Coming of Age in the Sixties

The sun was resting on the limestone cliff, setting it ablaze. I squinted at the orange embers on the rock wall, but the reflection was so glaring, I had to look away. My childhood too had gone up in flames.

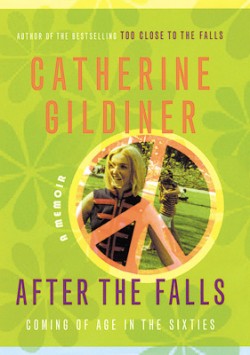

In After the Falls, the sequel to her bestselling childhood memoir, Too Close to the Falls, Creemore author Catherine Gildiner dissects a decade of personal and political turmoil with humour, honesty and insight.

Young Cathy McClure had no idea how idyllic her unconventional childhood in the leafy security of Lewiston had been, until it disappeared. But, as she embarked on adolescence in a new home, it wasn’t just the family fortunes that had changed, the wide world was changing too. In After the Falls, the sequel to her bestselling childhood memoir, Too Close to the Falls, Creemore author Catherine Gildiner dissects a decade of personal and political turmoil with humour, honesty and insight. The following excerpts are from the first chapter: Expulsion.

As we crept up the narrow winding road that rimmed the Niagara Escarpment in our two-toned grey Plymouth Fury with its huge fins and new car smell, my father pressed the push-button gear, forcing the car to leap up the steep incline and out of our old life. The radio was playing the Ventures’ hit “Walk Don’t Run.”

I sat in the front seat with my father while my mother sat in the back with Willie, the world’s most stupid dog. We were following the orange Allied moving van, and I kept rereading the motto on the back door: leave the worrying to us. Two tall steel exhaust pipes rose in the air like minarets from both sides of the truck’s cabin. Each had a flap that continually flipped open, belching black smoke and then snapping shut, like the mouth of Ollie, the dragon handpuppet on the Kukla, Fran and Ollie television show. The smoke mouths kept repeating the same phrase in unison: It’s all your fault … it’s all your fault.

I pressed my face to the window as the car crawled up the hill in first gear. Lewiston, where I’d grown up, was slowly receding. The town was nestled against the rock cliff of the huge escarpment on one side and bordered by the Niagara River on the other. St. Peter’s Catholic church spire, which cast such a huge shadow when you were in the town, was barely visible from up here.

The sun was resting on the limestone cliff, setting it ablaze. I squinted at the orange embers on the rock wall, but the reflection was so glaring, I had to look away. My childhood too had gone up in flames.

***

As the car chugged toward the top of the escarpment, I, like Lot’s wife, looked back at the town below me. I had no idea then that I was leaving behind the least-troubled years of my life. Strange, since I felt there was no way I could cause more trouble than I’d caused in Lewiston.

It was 1960. We were doing what millions of other people had done: we were migrating. The Okies had left the Dust Bowl for water and we were leaving Lewiston for what my mother had mysteriously described as “opportunities.” Whatever the reason, we were leaving behind the chunk of rock that was a part of us.

What would I do in Buffalo in the summer heat? When I was working at my dad’s store in Niagara Falls, I would wander over to the falls and get cooled off by the spray. I couldn’t imagine not being near the rising clouds of mist that parted to reveal the perpetually optimistic rainbow.

What would my life be without the falls to ground me? Losing the falls was bad enough, but how could I leave the small, idyllic town of Lewiston, where history was around every corner? General Brock had been billeted in our house during the war of 1812. Our basement had been part of the Underground Railroad that smuggled black slaves to Canada. And would I ever again live somewhere where everyone knew me – where I knew who I was? I would no longer be the little girl who worked in her dad’s drugstore. Roy, the delivery driver with whom I distributed drugs all over the Niagara Frontier, used to say if someone in Lewiston didn’t know us, then they were “drifters.”

