William Algie

This manufacturer, master storyteller and community builder left an indelible mark on the village of Alton.

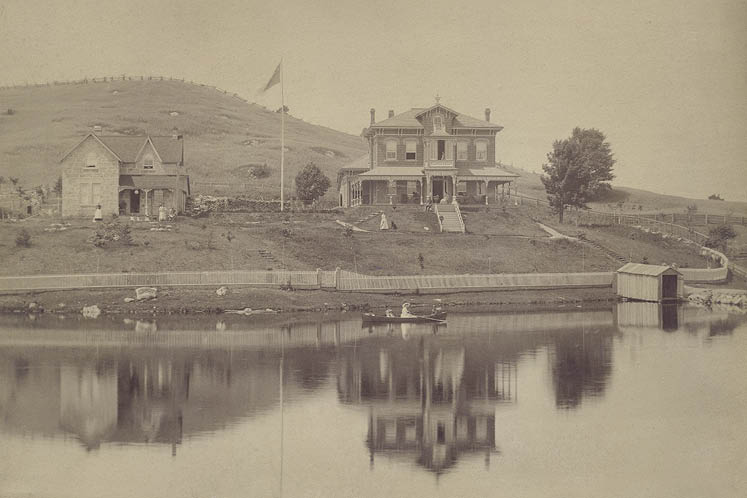

If the walls of the red brick Italianate house perched so majestically over Alton’s lower millpond could talk, what stories they might tell of its original owner, philanthropist William Wallace Algie.

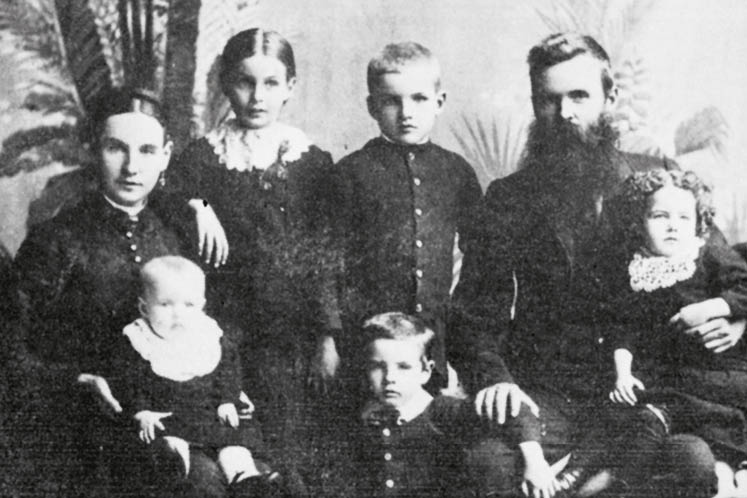

By trade, William was simply a mill owner. Yet a rummage through historical records reveals his generous contributions to village life, suggesting that he – and his wife, Phebe – should be remembered as prominent shapers of the early community. This renowned raconteur, international guest speaker and world traveller can also be linked to American author Mark Twain, the ill-fated Titanic, and one of the vilest murders in southern Ontario.

Born in Ayr, Ontario, in 1850, William was the eldest son of Matthew and Janet Algie’s seven children. His mere grade school education belied his tenacious personality, ever-curious mind and penchant for lifelong learning. At 16, he apprenticed as a spinner in a Dundas woollen mill until newer, faster machinery replaced the old hand-spinning techniques. Undaunted, William mastered the new machines and advanced to the position of superintendent.

After he married Phebe Ward, William and his father-in-law, Benjamin Ward, moved and leased Graham’s woollen mill in Riverdale (now Inglewood) for three years. Though a disagreement dissolved their partnership, both men soon ended up in Alton, running separate woollen mills on Shaw’s Creek, a branch of the Credit River.

