Hurricane Hazel’s Place in Headwaters’ History

When Hurricane Hazel finally blew itself out in October 1954, the damage and casualties left behind made it Ontario’s biggest weather event of the century. The flood control plans that followed were even bigger.

Imagine standing on the northwest edge of Bolton looking up at a massive dam. The dam is 30 metres high. It is 500 metres wide and it converts the Humber River into a lake more than 7 kilometres long and as wide as a kilometre at some points. (Just in the spring, though. It’s a reservoir lake – more on that below.) Behind you, across town where the Humber emerges from Bolton’s southeast corner on its run to Lake Ontario, there is another lake. This one is 5.6 kilometres long, created by a dam at Nashville.

The lake that never was

In files at the Metropolitan Toronto and Region Conservation Authority (MTRCA, now TRCA) these two projects are identified as the Lower Bolton Dam and Reservoir and the Nashville Dam and Reservoir, part of a grand plan to control the Humber River watershed should another Hurricane Hazel ever visit the province.

The Humber flooded Bolton in 1950. TRCA documents at least 78 damaging floods on the river between the early settlement years and Hurricane Hazel, every two to three years on average.

A giant project

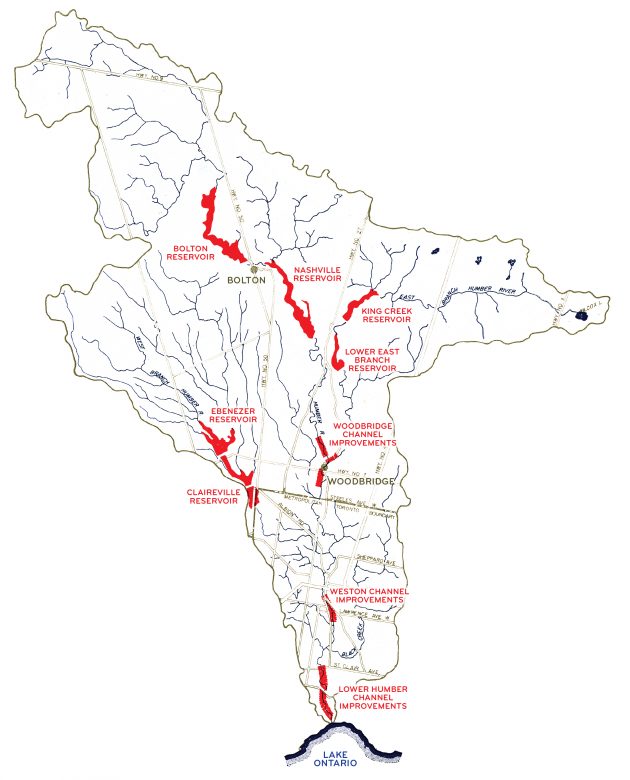

In June 1961, after six years of deliberation, many hydrological studies and much political exchange, the conservation authority approved a plan to build 13 dams in the watersheds of the Humber, Don and Rouge, the three main rivers that flow through Toronto into Lake Ontario. Six dams would be on the largest watershed, the Humber, each of them creating – and in theory controlling – a reservoir lake if and when a flood occurred. The dam on Bolton’s northwest edge, for example, an earth dam, would manage the water level of the Humber so that each spring, or in the event of a great storm, it could back up the river into a temporary lake, and so shield Bolton and communities downstream from flood damage. When conditions eased, the reservoir lake could be gradually lowered, returning the river again to – well, a river.

The grand plan also proposed stream straightening, removal of old mill dams, taking out homes near the riverbanks, and channel modifications to rejig the natural course of the river. This undertaking, especially along the Humber, would be big, expensive and disruptive.

The project underway

Three years later, the Claireville Dam on the Humber’s west branch (easily seen today from Highway 427 at Finch Avenue) was the first to be completed, coming in nearly on budget ($2.3 million). With memories of Hurricane Hazel still lingering powerfully in the minds of Southern Ontario citizens, the Claireville structure boosted public support for the flood control plan and, to an extent, muted alternative views at MTRCA, where not everyone agreed dam building was a good idea.

Support was boosted even further by the fact that land was set aside at Claireville for a conservation and recreation area. The dam project offered protection and promised fun. So there was little hesitation when plans solidified for the construction of three more dams over the next decade: on the Rouge at Markham, on the west branch of the Don near the intersection of Dufferin and Finch in Toronto and, the biggest of all the dams by far, on the main branch of the Humber at Bolton.

Two out of three

In 1973, the Rouge River’s Milne Dam and the Don River’s G. Ross Lord Dam were officially opened. That same year, on a table in Bolton’s community centre, MTRCA unveiled a scale model of the dam destined for the main branch of the Humber. Not that the Bolton dam had been ignored, for over the decade the authority had twice engaged in mass tree cutting along the Humber valley. But whereas the Milne and G. Ross Lord dams had enjoyed local support, the attitude of many citizens of Bolton and former Albion Township toward this third dam was less than enthusiastic, and not surprisingly so.

