Alexander McLachlan: Our Forgotten Poet

A century ago Alexander McLachlan was one of the best known citizens of these hills, widely admired, respected and praised for his poetry. Today hardly anyone has heard of him. How did this happen?

When he came to Canada from Scotland in 1840, Alexander McLachlan was 22 years old and had no plan to be a poet. He had often dabbled in verse during his apprenticeship as a tailor, but that was a common diversion of the time. His plan, when he inherited his late father’s land near Rockside in Caledon Township, was to take it over and farm it. However, like his hero, Scottish poet Robert Burns, McLachlan never could seem to make it as a farmer.

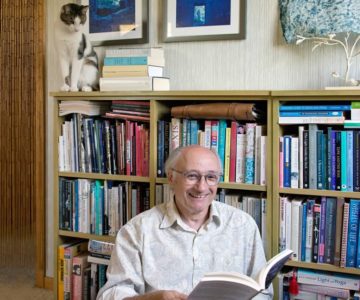

Alexander McLachlan (1818–96)

In 1890, this portrait was presented to McLachlan at a tribute dinner. In 1967, it was reportedly found in rubble behind the furnace at the Orangeville Public Library.

In 1841, he married his cousin Clamina, sold half the Caledon property, moved to what is today Perth County, and over the next dozen years failed to make a go of two different farms. That likely explains why, in 1853, he and Clamina with their growing family (eventually to number 11 children) finally settled on a one-acre lot near the village of Erin. By now Alexander was gaining recognition for his poetry, but for financial security he was also relying on his early training as a tailor.

Farming would enter the picture again much later in 1877, this time on a hundred acres in Amaranth Township. By all accounts his farming skills had not improved, but by this time Alexander McLachlan was a big name, for during his years in Erin Township he had become a genuinely famous poet. Not a wealthy one – more on that later – but as early as the 1860s, he was an established man of note.

A man of note

Two newspaper columns, years apart, offer some evidence of McLachlan’s stature in his day. In February 1872, the Orangeville Sun reprinted a lengthy review of his work by E.H. Dewart, a clergyman and prominent literary critic. In his 1864 anthology, Selections from the Canadian Poets, Dewart declared, “McLachlan, the gearless tailor of Erin, deserves to be among the recognized spiritual kings of the age like Shakespeare, Byron, and Schiller.” Lofty praise indeed, but by then such praise had become common in describing the poet.

In April 1890, Toronto’s Globe newspaper quoted equally lavish comments in its report of a banquet held at the city’s posh Walker House hotel where a literary who’s who had gathered. Academics, dignitaries and executives of a number of Scottish brotherhoods lavished accolades (along with a commissioned portrait and a pile of money) on the guest of honour, Alexander McLachlan.

His lectures and frequent poetry readings were celebrated events everywhere they were held, not just in Canada but internationally, and newspapers reported on them with enthusiasm, spreading his fame even farther. At that 1890 dinner, his most recent volume of poetry was already 16 years old, exemplifying his staying power. And the purse he received ($2,100) was built with funds donated by fans from all over Canada, as well as the United States and Scotland. Alexander McLachlan – poet, lecturer, philosopher, farmer, tailor and citizen of our hills – was an international literary star.

A relatively modest output

McLachlan’s lifetime work, aside from single poems in magazines and journals, appears in just five bound volumes, the first in 1846 was a self-published 36-page pamphlet. His first volume of marketable consequence came out in 1856 under the restrained title Poems. His second volume, Lyrics, was published in 1858, while the very popular The Emigrant and Other Poems appeared in 1861. Together these three publications offered just 130 poems, and in his last and most substantial volume, Poems and Songs, in 1874, there are only 96, many of which had already appeared in magazines or journals. In all they represented less than a third of the output of the prolific Robbie Burns.

His contributions to magazines, of which there were many, were important to McLachlan not only as an important supplement to his income, but for their worth in solidifying his reputation. In publications such as Saturday Night and Canadian Monthly, his poetry praised citizens who supported themselves with their own labour. In the Scottish American, he painted Canada as a land where someone had the freedom to grow. In over 50 poems in Grip, a weekly satirical magazine, McLachlan took pokes at what he felt were the shortcomings of church and state. Taken together, these poems demonstrated both the breadth of his talent and the range of subject matter, serving to keep his name before a wider readership.

What was so special about his poetry?

Any artist who catches a wave is lucky, and Alexander McLachlan caught three. For one, the 19th century was a golden age for poetry in the Western world, so his audience was primed and ready. A second wave rose here at home where his work was especially sweet music to Canadian ears, for McLachlan wrote often about the unlimited opportunity for self-reliant pioneers in this new land. (“A Backwoods Hero” in which he champions Daniel McMillan, the reputed founder of Erin village, is typical.)

His Canadian audience called McLachlan their “pioneer poet,” a phrase cemented by the popularity of “The Emigrant,” a poem that became a standard at recitals. It also pointed directly to the third and most influential wave McLachlan rode: the Robert Burns factor. The similarity of McLachlan’s work to that of Scotland’s legendary poet and popular folk hero was such that throughout his career and long after his death, he was known as the Robert Burns of Canada.

The Burns factor

The unshakeable comparison to Burns was a badge – and arguably a stigma – that lifted McLachlan’s star to fame not just in Canada where Scottish culture and heritage was pervasive at the time, but internationally as well. There was much to connect the two poets. Their language is lyrical and the influence of Scottish dialect obvious. They both wrote for plain folk and paid careful attention to rhythm and rhyme. And both were deeply touched by simple events their audiences readily understood – Burns, for example, when he addressed the “wee, sleekit, cow’rin, timorous beastie” of a mouse whose nest he had plowed up, and McLachlan when he eulogized his dead ox as “the hero of the field … I ne’er could think thou wert a brute, but just a silent brother!”