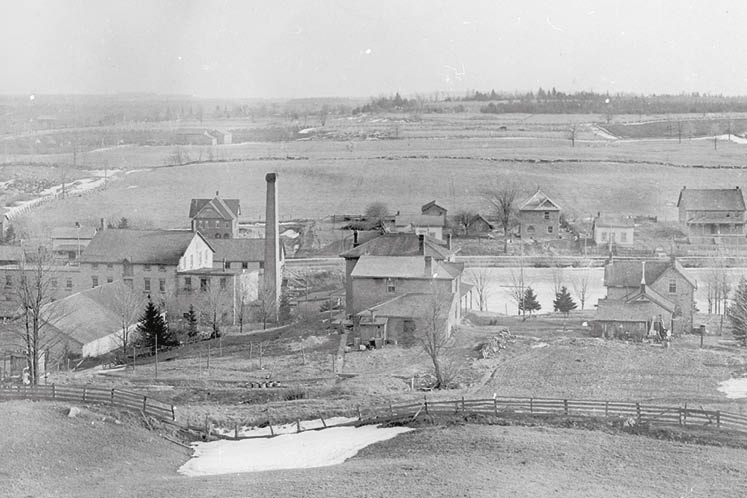

On two of the village’s nine mill privileges – sites where owners could build mills provided they didn’t violate the rights of other landowners – William built and operated Beaver Knitting Mills in the stone building that is today’s Alton Mill Arts Centre. The mill’s quality fleece-lined long underwear became renowned across Canada. He employed more than 60 workers, and business prospered despite Alton’s major 1889 flood and a devastating fire in 1908 that closed the business until the damaged machinery could be replaced.

William served as president of the Canadian Secular Union in Toronto. He proudly proclaimed himself a freethinker, like his father before him. In Paisley, Scotland, their forebear James Algie was hanged on February 3, 1685, for refusing to accept the king’s supremacy in all civil and religious matters. A towering monument in the graveyard of what is now Martyrs’ Church in Paisley honours James’ memory.

William’s strong bias toward finding life’s answers in science rather than religion motivated him to build the Science Hall next to the mill. The 300-seat hall, now converted to private homes, flourished as the cultural hub of the village, featuring international guest speakers, rousing recitations and orchestra music. The drama club and brass bands rehearsed and performed there. The hall also housed the town’s drama club, organized by William’s brother Robert, who ran the highly successful Algie Bros. general store on Queen Street. Admission to the hall was free and open to all religious denominations.

If anything, William loved a good party. For more than two decades, his family hosted the area’s biggest blowout social event of the year: the Drummers’ Snack.

At the time, “drummers” were commercial salespeople who travelled the countryside to drum up business (hence the term drummers) – and William wanted to attract them to Alton. The Drummers’ Snack Club was designed not only to organize these notoriously independent operators into a professional association but also to boost the local economy.

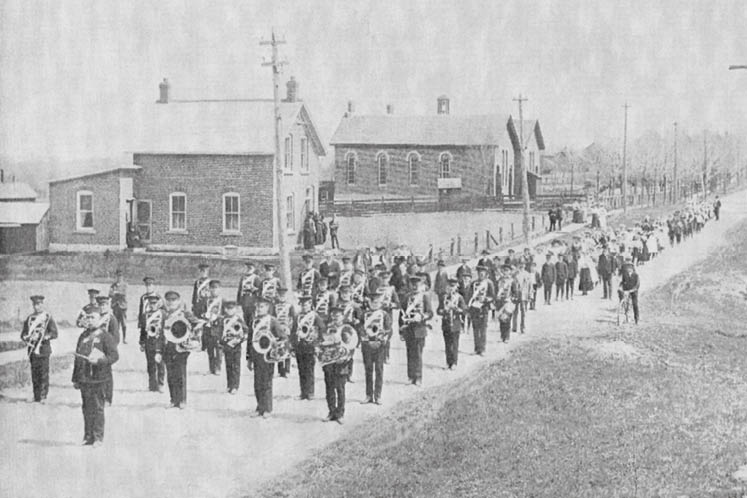

With the help of Phebe, his brothers and villagers, William’s scheme paid off. On August 1, 1892, a headline in Toronto’s Globe newspaper read: “Drummers’ Snack: Picnicking Travellers fill Alton with Jollity.” The Drummers’ Snack became an annual July fete as throngs of drummers were greeted at the Alton train station with great fanfare.

After the mayor’s welcome, the Alton Citizens’ Band, which William financed, escorted the visitors to the village hall for a welcome dinner. This was followed by a flamboyant masquerade parade to Beaver Hill, the Algie home. “The old and fantastic costumes outshone any carnival Venice ever saw,” reported The Globe.

Sprawling across the grounds of Beaver Hill, more than 400 villagers, farm families and day-trippers from 30 miles around joined the drummers for this unique fusion of garden party and trade fair. Carnival tents housed vendors’ tables laden with sales items that ranged from shoes and linens to candy and kitchenware.