Unlike the two completed dams, the Bolton dam had no recreation features – no parks, no camping areas or hiking trails. Nor did it help when the authority said it merely “hoped” some kind of vegetation could be found to keep the Humber’s banks green when the lake was lowered. Another issue was the extra expense. Taxpayers would be footing the bill for a road over the Bolton dam because its $8 million budget didn’t cover that. These issues aside, however, what caused ordinary citizens to take a deep second breath was the dam’s sheer size.

Although six dams were planned for the Humber watershed, as shown on this MTRCA plan from 1959, only the Claireville Dam and a small dam on Black Creek were actually built. Click for larger map.

A clear and present danger?

It was impressive as an engineering project, but the feeling the Bolton dam created was uneasiness. Compared to the already completed structures this dam would be huge. As would the lake it created each spring, so large that to cross the Humber several kilometres upriver on 15 Sideroad (now Castlederg Sideroad) a four-span, high-level bridge would be required.

“The thought of a 90-foot wall of water at the edge of town sure didn’t make anybody comfortable,” remembers Emil Kolb, former chair of Peel Region and an Albion Township councillor at the time. “And the fact it was an earth dam bothered many people, too.”

At the unveiling of the scale model in 1973, Bolton reeve H.M. Allen summed up the general attitude when he told the authority’s engineers, “You have assured us the village will be safe. You better be right.”

It didn’t happen

The Lower Bolton Dam and Reservoir was scheduled to be completed in 1975. But it was never built. It wasn’t even started. Nor were any of the remaining reservoir dams specified in the grand plan. Flood control projects continued throughout the watersheds, but dam building ceased. Exactly why is uncertain.

No mention of the Bolton dam appears in the 1973 council minutes of either the former Albion Township or the former village of Bolton. (It was their final year as municipal governments prior to regionalization.) Nor do the minutes of the new Region of Peel in 1974 offer specifics on cancellation. Even the available information at the TRCA does not reveal a motion to cancel the dam.

The generally accepted theory is that impetus for dam construction on the Humber and elsewhere faded at the same time the authority found it had expended most of its budget on land acquisition to prepare for them. According to Ken Higgs, MTRCA’s then secretary/treasurer, by the mid ’70s the plan to build dams “just died.” In Bolton and all along the Humber River valley, no one mourned.

More Info

Are earth dams scary?

Each of the dams proposed by Metropolitan Toronto and Region Conservation Authority in 1961 was a variation of an earth dam. Put simply, an earth dam has concrete gates or spillways at its head with sides mounded with a combination of natural materials such as earth and rocks. Although some earth dams around the world have indeed failed, the design continues to be used extensively. What worried residents of Bolton and Albion was that the dam site had a long-established reputation for unstable subsoil with much evidence of soft sand and quicksand. In 1973, when the 30-metre dam was officially proposed, no structure that big had ever been built in or near the town, let alone one supposed to hold back a 7-kilometre-long lake.

Not just floods: the Humber’s other story

In 1999 the Humber River was designated a Canadian Heritage River, not the first to be so honoured (it’s the 26th) and not the first urban river to be recognized. That position belongs to the Grand River. But the Humber is the most urban of Canada’s designated rivers, with almost half its watershed flowing through developed lands. The 600 lakes and ponds and 750 tributaries (and 33 bridges) in the 903-square-kilometre watershed are embraced by 12 municipalities, one of them the largest in the country. It’s the only heritage river that can be reached by subway!

It is also a river of history, containing evidence of 10,000 years of human settlement. Native peoples once made the river part of the Carrying Place Trail connecting Lake Ontario to the upper Great Lakes, and newcomers to Canada built some 164 mills on its banks in the early days of settlement.

Perhaps the most notable development in the Humber’s long history is also the most recent. Where a reservoir lake was once destined to fill the valley north of Bolton, the Humber Valley Heritage Trail now provides a chance to get up close and personal with the river. Even the river must be grateful for that.

Related Stories

The Grand River – When Your Neighbour is a River

Jun 20, 2016 | | Historic HillsNot only does the Grand River lay out nature’s beauty, it also offers opportunities for recreation, commerce and development. Yet all this comes at a cost, for the Grand can be both friend and foe.

Big Weather

Jun 18, 2009 | | EnvironmentHold on to your hats! The weather, she-is-a-changing. Global warming is exacerbating Canada’s gloriously variable weather, adding a growing current of concern to our favourite topic of conversation. It’s been more than two decades since the “big tornado” hit these hills in 1985, but in recent years the incidence of smaller tornadoes, high winds and violent storms has escalated.

Wow! And here we are in 2019 and Bolton is still getting flooded out with Humber River ice breakup.

Greg Whilsmith from Long Branch, Etobicoke (ex- Heart Lakers, often travelling through Bolton) on Mar 17, 2019 at 12:13 pm |