Also mutual was their belief in human and civil rights. In his “Address of Beelzebub,” Burns lamented the oppression in Scotland that forced tenants to flee to “the wilds of Canada.” In “The Emigrant,” McLachlan explained why he fled to those wilds. And in such poems as “The Man Who Rose from Nothing” he went on to elaborate why the wilds were preferable because they offered freedom and choice. That the two poets would be compared was inevitable, but perhaps because Burns came first and was far more established, McLachlan remained in his shadow.

So why have we forgotten him?

Could it be the Burns factor? During his productive time, McLachlan appears to have been entirely content to be a lesser partner. On tour in Scotland and the U.S. it seems he readily accepted introduction as a Scoto-Canadian or, inevitably, the Robert Burns of Canada. At poetry recitals, which were regular events in our hills and elsewhere in the 1800s, even though the point of the evening was his own poetry, McLachlan read from Burns’ work so regularly that newspapers highlighted that as the feature of the night.

Today, Burns’ own star mostly shines just once a year on January 25, when Robbie Burns Day suppers are held to celebrate his birthday, but there is no similar McLachlan Day tradition to keep the Canadian poet’s star from dimming.

Not just the Burns factor

McLachlan’s stature may also suffer from a lingering Canadian tendency to forget or ignore our own. In 1961, for example, on the anniversary of his death, the Toronto Star buried a short piece in the bottom of a back section under the headline “Dufferin Farmer Wrote Verse in Burns Tradition.” By comparison, just a few years later, on the 150th anniversary of McLachlan’s birth, a Scottish newspaper, the Johnstone Advertiser, ran a full-page memorial under the headline “The Patriot Poet of Canada.”

Also, unlike Burns and his notorious escapades with women (he illegitimately fathered at least three children), there was no whiff of scandal about McLachlan to embellish his legend. His long and contented marriage to Clamina was not the kind to tickle gossip. What was publicly known were the chronic financial difficulties he endured throughout his career. In the 1870s, a fundraiser for McLachlan was openly initiated here in the hills by a letter to the editor from a resident of Mono, and the purse he received in 1890 was explicitly presented as financial relief. But it’s rare for poverty to burnish celebrity.

McLachlan was never a self-promoter, and though he once included a tribute from Susanna Moodie in one of his books, such behaviour was rare. He also had influential fans such as Fathers of Confederation George Brown and Thomas D’Arcy McGee, but he was not inclined to lean on them to boost his career. (In 1856 McGee arranged for McLachlan to be an emigrant agent in Scotland. On tours, McLachlan would read his poetry and then describe the wonders of pioneer life in Canada, telling Scottish audiences that winter is the best time of year.)

“His memory will be revered”

Still, it would be wrong to conclude that our poet of these hills has disappeared entirely. University of Toronto Press published a collection of his works in 1974 (calling him “an eminent though neglected figure”), and a British publisher, Forgotten Books, reissued much of his poetry in 2012. A brief skim of either publication confirms Alexander McLachlan deserves to be remembered.

A path to elevating that remembrance to the level it deserves might well be found in his obituary in the Orangeville Sun. After selling the Amaranth farm, Alexander and Clamina enjoyed a quiet year of retirement in their home on Elizabeth Street in Orangeville, where McLachlan died in 1896. On the occasion, Sun editor John Foley offered this summary and what he must have hoped would be a prediction: “While others strove for wealth and looked out for themselves, our poet spent his days in the nobler task of lightening the cares and lifting the burdens of his fellow men. His memory will be revered, as it ought to be, by generations yet unborn.”

Young Canada

Or,

Jack’s As Good’s His Master

I love this land of forest grand,

The land where labor’s free;

Let others roam away from home,

Be this the land for me!

Where no one moils and strains and toils

That snobs may thrive the faster,

But all are free as men should be,

And Jack’s as good’s his master!

Where none are slaves that lordly knaves

May idle all the year;

For rank and caste are of the past —

They’ll never flourish here!

And Jew or Turk, if he’ll but work,

Need never fear disaster;

He reaps the crop he sowed in hope,

For Jack’s as good’s his master.

Our aristocracy of toil

Have made us what you see,

The nobles of the forge and soil,

With ne’er a pedigree.

It makes one feel himself a man,

His very blood leaps faster,

Where wit or worth’s preferr’d to birth,

And Jack’s as good’s his master.

Here’s to the land of forests grand,

The land where labor’s free;

Let others roam away from home,

Be this the land for me!

For here ’tis plain the heart and brain,

The very soul, grow vaster,

Where men are free as they should be,

And Jack’s as good’s his master.

— Alexander McLachlan

Related Stories

Meet Harry Posner

Sep 16, 2017 | | ArtsDufferin County’s first poet laureate waxes eloquent on reclaiming the power of words and uniting our local arts community.

A Poetic Take on a Pest

Sep 18, 2020 | | EnvironmentCaledon poet Marilyn Boyle takes the gypsy moth caterpillar as her latest subject after her oak tree was decimated in the summer of 2020.

Day of the Poets

Mar 19, 2019 | | ArtsOrangeville’s festival promises to “saturate the air with poetry.”

Remembrance of Vimy Ridge

Mar 20, 2017 | | HeritageAmong Canada’s troops at Vimy was a young poet named Christopher George Cook.

Nellie and Winston

Jun 16, 2015 | | ArtsNellie and Winston remind us that even the most humble of these magnificent creatures deserve a place in our hearts.