The Story of a Mill

Mono’s Sheldon Creek was the site of one of Ontario’s two longest-serving waterpowered mills.

In 1822, the survey of Mono Township was barely complete when Joe Alexander came upon a nameless creek north of the Hockley valley and knew he’d found the place to build a mill. The reliable little waterway eventually came to be called Sheldon Creek, and the hamlet that grew up around Joe’s mill eventually became known as Sheldon – after living through such less felicitous names as Pigtown and Gutter Gap.

NOTE (March 20, 2010): an UPDATE to this story is appended below.

Mark Nelson as a young man. He was born in the miller’s house at Sheldon Creek. He purchased a stone house on the adjoining acreage. The family sold the property shortly after the mill burned down in 1963.

As for the mill, Joe’s decision proved to be a sound one. The enterprise would go on to outlast the community’s several names and even the community itself. From the mid-1820s through the next 140 years, the Sheldon mill on the Mono-Adjala Town Line served faithfully and well. When its long life came to an abrupt halt in 1963, only one other waterpowered mill in all of Ontario could lay claim to a longer history of continuous operation.

Sadly, Joe Alexander never got to see the proof of his vision. In 1832, he undertook the daunting trek to Toronto (then still York) and on to Hamilton for equipment to upgrade the operation. His timing could not have been worse. That was the year a cholera pandemic, after first decimating Montreal, swept into the major towns of Upper Canada. Joe made it back to the hills just in time to die. He was only thirty-three. The mill he founded lasted another 131 years, but finally met its demise on June 27, 1963, when a fire of unknown origin burned the venerable building to the ground.

The Community’s Heart and Soul

Those 131 years were productive ones, meaningful not just for the mill itself and the families who operated it, but for the community that grew up next door and the farmers who came for miles from the west in Mono and from the east in Adjala.

For much of its life, the Sheldon mill was a grist or “chopping” mill, grinding grain to feed livestock, but in the earlier years it also milled grain into f lour, a service vital to the lifestyle, even the very survival of the first settlers.

In Upper Canada, families without access to facilities like the Sheldon mill had to struggle with mortarand- pestle methods to make flour, using hollow stumps or flat rocks, and then straining the chunky result through sieves made of horsehair and the like.

So important was genuinely milled flour that great effort was expended to get it and Mono provides a good example. Its long hills were often too steep for oxen to haul up grain on what passed for roads. Thus, many a farmer on his way to Sheldon left his team at the bottom of a hill and carried up the bags of grain on his back.

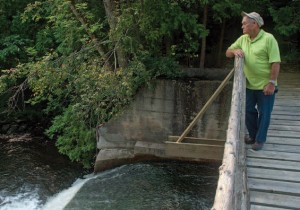

Nelson, now 86, continues to live nearby and still visits his former home. Below he surveys the mill dam from the bridge he helped his father build.

Once a country mill was up and running, commerce invariably followed and Sheldon was typical. By 1870, the community had a store, blacksmith, planing mill and shoemaker, along with a post office, tavern and Orange Lodge (LOL 1083: meetings on first Monday b.f.m. – before full moon).

An Enduring Family Enterprise

It is not certain who ran the mill immediately following the death of Joe Alexander, but after 1845 its story is one of long-term family management and rock solid dependability.

The Newells ran it until 1865 when the Parker family from Alton took over for the next three decades. In the Parker era, the limited number of mills in Mono and Adjala meant that the more distant farmers had a two to three day trek to get to Sheldon. Particularly after the harvest, when many showed up at the same time the lineup turned the Parker’s kitchen and barn into a quasi-hotel as customers waited overnight and longer for their turn. This phenomenon likely explains why yet another name used for Sheldon was Parker’s Mill.

Alfred Smith bought the mill in 1896, setting up a long run of twentythree years. In 1914, he hired young Wilfred Nelson, a decision that was to begin the longest tenure in the mill’s history. Within five years Wilfred had not only become the miller, he bought the place and, by the night of the fire in 1963, he was into his fiftieth year at the mill. During that half century, Wilfred and his family were witnesses to the winding down of an era, and to the dramatic changes in milling introduced in the twentieth century.

A Mill No More

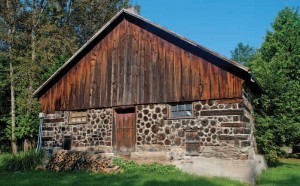

The Nelsons used this unusual cedar-block barn, c1834, as a piggery. It still stands on the property.

Wilfred’s two sons Allan and Mark became part of the operation at a young age. Today, Mark, an active and robust 86 year old, remembers well his early days at the mill.

“I was fourteen,” he says, “going to continuation school over on the Seventh Line of Mono, grade nine at the Union School there. But that year I got measles, mumps, whooping cough and scarlet fever, and couldn’t write the exams. So there I was. In the mill.”

By Mark’s time, the mill at Sheldon was a long stride away from its beginnings.

“There were no such things as millstones anymore,” Mark recalls, “though I still remember the old stones lying in the yard. And the days of grinding flour were pretty much gone too; the big mills took that over. By the thirties we were basically a chopping mill. The turbine was still water powered though and we controlled our own dam. There had been a water wheel at first, but that was long gone by my time.”

Not only was the water wheel gone, and the milling of flour, but by this time many customers were serviced from home. The Nelsons would pick up grain by truck and then return it as chop.

