news from Europe was bleaker than ever, a fatal plane crash in Caledon Township showed that even training for war was perilous.

The Wreck at Horseshoe Curve

Oct 25, 2023 | | Historic HillsA famous railroad engineering design in Caledon Township became the site of a disaster on a September morning in 1907.

A “Snow Blockade” Wreaks Havoc

Nov 27, 2023 | | Back StoryAlmost 18 feet of snow fell in February 1904, bringing train travel to a halt and stranding hundreds of passengers north of Shelburne in the cold.