The food tables were helmed by Phebe in her makeshift outdoor galley nicknamed the “Cyclone Cellar.” With help from the village women, hot and cold meals sated the hunger of the masses for the entire weekend.

The event roster was an exhaustive jumble of madcap games, races and competitions of every kind, for every age. Millpond swim races, burlesque baseball, a baby show and a broomball match for women were just a few. In the days before movie theatres and television, the highly popular evening programs featured recitations, dramatic plays and orchestral music.

Every room in Alton’s five hotels was fully booked, with the overflow of drummers billeted with local families. The event was a spectacle! And a success! But as annual attendance grew, it fell victim to its own soaring popularity. A staggering 3,000 people attended in 1904. Numbers like this eventually exceeded the Algies’ ability to handle the crowds, and the Drummers’ Snack moved to Erin in 1909. Later, communities such as Oakville, Georgetown and Elora competed for the privilege of hosting the event.

In 1882, William financed and built Alton’s first library, or Mechanics’ Institute, as libraries were called at the time – with Robert as the first secretary and librarian. The Alton Mechanics’ Institute housed nearly 3,000 volumes of technical books providing educational material for tradespeople and skilled labourers, many of them workers at the village’s many mills. By the turn of the 20th century, most Mechanics’ Institutes had been transformed into public libraries. And so William’s small brick building on Queen Street served as the community library for over 100 years until 1990, when it was replaced by a newer, bigger library on Station Street.

Various archival notes describe William as a “prince of a storyteller,” a “stirring orator” and fittingly, given his role as a woollen manufacturer, someone who “loved to spin a good yarn.” In 1896, for example, he was the guest speaker at the unveiling of a memorial statue in Listowel, Ontario. Sadly, the occasion commemorated the death of 13-year-old Jessie Keith, victim of a brutal Jack-the-Ripper-style murder.

William’s guest appearance was documented by John Goddard in his true crime book The Man with the Black Valise. The book, which follows detective John Wilson Murray as he tracks Jessie’s killer, inspired the creation of the fictional detective William Murdoch of the popular TV series Murdoch Mysteries.

In 1901, William co-hosted the Duke and Duchess of York, later King George V and Queen Mary, when the royal couple visited the expansive Dale Estate greenhouses in Brampton, known as the “Flower Town of Canada.” William’s two sons had married two Dale sisters, and when the sisters’ father died, William became one of the trustees of the thriving business.

During this time, William travelled widely, taking part in trade missions and lecturing on economics. In 1912, while visiting Britain, he planned to travel home on the maiden voyage of the newly built coal-powered steamship Titanic. But a country-wide coalminers’ strike had put the fabled liner’s coal supply in doubt, and fearing potential delays, he fortuitously purchased tickets for passage on an earlier boat.

Shortly after Mark Twain’s death in 1910, it was discovered that the American novelist, travel writer, lecturer, humorist and – evidently – hoarder had stashed away thousands of letters written to him by readers. In 2013, R. Kent Rasmussen curated 200 letters from Twain’s legions of fans – and foes. Dear Mark Twain includes correspondence from farmers, schoolteachers, children, preachers, a former president of the United States, inmates of mental institutions, con artists … and one William Algie of Alton, Ontario. Not surprisingly, given William’s secular leanings, his letter praised an article in which Twain called the holier-than-thou rector of a New York church “a crawling, slimy, sanctimonious, self-righteous reptile.”

In 1914, William died suddenly at age 63 from an acute attack of indigestion. Belying his rather diminutive gravestone, his funeral was a huge event. Local businesses closed and throngs of people paid their respects. A special CPR train carried family, colleagues and friends to Alton from far and wide.

Robert spoke at his brother’s graveside: “He lived a useful, active, busy life. The world is better for his having lived, and in passing leaves behind the memory of an honest, brave, intrepid man who bowed alone to death. In conclusion, might I add that if everyone to whom he has done some kindly, generous act were to bring a blossom to this grave, he would sleep tonight beneath a wilderness of flowers.”

More Info

Bred in the Bone

William was not the only member of the Algie clan to make headlines in service to their community and country. His brother James graduated from Trinity Medical School at the remarkably young age of 20 and was licensed to practise in 1878. In 1881, James opened his Alton practice on Queen Street, next to the Algie Bros. general store.

