Dr. Algie Delivers a Jolt

By the 1880s, poor sanitation had been identified as a major cause of disease and governments were taking action. Here in the hills, newly established health boards had a lot of catching up to do.

On sultry July afternoons, it was Bill MacDonald’s habit to get his cane and walk over to the Belfountain post office. His excuse was to pick up the mail, but the real reason was that the post office was in Charlie Byam’s store and the canvas awnings over the big windows made it cool there. More important, Charlie’s was a good place to hang out, to lean against the flour barrels and catch up on local gossip.

When Bill made his customary visit on an especially hot day in 1891, he found much to talk about. Dr. James Algie, medical officer for Caledon Township, had just analyzed the village’s drinking water and his report, nailed to the wall of the post office, was a shocker.

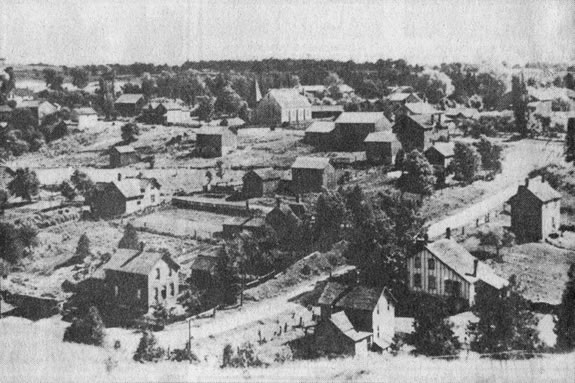

Almost every resident of Belfountain drew drinking water from a stream that ran through the village. It meandered by a number of privies, flowed around a manure pile, ran under the floor of a blacksmith shop and then filled a large tank on its way to the Credit River.

Dr. Algie had sampled the water at three points. He noted that on the day of his analysis a cow was standing in the stream and two pigs had settled in for an afternoon snooze. The results made for absorbing reading.

The first sample, taken near the source west of the village, Algie rated as “fairly good.” The second, in mid-village, was laced with animal hair, feces and Paris Green (a widely used pesticide). He called it “bad.” The third sample, taken from the main supply tank at the east end of Belfountain, he called “poisonous.”

Not just in Belfountain

Algie focussed on Belfountain because of a typhoid fever epidemic in the village during the fall of 1890, but the little escarpment community was far from unique. Inglewood, Cataract and Credit Forks had also recorded deaths from typhoid that year, all traced to bad water.

In the northwest corner of Caledon Township and into the adjoining portions of Erin Township, Algie reported a rate of typhoid that “has not been equalled for years.” Bolton, by contrast, appeared to be relatively free of typhoid, but as if to compensate, tuberculosis had raised its ugly head. Of the forty-six deaths from TB recorded in all of Peel in 1891, three were from a single Bolton family. Farther north in Dufferin, Shelburne reported both typhoid and diphtheria and, as elsewhere in the hills, a slight increase in the incidence of scarlet fever.

In Orangeville, however, the disease rate was much lower. Back in 1876, well before boards of health were common in Ontario, the town had set up a health committee that had immediately tackled the problem of backyards full of manure, exposed privies and piles of garbage. Offenders were given three days to clean up.

The need to change bad habits

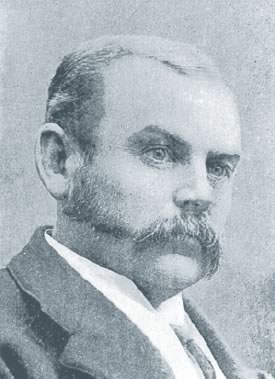

When Dr. Algie graduated in 1878 from Trinity Medical College in Toronto, pioneers in hygiene such as Joseph Lister and Louis Pasteur had already proven the powerful connection between health and sanitation, but the impact of their work had yet to penetrate the public mind.

Some urban communities, with their denser living quarters, had established boards and bylaws to regulate garbage disposal and privy location, but these were haphazard at best and more a matter of odour prevention than hygiene. (The Orangeville Sun lauded the town’s health committee for ridding the town of “backyards fetid with exhalations from decomposing refuse.”) Small rural communities and farms had no controls at all.

There was a time when pioneer families and the residents of small hamlets could rely on the natural cleaning forces of nature. Both Erin and Caledon East, for example, are thought to have benefitted from their fast-flowing streams. But as populations increased, that natural benefit diminished. Private backyard butchering was being replaced by commercial slaughterhouses invariably located by streams where operators could dump the offal. Not just on farms but in towns and villages, most citizens kept pigs and chickens, usually in pens that were aging, cleaned irregularly if at all and, as often as not, built near the water supply. No stream could move full and fast enough to flush away the detritus of a steadily growing population. Here in the hills and elsewhere it was time for change.

When Ontario’s public health act was passed in 1884, James Algie had been practising in Alton for three years and fully embraced his appointment as township medical officer. In his very first report he singled out Alton, Caledon East, Charleston (Caledon Village), Mono Mills and Belfountain with a stinging condemnation of local habits. The casual “throwing out of table refuse and spoils,” he said, turned backyards into “perfect cesspools.”

Also under fire were hog pens that went uncleaned for months, privies that were never cleaned at all, and cellars full of rotten vegetables. Algie came down especially hard on Credit Forks for its “hot-beds of filth” and for the community’s failure to respond to cleanup orders. Drinking-water supply was a hot issue for him as Belfountain discovered. He even joined forces with Erin Township’s medical officer, Dr. McKinnon, to put the heat on Hillsburgh where typhoid was a serious problem. Nor did the good doctor hesitate to name names, blaming a typhoid outbreak in Credit Forks on the “filth heap” from a large boarding house.

A positive effect

Dr. Algie’s efforts had powerful results. In Alton, he had pushed for the removal of a slaughterhouse located near a well used by five families. Among them there had been three deaths over a short period from croup and diphtheria. When the slaughter-house disappeared so did the diseases.

In Cataract, where scarlet fever had been rampant, a cleanup turned things around. And in Belfountain? Within two years its citizens had wholly embraced the notion of drinking water from properly sited wells. By the end of the century, Peel generally and Caledon specifically were able to point to these and other shining examples of change.

Not that things became perfect. More than a century later in the sad development at Walkerton, the whole world was to learn yet again that when it comes to hygiene, especially drinking water, there can be no let-up in vigilance. James Algie insisted on that.

____________________

The need for a community authority

Before municipal health boards were established, there was no one in charge of health-related matters. A striking example of this vacuum is evident in the July 1874 issue of the Orangeville Sun. Editor John Foley reported that “a disagreeable stench, emanating from the putrid carcass of a horse, was permeating the atmosphere by Central School.” He lamented that because no one had a duty to remove it, the situation would not improve until the carcass rotted away naturally.

____________________

Algie tackles “la grippe”

While the threat of typhoid fever, diphtheria and cholera raised alarm bells, intestinal diseases were regarded simply as an unpleasant fact of life. These varied from serious cases of enteritis and dysentery to less debilitating illnesses with names like “stomach complaint,” “green apple gallop,” and “privy trot.” Dr. Algie, who used the encompassing French term, “la grippe,” was especially successful in demonstrating to Caledon’s citizens that poor sanitation and inattention to hygiene were a prominent cause of these potentially harmful conditions.