Behind the Scenes at Museum of Dufferin

What makes your old family heirlooms or bric-a-brac museum-worthy? It’s all in the story they tell.

Ballpoint pens, dangling shoulder bags, inattentive oafs – all are the bane of archivists and curators. This is particularly so in the cool and windowless storage rooms beneath the recently renovated exhibition hall of the “reimagined” Museum of Dufferin.

Carelessly wielded pens, it seems, can permanently damage delicate documents that should be marked, judiciously, only by professionals with archival-quality pencils. And on every shelf of every aisle of the mechanized rolling storage units of the MoD sits a meticulously catalogued hodgepodge of artifacts, once personal treasures, practically asking to be accidentally swept to the floor with an embarrassing crash.

What makes each item so special? Its story.

Collecting, cataloguing, displaying and sharing artifacts that tell the stories of Dufferin County has been the mandate of the Museum of Dufferin since it opened as the Dufferin County Museum and Archives in 1994.

Housing a collection of 50,000 objects and welcoming more than 10,000 visitors annually, the MoD’s spacious main building is rich in character. The “big green barn,” as some fondly call the oversized structure, perches against the rolling countryside at Airport Road and Highway 89, where Mulmur Township and the town of Mono kiss.

The collection comprises mostly donations from members of the public, who are usually encouraged to make an appointment to visit the museum to discuss their offerings with archive staff. But this past summer, while the museum was closed for much-needed renovations, staff expanded their established Archivist on the Road program and publicized specific days when the public was invited to local libraries to drop in and discuss donating their treasured objects, photographs or documents to the museum.

And drop in they did. “Very cool” was a common assessment by MoD archivist Laura Camilleri as she examined items people had brought in. In Grand Valley, for example, Camilleri had high hopes for a “cool” 1904 Dominion Daily Farm Journal, a smallish, yellowed journal spotted with entries written in a faded, spidery scrawl.

In an age before Instagram and tweeting, keeping diaries and farm journals was entertainment. “That’ll be my afternoon,” said Camilleri, fingers already clacking at her laptop as she typed in family names and election results mentioned in the journal, seeking connections to existing Dufferin County records (birth, death and wedding announcements, and newspaper articles) from long ago.

Is the journal important? “I don’t know yet,” she said. “We have a lot of stuff. We don’t have a lot of stories, detailed historical information. Historical details make a journal interesting.”

And interesting this particular journal proved to be. But not for Dufferin County. “It told the story of someone’s life,” Camilleri said later. “Just turned out that that someone lived in Wiarton.” The journal was sent on to its rightful home at the Bruce County Museum and Cultural Centre.

But the bunkhouse was a different story. Hand-delivered during the donation day at the Orangeville library, this artifact is an exquisitely handcrafted, HO-scale model of the railway workers’ bunkhouse that stood next to the Orangeville train station when it was located on the Townline. (HO, pronounced aitch-oh, refers to a popular scale – 1:87 – used by railway modelling enthusiasts.) Unfortunately the bunkhouse was destroyed by fire in 2006.

Curator Sarah Robinson (left) and archivist Laura Camilleri between the rolling shelves that house historic documents in the Museum of Dufferin. Laura and Sarah encourage people to talk to them about possible museum donations. “It’s the stories that help us decide what’s vital,” says Sarah. Photo by Pete Paterson.

About a foot square and nine inches tall, the bunkhouse model features a roof of simulated grey shingles over walls of hand-painted burgundy brick cut with delicate, butterscotch-coloured windows and frames. With the maker’s signature on the bottom, it was part of a much bigger collection created by Steve Revell of Erin. A Credit Valley Railway buff and model hobbyist, Revell died in 2013, so the bunkhouse was brought in by a family member.

Curator Sarah Robinson, who began at the MoD as a summer intern, rated the bunkhouse model exceptional. “We’re not just getting a piece,” said Robinson. “We’re getting the history, getting memories [of Revell], his work processes, all the background photos. Very specific. Very local.”

Both Robinson’s office and the warren of MoD storage rooms separated by heavy fire doors are kept at 18 to 25 C. Sweaters come with the territory for the MoD’s 11 staff and many volunteers.

In the usually dark and closed-to-the-public archival storage room, noted Camilleri, 30 to 35 per cent humidity is paper’s “happy place.” Large-item storage holds tubas, gas pumps, wooden fairground horses, pulpits galore, sleighs, wagons, taxidermy and road signs, including the familiar crown-topped Highway 9 signs that once bore the words “King’s Highway.”

Small-item storage is a hoarder’s heaven: shelf upon shelf of old sporting equipment, crockery, fair ribbons, commercial-branded trinkets, pennants, hats, wedding dresses and military uniforms. All with stories. Local stories.

For a time, the model bunkhouse and its story sat in Robinson’s office with a TCR (temporary custody receipt), which placed the artifact in the museum’s possession but not yet under its ownership. “A donation is yours until it’s ours,” explained Robinson. Donors must sign a deed of gift, which legally transfers ownership to the museum. Once this was done with the bunkhouse, it was photographed, documented, researched, assigned a specific identification number and added to the collection.

But being added to the collection doesn’t generally mean an item is immediately or permanently put on display. With respect to any museum or archive, think iceberg. Perhaps 10 per cent of any collection is on public view at a given time.

“People usually understand once we explain we rotate the collection,” said Robinson, adding that treasures always have a safe home and are carefully cared for. The level of care offered at the MoD may be preferable to throwing something into a trunk or pushing it to the back of your closet. “And we are starting to put the collection online, so artifacts will always be available for people to research and appreciate, in a different way.” For those who want to check out an item firsthand, objects are available to be examined, if the museum is given a little notice.