“A lot of our grain was coming into Alliston in bulk by rail,” Mark explains. “We’d go to the station, bag it and bring it home.”

The modern building, with its decorative mill wheel, was built by the current owners on the foundation of the original mill.

It seems his journey through childhood disease had left Mark no worse for wear. He had no trouble hefting the 150 pound bags of wheat. Nor was he impeded by such trifles as a driver’s licence, although in 1939, after driving to and from Alliston for two years, he finally did get one. That probably helped once the Nelsons were going all the way to Collingwood to pick up bulk grain from the elevators there.

Mark’s brother Allan had become the miller by the time of the f ire in 1963, although Wilfred and other Nelsons were still very much involved. The family’s decision not to rebuild, but rather to bring the long and successful enterprise to a close, was emotional but practical.

Competition, particularly from larger mills, had become intense and widespread. The needs and practices of modern farming had raced beyond what a small, rural, independent mill could provide.

Sheldon itself had gradually disappeared. The store was closed, and the planing mill was gone, along with the shoemaker and blacksmith. Even the Orange Lodge had moved to Relessey. It was almost as if the old mill had spoken from the ashes: “I’ve had a great run, but now it’s over.”

*****

EQUAL IN THE EYES OF GOD (AND MILLERS )

For years, the Mono-Adjala Town Line was somewhat notorious as a sharp divide between Catholic and Protestant territory: Green to the east, Orange to the west. Yet when Barney Nelles from Adjala once showed up at the mill, on the 12th of July of all days, with grain that he urgently needed chopped, Wilfred Nelson, who’d never missed an Orange Parade in his adult life, took off his suit, put on his miller’s coveralls and opened the mill race. In Sheldon, it seems a Catholic farmer could rely on a Protestant miller no matter what the day.

A ROSE BY ANY OTHER NAME …

Adjala is reputed to be the name of Tecumseh’s daughter, but there’s no evidence the famous chief ever had a daughter. Mono, now the Town of Mono, is supposedly from an aboriginal language or possibly a Gaelic one. The origins of the “Sheldon” name are equally murky. When the first post office opened there in 1867 (closed 1915), the community was still called Gutter Gap or Pigtown or, by some, Parker’s Mill. In the nineteenth century, when a community got a post office, authorities would often assign a new name arbitrarily, mostly to avoid confusion, but also if they simply did not like an existing one. It’s entirely possible Sheldon was simply labelled by Ottawa.

VERY HOT AND VERY DRY

These hills sizzled in the summer of 1963, with record heat and little rain. At the time of the Sheldon fire at the end of June, there were water shortages everywhere. Temperatures steadied at +35°C and higher over the holiday weekend. Horses collapsed at the Orangeville Raceway and the town enacted water restrictions against lawn watering, car washing and even urged against flushing of toilets. The threat of uncontrolled fires had officials on edge, and the blaze at Sheldon along with a number of other disastrous fires justified their fears.

UPDATE (March 20, 2010)

THE STORY OF A MILL REVISITED: A TALE OF TRUE LOVE

In the original story of Mono’s Sheldon Creek Mill (“The Story of a Mill,” Autumn 2009), a brief reference was made to the Newell family. Although the family ran the mill for twenty-five years, from 1840 to 1865, preliminary research turned up little information about them. Since the story appeared, however, descendants of the Newells have filled in details of an intriguing family history:

Sam Newell and his wife Anne grew up together in County Down, Ireland in dramatically different circumstances. According to family lore, Anne (b.1775) was the only daughter of Lord and Lady Thornbury, and Sam (b.1774) was a labourer on the estate. When Anne’s parents discovered the two were in love, they banned Sam from the property and, in effect, from employment in Ireland. In despair, he went first to England and then to North America. Anne, the story has it, crawled out a window one dark night, along with her maid, to follow her beloved Sam. When they married, she lost all claim to property and title.

While this narrative is difficult to verify, what is certain is that Sam and Anne arrived in Mono together in the 1820s and established a farm just south of the mill. In April 1840, they traded this farm plus some cash for the mill. When the mill’s founder, Joe Alexander, died of cholera in 1832, his widow was left with five children and another on the way. Although she struggled to keep the mill going over the next eight years (with Sam’s help, it is believed), it must have been a relief to trade for a farm.

Sam and Anne turned over the mill to their son John (and his thirteen children) in 1847 and enjoyed a few years of retirement. They are buried together in St. John’s cemetery on Mono’s Seventh Line. Sam died in January 1852. Anne followed him one last time, just six weeks later.

As in other comments on the story, I drove buy it yesterday on September 15, 2013 and found it to be quite picturesque and wonder what has become of the old mill. There is still more of the story that needs to be completed. I would love to learn more. I wanted to drive in, however I respect privacy and not sure if this is a private residence.

Randall McKeown from Mississauga on Sep 16, 2013 at 8:27 am |

We also drove past this site on May/11/13 Thought it may be an inn or restaurant . Anyone know?

Thanks

Frank O'Gorman on May 12, 2013 at 10:52 am |

Drove buy property today, stopped and backed up and sat for a few minutes, did not know anything about it until i got home and googled it. What a neat piece of history and a beautiful place, I wonder who owns it now.

ted crow on Apr 5, 2013 at 9:12 pm |