***

Soon the escarpment was only a line in the distance, and Lewiston had disappeared. I would always remember it frozen in time: the uneven bricks of Center Street under my feet; the old train track up the middle, worn down after not being used for almost a century; The Frontier House, the hotel where Dickens, James Fenimore Cooper and Lafayette stayed and the word cocktail was invented; the maple and elm trees that arched over the roads, and the Niagara River, with its swirling blue waters that snaked along the edge of town.

As we began to head south, I thought about the tightrope walker my mother and I had seen, years ago, inching across Niagara Falls carrying a long balance pole. We stood below on the lip of the escarpment, holding our breath. My mother kept her eyes shut and made me tell her what was happening.

I felt as though now, as I headed into my teenage years, it would take all I had to maintain my balance. I knew the secret was to never look down at the whirlpools below, to focus on a fixed point at eye level and keep moving. I had no idea then how much I would teeter when the winds of change in the 1960s got blowing.

***

When my father had announced the move, he said we were going for “new business prospects.” He said that the economy had changed and that pretty soon there wouldn’t be any more small, family-run drugstores. I had never thought our drugstore was small – I thought of it as enormous. He maintained that the world was being taken over by “chain stores.” I didn’t know what these were; I thought at first that he meant hardware stores that sold shackles. He explained how chain stores worked out better prices from the drug companies, how they didn’t make specialty unguents and didn’t deliver. Most of the work was done by pharmacy assistants. He could no longer compete; it was time to get out before we were forced out.

Did he really think these chain-type-stores would catch on? Had he forgotten about loyalty? I thought of all the times Roy and I had risked our lives delivering medication on roads with blowing snow and black ice, or worked after midnight to get someone insulin. It was my father who always said that customers would appreciate the service and be loyal. But just days ago, when I’d questioned him on this, he said that people could be fickle and that their loyalty was to the almighty dollar. All the service in the world couldn’t keep a customer if Aspirin is cheaper elsewhere.

When I said that was terribly unfair, he pointed out that that was just human nature. People did what was best for themselves at any given time. I’d never heard him speak so harshly. He’d usually espoused kindness and “going the extra mile.” He put his arm around me and said that the world was changing and it was best to move on. You couldn’t stop progress. After all, America hailed the Model T; no one cried for the blacksmith.

As we drove along the ugly, detour highway, weaving between gigantic rust-coloured generators that obscured the view of the rock cliffs and the river, I asked why, since we must be getting near the city of Niagara Falls, we didn’t see the silver mist of the falls spraying in the air like a geyser. My father told me the highway we were on was being built by Robert Moses (who would coincidentally name it the Robert Moses Parkway, though I never saw a park). Moses designed it so that tourists would be diverted from the downtown core of Niagara Falls and forced to drive by his monument of progress, the Niagara Power Project. No one would drive through the heart of Niagara Falls any more, which is where our drugstore was. My father predicted, accurately as it turned out, that the downtown would soon die.

~~

After about a half-hour, my father circled off the New York State Thruway onto a futuristic round basket-weave exit marked Amherst. “Wait until you see how convenient this home is for getting on the highway and travelling,” he said.

I wondered where we would be going since my father said travelling spread disease.

A minute later he swung into a suburban housing development with a sign that read kingsgate village, and then onto Pearce Drive. When he turned into a driveway, I was too taken aback to say anything. In front of us was a tiny green clapboard bungalow with pink trim. All around it were identical houses with slightly different frontispieces. My father had picked out this place, but I felt his mortification at having to show it to us. It started to sink in that our historical colonial home with the huge wraparound porch was now history.

Why my mother had not been included in the house hunt was a mystery to me. It wasn’t like she was busy. She’d never in my memory cooked, cleaned or held a job.

She was trying to find nice things to say. “Well, this should be easy to look after. No big yard to rake.”

But I could feel her slowly withering, cell by disappointed cell.

***

The moving van pulled up. As one mover chomped on a hoagie, the other jumped down from the cab, looked at the house and said to my father, “There’s no way you are ever going to fit these huge pieces of furniture into this place. What am I supposed to do with them?” The front door was obviously too narrow for the French armoires and early American dressers.