On a kiddy’s wagon in the nook by the elevators, on a day MoD is closed, sits a small, dark and somewhat forlorn-looking wooden trunk, sturdily wrapped in metal bands. It is a recent donation waiting to join the MoD collection.

A seemingly empty trunk. But the story it holds, as well as the story it will tell, makes it significant.

The trunk, with the number 6032 deeply branded into its thick leather handles, once held the meagre worldly possessions of Ada Lamb Stinson (born Ada Lamb), a “Barnardo child” who was settled in Shelburne.

Thomas Barnardo was a preacher who founded homes for destitute children throughout England in the last half of the 19th century. Between 1870 and 1939, about 35,000 Barnardo children were among roughly 100,000 British “home children” shipped to Canada to be placed in foster homes. The lucky ones, such as Ada, were adopted into loving families. Those less fortunate were treated like indentured servants and used – and sometimes abused – as farm workers or domestics. An empty trunk – with echoes.

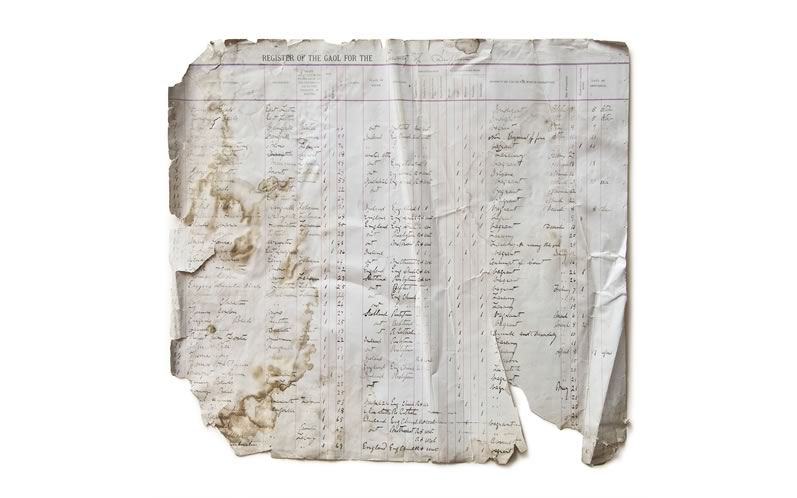

Paper speaks, too. At her heavy 1930s-era Eaton’s catalogue desk, Camilleri leafs through reproductions of tattered blue ledger pages from the Gaol Registry of Dufferin County, 1 October 1890–30 September 1891. The original, “incredibly unstable” ledger, is carefully preserved in storage.

Jail records of the day detailed every inmate’s name, residence, occupation, sex, religion, marital status, literacy level, crime, sentence and number of previous incarcerations.

Though 31-year-old Luther resident Henry Beals is listed as single early in 1890, with no fixed occupation or stated religion, perhaps he became someone’s great-great-grandfather. Relations who might be interested can see, on page 5, line 48, that Henry, who could both read and write, was doing a six-month stretch for vagrancy and that the Dufferin County Gaol was his second home, this being his 15th incarceration. All this information is laboriously indexed in the MoD’s digital archives and can be summoned and cross-referenced in an instant. (For more on the jail, see Historic Hills)

The roles of curator (3D objects) and archivist (documents) dovetail and overlap, but Camilleri usually does the research, Robinson the display. Does this mean one gets the grind, the other the glory? Camilleri laughed out loud. “It doesn’t work like that. Things on display have context. Without context, it is what it is. We both tell its story. Together, we create every part of the museum.”

Camilleri was particularly excited to learn what was on the back of the bunkhouse. The MoD’s collection includes photos of the building, with workers and railway patrons posing stiffly out front. But the rear side had remained a mystery. Until the donation.

But really, who cares? “There is always someone who cares,” Camilleri responded. “Model builders, miniature fanciers, train buffs … I care.” But, some might ask, why should precious public funds go to satisfy that curiosity instead of being turned to mending bridges and filling potholes?

The answer came tag team and firmly. Robinson: “Look how fast Orangeville is changing. We need to hold on to what we once had as much as we need to embrace change.” Camilleri: “If all you are going to do is put money toward roads and bridges, all you are going to have is roads and bridges. Think about the rest.”

Although the MoD’s summer donation days were considered a success, donations to the collection are appreciated at any time – and no hard sell is involved. “Photographs are the most sensitive,” noted Camilleri. “They are people’s memories. As people get older they might be the only memory left of that time and place. I tell them I’d rather wait. Come back when you’re ready. Or will them to us!”

“There is always a discussion,” added Robinson. “Donors are going to understand that we respect their object, do research on it, learn the history, the many sides necessary to correctly identify, display and preserve it.”

Robinson concluded by summing up the crucial role played by story in shaping the museum’s acquisitions. “A hat is a hat is a hat,” she said. “We look for the story it tells, because an object’s significance is wrapped up in its story. We encourage people to tell those stories. It’s the stories that help us decide what’s vital for the Museum of Dufferin collection.”

Recent donations to the Museum of Dufferin

A trunk that once held the worldly possessions of Barnardo child Ada Lamb. Photo by Pete Paterson.

HO-scale model of Orangeville’s old train station and bunkhouse, created by Steve Revell of Erin. Photo by Pete Paterson.

Related Stories

Dufferin County’s Jail

Nov 20, 2018 | | Historic HillsWith the notable exception of inmates charged with vagrancy (more on this later), the vast majority of time served at Dufferin County Jail was measured in days, weeks or a few months.

Illuminating the Past: Personal History

Nov 20, 2018 | | ArtsHow private archivist Alison Hird’s work is helping one family reflect on their personal history – and preserve it for the future.