As a young doctor in Alton, James found himself treating his older brother Matthew for “inflammation and obstruction of the bowels.” Tragically, the illness proved fatal. Matthew died in 1884, still in his 20s.

In that same year, James was named Caledon Township’s first medical officer. Perhaps his experience with Matthew – and others in the village – inspired him to delve into many of the township’s poor sanitation habits. He tested and proved that animal pens and outhouses built too close to the river and to drinking wells were contaminating water sources and causing serious illnesses. His efforts to change these practices had a profound effect on Caledon and helped end the spread of many deadly diseases.

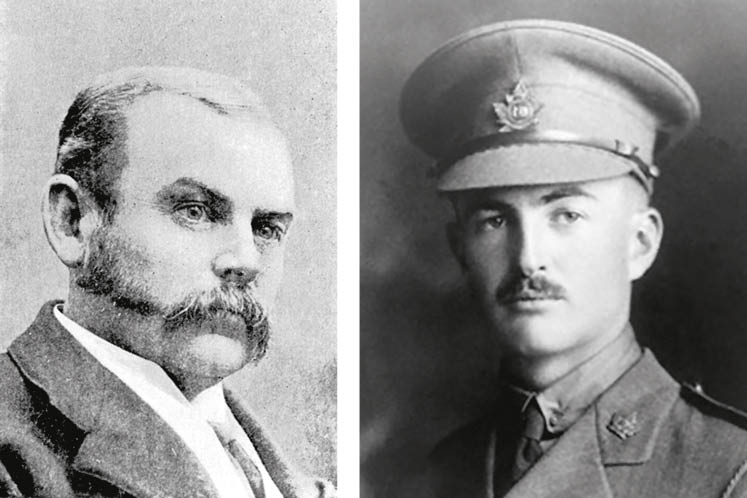

William Algie’s brother, James Algie (left) was Caledon Township’s first medical officer. James’ son, Wallace Lloyd Algie (right) was awarded the Victoria Cross after he was killed during a mission in France in 1918.

James was also a writer. Under the pen name Wallace Lloyd, he wrote three well-received novels: Houses of Glass: A Romance, Bergen Worth and The Sword of Glenvohr. A review in Toronto’s Globe newspaper described his books as “bright, piquant, and interesting.”

Like his brothers, James loved and excelled in music, the arts and sports. He was a member of the Alton band and enthusiastically supported the Alton baseball team. Robert, who was a few years younger than William and James, played first base during the team’s glory years in the 1890s and managed the team.

Sadly, James’s only son, Lieutenant Wallace Lloyd Algie, was killed in action in 1918, exactly a month before the armistice was signed. Near Cambrai, France, German machine gunners in and near a neighbouring village had been raking the Canadian position with relentless fire. Lloyd, as he was known to family and friends, and nine soldiers under his command volunteered to clear the machine gun nests. Though the mission was successful and the Canadians captured the village, Lloyd was killed during the operation.

His efforts earned him the Victoria Cross, the highest British military award for valour (a British honour because, at the time, Canadian forces were under the command of the British). The Royal Canadian Legion, Alton Branch 449 Lt Algie VC, is named in Lloyd’s honour. His citation says, “For most conspicuous bravery and self-sacrifice, on the 11th October, 1918 … His valour and personal initiative in the face of intense fire saved many lives and enabled the position to be held.”

William Algie’s brother, James Algie (left) was Caledon Township’s first medical officer. James’ son, Wallace Lloyd Algie (right) was awarded the Victoria Cross after he was killed during a mission in France in 1918.

Related Stories

The Party that Grew: Drummers’ Snack

Mar 23, 2008 | | Historic Hills“We did not see a drunken man on the grounds,” observed the Advocate (although the paper did wonder who rang the park bell at 6 a.m. on Saturday morning).

Dr. Algie Delivers a Jolt

Mar 23, 2011 | | Historic HillsBy the 1880s, poor sanitation had been identified as a major cause of disease and governments were taking action. Here in the hills, newly established health boards had a lot of catching up to do.

The Night the Dams Broke

Mar 18, 1999 | | HeritageTwo hours before dawn, on November 13, 1889, the great Alton flood disaster took place when a series of dams failed to hold strong.

The Alton Mill: New Life for an Old Mill

Sep 15, 2008 | | Back IssuesIt has been a long and costly labour of love, but Jeremy and Jordan Grant are set to unveil their landmark restoration of the Alton Mill.