My father said nothing. I had never seen him look as though he was not in charge. He just went and sat on the porch, which was actually a cement stoop. My mother, who’d inherited these antiques and cherished them, ordered the movers to unload everything onto the driveway. Then she said to my father, “Not to worry, Jim. Some of these things have been in my family for far too long. It’s progress – we’ll clear out some of it – deadwood.”

***

Once the weensy rooms were filled, my father, bewildered, stared at the ocean of antiques in the driveway. He said to my mother, “When I saw this place it was empty. I don’t remember it being so small.”

My mother refused to watch as the movers hoisted the furniture into the attic of the garage. Marble tabletops were removed with crowbars and stored in pieces. Most of the pieces would eventually warp from freezing temperatures and moisture. My parents would never sell them or look at them again.

***

My father was always affable with the neighbours, talking over identical chain-link fences in the summer about chlorine tablets for above-ground pools and lawn mowers. Although my father was always friendly, most of the people on the street were younger. Our house was, as they say in the real estate world, “a starter home.” Though for my parents it would be a finishing home – hardly bigger than the wooden caskets they would be carried out in.

In Lewiston my father had been used to giving out advice. People had come to him because he was the town pharmacist; he had a position in the church and community and he knew things. Here in Buffalo, people got advice from “Dear Abby.” They weren’t going to go to some washed-up old pharmacist. I noticed that he now exaggerated. I heard him telling a neighbour that I was New York State’s high jumping champion, when in fact my title was only for western New York and my record was beaten before I even had a chance to get new track shoes.

My parents adapted to their new circumstances in their own way. My father bought a recliner in leatherette, smoked and watched television. He went to work for a large drug company. He described his research team as though it were the Manhattan Project; however, when I went to his building, which took up nearly a city block, people seemed to hardly know him.

My mother didn’t do a thing with the house – she never even changed the carpets. She always acted like she was staying in a déclassé hotel. The only problem was that there was no room service. If she ever wondered how a college educated woman who was also a master bridge player wound up on Pearce Drive, she never once asked me.

Their new church was huge and they went unnoticed there. People didn’t walk to church in Buffalo as they had in Lewiston. And no one waited around after church to go out together for brunch. Everyone drove to church and then, after Mass, they got in their cars and, with an altar boy directing traffic, filed out of the parking lot as though they were in a funeral procession.

***

Catherine Gildiner is already at work on the third volume of her memoirs, The Long Way Home, documenting her university years, fi rst at Oxford and then, in 1970, at the University of Toronto’s Victoria College where she undertook post-graduate studies in English Literature before pursuing her career as a clinical psychologist. Photo by MK Lynde.

Within the first few weeks of our arrival my mother and I began to venture out in our Plymouth Fury on reconnaissance missions. We decided to spread our wings a few blocks at a time. We needed to know exactly how bad it was. There were no sidewalks on the major streets, so we never saw people out strolling. The stores all had names that were so unoriginal as to be almost laughable. The convenience store was a chain called Your Convenience. The florist was called Flowers ’n’ Things. Most of the stores were chains and seemed to be full of minimum-wage employees.

Once we ventured out of our cloned subdivision, which my mother and I clandestinely referred to as Tiny Town, I noticed that there was a positive correlation between distance away from Pearce Drive and how big the houses were. The majority were large, elegant brick homes with manicured lawns and built-in pools. Some were mansions with guest houses and elaborate gardens.

My father’s decision to move to Tiny Town was slowly starting to make sense. When I was kicked out of Catholic school in Lewiston, Father Rodwick, the jejune Jesuit who had been my religious-instruction teacher, recommended the school in Amherst to my mother for its great advanced program. My father must have bought the only house he could afford in this swanky school district.

***

I felt a bit sorry for my parents. I knew I was not going to study any harder here than I had in the past. Father Rodwick thought he’d discovered someone with special intelligence. He was wrong. I was only experiencing a motivational blip. A girl will do anything to catch the eye of a handsome man. But there was no point in telling my parents about my prophecy of academic mediocrity. They would get the drift soon enough.